Gastric Cancer

Original Editors -Nick Goulooze & Corey Malone from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

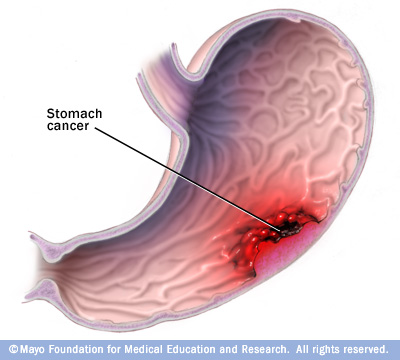

Gastric cancer (also known as stomach cancer) is characterized by rapid or abnormal cell growth within the lining of the stomach, forming a tumor.[1]

Prevalence

[edit | edit source]

Estimated new cases and deaths from stomach cancer in the United States in 2012:[3]

New cases: 21,320

Deaths: 10,540

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

[edit | edit source]

| Localized |

25% |

| Regional |

31% |

| Distant Metastatic |

32% |

| Unstaged | 12% |

- Signs and symptoms tend to arise later in the disease process, time frame is variable.

- Subjective presentations: Indigestion, bloating, nausea, heartburn, blood in stool, unexplained weight loss, vomiting, difficulty swallowing

- Objective gatherings: Enlarged stomach, swollen lymph nodes, palpable mass, skin conditions, jaundice[4][5]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- A Study conducted by Heemskerk et al investigated associated co-morbidities upon history intake of 235 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer between 1992-2004.

- 138 of the 235 patient had at least one co-morbidity

| Co-morbidity | No. of Patients | % |

| Cardiovascular | 87 | 37 |

| Pulmonary | 24 | 10 |

| Diabetes | 19 | 8 |

| Other carcinoma | 20 | 9 |

| Previous GI surgery | 18 | 8 |

| BMI > 30 | 12 | 5 |

| Clotting disorder | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 11 | 5 |

Medications[edit | edit source]

There are many medications that are used for gastric cancer, each one prescribed by the patient's physician. Before a specific medication is prescribed to the patient, the physician should go through an extensive overview of the history of the patient, looking for history of allergic reactions to certain drugs. The patient should also be warned of adverse side effects that could effect the patients everyday activities.

Doxorubicin Hydrochloride

Doxorubicin Hydrochloride is used in conjunction with a number of other medications in order to treat a number of cancers including gastric cancer. It is in the class of drugs called anthracyclines, and it works by stopping or slowing the growth of cancer cells in a person's body.[7]

Drugs Approved for Stomach (Gastric) Cancer

This page lists cancer drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for stomach (gastric) cancer. The list includes generic names and brand names. The drug names link to NCI's Cancer Drug Information summaries. There may be drugs used in stomach (gastric) cancer that are not listed here.

Adriamycin PFS (Doxorubicin Hydrochloride)

Adriamycin RDF (Doxorubicin Hydrochloride)

Adrucil (Fluorouracil)

Docetaxel

Doxorubicin Hydrochloride

Efudex (Fluorouracil)

Fluoroplex (Fluorouracil)

Fluorouracil

Herceptin (Trastuzumab)

Mitomycin C

Mitozytrex (Mitomycin C)

Mutamycin (Mitomycin C)

Taxotere (Docetaxel)

Trastuzumab

http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/stomachcancer

Targeted drugs

Targeted therapy uses drugs that attack specific abnormalities within cancer cells. Targeted drugs are used to treat a rare form of stomach cancer called gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Targeted drugs used to treat this cancer include imatinib (Gleevec) and sunitinib (Sutent).

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=treatments-and-drugs

Xeloda

http://www.drugs.com/condition/stomach-cancer.html

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

All of these tests are done in order to either to diagnose for gastric cancer or to determine what stage the cancer is in, in order to determine the best treatment approach for that patient. Following are a number of diagnostic and special tests.

Endoscopy[8]

This is a diagnostic procedure involving a thin tube with a camera inside of it that is passed through you esophagus into your stomach. This allows your doctor to find any suspicious tissue within your stomach that should be tested for cancer. If your doctor decides to send stomach tissue off to a lab to check for cancer, this is called a biopsy in which test can be done to determine if the suspicious tissue is malignant or benign.

Imaging[8]

-CT scan

-PET

-MRI

Exploratory Surgery[8]

This is performed should the doctor suspect your cancer has spread beyond just the stomach tissue. This procedure is done laparoscopically

Physical Exam[10]

The doctor may check for enlarged lymph nodes, an enlarged liver, increased fluid in the abdomen (ascites), or abdominal lumps felt during a rectal exam.

Upper GI Series[10]

These are X-rays of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the intestine taken after you drink a barium solution. The barium outlines the stomach on the X-ray, which helps the doctor, using special imaging equipment, to find tumors or other abnormal areas

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

Doctors aren't sure what causes stomach cancer. There is a strong correlation between a diet high in smoked, salted and pickled foods and stomach cancer. As the use of refrigeration for preserving foods has increased around the world, the rates of stomach cancer have declined.

In general, cancer begins when an error (mutation) occurs in a cell's DNA. The mutation causes the cell to grow and divide at a rapid rate and to continue living when normal cells would die. The accumulating cancerous cells form a tumor that can invade nearby structures. And cancer cells can break off from the tumor to spread throughout the body.

Types of stomach cancer

The cells that form the tumor determine the type of stomach cancer. The type of cells in your stomach cancer helps determine your treatment options. Types of stomach cancer include:

Cancer that begins in the glandular cells (adenocarcinoma). The glandular cells that line the inside of the stomach secrete a protective layer of mucus to shield the lining of the stomach from the acidic digestive juices. Adenocarcinoma accounts for the great majority of all stomach cancers.

Cancer that begins in immune system cells (lymphoma). The walls of the stomach contain a small number of immune system cells that can develop cancer. Lymphoma in the stomach is rare.

Cancer that begins in hormone-producing cells (carcinoid cancer). Hormone-producing cells can develop carcinoid cancer. Carcinoid cancer in the stomach is rare.

Cancer that begins in nervous system tissues. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) begins in specific nervous system cells found in your stomach. GIST is a rare form of stomach cancer.

Because the other types of stomach cancer are rare, when people use the term "stomach cancer" they generally are referring to adenocarcinoma.

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=causes

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Surgical management of gastric cancer

Simon Msika, Grégoire Deroide, and Reza Kianmanesh.

Louis Mourier University Hospital - Colombes (University Paris 7), Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Colombes Cedex, France

Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for gastric cancer (GC). Although declining in incidence in western countries during the last twenty years, it remains an important cancer problem (1). In France, it still occurs with an incidence rate of 13.8 per 100,000 inhabitants per year (Côte d'Or, Burgundy, France, Digestive Tract Cancer Registry 1983–1987) (2). In 1990, GC was the second most frequent cancer in the world (1), the 6th cancer among men in France and the third of all digestive cancers, after colorectal and oesophagal cancer. In France, the number of estimated new cases is about 8700 per year.

Prognosis of GC is poor. The 5 year survival rate does not rise over 20%, especially in population-based series (3), far closer to reality than those coming from hospital series. Surgery with curative intent remains the only way to improve survival. However, results in the treatment of GC are globally disappointing and results of population-based series (4–7) concerning improvement of 5 year and 10 year relative survival rate in overall patients and after curative surgery are controversial. The major component of the overall improvement was a decreasing of operative mortality (3, 8). Poor results in survival may be explained by the fact that when symptoms occur, the cancer has often already spread and so far only a few percentage of patients are eligible for curative surgery.

As in the literature, many published studies about surgical treatment of gastric cancer are found, this paper has the main objective to make a synthesis on the evidence based in the treatment of gastric cancer and point out the guidelines and pathways of research in the future.

Special points will be discussed:

a.

the limits of gastric resection,

b.

the extension of the lymph node dissection, and

c.

the value of adjuvant therapy to surgery.

Go to:

Surgical treatment

Actually, surgery is the only reliable possibility of a curative treatment. The aim of surgery is to remove as completely as possible all grossly visible tumor tissue and to obtain histologically free surgical margins. This goal (R0 resection (9)) is usually reached in 45% of cases of diagnosed GC in population-based series (3) and up to 55–60% of cases in specialized centers (10).

During the operative procedure, gastric resection depends on cancer spread, i.e. tumoral infiltration through the gastric wall, tumoral extension to adjacent organs, and lymph node involvement.

Limits of gastric resection

The extension of gastric resection depends on the location of the tumor (according to ICD-O classification (9)).

Cancer located to the body or the corpus of the stomach (C-16.2) requires total gastrectomy. Reconstruction of digestive continuity is then realized by a Roux-en-Y oesojejunostomy. Pouch and Roux-en-Y reconstruction seem to improve postoperative quality of life after total gastrectomy (11).

Cancer of the antrum (distal third and pylorus: C-16.3 and 16.4), may be managed by sub-total distal gastrectomy. Reconstruction is realized by a method similar to Bilroth I or II procedures. Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy has been proposed to avoid bile-reflux in the gastric remnant (12), but vagotomy is mandatory to prevent anastomotic peptic ulcer, depending on the size of the gastric remnant. This type of reconstruction called total duodenal diversion has been proposed in patients with severe gastrooesophageal reflux disease (12); however, it can be indicated for GC after distal gastrectomy, in cases of patients with a hope of long term survival as early gastric cancer (EGC) for example. For a long time, routine radical total gastrectomy was proposed for distal lesions by general authors (13, 14), particularly from Japan (15); it rationale was based on the effect that survival was better after an extensive lymphadenectomy, including pancreatic tail resection; in these conditions, total gastric resection was necessary. Actually, routine total gastrectomy is no more the only recommended treatment for distal lesions as it was demonstrated in a French prospective multicentric controlled study (16). In this study (16), there was no significant difference on the 5-year survival rate between total or subtotal distal gastrectomy for distal lesions. However, one important point was the fact that after subtotal distal gastrectomy, free margins of resection should not be less than 5–6 cm on the stomach and no less than 2 cm on the proximal duodenum.

Cancer of the cardia needs a particular approach. In fact, they are consider as a different clinical entity (17), while others (18) assimilate them to a lower oesophageal cancer whatever histological differences. As a matter of fact, the limits of the resection depends on the oesophageal extension itself. Despite a lack of controlled study, there is a tendency to achieve total gastrectomy for lesions limited to the cardia and proximal oesophago-gastrectomy by abdominal and right thoracic combined approach (Lewis-Santy procedure) for lesions extended to the lower oesophagus (19).

Borrmann type 4 infiltrative GC, whatever their topography (partial or total), are usually treated by total gastrectomy because of a frequent wide extension through the gastric wall (20). The relative incidence of this type of cancer is increasing with time (21, 22, 23), and wider resection to surrounding organs including extended lymphadenectomy, as proposed by Japanese authors (24), does not seem to improve prognosis for all of the TNM stages, except probably in stage III (25), but no controlled trials has been performed in Borrmann type 4 GC.

At last, EGC, whatever its location, requires similar treatment as for other types because of the possibility of wide submucosal extension and lymph-node involvement. Some Japanese authors suggested limited resections (26) for EGC, but these procedures are not currently diffused in Europe.

Lymph-node dissection

Lymph node extension is the most prognostic feature in GC. Therefore the crucial question of the last twenty years was related to the prognostic impact of lymph node dissection. Many studies have been realized successively: retrospective, prospective and finally controlled prospective studies. During the last ten years, four prospective controlled studies (27–30) compared the type of lymph-node dissection limited (D1) versus extended (D2), in the surgical treatment of GC. The two last controlled studies gave firstly only results about mortality and morbidity of the D1 and D2 procedures (29, 30), then secondly results about long term survival (31, 32).

Actually, until now, none of these randomized trials has demonstrated the superiority of D2 versus D1 specially in term of 5-year survival (no superiority after D2 dissection); furthermore, they showed an increased incidence of postoperative complications rate after D2 vs. D1 dissection. Highest rates of morbidity and mortality are partly due to anastomotic leakage and consequences of the pancreatic tail resection during D2 dissection. These findings led some authors (32) to conclude that D2 resection without pancreatico-splenectomy, excluding the negative effect on operative mortality, may be a good approach for the lymph-node dissection of GC rather than standard D1.

The debate seemed to be definitively closed, but a recent multicentric prospective non controlled study (10) pointed out a significant improvement of 10-year survival rate in TNM stage II cancer after D2 dissection (defined in this study as an extended lymph-node dissection with more than 25 removed nodes). Although this study was multicentric, involving many surgeons, standardization of lymph-node dissection was set and routinely realized after several meetings, as well as the last controlled trials (31, 32). In addition to these results, extended lymph-node dissection did not increase mortality and morbidity rates.

In France, standardized extended lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer is not routinely performed by all the surgical teams, and systematic count of lymph-nodes in the specimen, as proposed in most of actual trials specially by Japanese authors, but also by western ones, is not standardized for all western pathologists. In the near future, the standardized techniques of lymph-node dissection and pathological analysis might be needed for oncological accreditation.

As morbidity and mortality are correlated to resection of the spleen and pancreatic tail in controlled studies, the German study (10) suggests that D2 resection should be associated to subtotal distal gastrectomy in stage II and IIIA to prevent the necessity of a resection of the spleen and pancreatic tail.

When a total gastrectomy is performed in curative intent, intermediate “1.5” lymph-node dissection between D1 and D2 could be realized, including splenic lymph-node dissection without splenectomy as it was suggested by a Japanese author (33).

Despite the effect of lymph-node dissection on survival has not been proved, it is worth to standardize and familiarize European teams, to precise staging and margin clearance.

Palliative surgical treatment

The best palliation in GC whenever possible is still surgical resection. In fact, morbidity and mortality of palliative surgery without resection (laparotomy alone or by-pass procedures) is extremely high and should be avoided. Perhaps a better pre-operative evaluation by CT scan (heliscan) and/or laparoscopic staging indicated in selected patients could decrease the number of explanatory laparotomy in unresectable GC (34).

Although, 25% of the patients with diagnosed GC can benefit from palliative procedures (3). There are two different types of the palliative treatment of GC: resection of the tumor and surgical by-pass procedures without resection. Actual pre-operative investigations can not always predict the type of operative procedure as exactly as during operative exploration. Laparoscopic staging could be indicated in these conditions (34).

Mostly, in many cases, the possibility of tumoral resection appears to surgeons as a perioperative finding, and per-operative manual exploration may find hepatic metastasis, wide or localized peritoneal implants. in these conditions, palliative surgery depends on local anatomy and preoperative clinical symptoms. A bleeding tumor is more to be resected than an obstructive one for which a by-pass might be recommended. In a general manner, oncologic rules of resections must respect the followings: little free margin on surrounding organs, inutility of lymph node dissections, unless it is required to obtain a free margin. There is a lower mortality and morbidity in palliative resections rather than in by-pass without resections. However, by-pass procedures can still be indicated when resection risk appears to be too high (morbidity and mortality) and/or in case of biliary and/or digestive obstruction. Then, a gastroenterostomy and/or a biliary diversion may be realized.

Non operative treatment

Non surgical treatment represents 30% of diagnosed GC (3) and is indicated in case of diffuse hepatic, peritoneal and/or extra-abdominal metastasis without obstructive symptoms, sub-clavicular lymph nodes and/or the presence of severe physiological disorders and/or undernutrition. Treatment in these cases is difficult and varies from abstention to endoscopic desobstruction (endoscopic laser therapy, argon beam, heater probe coagulation therapy, endoscopic stent). Chemotherapy can be indicated only in phase II protocols.

Go to:

Non surgical treatment

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant and neo adjuvant

There is a high risk of peritoneal and/or hepatic recurrence in GC. It depends on perioperative staging. This feature has led naturally to a plethora of adjuvant chemotherapy series. Drugs usually employed are 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), mitomycin-C, cisplatin, adriamycin, and methyl-CCNU. Many authors report poor and disappointing results in the survival rates and the oldest trials demonstrating improvement with adjuvant chemotherapy (35, 36) were not confirmed by a recent prospective controlled study from the French Associations for Surgical Research (37). This study (37) did not demonstrate any improvement in survival by the administration after curative surgery of an association of cisplatin and 5-FU versus no treatment. A meta-analysis (38) came to the same conclusions. Improvement may come from new associations of drugs, reduction of toxicity and better observance of treatments. Actually, new protocols of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy have been proposed and are in process.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with or without hyperthermia

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is a logical alternative to the systemic way, as peritoneal diffusion and seeding is important. It is related to be easier to deliver chemotherapy with a higher intracellular concentration. Until now, there were 5 controlled trials (39–43) about intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPC), essentially as a preventive therapy. All came from Japanese surgical teams except the last one which was performed in collaboration with the Washington Cancer Institute (43). This trial compared a particular type of chemotherapy, early post operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC), developed by Sugarbaker in the treatment of carcinomatosis. There was no hyperthermia in this trial and the treatment started the day after the operative procedure using the drain catheter in place. This study included a great number of patients: 248 were divided into two groups of 125 and 123 respectively: surgery vs. EPIC + surgery all stage together. There was no significant difference in the 5-year survival rate but a little advantage to EPIC was observed (38.7% vs. 29.3%). In the stage III patients, there was a significant superiority of EPIC (49.1% vs. 18.4%; p = 0.011).

Special attention to these techniques is needed because of high morbidity and mortality rates. Complication rate due to EPIC is approximatively 37.7%, including prolonged ileus, leucopenia and pain. High incidence rate of post-operative hemoperitoneum and intra abdominal sepsis without anastomosis fistula was observed. Post operative mortality was higher but not significantly: 6.4% in the EPIC group vs. 1.6% in the control group. Authors concluded that this procedure could be interesting in the prevention of carcinomatosis, but in selected patients.

The problem of morbidity can be resolved with time as long as the learning curve progresses. It is certainly a new way of research and it might improve prognosis.

Radiotherapy

Its efficacy has not been demonstrated; there are few trials on the subject and most associate radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Per operative radiotherapy still constitute an interesting way of research as a non significant tendency was observed.

Immunotherapy

Several Japanese reviews have studied the effect of immune stimulators as adjuvant therapy to curative gastric cancer surgery. There was a small number of randomized trials and all compared standard chemotherapy program with and without the immune stimulator protein-bound polysaccharide (PSK). In one report (44), the PSK group had both an improved 5-year disease free survival and overall 5-year survival. However, no Western trials have confirmed these results.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6969/

Pain medications & modalities

Your pain management clinician may recommend anti-inflammatory medications, opioid medications or non-opioid medications to help control your pain. These pain medications may be taken orally or delivered using the following administration methods:

Intravenous

Implanted pain pumps

Peripheral

Epidural

Rectal

Topically

Medicated patches

Nerve blocks for stomach cancer pain

There are two nerve block therapies commonly used for stomach cancer pain management:

Celiac Plexus Block – This procedure aims to reduce chronic pain in the upper abdomen. It blocks the sensation of pain in the bundle of nerves in and around the stomach, liver, pancreas, gallbladder, kidneys and bowel.

Hypogastric Plexus Block – This block affects nerves in the lower abdomen, near the upper front of the pelvis. It can prevent pain in the bladder and lower bowel. For men, it also reduces pain in the testicles, penis and prostate; for women, it minimizes pain in the uterus, ovaries and vagina.

For either of these procedures, an anesthesiologist first must inject a temporary, local anesthetic into the area where the affected nerves are to determine if you experience pain relief. If the temporary block works, the anesthesiologist will administer a neurolytic solution (i.e., pain killing medication) to the same area 24 hours later. This long-term nerve block will destroy the nerves, thereby preventing you from feeling pain in that region of the abdomen.

Stomach cancer patients may experience pain relief from a celiac plexus block or hypogastric plexus block for an extended period, which may last days, weeks or months (depending on your response to the nerve block).

http://www.cancercenter.com/stomach-cancer/pain-management.cfm

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

-Lymph therapy

-Exercises during chemo treatment to prevent atrophy of musculoskeletal system due to side effects of treament

-PT post cancer to restore loss of function that may have occured during medical management of cancer

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnoses[11]

Esophageal Cancer

Esophageal Stricture

Esophagitis

Gastric Ulcers

Gastritis, Acute

Gastritis, Atrophic

Gastritis, Chronic

Gastroenteritis, Bacterial

Gastroenteritis, Viral

Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin

Malignant Neoplasms of the Small Intestine

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278744-differential

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1NGmwZeh8JwVIzrKgHG1LrDm0izTr7ViJiDkSYAY2BW5hiXsx0|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ The Free Dictionary. Stomach Cancer. http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/stomach+cancer (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ http://www.riversideonline.com/source/images/image_popup/c7_stomach_cancer.jpg

- ↑ National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Stomach (Gastric) Cancer. http://cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/stomach (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ Medscape. Gastric Cancer Clinical Presentation. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278744-clinical#a0217 (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. General Information About Gastric Cancer. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/gastric/Patient/page1 (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ Vincent H., Fanneke L., Karel H., Anton H. Gastric carcinoma: review of the results of treatment in a community teaching hospital. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2007; 5:81

- ↑ MedlinePlus. Doxorubicin. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a682221.html (accessed Feb 12 2013)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mayo Clinic. Stomach Cancer Tests and Diagnosis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stomach-cancer/DS00301/DSECTION=tests-and-diagnosis (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ http://www.newcastlesurgery.com.au.php53-22.ord1-1.websitetestlink.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/gastroscopy.gif

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 WebMD. How is Stomach Cancer Diagnosed. http://www.webmd.com/cancer/stomach-gastric-cancer?page=2 (accessed 2 Feb 2013)

- ↑ Medscape. Gastric Cancer Differential Diagnoses. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/278744-differential (Accessed 2/13/13)