Labral Tear

Original Editors - Bilitis Crokaert

Top Contributors - Bilitis Crokaert, Admin, Kim Jackson, Daphne Jackson, Evan Thomas, Anas Mohamed, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Vidya Acharya, Wanda van Niekerk, Shreya Pavaskar, Ahmed M Diab and Trista Chan

Definition/Description

[edit | edit source]

An acetabular labral tear can cause pain if the labrum is torn, frayed, or damaged. Labral tears cause groin pain or pain in the anterior side of the hip, and less commonly buttock pain[1]. This mechanically induced pathology is thought to result from excessive forces at the hip joint for example: A tear could decrease the acetabular contact area and increase stress, which would result in articular damage, and destabilize the hip joint[2].

Anterior labral tears: the pain is more consistent and is situated on the anterior hip (anterosuperior quadrant) or at the groin. [3][4][5][6][7][8] They frequently occur in European countries and the United States.

Posterior labral tears: are situated in the lateral region or deep in the posterior buttocks. They are less frequently in European Countries and United states but are frequent in Japan [3][5][7].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

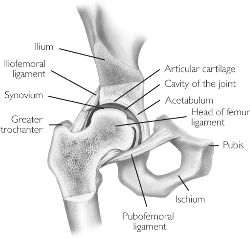

The acetabular labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim, which encompasses the circumference of the acetabulum. It helps to keep the head of the femur inside the acetabulum, and varies greatly in form and thickness.

The labrum has 3 surfaces: internal articular surface next to the joint (avascular), external articular surface(vascular) contacting the joint capsule, and a basal surface that is attached to the acetabular bone and ligaments. The transverse ligaments surround the hip and help hold it in place while moving.

On the anterior side the labrum is triangular in the radial section and posterior side it is dimensionally square but with a rounded distal surface[9][10].

The functions of the acetabular labrum are: joint stability, sensitive shock absorber, joint lubricator, and pressure distributor; decreasing contact stress between the acetabular and the femoral cartilage[5]Byrd JW, Jones KS. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2000;16:578-87.</ref>[11][1]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

In studies of patients with a labral tear, researchers have attributed the injury to a variety of causes.

- Direct trauma: motor accidents, falling with or without a hip dislocation, slipping.

- Sporting activities that require frequent external rotations or hyperextension: ballet, soccer, and hockey, running and sprinting.

- Specific movements incl. torsional or twisting movements :hyper abduction, hyperextension and hyperextension with lateral rotation.

- It is not age related: the reported age of people with hip pain and a labral tear goes from 8 to 75 years old.

- Structural risk factors: acetabular dysplasia, degeneration, capsular laxity/ hip hypermobility and femeroacetabular impingement (FAI) (Byrd and Jones 2003, Wenger et al. 2004). [2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Sex: The both sexes have the same frequency[12][8][13][14]

- Symptoms: A constant dull pain with periods of sharp pain that worsens during activity. Walking, pivoting, prolonged sitting and impact activities aggravate symptoms. Some of the patients describe night-pain[1]. The symptoms can have a long duration, with an average greater than 2 years[15]

- Mechanical Symptoms: variety of mechanical symptoms, including clicking (most frequently),locking or catching, or giving away. The significance of these signs are questionable[16]

- Range of motion:

These specific manoeuvres may cause pain in the groin: [9]

- flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the hip joint = anterior superior tear

- passive hyperextension, abduction, and external rotation = posterior tears

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The differential diagnosis of labral tears should include following diagnoses: athletic pubalgia, Snapping_Hip, Septic Arthritis, piriformis syndrome, contusion, strain, osteitis pubis, Trochanteric Bursitis, femoral head avascular necrosis, fracture, dislocation, inguinal or femoral hernia, Legg-Calve Perthes disease, Slipped_Capital_Femoral_Epiphysis, referred pain from the lumbosacral and sacroiliac areas or a tumor.[17]

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

Includes relative rest, anti-inflammatory medications, and pain medications if necessary. Combined with a 10-12 week intensive physiotherapy. The pain of the patient can reduce during that period but it is possible that the pain returns back to once the patient starts his normal activities. When the conservative measures do not control the patient’s symptoms surgery is possible. [18]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical examination:[19][20]

these tests are considered positive if the patient had one or more symptoms during the tests: click, clunk, pain in the groin region.

- The most consistent test is the impingement test: hip joint was passively flexed to 90°, internally rotated, and adduced.

- FABER test: the lower extremity was passively place in a figure- of – four position, and slight pressure was applied to the medial side of the knee. (Positive in 7 of 18 cases)

- Resisted straight leg raise test, the patient flex the hip joint (30°) with knee-extension + downward pressure.(Positive in 1 of 18 cases)

- McCarthy sign / Thomas hip flexion-to extension manoeuvre: in supine, the subject folly flexed both hips, than the examiner slowly/passively extended the subject’s lower extremities with hips going into external rotation. Repeating the test, but at this time with the hip in internal rotation.

- Internal rotation load/ grind test: in supine, the examiner flexed the subject’s hip passively to 100° and then rotated the subject’s hip from internal rotation to external rotation while pushing along the axis of the femur trough the knee to cause ‘grind’.

- Fitzgerald Test: to test to anterior labarum. Acute flexion of the hip with external rotation and full abduction, followed by extension, abduction, and internal rotation

- Patrick test: to test posterior labrum: extension, abduction, and external rotation brought to a flexed, adducted, and internally rotated position

Diagnostic tests:[21]

- MRA (magnetic resonance arthography) produces the best result, as the intra-articular or systemic infusion of gadolinium is required to obtain the detail necessary to study the labrum. The principle of the procedure relies upon capsular distension. The outline the labrum with contrast and filling any tears that may be present. MRA has limitations regarding the sensivity for diagnose acetabular labral and articular cartilage abnormalities, it has also been proven that MRA may be less effective in identifying posterior and lateral tears.

- Diagnostic-image-guided intra-articular hip injections can also be helpful in the diagnosis of labral tears.

-Hip arthroscopy is used as a diagnostic gold standard for ALT and is used as therapeutic medium.

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

[22]-Arthroscopy

Repair of the acetabular labral lesion can be preformed in either the supine or lateral position. In the supine position, a stand fracture table is used with an oversized perinal post to apply traction. The affected hip is placed into slight extension/adduction to allow approach to the joint. During traction it is important that there is a minimized pressure in the perineal area to avoid neurologic complications. The procedure is under the guidance of fluoroscopy. If the distraction is obtain a 14 or a 16 gauge spinal needle is inserted into the joint to break the vacuum seal and allow further distraction. Three portals are used (the anterolateral, anterior and the distal lateral accessory).

For repair of a detached labrum, the edges of the tear are delineated and suture anchors are placed on top of the acetabular rim in the area of detachment. If the tear in the labrum has a secure outer rim and is still attached to the acetabulum, a suture in the mid substance of the tear can be used to secure.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MJc7JHjfz1Q

Physical Therapy Management [23]

[edit | edit source]

It is important that the physiotherapist stays up the date with the most current techniques and that there is a good communication between the PT and the orthopaedic surgeon; this is because the size and the exact location of the labral tear need to be known.

Movements that cause stress in the area need to be avoided. The rehabilitation protocol following acetabular labral debridement or repair are divided in four phases.

Phase 1. Initial exercise (week 1-4)

The primary goals following a acetabularlabral debridement or repair is to the minimize the pain and the inflammation, and initiate early motion exercises. This phase initially consists of isometrics contraction for the hip adductors, abductors, transverse abdominals and extensor. For a labral debridement closed-chain activities of low-level leg press or shuttle can begin with a limited resistance.

Weight bearing for a debridement is 50% during 7 to 10 days and non-weight bearing of toe-touch weight bearing for 3 to 6 weeks in case of a labral repair. Unnecessary hypomobility will limit the progress in future phases, so please pay attention on it.

Treatment modalities:

- Aquatic therapy is an excellent resource, the ambulation in the water allows for improvement in the gait by allowing appropriate loads to the joint without causing unnecessary stress to the healing tissue for example: Light jogging in the water using a flotation device. It is import to know that the range of motion precautions may vary in debridement or repair.

- Manual therapy for pain reduction and improvement in joint mobility and proprioception. Considerations include gentle hip joint mobilizations contract-relax stretching for internal and external rotation, long axis distraction, and assessment of lumbo-sacral mobility,

- Cryotherapy

- Appropriate pain management through medication.

- Gentle stretching of hip muscle groups incl. piriformis, psoas, quadriceps, hamstring muscles with passive range of motion.

- Stationary bike without resistance, with seat height that limits the hip to less than 90°

- exercises such as; water walking, piriformis stretch, ankle pumps

To go the phase 2 the ROM has to be greater or equal to 75%.

Phase 2. Intermediate exercise (week 5-7)

On this phase we will try to continue the ROM and soft tissue flexibility . Manual therapy should continue with mobilization that is more aggressieve the passive ROM exercises should become more aggressive as needed, for external- and internal rotation.

- Flexibility exercises involving the piriformis, adductor group, psoas/rectus femoris should continue.

- Stationary bike with resistance.

- Sidestepping with an abductor band dor resistance

- core strengthening such as bridging on to legs.

- Non-competitive swimming

- exercises such as; wall sits with abductor band, two leg bridging

To go the third phase it is important that the patient has a normal gait pattern with no Trendelenburg sign. The patient should have symmetrical and passive ROM measurement with minimal complaints of pain.

Phase 3. Advanced Exercise (week 8-12)

- Manual therapy should be performed as needed

- Flexibility and passive ROM interventions should become slightly more aggressive if the limitations consist. ( if the patient has reached his full ROM or flexibility , terminal stretches should be initiated)

- Strengthening exercises ; walking lunges, lunges with trunk rotations, resistend sportcord walking forward/backwards/;;, plyometric bounding in the water, ..

- Exercises such as; core ball stabilization, golf progression, lunges

To go to the forth phases it is important that there are symmetrical ROM and flexibility of the psoas and piriformis.

Phase 4. Sport specific training (12-*)

On this phase it is important to return safely and effectively back to competition or previous activity level. Manual therapy, flexibility, and ROM exercises can to continued.

It is important the the patient had a good muscular endurance, good eccentric control, and the ability to generate power.

The patient can be given sportspecific exercises and has to have the ability to demonstrate a good neuromuscular control of the lower extremity during the activities.

exercises such as; sport specific drills, functional testing

Key Research[edit | edit source]

http://www.jbiomech.com/article/S0021-9290(09)00652-6/abstract

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2953315/pdf/najspt-04-038.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8738000

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20511439

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20015494

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2953303/?tool=pubmed

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15116646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8738000

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21509119

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Groh MM, Herrera J. A comprehensive review of labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2009 Jun;2(2):105-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lewis CL, Sahrmann SA. Acetabular Labral Tears. Phys Ther 2006;86:110-121.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR, et al. The Otto E. Aufranc Award: the role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop 2001;393:25–37.

- ↑ O’Leary JA, Berend K, Vail TP. The relationship between diagnosis and outcome in arthroscopy of the hip. Arthroscopy 2001;17:181–188.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Byrd JW. Labral lesions: an elusive source of hip pain case reports and literature review. Arthroscopy 1996;12:603–612.

- ↑ Binningsley D. Tear of the acetabular labrum in an elite athlete. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:84–88.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hase T, Ueo T. Acetabularlabral tear: arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy 1999;15:138 –141.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome: a clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:423– 429.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Narvani AA, Tsiridis E, Tai CC, Thomas P. Acetabular labrum and its tears. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:207-211.

- ↑ Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes; a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport 1995;27:76-9

- ↑ Martin RL, Enseki KR, Draovitch P, et al. Acetabular labral tears of the hip: examination and diagnostic challanges. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:503-15.

- ↑ Dorrell JH, Catterall A. A torn acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg 1986;68:400-3.

- ↑ Fitzgerald RH. Acetabular labrum tears. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995 Feb;(311):60-8.

- ↑ Leunig M, Werlen S, Ungersbock A, et al. Evaluation of the acetabulum labrum by MR arthrograpy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997;79:230-4

- ↑ Farjo LA, Glick JM, Sampson TG. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy 1999;15:132–137.

- ↑ Leibold M, Huijbregts P, Jensen R. Concurrent criterion-related validity of physical examination tests for hip labral lesions: a systematic review. J Manual Manip Ther 2008;16:24-41

- ↑ Schmerl M, Pollard H, Hoskins W. Labral injuiries of the hip: a review of diagnosis and management. J ManipulativePhysiolTher. 2005; 28(8): 632

- ↑ Anders Troelsen, IngerMechlenburg, John Gelineck, Lars Bolvig, Steffen Jacobsen and KjelSoballe, What is the rol of clinicaltestst and ultrasound in acetabular labral teardiagnostics, Acta Orthopaedica 2009; 80 (3): 314-318

- ↑ Anders Troelsen, IngerMechlenburg, John Gelineck, Lars Bolvig, Steffen Jacobsen and KjelSoballe, What is the rol of clinicaltestst and ultrasound in acetabular labral teardiagnostics, Acta Orthopaedica 2009; 80 (3): 314-318

- ↑ Barbare A. Springer, Norman W. Gill, Brett A. Freedman, Amy E. Ross, Matthew A. Javernick, Kevin P. Murphy, Acetabular labral tears: Diagnosticaccuracy of clinical examination by a physicaltherapist, orthopaedicsurgeon and orthopaedicresidents, North American Journal of SportsPhysicaltherapy, 2009; 4 (1): 38-45

- ↑ McCarthy JC, Noble P, Schunk M, Alusio FV, Wright J, Lee J. Acetabular and labral pathology. In: Early hip disordes. New York: Springer Verlag; 2003

- ↑ . Craig Garrison, Michael T. Osler, Steven B. Singleton, Rehabilitationafterarthroscopiy of anacetabular labral tear, northamericanjournal of sports and physical therapy,2007;2 (4):241-250

- ↑ . Craig Garrison, Michael T. Osler, Steven B. Singleton, Rehabilitationafterarthroscopiy of anacetabular labral tear, northamericanjournal of sports and physical therapy,2007;2 (4):241-250