Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

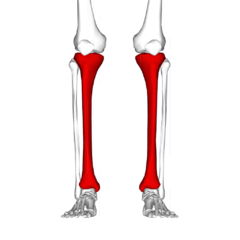

[[File:Tibia - frontal view.png|thumb|Pain generally in the inner and lower 2/3rds of tibia.]] | [[File:Tibia - frontal view.png|thumb|Pain generally in the inner and lower 2/3rds of tibia.|alt=|240x240px]] | ||

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS) is a common overuse injury of the lower extremity. It typically occurs in runners and other athletes that are exposed to intensive weight-bearing activities such as jumpers<ref>Radiopedia Medial tibial stress syndrome Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/medial-tibial-stress-syndrome-1<nowiki/>(accessed 2.6.2022)</ref>. It presents as exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures.<ref name=":9">McClure CJ, Oh R. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. 2019 Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538479/ (accessed 2.6.2022)</ref>. It is provoked on palpation over a length of ≥ 5 consecutive centimetres. <ref name=":0">Winters, M. Medial tibial stress syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and outcome assessment (PhD Academy Award). Br J Sports Med. 2018</ref><ref name=":1">Thacker, S. B., Gilchrist, J., Stroup, D. F., & Kimsey, C. D. The prevention of shin splints in sports: a systematic review of literature. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002; ''34''(1): 32-40.</ref><ref name=":2">Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2848339/pdf/12178_2009_Article_9055.pdf Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options]. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009; ''2''(3): 127-133.</ref> | Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS) is a common overuse injury of the lower extremity. It typically occurs in runners and other athletes that are exposed to intensive weight-bearing activities such as jumpers<ref name=":10">Radiopedia Medial tibial stress syndrome Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/medial-tibial-stress-syndrome-1<nowiki/>(accessed 2.6.2022)</ref>. It presents as exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures.<ref name=":9">McClure CJ, Oh R. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. 2019 Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538479/ (accessed 2.6.2022)</ref>. It is provoked on palpation over a length of ≥ 5 consecutive centimetres. <ref name=":0">Winters, M. Medial tibial stress syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and outcome assessment (PhD Academy Award). Br J Sports Med. 2018</ref><ref name=":1">Thacker, S. B., Gilchrist, J., Stroup, D. F., & Kimsey, C. D. The prevention of shin splints in sports: a systematic review of literature. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002; ''34''(1): 32-40.</ref><ref name=":2">Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2848339/pdf/12178_2009_Article_9055.pdf Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options]. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009; ''2''(3): 127-133.</ref> | ||

It has the layman's moniker of “shin splints.”<ref name=":9" /> | It has the layman's moniker of “shin splints.”<ref name=":9" /> | ||

== Epidemiology == | == Epidemiology == | ||

[[File:Runner surface and shoes.jpg|thumb|Risk factor- quick increase in running volume]] | |||

The incidence of MTSS ranges between 13.6% to 20% in runners and up to 35% in military recruits. In dancers it is present in 20% of the population and up to 35% of the new recruits of runners and dancers will develop it<ref name=":3">Lohrer, H., Malliaropoulos, N., Korakakis, V., & Padhiar, N. Exercise-induced leg pain in athletes: diagnostic, assessment, and management strategies. The Physician and sports medicine. 2018</ref> | The incidence of MTSS ranges between 13.6% to 20% in runners and up to 35% in military recruits. In dancers it is present in 20% of the population and up to 35% of the new recruits of runners and dancers will develop it<ref name=":3">Lohrer, H., Malliaropoulos, N., Korakakis, V., & Padhiar, N. Exercise-induced leg pain in athletes: diagnostic, assessment, and management strategies. The Physician and sports medicine. 2018</ref> | ||

Large increase in loads, volume and high impact exercise can put at risk individuals to MTSS. Risk factors include being a female, previous history of MTSS, high [[Body Mass Index|BMI]], [[Navicular Drop Test|navicular drop]], reduced hip external rotation range of motion, muscle imbalance and inflexibility of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles), muscle weakness of the triceps surae (prone to muscle fatigue leading to altered running mechanics, and strain on the tibia), running on a hard or uneven surface and bad running shoes (like a poor shock absorbing capacity).<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":2" /> <ref name="Broos, 1991">Broos P. Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, 1991. (Level of Evidence: 5)</ref> | Large increase in loads, volume and high impact exercise can put at risk individuals to MTSS. Risk factors include being a female, previous history of MTSS, high [[Body Mass Index|BMI]], [[Navicular Drop Test|navicular drop]], reduced hip external rotation range of motion, muscle imbalance and inflexibility of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles), muscle weakness of the triceps surae (prone to muscle fatigue leading to altered running mechanics, and strain on the tibia), running on a hard or uneven surface and bad running shoes (like a poor shock absorbing capacity).<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":2" /> <ref name="Broos, 1991">Broos P. Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, 1991. (Level of Evidence: 5)</ref> | ||

== Pathophysiology == | |||

The pathophysiologic process resulting in MTSS is related to unrepaired microdamage accumulation in the cortical bone of the distal tibia, however this has not been definitively established. Two current theories are: | |||

# The pain is secondary to inflammation of the periosteum as a result of excessive traction of the tibialis posterior or soleus, supported by bone scintigraphy findings of a broad linear band of increased uptake along the medial tibial periosteum. But a case-controlled ultrasound based study which compared periosteal and tendinous edema of athletes with and without medial tibial stress syndrome found no difference between the groups. | |||

# Bony overload injury, with resultant microdamage and targeted remodeling. A study evaluating tibia biopsy specimens from the painful area of six athletes suffering from medial tibial stress syndrome gave only equivocal support for this theory. Linear microcracks were found in only three specimens and there was no associated repair reaction<ref>Milgrom C, Zloczower E, Fleischmann C, Spitzer E, Landau R, Bader T, Finestone AS. Medial tibial stress fracture diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2021 Jun 1;24(6):526-30. Available:https://sbrate.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Artigo-Andr%C3%A9-Pedrinelli-Ot%C3%A1vio-Assis-COMPLEMENTO-JSAMS_MEDIAL_TIBIAL_STRESS_GUIDELINES.pdf (accessed 2.6.2022)</ref>. | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

| Line 19: | Line 26: | ||

At first the patient only feels pain at the beginning of the workout, often disappearing while exercising, only to return during the cool-down period. When shin splints get worse the pain can remain during exercise and also could be present for hours of days after cessation of the inducing activity.<ref name=":3" /> | At first the patient only feels pain at the beginning of the workout, often disappearing while exercising, only to return during the cool-down period. When shin splints get worse the pain can remain during exercise and also could be present for hours of days after cessation of the inducing activity.<ref name=":3" /> | ||

The most common complication of shin-splints is a stress fracture, which shows itself by tenderness of the anterior tibia.<ref name=":2" /> Neurovascular signs and symptoms are not commonly attributable to MTSS and when present, other pathologies such as chronic | The most common complication of shin-splints is a stress fracture, which shows itself by tenderness of the anterior tibia.<ref name=":2" /> Neurovascular signs and symptoms are not commonly attributable to MTSS and when present, other pathologies such as chronic exertioal compartment syndrome (CECS) or vascular deficiencies should be considered as the source of leg pain.<ref name=":4">The runner´s world editors. Everything you need to know about shin splints. Available from<sup>:</sup> http://www.runnersworld.com/tag/shin-splints. (Accessed 10/12/2018) Level of evidence 5</ref><ref name=":5">Moen, M. H., Tol, J. L., Weir, A., Steunebrink, M., & De Winter, T. C. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Sports medicine. ''2009;'' ''39''(7): 523-546. (Level of evidence 3A)</ref><ref name="Broos, 1991" /> | ||

A "one-leg hop test" is a functional test, that can be used to distinguish between medial tibial stress syndrome and a stress fracture: a patient with medial tibial stress syndrome can hop at least 10 times on the affected leg where a patient with a stress fracture cannot hop without severe pain.<ref name=":10" /> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! colspan="2" |KEY POINTS FOR ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT FOR MTSS<ref name=":3" /> | ! colspan="2" |KEY POINTS FOR ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT FOR MTSS<ref name=":3" /> | ||

| Line 54: | Line 48: | ||

|} | |} | ||

== | == Diagnosis == | ||

Making the diagnosis based on history and physical examination is the most logical approach.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> | Making the diagnosis based on history and physical examination is the most logical approach.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> | ||

# A standardised history include questions on the onset and location of the pain: | # A standardised history include questions on the onset and location of the pain: | ||

| Line 64: | Line 58: | ||

#* If other symptoms not typical of MTSS are present (severe and visible swelling or erythema along the medial border): other leg injury should be considered | #* If other symptoms not typical of MTSS are present (severe and visible swelling or erythema along the medial border): other leg injury should be considered | ||

#* If recognisable pain is present on palpation over 5 cm or more and no atypical symptoms are present, the diagnosis MTSS is confirmed. | #* If recognisable pain is present on palpation over 5 cm or more and no atypical symptoms are present, the diagnosis MTSS is confirmed. | ||

It is important that clinicians be aware that about 1/3 (32%) of the athletes with MTSS have co-existing lower leg injuries<ref name=":3" /> | It is important that clinicians be aware that about 1/3 (32%) of the athletes with MTSS have co-existing lower leg injuries<ref name=":3" /> | ||

| Line 122: | Line 110: | ||

The role of hip internal rotation motion is unclear. Differences between hip muscle performance in MTSS and control subjects might be the effect rather than the cause MIO2 | The role of hip internal rotation motion is unclear. Differences between hip muscle performance in MTSS and control subjects might be the effect rather than the cause MIO2 | ||

'''Acute phase''' | |||

2-6 weeks of rest combined with medication is recommended to improve the symptoms and for a quick and safe return after a period of rest. NSAIDs and Acetaminophen are often used for analgesia. Also cryotherapy with Ice-packs and eventually analgesic gels can be used after exercise for a period of 20 minutes. | 2-6 weeks of rest combined with medication is recommended to improve the symptoms and for a quick and safe return after a period of rest. NSAIDs and Acetaminophen are often used for analgesia. Also cryotherapy with Ice-packs and eventually analgesic gels can be used after exercise for a period of 20 minutes. | ||

There are a number of physical therapy modalities to use in the acute phase but there is no proof that these therapies such as ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, electrical stimulation<ref name=":6" /> would be effective.<ref name=":2" /> A corticoid injection is contraindicated because this can give a worse sense of health. Because the healthy tissue is also treated. A corticoid injection is given to reduce the pain, but only in connection with rest.<ref name="Broos, 1991" /> | * There are a number of physical therapy modalities to use in the acute phase but there is no proof that these therapies such as ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, electrical stimulation<ref name=":6" /> would be effective.<ref name=":2" /> A corticoid injection is contraindicated because this can give a worse sense of health. Because the healthy tissue is also treated. A corticoid injection is given to reduce the pain, but only in connection with rest.<ref name="Broos, 1991" /> | ||

* Prolonged rest is not ideal for an athlete | |||

'''Subacute phase''' | |||

The treatment should aim to modify training conditions and to address eventual biomechanical abnormalities. Change of training conditions could be decreased running distance, intensity and frequency and intensity by 50%. It is advised to avoid hills and uneven surfaces. | The treatment should aim to modify training conditions and to address eventual biomechanical abnormalities. Change of training conditions could be decreased running distance, intensity and frequency and intensity by 50%. It is advised to avoid hills and uneven surfaces. | ||

During the rehabilitation period the patient can do low impact and cross-training exercises (like running on a hydro-gym machine).). After a few weeks athletes may slowly increase training intensity and duration and add sport-specific activities, and hill running to their rehabilitation program as long as they remain pain-free. | * During the rehabilitation period the patient can do low impact and cross-training exercises (like running on a hydro-gym machine).). After a few weeks athletes may slowly increase training intensity and duration and add sport-specific activities, and hill running to their rehabilitation program as long as they remain pain-free. | ||

* A stretching and strengthening (eccentric) calf exercise program can be introduced to prevent muscle fatigue. <ref name=":8" /><ref>Couture C, Karlson K. Tibial stress injuries: decisive diagnosis and treatment of ‘shin splints’. Phys Sportsmed. 2002;30(6):29–36.(Level of Evidence: 3a)</ref><ref name=":7">DeLee J, Drez D, Miller M. DeLee and Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2003:2155–2159.(Level of Evidence: 5)</ref> (Level of Evidence: 3a) (Level of Evidence: 3a) (Level of Evidence: 5). Patients may also benefit from strengthening core hip muscles. Developing core stability with strong abdominal, gluteal, and hip muscles can improve running mechanics and prevent lower-extremity overuse injuries. <ref name=":7" /> | |||

* Proprioceptive balance training is crucial in neuromuscular education. This can be done with a one-legged stand or balance board. Improved proprioception will increase the efficiency of joint and postural-stabilizing muscles and help the body react to running surface incongruities, also key in preventing re-injury.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

* Choossing good shoes with good shock absorption can help to prevent a new or re-injury. Therefore it is important to change the athlete's shoes every 250-500 miles, a distance at which most shoes lose up to 40% of their shock-absorbing capabilities.<br>In case of biomechanical problems of the foot may individuals benefit from orthotics. An over-the-counter orthosis (flexible or semi-rigid) can help with excessive foot pronation and pes planus. A cast or a pneumatic brace can be necessary in severe cases.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

* Manual therapy can be used to control several biomechanical abnormalities of the spine, sacro-illiacal joint and various muscle imbalances. They are often used to prevent relapsing to the old injury. | |||

* There is also acupuncture, ultrasound therapy injections and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy but their efficiency is not yet proved. | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

An algorithmic approach has been established for further differentiating exercise-induced leg pain entities<ref name=":3" />: | |||

# Pain at rest with palpable tenderness indicates bone stress injuries (MTSS and stress fractures), | |||

# No pain at rest with palpable tenderness proposes nerve entrapment syndromes | |||

# No pain at rest with no palpable tenderness makes functional popliteal artery entrapment syndrome and chronic exertional compartment syndrome likely | |||

MTSS may overlap with the diagnosis of deep posterior compartment syndrome but the critical point for differentiation is the longer lasting post-exercise pain when compared with deep posterior chronic exertional compartment syndrome. | |||

Compared with stress fractures, the painful area extends over more than 5 cm on the distal two thirds of the medial tibial border. | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Revision as of 03:02, 2 June 2022

Original Editors - Karsten De Koster

Top Contributors - Karsten De Koster, Claudia Karina, Nick Van Doorsselaer, Alex Palmer, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kenza Mostaqim, Arno Van Hemelryck, Luna Antonis, Kim Jackson, Bieke Bardyn, Sally Ngo, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly, Fitz Van Roy, 127.0.0.1, Claire Knott, Venus Pagare, Chelsea Mclene, Daniele Barilla and Kai A. Sigel

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS) is a common overuse injury of the lower extremity. It typically occurs in runners and other athletes that are exposed to intensive weight-bearing activities such as jumpers[1]. It presents as exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures.[2]. It is provoked on palpation over a length of ≥ 5 consecutive centimetres. [3][4][5]

It has the layman's moniker of “shin splints.”[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of MTSS ranges between 13.6% to 20% in runners and up to 35% in military recruits. In dancers it is present in 20% of the population and up to 35% of the new recruits of runners and dancers will develop it[6]

Large increase in loads, volume and high impact exercise can put at risk individuals to MTSS. Risk factors include being a female, previous history of MTSS, high BMI, navicular drop, reduced hip external rotation range of motion, muscle imbalance and inflexibility of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles), muscle weakness of the triceps surae (prone to muscle fatigue leading to altered running mechanics, and strain on the tibia), running on a hard or uneven surface and bad running shoes (like a poor shock absorbing capacity).[2][5] [7]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiologic process resulting in MTSS is related to unrepaired microdamage accumulation in the cortical bone of the distal tibia, however this has not been definitively established. Two current theories are:

- The pain is secondary to inflammation of the periosteum as a result of excessive traction of the tibialis posterior or soleus, supported by bone scintigraphy findings of a broad linear band of increased uptake along the medial tibial periosteum. But a case-controlled ultrasound based study which compared periosteal and tendinous edema of athletes with and without medial tibial stress syndrome found no difference between the groups.

- Bony overload injury, with resultant microdamage and targeted remodeling. A study evaluating tibia biopsy specimens from the painful area of six athletes suffering from medial tibial stress syndrome gave only equivocal support for this theory. Linear microcracks were found in only three specimens and there was no associated repair reaction[8].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The main symptom is dull pain at the distal two third of the posteromedial tibial border. The pain is non-focal but extends over “at least 5 cm” [6] and is often bilateral[9].It also worsens at each moment of contact.[7] A mild edema in this painful area may also be present and tenderness on palpation is typically present following the inducing activity for up to several days.[6]

At first the patient only feels pain at the beginning of the workout, often disappearing while exercising, only to return during the cool-down period. When shin splints get worse the pain can remain during exercise and also could be present for hours of days after cessation of the inducing activity.[6]

The most common complication of shin-splints is a stress fracture, which shows itself by tenderness of the anterior tibia.[5] Neurovascular signs and symptoms are not commonly attributable to MTSS and when present, other pathologies such as chronic exertioal compartment syndrome (CECS) or vascular deficiencies should be considered as the source of leg pain.[10][11][7]

A "one-leg hop test" is a functional test, that can be used to distinguish between medial tibial stress syndrome and a stress fracture: a patient with medial tibial stress syndrome can hop at least 10 times on the affected leg where a patient with a stress fracture cannot hop without severe pain.[1]

| KEY POINTS FOR ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT FOR MTSS[6] | |

|---|---|

| HISTORY | Increasing pain during exercise related to the medial tibial border in the middle and lower third

Pain persists for hours or days after cessation of activity |

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | Intensive tenderness of the involved medial tibial border

More than 5 cm |

| IMAGING | MRI: Periosteal reaction and edema |

| TREATMENT | Mainly conservative (running retraining, ESWT) |

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Making the diagnosis based on history and physical examination is the most logical approach.[3][4]

- A standardised history include questions on the onset and location of the pain:

- If there is exercise-induced pain along the distal 2/3 of the medial tibial border: MTSS diagnosis is suspected

- The athlete is asked of what aggravated and relieved their pain: If pain is provoked during or after physical activity and reduced with relative rest, MTSS diagnosis is suspected

- The athlete is asked about cramping, burning and pressure-like calf pain and/or pins and needles in the foot (their presence could be signs of chronic exertional compartment syndrome, which could be a concurrent injury or the sole explanation for their pain): If no present, MTSS diagnosis is suspected

- Physical examination If MTSS is suspected after the history: the posteromedial tibial border is palpated and the athletes are asked for the presence of recognisable pain (ie, from painful activities).

- If no pain on palpation is present, or the pain is palpated over less than 5 cm: other lower leg injuries (eg, a stress fracture) has to be considered to be present and the athlete is labelled as not having MTSS

- If other symptoms not typical of MTSS are present (severe and visible swelling or erythema along the medial border): other leg injury should be considered

- If recognisable pain is present on palpation over 5 cm or more and no atypical symptoms are present, the diagnosis MTSS is confirmed.

It is important that clinicians be aware that about 1/3 (32%) of the athletes with MTSS have co-existing lower leg injuries[6]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The MTSS score should be used as a primary outcome measure in MTSS because is valid, reliable and responsive. It measures:[3]

- Pain at rest

- Pain while performing activities of daily living

- Limitations in sporting activities

- Pain while performing sporting activities.

The MTSS score specifically measures pain along the shin and limitations due to shin pain.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Examination demonstrates an intensive tenderness on palpation along the medial tibial border, the anterior tibia, however, is usually nontender. Neurovascular symptoms are usually absent. Different from stress fracture, the pain is not focused to a specific point but covers a variable distance of several centimeters in the distal medial and proximal distal third of the tibia.[6] In the painful area, there is no real muscle origin, but the deep crural fascia is attached to the medial tibial border. From clinical experience, a painful transverse band can frequently be palpated which most probably corresponds to the soleal aponeurosis .Therefore, MTSS is currently hypothesized to originate from tibial bone overload and not from adjacent soft tissue stress[6]

Physicians should carefully evaluate for possible knee abnormalities (especially genu varus or valgus), tibial torsion, femoral anteversion, foot arch abnormalities, or a leg-length discrepancy. Ankle movements and subtalar motion should also be evaluated. Clinicians should also examine for inflexibility and imbalance of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles and weakness of “core muscles”. Core and pelvic muscle stability may be assessed by evaluating patient’s ability to maintain a controlled, level pelvis during a pelvic bridge from the supine position, or a standing single-leg knee bend.

Examining patient’s shoes may reveal generally worn-out shoes or patterns consistent with a leg-length discrepancy or other biomechanical abnormalities.

Abnormal gait patterns should be evaluated with the patient walking and running on a treadmill. [11][12][13][14][15][5] [16][17][18][19][20][21][22]

Management[edit | edit source]

Management of MTSS is conservative, focusing on rest and activity modification with less repetitive, load-bearing exercise. No specific recommendations on the duration of rest required for resolution of symptoms, and it is likely variable depending on the individual.

Other therapies available (with low-quality evidence) include iontophoresis, phonophoresis, ice massage, ultrasound therapy, periosteal pecking, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy. A recent study on naval recruits showed prefabricated orthotics reduced MTSS[2].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Patient education and a graded loading exposure program seem the most logical treatments.[3] Conservative therapy should initially aim to correct functional, gait, and biomechanical overload factors.[6]Recently ‘running retraining’ has been advocated as a promising treatment strategy and graded running programme has been suggested as a gradual tissue-loading intervention.[6]

Prevention of MTSS was investigated in few studies and shock-absorbing insoles, pronation control insoles, and graduated running programs were advocated.[6]

Overstress avoidance is the main preventive measure of MTSS or shin-splints. The main goals of shin-splints treatment are pain relieve and return to pain‑free activities.[23]

For the treatment of shin-splints it’s important to screen the risk factors, this makes it easier to make a diagnosis and to prevent this disease. In the next table you can find them.[24] (Level of Evidence: 1a)

| Intrinsic factors | Extrinsic factors |

| Age Sex Height Weight Body fat Femoral neck anteversion Genu valgus Pes clavus Hyperpronation Joint laxity Aerobic endurance/conditioning Fatigue Strength of and balance between flexors and extensors Flexibility of muscles/joints Sporting skill/coordination Physiological factors |

Sports-related factors Type of sport Exposure (e.g., running on one side of the road) Nature of event (e.g., running on hills) Equipment Shoe/surface interface Venue/supervision Playing surface Safety measures Weather conditions Temperature |

Control of risk factors could be a relevant strategy to initially avoid and treat MTSS: MIO2

- Female gender

- Previous history of MTSS

- Fewer years of running experience

- Orthotic use

- Increased body mass index

- Pronated foot posture (increased navicular drop)

- Increased ankle plantarflexion

- Increased hip external rotation

The role of hip internal rotation motion is unclear. Differences between hip muscle performance in MTSS and control subjects might be the effect rather than the cause MIO2

Acute phase

2-6 weeks of rest combined with medication is recommended to improve the symptoms and for a quick and safe return after a period of rest. NSAIDs and Acetaminophen are often used for analgesia. Also cryotherapy with Ice-packs and eventually analgesic gels can be used after exercise for a period of 20 minutes.

- There are a number of physical therapy modalities to use in the acute phase but there is no proof that these therapies such as ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, electrical stimulation[12] would be effective.[5] A corticoid injection is contraindicated because this can give a worse sense of health. Because the healthy tissue is also treated. A corticoid injection is given to reduce the pain, but only in connection with rest.[7]

- Prolonged rest is not ideal for an athlete

Subacute phase

The treatment should aim to modify training conditions and to address eventual biomechanical abnormalities. Change of training conditions could be decreased running distance, intensity and frequency and intensity by 50%. It is advised to avoid hills and uneven surfaces.

- During the rehabilitation period the patient can do low impact and cross-training exercises (like running on a hydro-gym machine).). After a few weeks athletes may slowly increase training intensity and duration and add sport-specific activities, and hill running to their rehabilitation program as long as they remain pain-free.

- A stretching and strengthening (eccentric) calf exercise program can be introduced to prevent muscle fatigue. [17][25][26] (Level of Evidence: 3a) (Level of Evidence: 3a) (Level of Evidence: 5). Patients may also benefit from strengthening core hip muscles. Developing core stability with strong abdominal, gluteal, and hip muscles can improve running mechanics and prevent lower-extremity overuse injuries. [26]

- Proprioceptive balance training is crucial in neuromuscular education. This can be done with a one-legged stand or balance board. Improved proprioception will increase the efficiency of joint and postural-stabilizing muscles and help the body react to running surface incongruities, also key in preventing re-injury.[26]

- Choossing good shoes with good shock absorption can help to prevent a new or re-injury. Therefore it is important to change the athlete's shoes every 250-500 miles, a distance at which most shoes lose up to 40% of their shock-absorbing capabilities.

In case of biomechanical problems of the foot may individuals benefit from orthotics. An over-the-counter orthosis (flexible or semi-rigid) can help with excessive foot pronation and pes planus. A cast or a pneumatic brace can be necessary in severe cases.[5] - Manual therapy can be used to control several biomechanical abnormalities of the spine, sacro-illiacal joint and various muscle imbalances. They are often used to prevent relapsing to the old injury.

- There is also acupuncture, ultrasound therapy injections and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy but their efficiency is not yet proved.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

An algorithmic approach has been established for further differentiating exercise-induced leg pain entities[6]:

- Pain at rest with palpable tenderness indicates bone stress injuries (MTSS and stress fractures),

- No pain at rest with palpable tenderness proposes nerve entrapment syndromes

- No pain at rest with no palpable tenderness makes functional popliteal artery entrapment syndrome and chronic exertional compartment syndrome likely

MTSS may overlap with the diagnosis of deep posterior compartment syndrome but the critical point for differentiation is the longer lasting post-exercise pain when compared with deep posterior chronic exertional compartment syndrome.

Compared with stress fractures, the painful area extends over more than 5 cm on the distal two thirds of the medial tibial border.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

‘Shin splints’ is a vague term that implicates pain and discomfort in the lower leg, caused by repetitive loading stress. There can be all sorts of causes to this pathology according to different researches. Therefore, a good knowledge of the anatomy is always important, but it’s also important you know the other disorders of the lower leg to rule out other possibilities, which makes it easier to understand what’s going wrong. Also a detailed screening of known’s risk factors, intrinsic as well as extrinsic, to recognize factors that could add to the cause of the condition and address these problems.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radiopedia Medial tibial stress syndrome Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/medial-tibial-stress-syndrome-1(accessed 2.6.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 McClure CJ, Oh R. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. 2019 Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538479/ (accessed 2.6.2022)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Winters, M. Medial tibial stress syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and outcome assessment (PhD Academy Award). Br J Sports Med. 2018

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thacker, S. B., Gilchrist, J., Stroup, D. F., & Kimsey, C. D. The prevention of shin splints in sports: a systematic review of literature. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002; 34(1): 32-40.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Galbraith, R. M., & Lavallee, M. E. Medial tibial stress syndrome: conservative treatment options. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2009; 2(3): 127-133.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Lohrer, H., Malliaropoulos, N., Korakakis, V., & Padhiar, N. Exercise-induced leg pain in athletes: diagnostic, assessment, and management strategies. The Physician and sports medicine. 2018

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Broos P. Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, 1991. (Level of Evidence: 5)

- ↑ Milgrom C, Zloczower E, Fleischmann C, Spitzer E, Landau R, Bader T, Finestone AS. Medial tibial stress fracture diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2021 Jun 1;24(6):526-30. Available:https://sbrate.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Artigo-Andr%C3%A9-Pedrinelli-Ot%C3%A1vio-Assis-COMPLEMENTO-JSAMS_MEDIAL_TIBIAL_STRESS_GUIDELINES.pdf (accessed 2.6.2022)

- ↑ Reid DC. Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone. 1992

- ↑ The runner´s world editors. Everything you need to know about shin splints. Available from: http://www.runnersworld.com/tag/shin-splints. (Accessed 10/12/2018) Level of evidence 5

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moen, M. H., Tol, J. L., Weir, A., Steunebrink, M., & De Winter, T. C. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Sports medicine. 2009; 39(7): 523-546. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Beck B. Tibial stress injuries: an aetiological review for the purposes of guiding management. Sports Medicine. 1998; 26(4):265-279.

- ↑ Kortebein PM, Kaufman KR, Basford JR, Stuart MJ. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(3 Suppl):S27-33.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Wilder R, Seth S. Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(1):55-81. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Fredericson M. Common injuries in runners. Diagnosis, rehabilitation and prevention. Sports Med. 1996;21:49–72. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Strakowski J, Jamil T. Management of common running injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(3):537–552.(Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Dugan S, Weber K. Stress fracture and rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):401–416. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Sommer H, Vallentyne S. Effect of foot posture on the incidence of medial tibial stress syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:800–804. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Niemuth P, Johnson R, Myers M, Thieman T. Hip muscle weakness and overuse injuries in recreational runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(1):14–21. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Greenman P. Principles of manual medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2003;3(11):337–403, 489. . (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Howell J. Effect of counterstrain on stretch reflexes, Hoffmann reflexes, and clinical outcomes in subjects with plantar fasciitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(9):547–556. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Karageanes S. Principles of manual sports medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. 2005: 467–468. Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Alfayez, S. M., Ahmed, M. L., & Alomar, A. Z. A review article of medial tibial stress syndrome. Journal of Musculoskeletal Surgery and Research. 2017; 1(1): 2. (Level of Evidence: 4)

- ↑ Winkelmann, Z. K., Anderson, D., Games, K. E., & Eberman, L. E. Risk Factors for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in Active Individuals: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of athletic training. 2016; 51(12):1049-1052. (Level of Evidence: 1a)

- ↑ Couture C, Karlson K. Tibial stress injuries: decisive diagnosis and treatment of ‘shin splints’. Phys Sportsmed. 2002;30(6):29–36.(Level of Evidence: 3a)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 DeLee J, Drez D, Miller M. DeLee and Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2003:2155–2159.(Level of Evidence: 5)