Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mohit Chand (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Yves Demol|Yves Demol]], [[User:Aurelie Ackerman|Aurelie Ackerman]] | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Yves Demol|Yves Demol]], [[User:Aurelie Ackerman|Aurelie Ackerman]] | ||

''' | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== < | == Definition/Description == | ||

[[File:Iliotibial tract - Kenhub.png|alt=Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view|right|frameless|500x500px|Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view]] | |||

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common knee condition that usually presents with pain and/or tenderness on palpation of the lateral aspect of the [[knee]], superior to the joint line and inferior to the lateral femoral epicondyle.<ref name="p1">Lavine R. Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2010; 3(1-4) :18–22</ref>. It is considered a non-traumatic overuse injury, often seen in runners, and is often concomitant with underlying weakness of hip abductor muscles.<ref name="p3">Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of Anatomy, 2006; 208(3): 309-316</ref> <ref name="p2">Michael D. Clinical Testing for Extra-Articular Lateral Knee Pain: A Modification and Combination of Traditional Tests. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 2008; 3: 107–109.</ref>. The current theory is that this condition is likely to be caused by compression of the innervated local adipose tissue<ref name=":0">Lazenby, T & Geisler, P (2017). Iliotibial Band Impingement Syndrome: An Updated Evidence-Informed Clinical Paradigm. Published 2017/03/06 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22882.53448</ref>.Studies have described an ‘impingement zone’ occurring at, or slightly below, 30° of knee flexion during foot strike and the early stance phase of running. During this impingement period in the running cycle, eccentric contraction of the tensor fascia latae muscle and of the gluteus maximus causes the leg to decelerate, generating tension (compression) in the iliotibial band.<ref name="Van der worp Maarten et al.">van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 2012; 42(11):969-92</ref> | |||

Image: Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view<ref >Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view image - © Kenhub https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/iliotibial-band</ref> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

[[Image:Itbs.png|frame|right|<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. </span>[http://sequencewiz.org/2014/05/28/it-band-stretching-it-band-rolling-it-band-tightness/ Figure [1]<span style="line-height: 1.5em;"><nowiki>]</nowiki></span>]] | |||

The iliotibial tract is a thick band of fascia that runs on the lateral side of the thigh from the iliac crest and inserts at the knee.<ref name="Robert L. Baker et al." /> It is composed of dense fibrous connective tissue that appears from the [[Tensor Fascia Lata|m. tensor fasciae latae]] and [[Gluteus Maximus|m. gluteus maximus]]. It descends along the lateral aspect of the thigh, between the layers of the superficial fascia, and inserts onto the lateral tibial plateau at a projection known as Gerdy’s tubercle<ref name="p3" />. In its distal portion the iliotibial tract covers the lateral femoral epicondyle and gives an expansion to the lateral border of the [[Patella|patella]]. While the iliotibial band does not have any boney attachments as it courses between the Gerdy tubercle and the lateral femoral epicondyle, this absence of attachment allows it to move anteriorly and posteriorly with knee flexion and extension. | |||

Histologic and dissection study of the iliotibial band <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">at the lateral femoral epicondyle and gluteus maximus and fascia latae suggest a </span><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">mechanosensory role acting proximally on the anterolateral knee</span><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. </span>[http://sequencewiz.org/2014/05/28/it-band-stretching-it-band-rolling-it-band-tightness/ Figure [1]<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">]</span> This mechanosensory role may affect the interpretation of the ligament versus tendon function of the ITB from [[Hip Anatomy|hip]] to lateral femoral epicondyle. | |||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | |||

< | ITBS is one of the most common injuries in runners presenting with lateral knee pain, with an incidence estimated to between 5% and 14%. <ref name="Van Der Worp Maarten et al." /> Further studies indicate ITBS is responsible for approximately 22% of all lower extremity injuries.<ref name="p1" /> | ||

ITBS is a common cause of knee pain laterally, especially in athletes for sports involving repeated knee flexion and extension, such as cyclists and runners<ref>Aderem, J., 2015. The biomechanical risk factors associated with preventing and managing iliotibial band syndrome in runners: [https://arthroscopysportsmedicineandrehabilitation.org/article/S2666-061X(20)30024-9/fulltext a systematic review.]</ref>. Recent evidence suggests ITB contributes to rotational knee stability as well, and therefore, pivoting sports might increase the risk for ITBS<ref>Godin JA, Chahla J, Moatshe G, Kruckeberg BM, Muckenhirn KJ, Vap AR, Geeslin AG, LaPrade RF. A comprehensive reanalysis of the distal iliotibial band: quantitative anatomy, radiographic markers, and biomechanical properties. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0363546517707961 2017 Sep;45(11):2595-603.]</ref>. | |||

[ | The ITBS disease process is multifactorial, and various mechanisms have been suggested for it: repeated rubbing of the iliotibial band on the lateral femoral epicondyle during knee flexion and extension; iliotibial band impingement at 30° knee flexion; weakness of hip abductors resulting in iliotibial band overtightening during knee flexion–extension; lateral synovial recess or sub-iliotibial band bursa of the lateral knee inflammation; lateral epicondyle periosteal inflammation; and others<ref name=":1">Bolia IK, Gammons P, Scholten DJ, Weber AE, Waterman BR. Operative Versus Nonoperative Management of Distal Iliotibial Band Syndrome—Where Do We Stand? A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation. [https://arthroscopysportsmedicineandrehabilitation.org/article/S2666-061X(20)30024-9/fulltext 2020;2(4):e399–e415.] </ref>. | ||

== Risk factors == | |||

Due to the difference in male and female anatomy, risk factors have been considered separately for each group. | |||

A systematic review suggests associations between ITBS and peak hip adduction angle, peak hip internal rotation angle, peak knee internal rotation angle, and isometric hip abductor strength in female runners. Female runners with current ITBS have less hip internal rotation during stance phase of running compared to healthy controls. However, peak hip adduction angle had no difference during running between female runners with current ITBS and controls. Isometric hip abductor strength was also found to be lower in female runners with current ITBS compared to healthy controls<ref name=":2">Foch E, Brindle RA, Pohl MB. Lower extremity kinematics during running and hip abductor strength in iliotibial band syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait & posture. [https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/science/article/pii/S0966636223000334#bib3 2023;101:73–81.]</ref>. | |||

For males, there were associations between ITBS and peak hip adduction angle. There was no difference in peak hip adduction angle during running between male runners with current ITBS and healthy controls<ref name=":2" />. | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

In many instances the subjective assessment will already provide an excellent basis for suspicion of this syndrome. Activities that require repetitive activities involving knee flexion-extension are usually reported, as well as a burning pain at the level of (or just underneath) the lateral femoral epicondyle. The diagnosis in patients with this syndrome is based on different symptoms.<ref name="p6">Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2007; 10:74-76</ref> | |||

The | The main symptom of ITBS is a sharp pain on the outer aspect of the knee, particularly when the heel strikes the floor, that can radiate into the outer thigh or calf.<ref name="John M. Martinez et al.">Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Iliotibial Band Syndrome Differential Diagnoses. 2016.https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/307850 (accessed on 26th of Jul 2018)</ref> The pain tends to be worse when running or coming down stairs. There may be an audible snapping sensation the knee bends due to the band flicks over the bony tubercle. There may also be some swelling on the outer side of the knee. | ||

== | Among the characteristics, we find an exercise-related tenderness over the lateral femoral epicondyle.<ref name="p6" /> The patient may experience, on a regular basis, an acute, burning pain when pressure is applied on the lateral femoral epycondyle with the knee in flexion and in extension.<ref name="p2" /> Signs of inflammation may also be found.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p6" /> There is pain on the lateral aspect of the knee during running, increasing in intensity while running downhill or descending stairs and pain is typically exacerbated when running longer distances.<ref name="p7">Wong M. Pocket Orthopaedics, Evidence-Based survival guide. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2009 .</ref> | ||

The | The first well documented cases of ITBS were performed by Lieutenant Commander James Renne, a medical corps officer who documented on 16 ITBS cases out of 1000 military recruits. The onset occurred most frequently at the lateral knee after 2 miles of running, or hiking over 10 miles. Walking with the knee extended relieved the symptoms. All of the patients had focal tenderness over the lateral femoral epicondyle at 30 of flexion, and 5 patients had an unusual palpation described as “rubbing of a finger over a wet balloon.” <ref name="Roberto Seijas et al.">Seijas R, Sallent R, Galán M, Alvarez-Diaz P, Ares O, Cugat R. Iliotibial Band Syndrome Following Hip Arthroscopy: An unreported complication, Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, 2016; 50(5): 486–491. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.18959.</ref> | ||

The prevalence of ITBS in women is estimated to be between 16% and 50% and for men between 50% and 81%. <ref name="Van Der Worp Maarten et al." /> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

[[Hamstring origin tendinopathy|Biceps femoris tendinopathy]] | |||

Degenerative joint disease | |||

[[Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee|Lateral collateral ligament]] (LCL) injury | |||

[[Meniscal Lesions|Meniscal]] dysfunction or injury | |||

[[Myofascial Pain|Myofascial pain]] | |||

[[Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome|Patellofemoral stress syndrome]] | |||

Popliteal tendinopathy | |||

< | [[Referred Pain|referred pain]] from lumbar spine, stress fractures, and superior tibiofibular joint sprain.<ref name="p8">Khaund R, Flynn SH. Iliotibial band syndrome: a common source of knee pain. American Family Physician. 2005;71(8):1545-1550.</ref> | ||

Knee [[Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow|osteochondritis dissecans]] | |||

[[Overuse Injuries in Sport|Overuse injury]] | |||

Peroneal mononeuropathy | |||

< | [[Trochanteric Bursitis|Trochanteric bursitis]].<ref name="Bischoff Craig et al.">Bischoff C, Prusaczyk WK, Sopchick TL, Pratt NC, Goforth HW. Comparison of phonophoresis and knee immobilization in treating iliotibial band syndrome, Journal of Sports Medicine, Training and Rehabilitation, 1995, 6(1):1-6.https://doi.org/10.1080/15438629509512030</ref> | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

| Line 74: | Line 77: | ||

*[[Noble's test|Noble’s test]] <br> | *[[Noble's test|Noble’s test]] <br> | ||

*[[Ober's Test|Ober’s test]]<br> | *[[Ober's Test|Ober’s test]]<br> | ||

== Outcome Measures == | == Outcome Measures == | ||

*[[Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)|Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)]] | *[[Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)|Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)]] | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Numeric_Pain_Rating_Scale The 11-point numeric pain rating scale from Gunter and Schwellnus] <ref name="Kristoffer Wechström et al."> | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Numeric_Pain_Rating_Scale The 11-point numeric pain rating scale from Gunter and Schwellnus] <ref name="Kristoffer Wechström et al.">Weckström K, Söderström J. Radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy compared with manual therapy in runners with iliotibial band syndrome, Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 2016; 29(1):161-70. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150612. | ||

</ref> | |||

< | |||

[[Image:NRS pain.jpg|center|thumb|418x418px|[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Numeric_Pain_Rating_Scale Figure [2]<nowiki>]</nowiki>]] | |||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

* | *Force of hip abduction: | ||

The force of hip abductors can be decreased. These muscles should thus be tested.<ref name="p6" /> | The force of hip abductors can be decreased. These muscles should thus be tested.<ref name="p6" /> | ||

| Line 94: | Line 92: | ||

*<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Treadmill test: </span> | *<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Treadmill test: </span> | ||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">This test is described in several studies as a valid, effective, and sensitive method of evaluating the effects of treatments for running related pain and is used to measure the amount of pain that subjects experience during normal running. If this includes pain to the lateral side of the knee, the test is considered positive</span><ref name="Kristoffer Wechström et al." /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">.</span> | |||

*<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Noble compression test:</span> | *<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">[[Noble's test|Noble compression test]]:</span> | ||

This test starts in supine posture and a knee flexion of 90 degrees. As the patient extends the knee the assessor applies pressure to the lateral femoral epicondyle. If this induces pain over the lateral femoral epicondyle near 30-40 degrees of flexion, the test is considered positive.<ref name="p2" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> | This test starts in supine posture and a knee flexion of 90 degrees. As the patient extends the knee the assessor applies pressure to the lateral femoral epicondyle. If this induces pain over the lateral femoral epicondyle near 30-40 degrees of flexion, the test is considered positive.<ref name="p2" /> <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">A goniometer is used to ensure the correct angle of the knee joint</span><ref name="Kristoffer Wechström et al." /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">.</span> | ||

*Ober test: | *[[Ober's Test|Ober test]]: | ||

The patient is lying on his side with the injured extremity facing upwards. The knee is flexed at 90 degrees and the hip in abduction and extension, the thigh is maintained in line with the trunk. The patient is invited to adduct the thigh as far as possible. The test is positive if the patient cannot adduct farther than the examination table. A positive Ober test indicates a short / tense ilio-tibial band or tensor fasciae latae, which is frequently related to the friction syndrome.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p0">Gajdosik RL, Sandler MM, Marr HL. Influence of knee positions and gender on the Ober test for length of the iliotibial band | The patient is lying on his side with the injured extremity facing upwards. The knee is flexed at 90 degrees and the hip in abduction and extension, the thigh is maintained in line with the trunk. The patient is invited to adduct the thigh as far as possible. The test is positive if the patient cannot adduct farther than the examination table. A positive Ober test indicates a short / tense ilio-tibial band or tensor fasciae latae, which is frequently related to the friction syndrome.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p0">Gajdosik RL, Sandler MM, Marr HL. Influence of knee positions and gender on the Ober test for length of the iliotibial band. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2003;18(1):77-9</ref> | ||

Both the Noble compression test and the Ober test can be use to examine a patient with a suspicion of Iliotibial friction syndrome. The result will be more obvious when we combine the two into one special test. For this, the position of the Ober test is adopted and compression is applied on the lateral epicondyle during passive knee extension and flexion. Moving the knee can produce more strain on the injured structures and can help to reproduce the symptoms of the patient if the combination does not. Medial patellar glide can also increase the symptoms (by tending the patellar expansion of the iliotibial band) and can reveal the precise localization while lateral glides reduces them. An internal rotation of the tibia when the knee is moved from flexion to extension can also produce the symptoms. A combination of the Nobel and Ober tests with an unloaded knee or in a weight bearing position can also be done the reproduce the symptoms.<ref name="p2" /> | Both the Noble compression test and the Ober test can be use to examine a patient with a suspicion of Iliotibial friction syndrome. The result will be more obvious when we combine the two into one special test. For this, the position of the Ober test is adopted and compression is applied on the lateral epicondyle during passive knee extension and flexion. Moving the knee can produce more strain on the injured structures and can help to reproduce the symptoms of the patient if the combination does not. Medial patellar glide can also increase the symptoms (by tending the patellar expansion of the iliotibial band) and can reveal the precise localization while lateral glides reduces them. An internal rotation of the tibia when the knee is moved from flexion to extension can also produce the symptoms. A combination of the Nobel and Ober tests with an unloaded knee or in a weight bearing position can also be done the reproduce the symptoms.<ref name="p2" /> | ||

== Medical Management == | |||

Treatment of the acute inflammatory response: | |||

== | Activity modification to prevent further aggravation of the patient's symptoms should be the first area to be addressed in treatment. Promoting a period of active rest or substantially decreasing the intensity of the aggravating activities would be a strong starting point. Patients should be advised to participate in other physical activities, such as e.g. swimming, that do not aggravate their symptoms to maintain their conditioning. It is important to work with the patient to find a level of activity that allows them to feel confident in their rehabilitation ability and have a fair understanding of why this reduction in loading is necessary as well as working below their pain threshold <ref name=":0" />. Some authors<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2" /> suggest complete rest from athletic activities for at least 3 weeks; other authors<ref name="p3" /> suggest that it is best to rest a period from 1 week to 2 months, but this rest period depends heavily on each individuals' clinical examination features. | ||

Other modalities that may provide pain relief include ice ([[cryotherapy]]) or heat<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p5">Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D. Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Conditions. 2011;19(12):728-36.</ref>, taping and stretching according to objective findings. | |||

If no improvement of symptoms occurs and inflammation persists, the following other treatment techniques might be considered: | If no improvement of symptoms occurs and inflammation persists, the following other treatment techniques might be considered: | ||

*Ultrasound therapy<ref name="p5" />, providing thermal or non-thermal treatment of the injured tissue at a frequency range of 0.75 to 3 MHz (depending on the depth of the soft tissue to be treated)<ref name="25a">Speed | *Ultrasound therapy<ref name="p5" />, providing thermal or non-thermal treatment of the injured tissue at a frequency range of 0.75 to 3 MHz (depending on the depth of the soft tissue to be treated)<ref name="25a">Speed CA. Therapeutic ultrasound in soft tissue lesions. British Society for Rheumatology, 2001; 40(12): 1331–1336. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/40.12.1331</nowiki></ref> | ||

*Muscle stimulation<ref name="p5" /> | *Muscle stimulation<ref name="p5" /> | ||

*Iontophoresis or phonophoresis<ref name="p5" />, techniques in which medication is administered into the injured tissue through ion distribution driven by an electric field or passed through the skin using ultrasound waves, respectively. | *Iontophoresis or phonophoresis<ref name="p5" />, techniques in which medication is administered into the injured tissue through ion distribution driven by an electric field or passed through the skin using ultrasound waves, respectively. <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Iontophoresis with dexamethasone may be useful as an anti-inflammatory modality. <ref name="Robert L. Baker et al." /> | ||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Phonophoresis has been used in an effort to enhance the absorption of topically applied analgesics and anti- inflammatory agents through the therapeutic application of ultrasound. One study evaluated the efficacy of two ITBS treatments: phonophoresis using ultrasound to transport 10% hydrocortisone into subcutaneous tissues, and knee immobilization; the outcome suggests that receiving phonophoresis is a better treatment than just knee immobilization.<ref name="Gunter P. et al.">Gunter P, Schwellnus MP. Local corticosteroid injection in iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners: A Rrandomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2004; 38(3):269-72; | |||

</ref> </span> | |||

<br> | An alternative treatment strategy is radial shockwave therapy. RSWT is considered safe as it results in minor adverse effects including worsening of symptoms over a short period of time, reversible local swelling, redness and hematoma. RSWT is believed to stimulate healing of soft tissue and to inhibit nociceptors. Thus, it increases the diffusion of cytokines across vessel walls into the painful area and stimulates the tendon healing response. Shockwaves also reduce the non-myelinated sensory nerve fibres and significantly reduce calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), and substance-P release. Finally shockwave treatment may stimulate neo-vascularisation in the tendon-bone and bone junction, thus promoting healing.<br>The shockwave treatment uses energy generated when a projectile in a handpiece is accelerated py pressurized air and hits a 15-mm-diameter metal applicator. The energy is then transmitted from the applicator via ultrasound gel to the skin, where the shockwave disperses radially into the tissue to be treated. <br>Radial shockwave therapy is shown to be really effective as rehabilitation program for runners with iliotibial band syndrome<ref name="Kristoffer Wechström et al." />. '''<u><br>Physical Therapy Management</u>''' | ||

A systematic review suggested that during follow up at 6 months, conservative treatment was effective at pain-reduction for ITBS<ref name=":1" />. The treatment of ITBS is usually non-operative, and physiotherapy should be considered the first and best line of treatment. | |||

< | *Exercises to stretch the iliotibial band are no longer considered as a strong evidence-based treatment approach. The best exercises to start will depend on the causative factors obtained from the subjective and objective assessment. If the lateral gluteal muscles are found to be weak or functioning improperly, this will result in compensatory muscle adaptation which can lead to excessive contraction of the iliotibial band.<ref name="p7" /> If the gluteal groups are too short, external rotation of the leg can occur and create abnormal stress on the iliotibial band.<ref name="21a">Krista Simon; Iliotibial Band Syndrome; Nysportsmed, 2015. </ref><ref name="Van Der Worp Maarten et al.">van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 2012;42(11):969-92. | ||

</ref> | |||

*<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Myofascial treatment can be effective in reducing the pain experience in acute phase, when pain and inflammation in the insertion is felt. The trigger points in Biceps femoris, vastus lateralis, gluteus maximus, and tensor fascia latae muscles will be addressed by a myofascial treatment.<ref name="Robert L. Baker et al.">Baker RL, Fredericson M. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners : Biomechanical Implications and Exercise Interventions. Physical médicine and réhabilitation clinics of North America, 2016; 27(1):53-77 | |||

</ref> | |||

*<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">The use of a foam roller on the tight muscles could also be beneficial.</span><ref name="p7" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> </span>The patient can also perform exercises using a foam roller at home to create deep transversal friction, self myofascial release (massage) and stretching of the muscles. A possible exercise is to lie on the side with the foam roller positioned perpendicular to the bottom leg, just below the hipbone. The upper leg should be positioned in front for balance. Using the hands for support, roll from the top of the outer thigh down to just above the knee, straightening the front leg during the movement. <ref name="Jerold M. Stirling et al.">Jerold M. Stirling et al., Iliotibial Band Syndrome Treatment & Management. Sports Medicine, 2015.https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/91129 Accessed on 30 Jul 2018</ref> | |||

*Exercises to strengthen the abductor muscles and stabilise the hip can be helpful if clinically indicated. Here some some rehabilitative strengthening exercises: | |||

1-Hip Bridge with Resistance Band: An effective yet simple exercise to begin with is the hip bridge utilizing a resistance band. Researchers Choi and colleagues found that gluteus maximus EMG activity was significantly greater while anterior pelvic tilt angle was significantly lower in the glute bridge with isometric hip abduction compared to the glute bridge without the band. Therefore, they concluded that performing glute bridges with isometric hip abduction against isometric elastic resistance can be used to increase gluteus maximus EMG activity and reduce anterior pelvic tilt during the exercise. | |||

2-Side Lying Hip Abduction: The Side Lying Hip Abduction is a great way to isolate the glute medius. Distefano and colleagues looked at gluteal activation among common exercises and identified this as one of the top exercises. | |||

3- Lateral Band Walk: Once you have isolated the gluteus medius you can now integrate a more functional exercise with the lateral band walk. Increased hip abduction strength has been shown to improve the ability of female athletes to control lower extremity alignment. When performing this exercise, the stepping motion should be performed in a semi-squat position with the knees bent rather than an upright straight leg position in order to generate greater gluteus maximus and medius muscle activity<ref>Berry et al. 2015. Resisted side-stepping: the effect of posture on hip abductor muscle activation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy" /></ref>. | |||

4-Side [[Plank exercise|Plank]]: start by performing 3-5 repetitions for 10 seconds each, gradually adding more repetitions. | |||

Since ITBS can often be associated with hip abductor weakness, strengthening and stabilising of the hip will be beneficial in the treatment of ITBS.<ref name="p3" /> Some examples of useful exercises: Hip hikes to strengthen the gluteus medius help stabilize the hip. Stand on the edge of a step with the majority of the body weight on the unaffected side. Lower the hip of the involved hip and bring it back to neutral.<ref name="p6" /> Another example is the side-lying hip abduction (Figure [3])exercise with the back against a wall and the leg held at approximately 30° of hip abduction with slight hip external rotation and neutral hip extension. This exercise can be made more strenuous by placing a 1-metre-long band between the ankles.<ref name="p3" /> | |||

[[Image:Hips1.jpg|frame|center|[http://www.ultimatebodypress.com/hip-abduction.html Figure [3]<nowiki>]</nowiki>]] | |||

| | |||

Other exercises that are recommended, given the relationship of lowering body weight on one leg and neuromuscular control, are the ‘single-leg step down’ (Figure [4]), the ‘single-leg wall squat’ (Figure [5]) and the ‘single-leg dead lift’ (Figure [6]). <ref name="p0" /> | |||

[[Image:Slsd.jpg|frame|left|[https://www.researchgate.net/figure/286901115_fig11_Fig-11-Single-leg-step-down-test-and-exercise-If-tolerated-several-repetitions-can-be Figure [4]<nowiki>]</nowiki>]][[Image:Single-Leg-Wall-Squat.png|frame|center| [http://twicethespeed.com/blog/home Figure [5]<nowiki>]</nowiki>]] | |||

< | [[Image:Sldl.gif|frame|center|[http://www.menshealth.com/fitness/ultimate-body-weight-workout Figure [6]<nowiki>]</nowiki>]] | ||

*<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Hip/knee coordination and running/cycling style modification through the increase of neuromuscular control of gait.</span><ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /> | |||

*Cyclist are also at risk for ITBS if they tend to pedal with their toes turned in, so implementing the optimal pedalling technique may minimise the risk of developing symptoms.<ref name="p7" /> | |||

== Surgical Management == | |||

Open and arthroscopic surgery were shown as effective for returning athletes to sport, at a percentage between 81 and 100<ref name=":1" />. During surgery, a small piece of the posterior part of the iliotibial band that covers the lateral femoral epicondyle will be resected.<ref name="p5" />There is also some low level evidence to <ref name="p1" /> support resolution of ITBS from the surgical excision of a bursa, cyst, or portion of a lateral synovial recess. | |||

Surgical intervention for ITBS is often thought of as a 2nd-line treatment in which prolonged conservative treatment has failed to either alleviate the patient's symptoms or resolve ITBS. However, there is a dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of conservative therapy, so patients with ITBS could possibly miss less time from sport participation if surgery was initially performed without trialing conservative treatment first<ref name=":1" />. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

< | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Injuries]] | |||

Revision as of 18:55, 10 April 2024

Original Editors - Yves Demol, Aurelie Ackerman

Top Contributors - Sue Safadi, Aurélie Ackerman, Houpe Maureen, Johnathan Fahrner, Demol Yves, Elvira Muhic, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Claire Knott, Kenneth de Becker, 127.0.0.1, Daphne Jackson, Jonathan Wong, Mohit Chand, WikiSysop, Joao Costa, Jennifer Uytterhaegen, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly, Lucinda hampton, Chloe Wilson, George Prudden, Kai A. Sigel, Adam Vallely Farrell, Wout Fransen and Thomas De Pauw

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

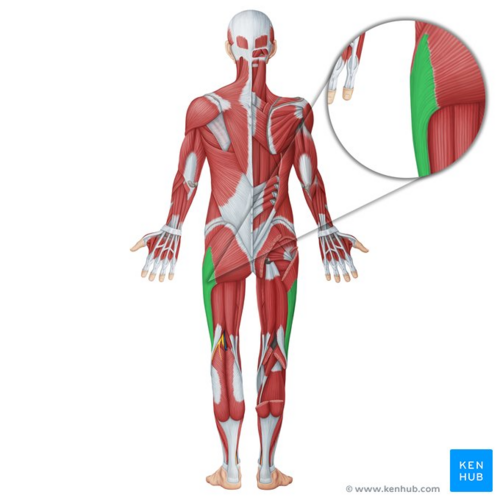

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common knee condition that usually presents with pain and/or tenderness on palpation of the lateral aspect of the knee, superior to the joint line and inferior to the lateral femoral epicondyle.[1]. It is considered a non-traumatic overuse injury, often seen in runners, and is often concomitant with underlying weakness of hip abductor muscles.[2] [3]. The current theory is that this condition is likely to be caused by compression of the innervated local adipose tissue[4].Studies have described an ‘impingement zone’ occurring at, or slightly below, 30° of knee flexion during foot strike and the early stance phase of running. During this impingement period in the running cycle, eccentric contraction of the tensor fascia latae muscle and of the gluteus maximus causes the leg to decelerate, generating tension (compression) in the iliotibial band.[5]

Image: Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view[6]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

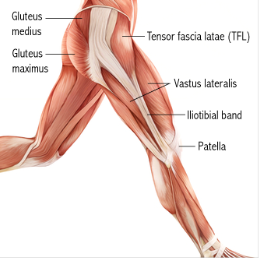

The iliotibial tract is a thick band of fascia that runs on the lateral side of the thigh from the iliac crest and inserts at the knee.[7] It is composed of dense fibrous connective tissue that appears from the m. tensor fasciae latae and m. gluteus maximus. It descends along the lateral aspect of the thigh, between the layers of the superficial fascia, and inserts onto the lateral tibial plateau at a projection known as Gerdy’s tubercle[2]. In its distal portion the iliotibial tract covers the lateral femoral epicondyle and gives an expansion to the lateral border of the patella. While the iliotibial band does not have any boney attachments as it courses between the Gerdy tubercle and the lateral femoral epicondyle, this absence of attachment allows it to move anteriorly and posteriorly with knee flexion and extension.

Histologic and dissection study of the iliotibial band at the lateral femoral epicondyle and gluteus maximus and fascia latae suggest a mechanosensory role acting proximally on the anterolateral knee. Figure [1] This mechanosensory role may affect the interpretation of the ligament versus tendon function of the ITB from hip to lateral femoral epicondyle.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

ITBS is one of the most common injuries in runners presenting with lateral knee pain, with an incidence estimated to between 5% and 14%. [8] Further studies indicate ITBS is responsible for approximately 22% of all lower extremity injuries.[1]

ITBS is a common cause of knee pain laterally, especially in athletes for sports involving repeated knee flexion and extension, such as cyclists and runners[9]. Recent evidence suggests ITB contributes to rotational knee stability as well, and therefore, pivoting sports might increase the risk for ITBS[10].

The ITBS disease process is multifactorial, and various mechanisms have been suggested for it: repeated rubbing of the iliotibial band on the lateral femoral epicondyle during knee flexion and extension; iliotibial band impingement at 30° knee flexion; weakness of hip abductors resulting in iliotibial band overtightening during knee flexion–extension; lateral synovial recess or sub-iliotibial band bursa of the lateral knee inflammation; lateral epicondyle periosteal inflammation; and others[11].

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Due to the difference in male and female anatomy, risk factors have been considered separately for each group.

A systematic review suggests associations between ITBS and peak hip adduction angle, peak hip internal rotation angle, peak knee internal rotation angle, and isometric hip abductor strength in female runners. Female runners with current ITBS have less hip internal rotation during stance phase of running compared to healthy controls. However, peak hip adduction angle had no difference during running between female runners with current ITBS and controls. Isometric hip abductor strength was also found to be lower in female runners with current ITBS compared to healthy controls[12].

For males, there were associations between ITBS and peak hip adduction angle. There was no difference in peak hip adduction angle during running between male runners with current ITBS and healthy controls[12].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

In many instances the subjective assessment will already provide an excellent basis for suspicion of this syndrome. Activities that require repetitive activities involving knee flexion-extension are usually reported, as well as a burning pain at the level of (or just underneath) the lateral femoral epicondyle. The diagnosis in patients with this syndrome is based on different symptoms.[13]

The main symptom of ITBS is a sharp pain on the outer aspect of the knee, particularly when the heel strikes the floor, that can radiate into the outer thigh or calf.[14] The pain tends to be worse when running or coming down stairs. There may be an audible snapping sensation the knee bends due to the band flicks over the bony tubercle. There may also be some swelling on the outer side of the knee.

Among the characteristics, we find an exercise-related tenderness over the lateral femoral epicondyle.[13] The patient may experience, on a regular basis, an acute, burning pain when pressure is applied on the lateral femoral epycondyle with the knee in flexion and in extension.[3] Signs of inflammation may also be found.[1][13] There is pain on the lateral aspect of the knee during running, increasing in intensity while running downhill or descending stairs and pain is typically exacerbated when running longer distances.[15]

The first well documented cases of ITBS were performed by Lieutenant Commander James Renne, a medical corps officer who documented on 16 ITBS cases out of 1000 military recruits. The onset occurred most frequently at the lateral knee after 2 miles of running, or hiking over 10 miles. Walking with the knee extended relieved the symptoms. All of the patients had focal tenderness over the lateral femoral epicondyle at 30 of flexion, and 5 patients had an unusual palpation described as “rubbing of a finger over a wet balloon.” [16]

The prevalence of ITBS in women is estimated to be between 16% and 50% and for men between 50% and 81%. [8]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Degenerative joint disease

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury

Meniscal dysfunction or injury

Patellofemoral stress syndrome

Popliteal tendinopathy

referred pain from lumbar spine, stress fractures, and superior tibiofibular joint sprain.[17]

Knee osteochondritis dissecans

Peroneal mononeuropathy

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There are different provocative tests:

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)

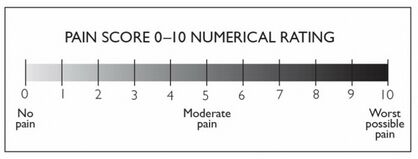

- The 11-point numeric pain rating scale from Gunter and Schwellnus [19]

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Force of hip abduction:

The force of hip abductors can be decreased. These muscles should thus be tested.[13]

- Treadmill test:

This test is described in several studies as a valid, effective, and sensitive method of evaluating the effects of treatments for running related pain and is used to measure the amount of pain that subjects experience during normal running. If this includes pain to the lateral side of the knee, the test is considered positive[19].

This test starts in supine posture and a knee flexion of 90 degrees. As the patient extends the knee the assessor applies pressure to the lateral femoral epicondyle. If this induces pain over the lateral femoral epicondyle near 30-40 degrees of flexion, the test is considered positive.[3] A goniometer is used to ensure the correct angle of the knee joint[19].

The patient is lying on his side with the injured extremity facing upwards. The knee is flexed at 90 degrees and the hip in abduction and extension, the thigh is maintained in line with the trunk. The patient is invited to adduct the thigh as far as possible. The test is positive if the patient cannot adduct farther than the examination table. A positive Ober test indicates a short / tense ilio-tibial band or tensor fasciae latae, which is frequently related to the friction syndrome.[1][20]

Both the Noble compression test and the Ober test can be use to examine a patient with a suspicion of Iliotibial friction syndrome. The result will be more obvious when we combine the two into one special test. For this, the position of the Ober test is adopted and compression is applied on the lateral epicondyle during passive knee extension and flexion. Moving the knee can produce more strain on the injured structures and can help to reproduce the symptoms of the patient if the combination does not. Medial patellar glide can also increase the symptoms (by tending the patellar expansion of the iliotibial band) and can reveal the precise localization while lateral glides reduces them. An internal rotation of the tibia when the knee is moved from flexion to extension can also produce the symptoms. A combination of the Nobel and Ober tests with an unloaded knee or in a weight bearing position can also be done the reproduce the symptoms.[3]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment of the acute inflammatory response:

Activity modification to prevent further aggravation of the patient's symptoms should be the first area to be addressed in treatment. Promoting a period of active rest or substantially decreasing the intensity of the aggravating activities would be a strong starting point. Patients should be advised to participate in other physical activities, such as e.g. swimming, that do not aggravate their symptoms to maintain their conditioning. It is important to work with the patient to find a level of activity that allows them to feel confident in their rehabilitation ability and have a fair understanding of why this reduction in loading is necessary as well as working below their pain threshold [4]. Some authors[1][3] suggest complete rest from athletic activities for at least 3 weeks; other authors[2] suggest that it is best to rest a period from 1 week to 2 months, but this rest period depends heavily on each individuals' clinical examination features.

Other modalities that may provide pain relief include ice (cryotherapy) or heat[1][21], taping and stretching according to objective findings.

If no improvement of symptoms occurs and inflammation persists, the following other treatment techniques might be considered:

- Ultrasound therapy[21], providing thermal or non-thermal treatment of the injured tissue at a frequency range of 0.75 to 3 MHz (depending on the depth of the soft tissue to be treated)[22]

- Muscle stimulation[21]

- Iontophoresis or phonophoresis[21], techniques in which medication is administered into the injured tissue through ion distribution driven by an electric field or passed through the skin using ultrasound waves, respectively. Iontophoresis with dexamethasone may be useful as an anti-inflammatory modality. [7]

Phonophoresis has been used in an effort to enhance the absorption of topically applied analgesics and anti- inflammatory agents through the therapeutic application of ultrasound. One study evaluated the efficacy of two ITBS treatments: phonophoresis using ultrasound to transport 10% hydrocortisone into subcutaneous tissues, and knee immobilization; the outcome suggests that receiving phonophoresis is a better treatment than just knee immobilization.[23]

An alternative treatment strategy is radial shockwave therapy. RSWT is considered safe as it results in minor adverse effects including worsening of symptoms over a short period of time, reversible local swelling, redness and hematoma. RSWT is believed to stimulate healing of soft tissue and to inhibit nociceptors. Thus, it increases the diffusion of cytokines across vessel walls into the painful area and stimulates the tendon healing response. Shockwaves also reduce the non-myelinated sensory nerve fibres and significantly reduce calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), and substance-P release. Finally shockwave treatment may stimulate neo-vascularisation in the tendon-bone and bone junction, thus promoting healing.

The shockwave treatment uses energy generated when a projectile in a handpiece is accelerated py pressurized air and hits a 15-mm-diameter metal applicator. The energy is then transmitted from the applicator via ultrasound gel to the skin, where the shockwave disperses radially into the tissue to be treated.

Radial shockwave therapy is shown to be really effective as rehabilitation program for runners with iliotibial band syndrome[19].

Physical Therapy Management

A systematic review suggested that during follow up at 6 months, conservative treatment was effective at pain-reduction for ITBS[11]. The treatment of ITBS is usually non-operative, and physiotherapy should be considered the first and best line of treatment.

- Exercises to stretch the iliotibial band are no longer considered as a strong evidence-based treatment approach. The best exercises to start will depend on the causative factors obtained from the subjective and objective assessment. If the lateral gluteal muscles are found to be weak or functioning improperly, this will result in compensatory muscle adaptation which can lead to excessive contraction of the iliotibial band.[15] If the gluteal groups are too short, external rotation of the leg can occur and create abnormal stress on the iliotibial band.[24][8]

- Myofascial treatment can be effective in reducing the pain experience in acute phase, when pain and inflammation in the insertion is felt. The trigger points in Biceps femoris, vastus lateralis, gluteus maximus, and tensor fascia latae muscles will be addressed by a myofascial treatment.[7]

- The use of a foam roller on the tight muscles could also be beneficial.[15] The patient can also perform exercises using a foam roller at home to create deep transversal friction, self myofascial release (massage) and stretching of the muscles. A possible exercise is to lie on the side with the foam roller positioned perpendicular to the bottom leg, just below the hipbone. The upper leg should be positioned in front for balance. Using the hands for support, roll from the top of the outer thigh down to just above the knee, straightening the front leg during the movement. [25]

- Exercises to strengthen the abductor muscles and stabilise the hip can be helpful if clinically indicated. Here some some rehabilitative strengthening exercises:

1-Hip Bridge with Resistance Band: An effective yet simple exercise to begin with is the hip bridge utilizing a resistance band. Researchers Choi and colleagues found that gluteus maximus EMG activity was significantly greater while anterior pelvic tilt angle was significantly lower in the glute bridge with isometric hip abduction compared to the glute bridge without the band. Therefore, they concluded that performing glute bridges with isometric hip abduction against isometric elastic resistance can be used to increase gluteus maximus EMG activity and reduce anterior pelvic tilt during the exercise.

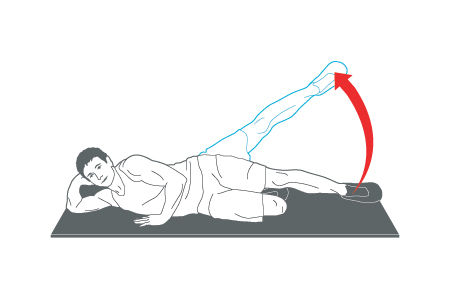

2-Side Lying Hip Abduction: The Side Lying Hip Abduction is a great way to isolate the glute medius. Distefano and colleagues looked at gluteal activation among common exercises and identified this as one of the top exercises.

3- Lateral Band Walk: Once you have isolated the gluteus medius you can now integrate a more functional exercise with the lateral band walk. Increased hip abduction strength has been shown to improve the ability of female athletes to control lower extremity alignment. When performing this exercise, the stepping motion should be performed in a semi-squat position with the knees bent rather than an upright straight leg position in order to generate greater gluteus maximus and medius muscle activity[26].

4-Side Plank: start by performing 3-5 repetitions for 10 seconds each, gradually adding more repetitions.

Since ITBS can often be associated with hip abductor weakness, strengthening and stabilising of the hip will be beneficial in the treatment of ITBS.[2] Some examples of useful exercises: Hip hikes to strengthen the gluteus medius help stabilize the hip. Stand on the edge of a step with the majority of the body weight on the unaffected side. Lower the hip of the involved hip and bring it back to neutral.[13] Another example is the side-lying hip abduction (Figure [3])exercise with the back against a wall and the leg held at approximately 30° of hip abduction with slight hip external rotation and neutral hip extension. This exercise can be made more strenuous by placing a 1-metre-long band between the ankles.[2]

Other exercises that are recommended, given the relationship of lowering body weight on one leg and neuromuscular control, are the ‘single-leg step down’ (Figure [4]), the ‘single-leg wall squat’ (Figure [5]) and the ‘single-leg dead lift’ (Figure [6]). [20]

- Hip/knee coordination and running/cycling style modification through the increase of neuromuscular control of gait.[1][15]

- Cyclist are also at risk for ITBS if they tend to pedal with their toes turned in, so implementing the optimal pedalling technique may minimise the risk of developing symptoms.[15]

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Open and arthroscopic surgery were shown as effective for returning athletes to sport, at a percentage between 81 and 100[11]. During surgery, a small piece of the posterior part of the iliotibial band that covers the lateral femoral epicondyle will be resected.[21]There is also some low level evidence to [1] support resolution of ITBS from the surgical excision of a bursa, cyst, or portion of a lateral synovial recess.

Surgical intervention for ITBS is often thought of as a 2nd-line treatment in which prolonged conservative treatment has failed to either alleviate the patient's symptoms or resolve ITBS. However, there is a dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of conservative therapy, so patients with ITBS could possibly miss less time from sport participation if surgery was initially performed without trialing conservative treatment first[11].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Lavine R. Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2010; 3(1-4) :18–22

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal of Anatomy, 2006; 208(3): 309-316

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Michael D. Clinical Testing for Extra-Articular Lateral Knee Pain: A Modification and Combination of Traditional Tests. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 2008; 3: 107–109.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lazenby, T & Geisler, P (2017). Iliotibial Band Impingement Syndrome: An Updated Evidence-Informed Clinical Paradigm. Published 2017/03/06 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22882.53448

- ↑ van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 2012; 42(11):969-92

- ↑ Iliotibial tract (highlighted in green) - posterior view image - © Kenhub https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/iliotibial-band

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Baker RL, Fredericson M. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners : Biomechanical Implications and Exercise Interventions. Physical médicine and réhabilitation clinics of North America, 2016; 27(1):53-77

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Sport Medicine, 2012;42(11):969-92.

- ↑ Aderem, J., 2015. The biomechanical risk factors associated with preventing and managing iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review.

- ↑ Godin JA, Chahla J, Moatshe G, Kruckeberg BM, Muckenhirn KJ, Vap AR, Geeslin AG, LaPrade RF. A comprehensive reanalysis of the distal iliotibial band: quantitative anatomy, radiographic markers, and biomechanical properties. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017 Sep;45(11):2595-603.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Bolia IK, Gammons P, Scholten DJ, Weber AE, Waterman BR. Operative Versus Nonoperative Management of Distal Iliotibial Band Syndrome—Where Do We Stand? A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation. 2020;2(4):e399–e415.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Foch E, Brindle RA, Pohl MB. Lower extremity kinematics during running and hip abductor strength in iliotibial band syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait & posture. 2023;101:73–81.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, Best TM, Benjamin M. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2007; 10:74-76

- ↑ Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Iliotibial Band Syndrome Differential Diagnoses. 2016.https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/307850 (accessed on 26th of Jul 2018)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Wong M. Pocket Orthopaedics, Evidence-Based survival guide. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2009 .

- ↑ Seijas R, Sallent R, Galán M, Alvarez-Diaz P, Ares O, Cugat R. Iliotibial Band Syndrome Following Hip Arthroscopy: An unreported complication, Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, 2016; 50(5): 486–491. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.18959.

- ↑ Khaund R, Flynn SH. Iliotibial band syndrome: a common source of knee pain. American Family Physician. 2005;71(8):1545-1550.

- ↑ Bischoff C, Prusaczyk WK, Sopchick TL, Pratt NC, Goforth HW. Comparison of phonophoresis and knee immobilization in treating iliotibial band syndrome, Journal of Sports Medicine, Training and Rehabilitation, 1995, 6(1):1-6.https://doi.org/10.1080/15438629509512030

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Weckström K, Söderström J. Radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy compared with manual therapy in runners with iliotibial band syndrome, Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 2016; 29(1):161-70. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150612.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gajdosik RL, Sandler MM, Marr HL. Influence of knee positions and gender on the Ober test for length of the iliotibial band. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2003;18(1):77-9

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calcei JG, Park D. Iliotibial band syndrome: evaluation and management. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Conditions. 2011;19(12):728-36.

- ↑ Speed CA. Therapeutic ultrasound in soft tissue lesions. British Society for Rheumatology, 2001; 40(12): 1331–1336. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/40.12.1331

- ↑ Gunter P, Schwellnus MP. Local corticosteroid injection in iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners: A Rrandomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2004; 38(3):269-72;

- ↑ Krista Simon; Iliotibial Band Syndrome; Nysportsmed, 2015.

- ↑ Jerold M. Stirling et al., Iliotibial Band Syndrome Treatment & Management. Sports Medicine, 2015.https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/91129 Accessed on 30 Jul 2018

- ↑ Berry et al. 2015. Resisted side-stepping: the effect of posture on hip abductor muscle activation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy" />