Odontoid fractures: Difference between revisions

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors ''' | '''Original Editors ''' | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

The odontoid process, also called the dens, is a protuberance of the axis. Fractures can appear because of forces acting on this anatomical structure.<ref>S.K. Demetrios et al. It is time to reconsider the classification of dens fractures: an anatomical approach. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2008;18:189-195 [Level2]</ref | The odontoid process, also called the dens, is a protuberance of the axis. Fractures can appear because of forces acting on this anatomical structure.<ref>S.K. Demetrios et al. It is time to reconsider the classification of dens fractures: an anatomical approach. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2008;18:189-195 [Level2]</ref> | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

| Line 18: | Line 12: | ||

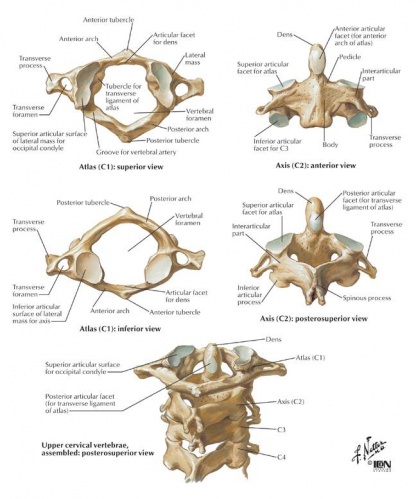

The C2 vertebra or axis is one of three atypical vertebrae. The axis shows a peg-like dens (odontoid process) who projects itself superiorly from its body. The dens lies anterior to the spinal cord and is used as the pivot for the rotation of the head. C1, carrying the cranium, rotates on C2. This rotation takes place on the two superior articular facets. This craniovertebral joint between the atlas and the axis is called, the atlanto-axial joint. The craniovertebral joints distinguish themselves of the others vertebral joints because they do not have intervertebral discs; therefore they possess a wider range of motion than the rest of the vertebral column. The dens of the axis and anterior arch of the atlas are held together by the transverse ligament of the atlas. This ligament prevents anterior displacement of C1 and posterior displacement of C2. If any displacement of this form would occur the spinal cord can be compromised due to the narrowing of the vertebral foramen. Structures that cannot be forgotten are the cervical nerves who pass above and underneath the axis; these nerves are crucial for both the head as the respiratory system (diaphragm).<ref>P. Holck et al. Anatomy of the cervical spine. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2010;130:29-32 [Level 1]</ref><ref>K.L. Moore et al. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Wolters Kluwer 2010 [Level 2]</ref><br> | The C2 vertebra or axis is one of three atypical vertebrae. The axis shows a peg-like dens (odontoid process) who projects itself superiorly from its body. The dens lies anterior to the spinal cord and is used as the pivot for the rotation of the head. C1, carrying the cranium, rotates on C2. This rotation takes place on the two superior articular facets. This craniovertebral joint between the atlas and the axis is called, the atlanto-axial joint. The craniovertebral joints distinguish themselves of the others vertebral joints because they do not have intervertebral discs; therefore they possess a wider range of motion than the rest of the vertebral column. The dens of the axis and anterior arch of the atlas are held together by the transverse ligament of the atlas. This ligament prevents anterior displacement of C1 and posterior displacement of C2. If any displacement of this form would occur the spinal cord can be compromised due to the narrowing of the vertebral foramen. Structures that cannot be forgotten are the cervical nerves who pass above and underneath the axis; these nerves are crucial for both the head as the respiratory system (diaphragm).<ref>P. Holck et al. Anatomy of the cervical spine. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2010;130:29-32 [Level 1]</ref><ref>K.L. Moore et al. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Wolters Kluwer 2010 [Level 2]</ref><br> | ||

[[Image:Dens anatomy.jpg|500x500px]] | [[Image:Dens anatomy.jpg|500x500px]] | ||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

Fractures of the dens represent almost 15% of all cervical spine injuries. It can be seen both in young patients due to a high-energy trauma (e.g. a motor vehicle accident) and in elderly patients due to a low-energy trauma (e.g. a fall). Furthermore, it is the most common fracture of the axis. Looking at the different types, type I occurs very rarely. Type II fractures, on the other hand, are the most frequent. This injury can be associated with various aetiologies. One of the underlying mechanisms is hyperextension of the neck. Other possible causes are a blunt trauma or hyperflexion trauma.<ref name="Khai">S.L. Khai et al. Fractures and dislocations of cervical spine. Orthopaedics and Trauma 2012 [Level 2]</ref><ref name="Torretti">J.A. Torretti et al. Cervical spine trauma. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(4):255-267 [Level 2]</ref><ref name="Pryputniewicz"/><ref name="Greenberg">Greenberg’s Text-atlas of Emergency Medicine [Level 5]</ref | Fractures of the dens represent almost 15% of all cervical spine injuries. It can be seen both in young patients due to a high-energy trauma (e.g. a motor vehicle accident) and in elderly patients due to a low-energy trauma (e.g. a fall). Furthermore, it is the most common fracture of the axis. Looking at the different types, type I occurs very rarely. Type II fractures, on the other hand, are the most frequent. This injury can be associated with various aetiologies. One of the underlying mechanisms is hyperextension of the neck. Other possible causes are a blunt trauma or hyperflexion trauma.<ref name="Khai">S.L. Khai et al. Fractures and dislocations of cervical spine. Orthopaedics and Trauma 2012 [Level 2]</ref><ref name="Torretti">J.A. Torretti et al. Cervical spine trauma. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(4):255-267 [Level 2]</ref><ref name="Pryputniewicz"/><ref name="Greenberg">Greenberg’s Text-atlas of Emergency Medicine [Level 5]</ref> | ||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

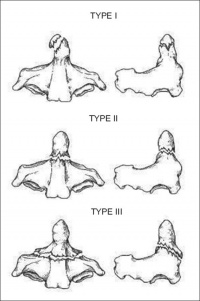

Typically, patients with an odontoid fracture complain about neck pain. Neurological disorders are exceptional, but they can occur when the fractured dens is displaced. Based on the anatomic location of the fracture line, three types can be distinguished. This is called the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification.<ref>J. Jallo et al. Neurotrauma and critical care of the spine. Thieme Medical Publishers et al. 2009 [Level 5]</ref><ref name="Torretti" /> | Typically, patients with an odontoid fracture complain about neck pain. Neurological disorders are exceptional, but they can occur when the fractured dens is displaced. Based on the anatomic location of the fracture line, three types can be distinguished. This is called the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification.<ref>J. Jallo et al. Neurotrauma and critical care of the spine. Thieme Medical Publishers et al. 2009 [Level 5]</ref><ref name="Torretti" /> | ||

* Type I: avulsion fracture of the apex. Stable injuries. | |||

* Type II: fracture through the base of the dens, at the junction of the odontoid base and the body of C2. Often unstable injuries. | |||

* Type III: fracture extends into the body of the axis. Usually stable injuries. | |||

[[ | == Examination == | ||

There is a subdivision of type 2 fractures. A type 2A fracture is minimally displaced and is treated with external immobilisation. A type 2B is displaced and is generally treated with anterior screw fixation. A type 2C is a fracture that extends from antero-inferior to postero-superior and is treated with instrumental fusion of C1 – C2.<br>It is very important to asses any co-morbidities in the diagnostic process because they can affect the treatment. Beside the assessment of the co-morbidities it is very important to subject the patient to a full neurological examination.<ref name="Elgaffy" />[[File:Types_fractures.jpg|301x301px]] | |||

<ref name=" | == Medical Management == | ||

In the literature, mainly 4 treatment strategies are reported, each with distinct pros and contras. Surgically, the two discussed treatments are anterior screw fixation and posterior C1-C2 fusion. Conservatively, the two most reported treatment options are the Halo vest and the rigid cervical collar.<ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop">J.S. Harrop et al., Catastrophic Failure of Conservatively Treated Odontoid Fracture in the Elderly. JHN Journal: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 4: 9-10. [Case Report: Level 5]</ref><ref name="Koivikko">M.P. Koivikko et al., Factors associated with non-union in conservatively-treated type-II fractures of the odontoid process. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 85-B: 1146-1151. [Retrospective analysis: Level 3]</ref><ref name="Pal">D. Pal et al., Type II odontoid fractures in the elderly: an evidence-based narrative review of management. [Review: Level 2-3]</ref><ref name="Pryputniewicz">D.M. Pryputniewicz et al. Axis fractures. Neurosurgery 2010;66:A68-A82 [Level 2]</ref> | |||

== | <sup></sup>The treatment of Type I and Type III odontoid fractures has shown to be effective on a conservative manner.<ref name="Butler">J.S. Butler et al., The long-term functional outcome of type II odontoid fractures managed non-operatively. Eur Spine J (2010) 19: 1635-1642. [Retrospective comparative study: Level 3]</ref><ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Koivikko" /><ref name="Pal" /><sup></sup> The positive outcome of conservative treatment in terms of higher union rate is related to the higher stability of the Type I and III fractures in comparison to Type II fractures.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | ||

The problem lies in the management of Type II odontoid fractures, which are the most common.<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Koivikko" /><ref name="Müller">E. J. Müller et al., Non-rigid immobilisation of odontoid fractures. Eur Spine J (2003) 12 : 522-525. [Retrospective analysis : Level 3]</ref><ref name="Pal" /> Several factors have been reported as being related to the high non-union rates of conservatively treated Type II fractures<ref name="Harrop" />: | |||

* predominance of cortical bone at the base of the axis; bad vascularization of the axis<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | |||

* gapping due the apical ligaments’ traction; | |||

* displacement > 5mm; angulation >10°; | |||

* delayed start of treatment >4 days<ref name="Schoenfeld">A.J. Schoenfeld et al., Type II Odontoid Fractures in the Elderly: Risk of Mortality Based on Intervention. Spine 2011 May 15; 36(11): 879-885. [Retrospective cohort study: Level 3]</ref> | |||

* age >65 years<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy">H. Elgaffy et al., Treatment of Displaced Type II Odontoid Fractures in Elderly Patients. Am J Orthop. 2009; 38(8): 410-416. [Review paper: Level 2-3]</ref><ref name="Harrop" /><sup></sup><ref name="Koivikko" /><ref name="Müller">E. J. Müller et al., Non-rigid immobilisation of odontoid fractures. Eur Spine J (2003) 12 : 522-525. [Retrospective analysis : Level 3]</ref><ref name="Pal" /><ref name="Schoenfeld" /> | |||

Considering which treatment option to go for, co-morbidities should be assessed first,<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy" /><sup></sup><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Müller" /><sup></sup> so that insight could be obtained in possible complications.<ref name="Müller" /> | |||

== | A neurological assessment should also be performed to identify eventual spinal cord injury.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> Although secondary myelopathy as a result of non-union related instability forms a higher risk in elderly<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><sup></sup>, this is a rare complication of non-union which could even take years after follow-up before becoming symptomatic.<ref name="Harrop" /> | ||

There have also been a few case reports about Type III odontoid fractures causing onset of Brown-Séquard syndrome, but this is very rare.<ref name="Wu">Y.T. Wu et al., Brown-Séquard Syndrome caused by type III odontoid fracture: a case report and review of the literature. Spine 2010 Jan 1; 35(1): 27-30. [Case report Level 5; Abstract]</ref> | |||

=== Surgical treatment === | === Surgical treatment === | ||

Surgical indications reported in literature are poly-trauma, neurological deficit, symptomatic non-union (myelopathy) and unstable non-union.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> Patients presenting aforementioned risk factors for non-union are also considered as being indicative for surgery.<ref name="Schoenfeld" /> | |||

< | '''Anterior odontoid screw fixation:''' one or 2 screws are inserted via the anterior-inferior corner of the C2-endplate to stabilise the fracture.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> Reports say that the Type IIB fracture (anterior-superior to posterior-inferior) have the most ideal geometry for this technique.<ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /> | ||

'''Posterior C1-C2 fusion'':''''' different techniques are reported. Gallie wiring technique, Magerl C1-C2 transarticular screw fixation and Harms posterior C1 lateral mass and C2 pars screws.<ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /> | |||

' | |||

''Posterior C1-C2 fusion:'' different techniques are reported. Gallie wiring technique, Magerl C1-C2 transarticular screw fixation and Harms posterior C1 lateral mass and C2 pars screws.<ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" / | |||

Morbid obesity and thoracic kyphosis can interfere with a correct achievement of screw trajectory.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | Morbid obesity and thoracic kyphosis can interfere with a correct achievement of screw trajectory.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | ||

=== Conservative treatment === | === Conservative treatment === | ||

<br>According to an 11 year-retrospective study, non-operative management of stable Type II fractures has shown to have positive long-term functional outcomes in a younger population.<ref name="Koivikko" /> Elderly (>65years<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Koivikko" /><ref name="Müller" /><ref name="Pal" /><ref name="Schoenfeld" /><sup></sup>) showed poor long-term functional outcomes with higher rates of non-union.<ref name="Koivikko | <br>According to an 11 year-retrospective study, non-operative management of stable Type II fractures has shown to have positive long-term functional outcomes in a younger population.<ref name="Koivikko" /> Elderly (>65years<ref name="Butler" /><ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Koivikko" /><ref name="Müller" /><ref name="Pal" /><ref name="Schoenfeld" /><sup></sup>) showed poor long-term functional outcomes with higher rates of non-union.<ref name="Koivikko" /> | ||

< | There’s a big challenge in the fact that non-operative management with external immobilization correlates with high rates of morbidity (complications) and mortality in elderly, especially with the Halo vest.<ref name="Elgaffy" /><ref name="Harrop" /><ref name="Müller" /><sup></sup>. However, in some retrospective studies, the authors claim not to know the exact causes of death, which could be just age-related.<ref name="Müller" /> | ||

Halo vest immobilisation has furthermore been reported to have a non-union rate ranging from 26% to 80%.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | |||

The use of a semi-rigid cervical collar is said to be the treatment of choice in elderly<ref name="Elgaffy" /> (and younger patients with stable fractures)<ref name="Koivikko" />, considering the problems related to Halo vest immobilization and the surgical risks of operative treatment.<ref name="Elgaffy" /> | |||

= | Non-union rates vary up until 77% for cervical collar immobilisation, but when achieving an asymptomatic stable fibrous union is considered a favourable outcome, the union rates raise up to 92%.<ref name="Harrop" /> | ||

Considering the complexity of the treatment of Type II odontoid fractures in elderly and poor total union rates, lowering the outcome expectancy from total union to asymptomatic fibrous union could be taken into consideration.<ref name="Harrop" /> | |||

== | The evidence doesn’t provide any consensus on the treatment strategy for (Type II) odontoid fractures, making an individual approach necessary.<ref name="Harrop" /> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

Physiotherapy management of these conditions is reserved for post- medical management rehabilitation.<br> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 16:18, 9 September 2017

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Sofie Christiaens, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1, Tassignon Bruno, WikiSysop and Karen Wilson

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The odontoid process, also called the dens, is a protuberance of the axis. Fractures can appear because of forces acting on this anatomical structure.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The C2 vertebra or axis is one of three atypical vertebrae. The axis shows a peg-like dens (odontoid process) who projects itself superiorly from its body. The dens lies anterior to the spinal cord and is used as the pivot for the rotation of the head. C1, carrying the cranium, rotates on C2. This rotation takes place on the two superior articular facets. This craniovertebral joint between the atlas and the axis is called, the atlanto-axial joint. The craniovertebral joints distinguish themselves of the others vertebral joints because they do not have intervertebral discs; therefore they possess a wider range of motion than the rest of the vertebral column. The dens of the axis and anterior arch of the atlas are held together by the transverse ligament of the atlas. This ligament prevents anterior displacement of C1 and posterior displacement of C2. If any displacement of this form would occur the spinal cord can be compromised due to the narrowing of the vertebral foramen. Structures that cannot be forgotten are the cervical nerves who pass above and underneath the axis; these nerves are crucial for both the head as the respiratory system (diaphragm).[2][3]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Fractures of the dens represent almost 15% of all cervical spine injuries. It can be seen both in young patients due to a high-energy trauma (e.g. a motor vehicle accident) and in elderly patients due to a low-energy trauma (e.g. a fall). Furthermore, it is the most common fracture of the axis. Looking at the different types, type I occurs very rarely. Type II fractures, on the other hand, are the most frequent. This injury can be associated with various aetiologies. One of the underlying mechanisms is hyperextension of the neck. Other possible causes are a blunt trauma or hyperflexion trauma.[4][5][6][7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typically, patients with an odontoid fracture complain about neck pain. Neurological disorders are exceptional, but they can occur when the fractured dens is displaced. Based on the anatomic location of the fracture line, three types can be distinguished. This is called the Anderson and D’Alonzo classification.[8][5]

- Type I: avulsion fracture of the apex. Stable injuries.

- Type II: fracture through the base of the dens, at the junction of the odontoid base and the body of C2. Often unstable injuries.

- Type III: fracture extends into the body of the axis. Usually stable injuries.

Examination[edit | edit source]

There is a subdivision of type 2 fractures. A type 2A fracture is minimally displaced and is treated with external immobilisation. A type 2B is displaced and is generally treated with anterior screw fixation. A type 2C is a fracture that extends from antero-inferior to postero-superior and is treated with instrumental fusion of C1 – C2.

It is very important to asses any co-morbidities in the diagnostic process because they can affect the treatment. Beside the assessment of the co-morbidities it is very important to subject the patient to a full neurological examination.[9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

In the literature, mainly 4 treatment strategies are reported, each with distinct pros and contras. Surgically, the two discussed treatments are anterior screw fixation and posterior C1-C2 fusion. Conservatively, the two most reported treatment options are the Halo vest and the rigid cervical collar.[9][10][11][12][6]

The treatment of Type I and Type III odontoid fractures has shown to be effective on a conservative manner.[13][9][10][11][12] The positive outcome of conservative treatment in terms of higher union rate is related to the higher stability of the Type I and III fractures in comparison to Type II fractures.[9]

The problem lies in the management of Type II odontoid fractures, which are the most common.[13][9][10][11][14][12] Several factors have been reported as being related to the high non-union rates of conservatively treated Type II fractures[10]:

- predominance of cortical bone at the base of the axis; bad vascularization of the axis[9]

- gapping due the apical ligaments’ traction;

- displacement > 5mm; angulation >10°;

- delayed start of treatment >4 days[15]

- age >65 years[13][9][10][11][14][12][15]

Considering which treatment option to go for, co-morbidities should be assessed first,[13][9][10][10][14] so that insight could be obtained in possible complications.[14]

A neurological assessment should also be performed to identify eventual spinal cord injury.[9] Although secondary myelopathy as a result of non-union related instability forms a higher risk in elderly[13][9][10], this is a rare complication of non-union which could even take years after follow-up before becoming symptomatic.[10]

There have also been a few case reports about Type III odontoid fractures causing onset of Brown-Séquard syndrome, but this is very rare.[16]

Surgical treatment[edit | edit source]

Surgical indications reported in literature are poly-trauma, neurological deficit, symptomatic non-union (myelopathy) and unstable non-union.[9] Patients presenting aforementioned risk factors for non-union are also considered as being indicative for surgery.[15]

Anterior odontoid screw fixation: one or 2 screws are inserted via the anterior-inferior corner of the C2-endplate to stabilise the fracture.[9] Reports say that the Type IIB fracture (anterior-superior to posterior-inferior) have the most ideal geometry for this technique.[9][10]

Posterior C1-C2 fusion: different techniques are reported. Gallie wiring technique, Magerl C1-C2 transarticular screw fixation and Harms posterior C1 lateral mass and C2 pars screws.[9][10]

Morbid obesity and thoracic kyphosis can interfere with a correct achievement of screw trajectory.[9]

Conservative treatment[edit | edit source]

According to an 11 year-retrospective study, non-operative management of stable Type II fractures has shown to have positive long-term functional outcomes in a younger population.[11] Elderly (>65years[13][9][10][11][14][12][15]) showed poor long-term functional outcomes with higher rates of non-union.[11]

There’s a big challenge in the fact that non-operative management with external immobilization correlates with high rates of morbidity (complications) and mortality in elderly, especially with the Halo vest.[9][10][14]. However, in some retrospective studies, the authors claim not to know the exact causes of death, which could be just age-related.[14]

Halo vest immobilisation has furthermore been reported to have a non-union rate ranging from 26% to 80%.[9]

The use of a semi-rigid cervical collar is said to be the treatment of choice in elderly[9] (and younger patients with stable fractures)[11], considering the problems related to Halo vest immobilization and the surgical risks of operative treatment.[9]

Non-union rates vary up until 77% for cervical collar immobilisation, but when achieving an asymptomatic stable fibrous union is considered a favourable outcome, the union rates raise up to 92%.[10]

Considering the complexity of the treatment of Type II odontoid fractures in elderly and poor total union rates, lowering the outcome expectancy from total union to asymptomatic fibrous union could be taken into consideration.[10]

The evidence doesn’t provide any consensus on the treatment strategy for (Type II) odontoid fractures, making an individual approach necessary.[10]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy management of these conditions is reserved for post- medical management rehabilitation.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ S.K. Demetrios et al. It is time to reconsider the classification of dens fractures: an anatomical approach. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2008;18:189-195 [Level2]

- ↑ P. Holck et al. Anatomy of the cervical spine. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2010;130:29-32 [Level 1]

- ↑ K.L. Moore et al. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Wolters Kluwer 2010 [Level 2]

- ↑ S.L. Khai et al. Fractures and dislocations of cervical spine. Orthopaedics and Trauma 2012 [Level 2]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 J.A. Torretti et al. Cervical spine trauma. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(4):255-267 [Level 2]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 D.M. Pryputniewicz et al. Axis fractures. Neurosurgery 2010;66:A68-A82 [Level 2]

- ↑ Greenberg’s Text-atlas of Emergency Medicine [Level 5]

- ↑ J. Jallo et al. Neurotrauma and critical care of the spine. Thieme Medical Publishers et al. 2009 [Level 5]

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 H. Elgaffy et al., Treatment of Displaced Type II Odontoid Fractures in Elderly Patients. Am J Orthop. 2009; 38(8): 410-416. [Review paper: Level 2-3]

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 J.S. Harrop et al., Catastrophic Failure of Conservatively Treated Odontoid Fracture in the Elderly. JHN Journal: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 4: 9-10. [Case Report: Level 5]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 M.P. Koivikko et al., Factors associated with non-union in conservatively-treated type-II fractures of the odontoid process. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 85-B: 1146-1151. [Retrospective analysis: Level 3]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 D. Pal et al., Type II odontoid fractures in the elderly: an evidence-based narrative review of management. [Review: Level 2-3]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 J.S. Butler et al., The long-term functional outcome of type II odontoid fractures managed non-operatively. Eur Spine J (2010) 19: 1635-1642. [Retrospective comparative study: Level 3]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 E. J. Müller et al., Non-rigid immobilisation of odontoid fractures. Eur Spine J (2003) 12 : 522-525. [Retrospective analysis : Level 3]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 A.J. Schoenfeld et al., Type II Odontoid Fractures in the Elderly: Risk of Mortality Based on Intervention. Spine 2011 May 15; 36(11): 879-885. [Retrospective cohort study: Level 3]

- ↑ Y.T. Wu et al., Brown-Séquard Syndrome caused by type III odontoid fracture: a case report and review of the literature. Spine 2010 Jan 1; 35(1): 27-30. [Case report Level 5; Abstract]