Physical Activity in Adolescents with Haemophilia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 256: | Line 256: | ||

A common presentation as a result of injury during sports or equally due to adverse affects associated with inactivity can be joint bleeds. Therefore it is important we are able to manage these appropriately.<br> | A common presentation as a result of injury during sports or equally due to adverse affects associated with inactivity can be joint bleeds. Therefore it is important we are able to manage these appropriately.<br> | ||

During the acute phase, the physiotherapist will attempt to minimise bleeding using the PRICE regime (protection, rest, ice, compression elevation)<ref name="HAEM CARE ">Haemophilia Care. How is Physiotherapy used in Haemophilia care. http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/physiotherapy.html (accessed 10 Oct 2015).</ref>. This will also work in conjunction with factor replacement if necessary.<br> | During the acute phase, the physiotherapist will attempt to minimise bleeding using the PRICE regime (protection, rest, ice, compression elevation)<ref name="HAEM CARE">Haemophilia Care. How is Physiotherapy used in Haemophilia care. http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/physiotherapy.html (accessed 10 Oct 2015).</ref>. This will also work in conjunction with factor replacement if necessary.<br> | ||

Figure 8. PRICE regime | Figure 8. PRICE regime | ||

| Line 262: | Line 262: | ||

[[Image:PRICE2.png|center|500px]]<br> | [[Image:PRICE2.png|center|500px]]<br> | ||

Following the acute phase, the physiotherapy management will focus on regaining full range of movement, muscle strength and reducing pain ( | Following the acute phase, the physiotherapy management will focus on regaining full range of movement, muscle strength and reducing pain<ref>Talking Joints. Let’s talk about physiotherapy for haemophilia patients. https://www.novonordisk.com/content/dam/Denmark/HQ/aboutus/documents/cpih-2015-talkingjoints-brochure-lets-talk-physiotherapy.pdf (accessed 10 Oct 2016).</ref>. As soon as the pain and swelling begin to decrease, the patient should be encouraged to gradually increase the joint range aiming to achieve complete extension. This should be done actively by the patient to encourage muscle contraction, however passive movements may initially be used. It is vital that early active muscle control occurs to prevent the loss of joint movement <ref name="Hermans et al. 2011">Hermans C, De Moerloose P, Fischer K, Holstein K, Klamroth R, Lambert T, Lavigne-Lissalde G, Perez R, Richards M, Dolan G. European Haemophilia Therapy Standardisation Board. Management of acute haemarthrosis in haemophilia A without inhibitors: literature review, European survey and recommendations. Haemophilia 2011;17(3):383-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21323794 (accessed 30 Sept 2015).</ref>;<ref name="Gomis et al. 2009">Gomis M, Querol F, Gallach JE, Gonzalez LM, Aznar JA. Exercise and sport in the treatment of haemophilic patients: a systematic review. Haemophilia 2009;15:1:43-54. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18721151 (accessed 10 Jan 2016).</ref>;<ref name="Mulder 2006">Mulder K. Exercises for people with haemophilia. Montreal: World Federation of Haemophilia. 2006. http://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar_url?url=http%3A%2F%2Fhaemophilia.ie%2FPDF%2FExercise_Guide_med.pdf&amp;hl=en&amp;sa=T&amp;oi=ggp&amp;ct=res&amp;cd=0&amp;ei=PzyiVtjZA8SmmAHg2rKgBw&amp;scisig=AAGBfm1u24jVgQuILSUxSIt96TVBQMLeLg&amp;nossl=1&amp;ws=1366x599 (accessed 22 Jan 2016).</ref>. Rehabilitation involving active exercises and proprioceptive training must then be continued until full pre-bleed joint ROM and function is restored <ref name="Heijnen and Buzzard 2005">Heijnen L, Buzzard BB. The role of physical therapy and rehabilitation in the management of hemophilia in developing countries. Semin Thromb Hemost 2005;31(5):513-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16276459 (accessed 25 Sept 2015).</ref>.<br> | ||

As previously discussed, another key role of the physiotherapist when treating an AWH is promotion of physical activity. Exercise is encouraged as it will improve the child’s fitness, reduce obesity levels, improve muscular strength, and reduce frequency of bleeding episodes and joint deterioration <ref name="Blamey 2010">45.Blamey G, Forsyth A, Zourikian N, Short L, Jankovic N, Kleijn PDE, Flannery T. Comprehensive elements of a physiotherapy exercise program in haemophilia – a global perspective. World Federation of Haemophilia 2010;16:136-145 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02312.x/abstract;jsessionid=BB3B137A0C21342D378A949A977850CA. | As previously discussed, another key role of the physiotherapist when treating an AWH is promotion of physical activity. Exercise is encouraged as it will improve the child’s fitness, reduce obesity levels, improve muscular strength, and reduce frequency of bleeding episodes and joint deterioration <ref name="Blamey 2010">45.Blamey G, Forsyth A, Zourikian N, Short L, Jankovic N, Kleijn PDE, Flannery T. Comprehensive elements of a physiotherapy exercise program in haemophilia – a global perspective. World Federation of Haemophilia 2010;16:136-145 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02312.x/abstract;jsessionid=BB3B137A0C21342D378A949A977850CA.f04t01fckLR(accessed 10 Oct 2015).</ref>. The World Federation of Haemophilia<ref>World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref> advise particular focus towards strengthening, co-ordination, achieving a healthy body weight and improving self-esteem.<br> | ||

(accessed 10 Oct 2015).</ref>. The World Federation of Haemophilia<ref>World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref> advise particular focus towards strengthening, co-ordination, achieving a healthy body weight and improving self-esteem.<br> | |||

As well as the physical aspects concerned, a major aspect of physiotherapy management focuses on education and advice. This is discussed in detail within the following section.<br> | As well as the physical aspects concerned, a major aspect of physiotherapy management focuses on education and advice. This is discussed in detail within the following section.<br> | ||

| Line 283: | Line 282: | ||

Depending on the severity of the condition, as the physiotherapist you must then advise the patient that high contact and collision sports such as ice hockey, rugby, boxing, and wrestling are usually not advised. You can then attempt to encourage non-contact sports such as swimming, walking, cycling, golf, archery, badminton, rowing and sailing <ref name="WFH guidelines">World Federation of Hemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2012;2:6-73. 2012. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>.<br> | Depending on the severity of the condition, as the physiotherapist you must then advise the patient that high contact and collision sports such as ice hockey, rugby, boxing, and wrestling are usually not advised. You can then attempt to encourage non-contact sports such as swimming, walking, cycling, golf, archery, badminton, rowing and sailing <ref name="WFH guidelines">World Federation of Hemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2012;2:6-73. 2012. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>.<br> | ||

You must work in conjunction with the medical team when advising timing of prophylaxis that is appropriate to their chosen sport or activity<ref name="McGee">McGee S et al. Organized sports participation and the association with injury in paediatric patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2015;21(4):538-542. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2786948/ (accessed 15 Nov 2015).</ref>;<ref name="WFH GUIDELINES">World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>. It may also be necessary, where appropriate, to educate and encourage the use of protective equipment e.g if patient has a target joint, or does not take prophylaxis prior to activity <ref name="Philpott et al. 2010">Philpott J, Houghton K, Luke A. Physical activity recommendations for children with specific chronic health conditions: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hemophilia, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Paediatrics &amp; Child Health 2010;15(4):213-218. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2866314/ fckLR(accessed 6 Oct 2015).</ref>. Protective equipment is discussed in detail later in the module.<br> | You must work in conjunction with the medical team when advising timing of prophylaxis that is appropriate to their chosen sport or activity<ref name="McGee">McGee S et al. Organized sports participation and the association with injury in paediatric patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2015;21(4):538-542. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2786948/ (accessed 15 Nov 2015).</ref>;<ref name="WFH GUIDELINES">World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>. It may also be necessary, where appropriate, to educate and encourage the use of protective equipment e.g if patient has a target joint, or does not take prophylaxis prior to activity <ref name="Philpott et al. 2010">Philpott J, Houghton K, Luke A. Physical activity recommendations for children with specific chronic health conditions: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hemophilia, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Paediatrics &amp;amp; Child Health 2010;15(4):213-218. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2866314/ fckLR(accessed 6 Oct 2015).</ref>. Protective equipment is discussed in detail later in the module.<br> | ||

As the physiotherapist you may also be involved in educating school personnel regarding suitable activities for the child, immediate care in case of a bleed, and modifications in activities that may be needed following bleeds<ref name="WFH GUIDELINES">World Federation of Haemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>. <br><br> | As the physiotherapist you may also be involved in educating school personnel regarding suitable activities for the child, immediate care in case of a bleed, and modifications in activities that may be needed following bleeds<ref name="WFH GUIDELINES">World Federation of Haemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).</ref>. <br><br> | ||

Revision as of 18:40, 28 January 2016

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Caitlin MacRae, Hazel Burt, Alex Leishman, Chloe Allan, Kim Jackson, Steven flett, Rucha Gadgil, Admin, Jane Hislop, Michelle Lee, Tarina van der Stockt and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Welcome to this online wiki resource which will focus on ‘The Role of a Physiotherapist in Promotion and Management of Physical Activity in Adolescents with Haemophilia.’ This wiki has been designed as a learning resource for final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified physiotherapists. It is an online self-study module and should take approximately 10 hours to complete.

Before exploring this topic it is important to clearly define the difference between physical activity and exercise, as they will be used synonymously throughout the module.

Physical activity is defined as “as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” [1].

Exercise is a subsection of physical activity, involving planned or structured activity which aims to improve or maintain physical fitness [2].

We hope you find this resource useful and informative.

Aims and Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

The aims of this wiki are as follows:

- To present a learning resource for final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified graduates which aims to develop their knowledge and understanding of the management of adolescents with haemophilia.

- To introduce final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified graduates to the skills, competencies and resources which can be utilised within their clinical practice in order to offer more effective and comprehensive management of adolescents with haemophilia.

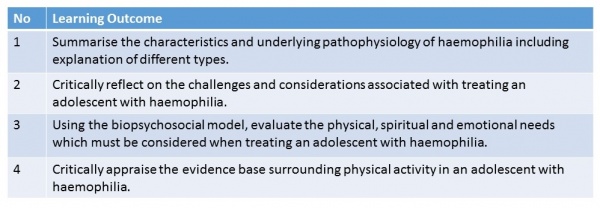

Learning Outcomes:

The following learning outcomes have been constructed using the levels determined by Bloom’s Taxonomy to facilitate learning and development[3]. Through completion of this module and related tasks, final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified physiotherapy graduates will be able to:

Table 1. Learning Outcomes

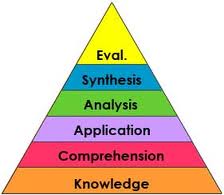

Blooms Taxonomy, shown below, demonstrates a hierarchy of learning. This wiki approaches learning and related activities based on this model with particular focus towards the upper and more advanced levels, involving evaluation and sysnthesis of information. The identified learning aims have been constructed to suit this learning theory.

Figure 1. Blooms Taxonomy

Why is there a need for this Physiopedia page?[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapists role in treating and managing adolescents with haemophilia (AWH) is extremely important, and recent developments within this profession have increased its value [4]. One of the key interventions involved in its treatment is the promotion of physical activity [5].

As physiotherapists, we have an obligation and responsibility to actively promote physical activity in this population, as well as educating the individuals correctly in self-management of their life-long condition. This enables the individual to maximise their quality of life [6]. It is therefore essential for us to have a deep understanding of this condition and the effects and benefits of physical activity and exercise.

How this Wiki relates to the Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF)

[edit | edit source]

The Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF)[7] has been designed by the NHS to demonstrate the necessary knowledge and skill required by staff to deliver high quality services. It includes six core competencies targeting key areas appropriate to each pay band.

Working through this online module will help to contribute to the following learning descriptors needed to meet the criterion for qualification as a band 5 physiotherapist. Although the module will not cover every level indicator, areas of the KSF which have been briefly explored will be detailed below:

Communication

b) improves the effectiveness of communication through the use of communication skills

c) constructively manages barriers to effective communication

e) communicates in a manner that is consistent with relevant legislation, policies and procedures

Personal and People Development

c) takes responsibility for own personal development and takes an active part in learning opportunities

f) offers information to others when it will help their development and/or help them meet work demands

Quality

a) acts consistently with legislation, policies, procedures and other quality approaches and encourages others to do so

c) works as an effective and responsible team member

Assessment and Treatment Planning

a) evaluates relevant information to plan the range and sequence of assessment required and determines:

- the specific activities to be undertaken

- the risks to be managed

- the urgency with which assessments are needed

b) selects appropriate assessment approaches, methods, techniques and equipment, in line with

- individual needs and characteristics

- evidence of effectiveness

- the resources available

d) prepares for, carries out and monitors assessments in line with evidence based practice, and legislation, policies and procedures and/or established protocols / established theories and models

those concerned

h) determines and records diagnosis and treatment plans according to agreed protocols / pathways / models and that are:

- consistent with the outcomes of the assessment

- consistent with the individual’s wishes and views

- include communications with other professions and agencies

- involve other practitioners and agencies when this is necessary to meet people’s health and wellbeing needs and risks

- are consistent with the resources available

- note people’s wishes and needs that it was not possible to meet

i) monitors and reviews the implementation of treatment plans and makes changes within agreed protocols / pathways / models for clinical effectiveness and to meet people’s needs and views

| The following link leads to the Knowledge and Skill Framework Guidance for further information. http://www.ksf.scot.nhs.uk |

[edit | edit source]

Figure 2.

The wiki is organised under the following three main sections:

- Background of Haemophilia

- The Role of the Physiotherapist

- Benefits of Physical Activity

How long you should spend working through each section:

1. 1 hour and 30 minutes

2. 4 hours and 30 minutes

3. 4 hours

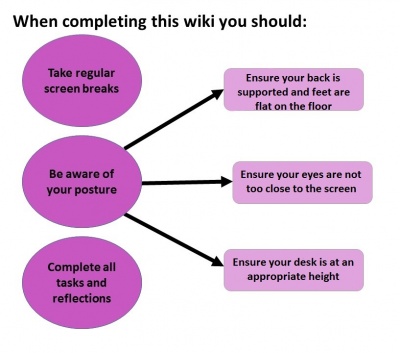

Throughout this learning resource, various tasks, activites and additional reading have been provided to engage the learner. Examples of how these will be laid out are detailed below.

Table 2. Learning activities

|

Links to additional reading will follow this banner,

however this is optional in order to stay within the 10 hours. Please use these if you have further interest in the subject. | |

These activities have been developed to suit different learning styles. Learning styles are common and unique ways in which people learn. The four styles considered are; visual, auditory, reading and writing or kinesthetic learners [8]. If you are unsure of your learning style, please refer to the following link and undertake the VARK Learning Questionnaire.

Background[edit | edit source]

This chapter will offer a brief understanding of haemophilia including pathophysiology, incidence, prevalence, classification, severities and medical management. The role of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) in treating an adolescent with this condition will also be briefly discussed.

The learning outcome to be addressed in this section is:

1. Summarise the characteristics and underlying pathophysiology of haemophilia including explanation of different types.

Definitions, Incidence and Prevelance

[edit | edit source]

Haemophilia is a rare inherited blood disorder where blood in the body has an inability to produce sufficient clotting factor, a protein which controls bleeding [9]. This lack of clotting factor can lead to severe and prolonged bleeds within the body which may cause permanent damage to site of haemorrhage and surrounding tissues[10]. There are an estimated 6000 people living in the United Kingdom with Haemophilia. This condition mainly affects males and is carried genetically through a gene which is passed to child, from parent through the X chromosome [11]

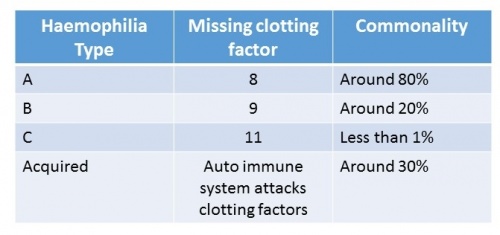

There are four main types of haemophilia. The table below shows the missing clotting factor and commonality for each type:

Table 3. Haemophilia type and factor deficiency and prevalence

Haemophilia A is the most common type. This is where the individual will either have low levels of clotting factor eight or it is completely missing. This type of haemophilia affects around 80% of the haemophilic population[12].

Haemophilia B is less common. This is where clotting factor nine is either very low or is missing from the blood. Around 20% of PWH will have this type[13].

Haemophilia C was first recognized in 1953. This is ten times rarer than type A and differs from both A and B as it can present in both genders. However, this is extremely rare and can only happen when the mother and father are both carriers of the gene [14]. The individuals will have low levels of clotting factor eleven or this will be completed absent.

Acquired Haemophilia is extremely rare. This type is not inherited in the same way as it is an auto-immune disorder. This is where the bodys immune system attacks the clotting factors. This condition can also affect males and females [15].

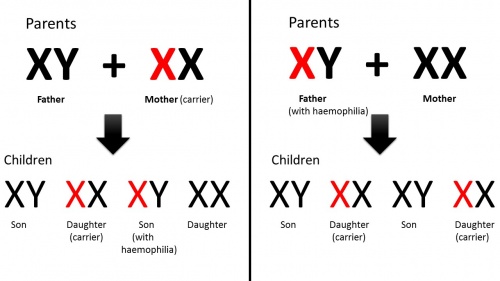

The figure below demonstrates how haemophilia is passed on genetically:

Figure 3. Haemophilia Genetics

As shown above, when the female is the carrier and the father is unaffected, the son will possess a 50% chance of inheriting the condition. There is a 50% chance the daughter will be a carrier of the gene but will not inherit the condition[16].

When the male suffers from haemophilia and the mother is unaffected, none of the sons will inherit the condition. All daughters will carry the gene but will not be affected[16].

If the father has haemophilia and the mother is a carrier, there is a 25% chance that the daughter and son may have haemophilia. This is the only way the female can inherit the condition, however it is extremely rare.

Classifications and Severities[edit | edit source]

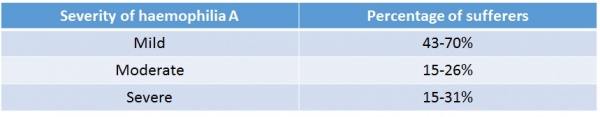

The table below catagorises the severities of haemophilia into mild, moderate and severe, showing the percentage of sufferers in each category [17].

Table 4. Severity occurance

Like other disorders, haemophilia can affect individuals to varying degrees. The symptoms can be mild, moderate or severe, depending on the level of clotting factor present[18].

In mild haemophilia the individual will have between 4% - 49% factor in their blood. Around 43-70% of the haemophilic population are considered mildly affected[19]. Symptoms for mild haemophilia can be non-existent, although may include prolonged bleeding following serious injury, trauma or surgery. In many cases, haemophilia will not be diagnosed until there is excessive bleeding following injury or surgery. In some cases it may not even be discovered until adulthood.

Moderate haemophilic sufferers possess between 1% and 5% of factor level in their blood. 15-26% of AWH are considered moderate[19]. Those with this type are likely to suffer prolonged bleeding following injury and may have occasional spontaneous bleeding episodes.

Severe haemophilia will affect an individual to a greater extent. Those with severe haemophilia will have a factor level between 0% and 1%. This accounts for the other 15-31% of the haemophilia population[20]. They willl experience excessive bleeding following even slight injuries and are also highly likely to have spontaneous bleeding episodes into joints and surrounding muscles[21]. This internal bleeding is particularly dangerous as suffers may be unaware when it is occurring. If untreated it can lead to permanent joint deterioration and arthritis over time.

The link below provides brief facts and figures on haemophilia: http://www.novonordisk.com/content/dam/Denmark/HQ/aboutus/documents/ch-facts-and-figures-poster.pdf |

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

The medical management of haemophilia typically involves two treatment methods, ‘on demand’ or prophylactic. Haemophilia Care explains how treatment involves replacing the deficient clotting factor (VIII for haemophilia A and IX for haemophilia B) through intravenous injection[22].

On demand treatment is administered immediately following a bleed and is most commonly used in mild or moderate cases. It provides the advantage of not having to infuse regularly, however if there is a delay in ‘on demand’ treatment following a bleed then there is potential for damage to occur.

Prophylactic is administered regularly as a method of preventative management and is most commonly used in those with severe haemophilia. The ultimate goal of prophylaxis treatment is to reduce the deficiency of factor VII or factor IX [23], therefore reducing the risk of spontaneous bleeds. It also aims to reduce the severity of the condition [24]. Khoriaty et al explains how clotting factors are infused by the patient themselves on a constant basis around three times a week in the case of severe haemophilia A (factor VIII), and twice a week in severe haemophilia B (factor IX)[25]. Johannes Oldenburg recognises prophylaxis treatment as the optimal treatment for patients with severe haemophilia [26].

| For more information on the medical management of haemophilia please visit the following link WFH Guidelines for the management of haemophilia Pages 12-14. |

MDT Involvement

[edit | edit source]

Before continuing onto this section complete the task below.

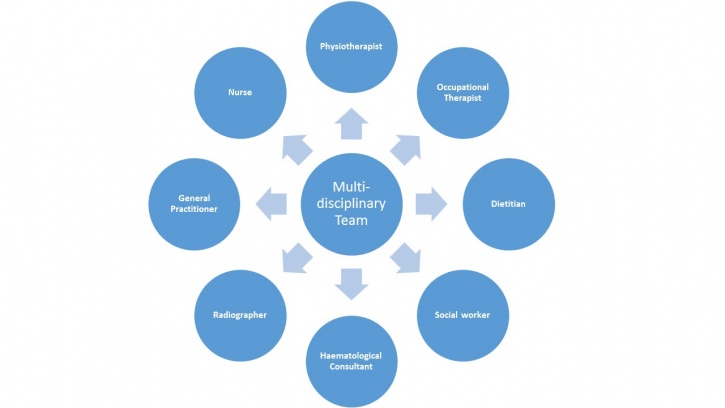

Despite recent development in management of the condition, PWH still require comprehensive multidisciplinary care throughout all stages of their life [27]. A multidisciplinary team involves a range of professionals who collaborate together to structure a treatment plan for an individual, aiming to achieve high quality patient-centered care [28].

The collaboration of all professionals allows a holistic approach to be considered which takes into account the individual’s physical, social, emotional, cultural and spiritual needs [29]. This is especially important during transition from childhood into adulthood which can cause additional stress for those with chronic disorders. Therefore during this time the need for the MDT to work together is essential [27]. This may mean referring the patient to another team member to allow high quality treatment, specific to the patients needs.

Figure 4. mindmap of MDT involved with AWH

Quiz

[edit | edit source]

Having read the content of this section please follow this link to a quiz on the background of haemophilia . This should take approximately 5 minutes to complete. Please check your answers in the answers section at the end of the wiki.

The Role of The Physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

This section of the wiki will examine the role of the physiotherapist including; assessment, management, education, physical activity promotion, considerations, personal protective equipment and how to approach a conversation regarding physical activity.

The learning outcome to be addressed in this section are:

2. Critically reflect on challenges and considerations associated with treating an adolescent with haemophilia.

Assessment

[edit | edit source]

When assessing a patients condition or evaluating success of interventions it is often beneficial for the physiotherapist to use a standardised outcome measures. These offer an objective measure which helps to monitor change in a patients symptoms[30].

Symptoms of a joint bleed may include swollen and hot joints, pain in the area and stiffness when mobilising. Many patients have described the overall feeling as an 'aura' surrounding the joint[31]. The image below shows severe swelling in the left knee during a joint bleed:

Figure 5. Swelling in a knee joint bleed

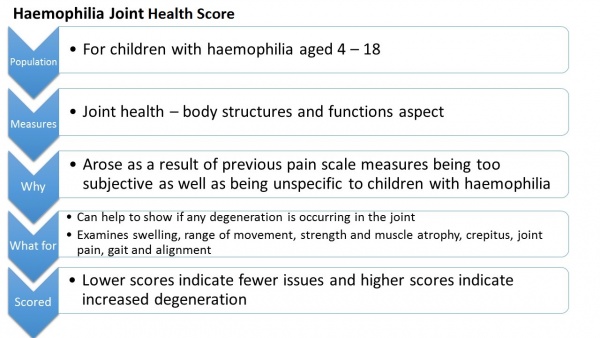

The Haemophilia Joint Health Score [32] is designed for physiotherapists and recommended for use by professionals specialised in haemophilia treatment. The outcome measure takes approximately 45 – 60 minutes to complete and is designed specifically for children with haemophilia. It examines the condition of a joint affected by a bleed and can be used to demonstrate the degeneration of a joint over time.

Figure 6. Haemophilia Joint Health Score characteristics

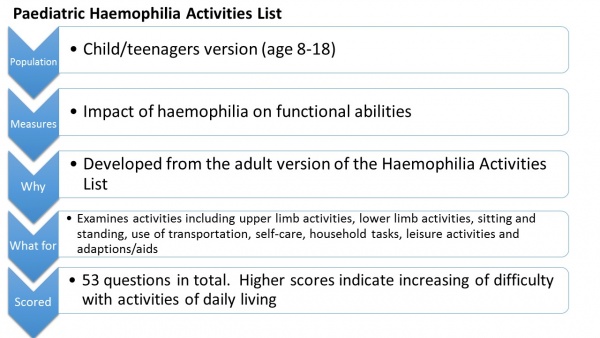

The Paediatric Haemophilia Activities List’ is another outcome measure used for individuals with haemophilia. Adolescents will complete the child/teenager version explaining to what extent their haemophilia impacts upon their daily activities The questionnaire can then be used by healthcare professionals involved in their care[33].

Figure 7. Paediatric Haemophilia Activities List characteristics

Although outcome measures exist for the assessment of children with haemophilia many of these have limited validity and reliability[34]. Physiotherapists play a key role in assessing the joints affected by haemophilia, however it is also helpful for physiotherapists to be aware of other existing measures avialable in order to rehabilitate a patient appropriately.

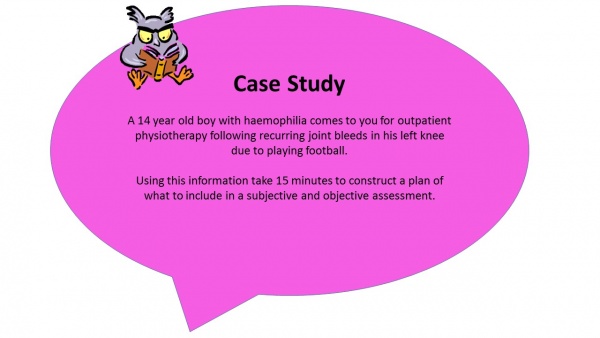

Before continuing on to physiotherapy management take some time to complete the case study below, based on what you have read and using your own knowledge:

After completing your own plan see the answers section at the end of the wiki for our plan of assessment.

Management

[edit | edit source]

The main role of the physiotherapist in treatment of AWH involves management of impairments from a musculoskeletal perspective, aiming to restore and improve function. Some of these include: haemarthoses, synovitis, joint contractures, haemotomas and haemophilic arthropathys[35].

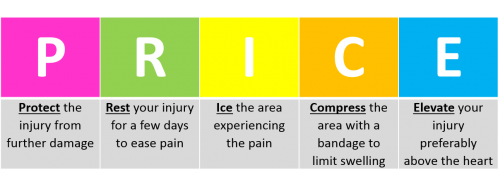

A common presentation as a result of injury during sports or equally due to adverse affects associated with inactivity can be joint bleeds. Therefore it is important we are able to manage these appropriately.

During the acute phase, the physiotherapist will attempt to minimise bleeding using the PRICE regime (protection, rest, ice, compression elevation)[36]. This will also work in conjunction with factor replacement if necessary.

Figure 8. PRICE regime

Following the acute phase, the physiotherapy management will focus on regaining full range of movement, muscle strength and reducing pain[37]. As soon as the pain and swelling begin to decrease, the patient should be encouraged to gradually increase the joint range aiming to achieve complete extension. This should be done actively by the patient to encourage muscle contraction, however passive movements may initially be used. It is vital that early active muscle control occurs to prevent the loss of joint movement [38];[39];[40]. Rehabilitation involving active exercises and proprioceptive training must then be continued until full pre-bleed joint ROM and function is restored [41].

As previously discussed, another key role of the physiotherapist when treating an AWH is promotion of physical activity. Exercise is encouraged as it will improve the child’s fitness, reduce obesity levels, improve muscular strength, and reduce frequency of bleeding episodes and joint deterioration [42]. The World Federation of Haemophilia[43] advise particular focus towards strengthening, co-ordination, achieving a healthy body weight and improving self-esteem.

As well as the physical aspects concerned, a major aspect of physiotherapy management focuses on education and advice. This is discussed in detail within the following section.

Education

[edit | edit source]

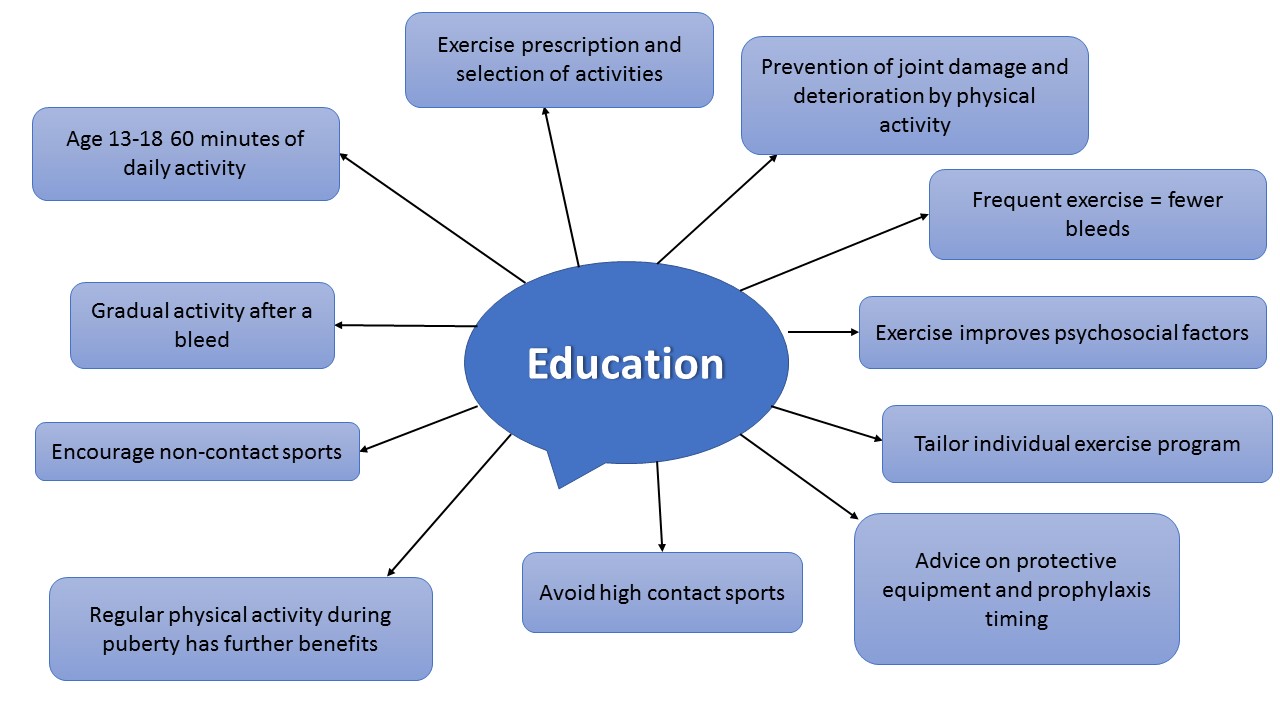

Below is a mind map which summarises key points regarding the advice that should be given to patients regarding physical activity.

Figure 9. Education for AWH from a physiotherapist

The physiotherapist has a crucial role in educating patients regarding physical activity, exercise prescription and selecting particular activities[44].

It is important to ensure patients, relatives and peers are made aware of the positive impacts of physical activity, helping to prevent joint damage and functional impairment[45]. Also, individuals who exercise frequently actually experience fewer bleeds[46].

You should inform patients that just as with healthy individuals, exercise also improves psychosocial wellbeing[47]. It is also important to stress the added benefits of physical activity during puberty in adolescents. Regular physical activity during puberty, enhances lean tissue mass, fitness and strength and decreases fat mass[48].

Depending on the severity of the condition, as the physiotherapist you must then advise the patient that high contact and collision sports such as ice hockey, rugby, boxing, and wrestling are usually not advised. You can then attempt to encourage non-contact sports such as swimming, walking, cycling, golf, archery, badminton, rowing and sailing [49].

You must work in conjunction with the medical team when advising timing of prophylaxis that is appropriate to their chosen sport or activity[50];[51]. It may also be necessary, where appropriate, to educate and encourage the use of protective equipment e.g if patient has a target joint, or does not take prophylaxis prior to activity [52]. Protective equipment is discussed in detail later in the module.

As the physiotherapist you may also be involved in educating school personnel regarding suitable activities for the child, immediate care in case of a bleed, and modifications in activities that may be needed following bleeds[51].

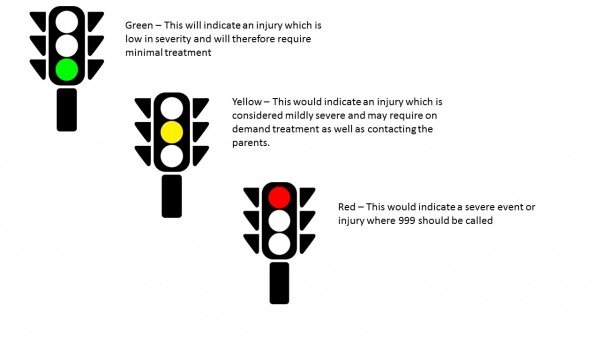

Some parents have found a traffic light coding system beneficial to inform teachers at school of the appropriate actions to take in event of specific injuries or bleed. This is also alluded to in the “get fit and active” video later in the module.

Figure 10. Use of a traffic light system

| • Symptoms of a joint bleed: swollen and hot joints, pain and stiffness • ‘The Haemophilia Joint Health Score’ and ‘The Paediatric Haemophilia Activities List’ are both effective outcome measures for AWH. • Physiotherapists key role - Assessing the joints affected by haemophilia • PRICE regime is important in the acute phase of a bleed • Physiotherapy goals focus on regaining full range of movement, muscle strength and reducing pain after a bleed • 60 minutes of daily activity advised for 13-18 year olds • Advice on protective equipment and use of prophylaxis important |

Physical Activity Promotion

[edit | edit source]

It is already known that physical activity in this population is reduced compared to healthy age-matched peers. The Kings Fund[53] acknowledge health behaviour patterns to impact an individual's overall health by as much as 40%, when compared to healthcare which contributes only 10%. Therefore as Physiotherapists our role in health and activity promotion is crucial in order to influence positive behavioural change to impact upon health[54].

Health promotion involves supporting people to gain control and responsibility over improving their own health. It extends beyond focusing on individual behaviour and includes a variety of social and environmental interventions[55].

The Corporate Policy and Strategy Committee have introduced a Physical Activity for Health Pledge which the NHS is engaging with. This pledge involves ensuring primary care staff have the necessary skills and resources available to assess physical activity levels. It also ensures they offer education detailing recommended minimum requirements for physical activity, brief advice and intervention, along with increasing awareness of available community resources. Unpublished data from NHS Health Scotland reveals only 13% of primary care practitioners are presently aware of the recommended weekly activity levels [56]. It can therefore be assumed this is not currently being promoted effectively.

The following video "23 and a 1/2 hours" strongly promotes physical activity for 30 minutes of your day. Although not specific to the haemophilic population, however the take home message can be followed for AWH as the physical activity benefits are not changed or exhaustive.

Although various studies have described the benefits of engaging in physical activity for people with haemophilia (PWH), results from research conducted in the USA among adolescent haemophilia patients have demonstrated a lack of knowledge concerning the role of physical activity in managing their condition[57]. Whilst it is recognised this information is important, this study has not been conducted in the UK. This suggests that more work must be done to promote physical activity and emphasise its positive role in enhancing the lives of PWH [58].

Physical activity promotion for health exists worldwide [59]. The benefits of such in the general population are widely known, providing health improvements along with the potential for enhancing disease outcomes[60]. National and international guideliness set out clear recommendations on the physical activity levels required to promote health[61]. Although many studies have reported the benefits of participation in physical activity for PWH, researchers in the USA have identified a lack of knowledge among young haemophilia patients (aged 13–18 years) as to the role of exercise in the management of their condition.

The promotion of exercise in AWH is of particular importance due to recent advances in care over the past 40 years [62]. This has seen changes in exercise prescription; as is it now believed to be a crucial modality and understood it will not attribute to bleeds, as previously believed[63].

Considerations

[edit | edit source]

As the physiotherapists it is vital to be aware of risks and considerations when advising patients to participate in physical activity.

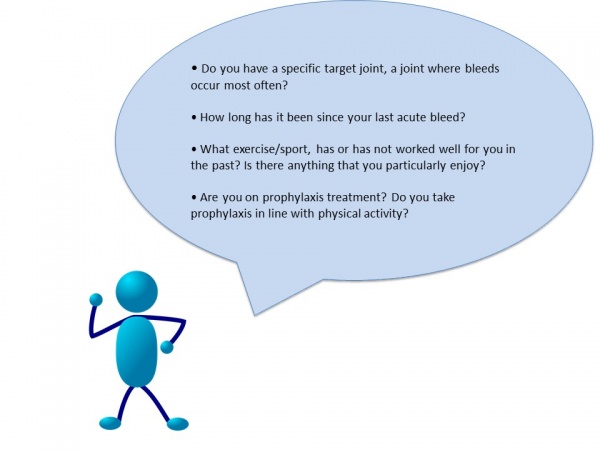

When discussing forms of exercise with the patient, the following information is essential to obtain from your patient;

Figure 11. Questions to ask the patient before treatment:

Knowing whether patients have target joint bleeds allows the physiotherapist to adapt and alter your advice and treatment plan. This will allow you to discuss the use of protective equipment for the target joint, or if there are any other activities which may reduce the risk of contact involving that specific joint.

As discussed previously, it is important to know when the patient’s last acute bleed was and where. Activity must be gradually re-introduced following a bleed to minimise the chance of it reoccurring[64].

It is important to discuss with the patient what exercises they enjoy. This way it is much more likely you will be able to actively promote activity.

Appropriate timing of prophylaxis treatment surrounding physical activity is critical when striving to prevent bleeds. Prophylaxis should be individualised and taken to coincide with exercise. The aim being the factor will be at its peak during the period of activity[65]. This will minimise the risk or potential for bleeds[66]. As discussed previously, you must be aware of this and communicate with the patient’s medical team regarding best advice.

Exercising with inhibitors

[edit | edit source]

Approximately 30% of patients with haemophilia will develop an immune response to medications used to treat the condition. If this occurs an alternative treatment may be necessary to manage bleeds. Immune tolerance therapy is introduced which aims to help the individual become accustomed to the factor[67].

Individuals with inhibitors may initially be apprehensive towards engaging in activity and exercise and physical condition can rapidly decline. A program consisting of active range of motion, isometric and isotonic strengthening, along with balance exercises can facilitate function and help to maintain independence[68].

Guidelines and Recommendations[edit | edit source]

It is important to note that the recommended guidelines for physical activity in children with haemophilia are the same as those advised for healthy individuals. Government issued guidelines exist for children and young people aged 4 – 18. These guidelines state that this age group should be participating in 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity each day. Vigorous activity, which strengthens muscle and bone, should take place at least 3 times a week (Physical Activity Guidelines for children and Young People 2011).

The World Haemophilia Federation[69] has released updated guidelines for the management of people with haemophilia:

- The primary aim of management is to prevent and treat bleeds

- Comprehensive care aims to promote health physically and psychosocially, as well as improving quality of life and reducing morbidity and mortality. Physiotherapists may play a more significant role in this aspect compared to managing the more acute phase of a bleed. Physiotherapy involvement contributes to both the prevention and treatment of bleeds.

- Children and adolescents should be seen every 6 months by a physiotherapist for assessment and management planning

- Physiotherapy has a main role in promoting physical activity: to promote fitness, neuromuscular development, strengthening, coordination, functioning, weight management and self esteem

- Weight bearing activities should be encouraged to encourage bone mineral accrural

- The development of a physical activity plan should be tailored to individuals preference, abilities and severity of condition

- Non-contact sports will be encouraged – i.e. swimming, walking, golf, badminton, cycling, table tennis

- Contact sports and high velocity sports are strongly discouraged due to the risk of a fatal bleed – i.e. rugby, boxing, wrestling, racing, skiing

- Target joints can be protected using braces or splints during activities

- Following a bleed the activity should be reintroduced gradually to minimise the risk of re-bleeding

- Adjunctive management is also vital to physiotherapy. This means activity should be undertaken in conjunction with factor replacement. Physiotherapy can also help reduce the amount of factor necessary.

- In the acute phase, PRICE will be used by the physiotherapist

- Following this, rehabilitation is required to restore function

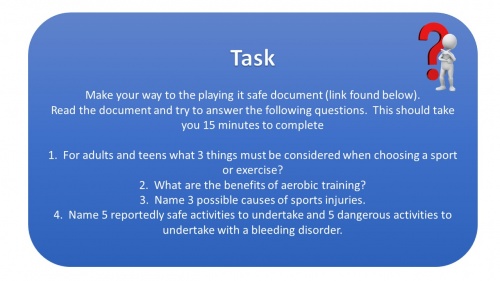

"Playing it Safe"[70] is an online document which provides recommendations and advice regarding partaking in sports and exercise if when suffering with a bleeding disorder.

This document offers recommendations on the safest activities to participate in and gives advice on the sports and exercises with the highest risk of injury.

For adolescents, when considering which activities to take part in, it is important to consider current body condition, history of bleeding and joint condition.

It is also proven the more physically active you were through childhood the easier it will be to remain active in teens and into adulthood.

As children become teenagers some sports such as basketball become more contact – therefore although these sports may have been possible when they child was younger it may have more risks in adolescents.

Use this link to complete these questions - Playing it Safe

|

Click on the following link to view the 'UK Physical Activity Guidelines' from the Department of Health:

|

Personal Protective Equipment[edit | edit source]

Protective equipment can be worn by individuals to minimise risk of bleeding either at a very young age or when taking part in sports and activities at an older age[71]. This is generally used considering personal preference, the child’s compliance and level of sporting activity undertaken. Splints or braces can be useful in protecting target joints whilst participating in sports[72].

Joints which are considered at high risk of bleeds are the elbows, wrists, knees and ankles. Toddlers are encouraged to be protected with elbow and knee pads when crawling and helmets can also be beneficial to protect children from falls, especially when cycling or running. Due to the introduction and advances in prophylaxis, the need for protective equipment in day to day activities has been reduced. It has also been suggested that although previously considered extremely important and beneficial, the social risks now outweigh the potential benefits of protective equipment. However, this is a decision that must be made based on the type and competitiveness of the activity the individual is participating in.

There are many different types of protective equipment available and multiple ways of modifying home environments to make it safer for toddlers and young children.

An example of the various different types of protective equipment are shown in the table below:

Table 5. Examples of protective headgear[73]

| • Physical activity promotion exists worldwide. • Considerations include target joints, appropriate sporting activities, timing of prophylaxis • Protective equipment can be used to protect all limbs and head when partaking in sports • AWH should be reviewed every 6 months by a physiotherapist • Weight bearing activities should be encouraged to encourage bone mineral accrual • Contact sports are not recommended |

How to Approach Conversations Regarding Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

It can sometimes be difficult for a physiotherapist to approach a conversation regarding how much physical activity an individual undertakes. It can often be challenging to encourage change in a person’s behaviour and can be increasingly difficult in AWH due to the nature of the condition. This issue is particularly relevant for AWH as this is normally a stage in their life where physical activity levels reduce (REF). Physiotherapists can offer education and advice about what type of activity to undertake in order to prevent bleeds occurring. More recommendations about this have been discussed previously in the education and recommendations sections.

Appropriate communication is essential when discussing physical activity with patients. The Royal College of General Practitioners[74] makes recommendations on how to communicate ideas to a patient.

Here are some tips and approaches which can facilitate behavioural change in an AWH:

• Be aware of the amount of information you provide – careful not to overload them.

• Avoid the use of technical vocabulary as it may cause confusion.

• Use different methods other than verbal communication to provide information e.g. leaflets, video, online resources.

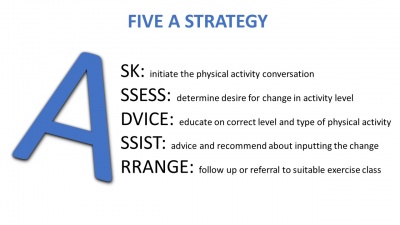

Figure 12. 5 A strategy of discussion

Brief interventions involve short advice and support sessions providing information for the patient regarding the process of behavioural change. One method of brief intervention is the 5 A Strategy[75]. The picture on the right shows what this involves:

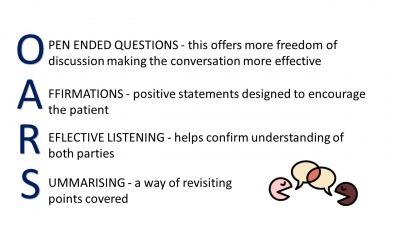

Finally OARS is a form of motivating the patient through communication. The diagram below explains how to use OARS[76]:

Figure 13. OARS strategy of communication

Complete the reflective task below. Consider if this conversation could have been improved using the techniques above.

To help you construct your reflection you may wish to use reflective models such as Gibbs or Rolfe.

Benefits of Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

In this section of the wiki, benefits of physical activity in AWH will be discussed. This will include physical inactivity and obesity, childhood development, psychosocial factors associated with physical activity and supporting evidence.

The learning outcomes to be addressed in this section are:

3. Using the biopsychosocial model, evaluate the physical, spiritual and emotional needs which must be considered when treating an adolescent with haemophilia.

4. Critically appraise the evidence base surrounding physical activity in an adolescent with haemophilia.

NHS Lothian - Haemophilia: Get Fit & Active

[edit | edit source]

This video offers some general advice and recommendations regarding increasing physical activity in PWH. It follows the story of Sean, an individual with haemophilia, as he discusses some of the benefits he believes are associated with being physically active when living with this condition.

Video available for use with permission from Clinical Specialist Physiotherapist Jenna Reid.

Physical Activity Relating to Obesity[edit | edit source]

Recent progress in the management of haemophilia over the past few decades has seen improvements in average lifespan of AWH, now matching that of a healthy individual[77]. These changes however, have introduced other new issues to tackle in the coming years.

Childhood obesity is prevalent in AWH, as well as the general population. However, the consequences of weight gain in sufferers can cause additional issues, such as increased risk of joint arthropathy[78]. Excess weight can induce joint bleeds due to added stresses placed on the joints [79]. Effects of obesity and overweight can also exacerbate existing arthropathies and influence development of cardiovascular disease[80].

Parental influence is also considered to be a contributing factor to obesity and overweight in this population. Many parents tend to be very protective over their child, preventing them from engaging in physical activity. It was not until the 1970s that exercise in this population was recognised as effective. Prior to this it was considered to increase the risk of haemarthroses[81]. A previously discussed, it is now recommended for particular activities, mainly swimming, with aims of improved quality of life. This new treatment approach is largely due to recent advances in safety and availability in the clotting factor used to prevent bleeds[82]. Buzzard and Beeton[83] also report evidence to suggest changes in blood clotting factors due to exercise.

The benefits of physical activity in the general population are widely known, providing general health improvements along with potential enhancement in disease outcomes[84]. However, Philpott et al.[85] believe children suffering with a chronic disease or disability are less active than their age-matched healthy peers. A study conducted by Hofstede et al.[86] comparing healthy subjects to AWH reiterates; revealing triple the number of obese boys with haemophilia in relation to the comparable healthy subjects. Contrary to this finding, a 2010 study quantifying physical activity levels through accelerometry, revealed AWH to be more involved in physical activity compared to their healthy peers. However, the study also stated the time dedicated to physical activity was mainly focused towards low-intensity activities and sedentary behaviours[87]. Several studies have reported an association between an increase in obesity levels and sedentary behaviours particularly amoung AWH. This increase is concerning, however does not differ much from the un-affected population[88];[89].

There is lacking evidence available to claim that there is a true correlation between reduced exercise levels in AWH and increased weight or obesity and further study must be carried to clarify these findings. However, this information confirms the need for lifestyle modifications in this population, including dietary changes and promotion of physical activity. The overall consensus, as previous stated, is that an accumulation of 60 minutes or more physical activity of moderate intensity, consisting of both aerobic daily activity and vigorous intensity aerobic activity across a minimum of 3 days per week is advised [90]. However, the physical activity recommendations remain limited[91];[92], with findings from recent studies demonstrating controversial outcomes.

Evidence Table[edit | edit source]

The table below describes some articles surrounding the evidence base for obesity in PWH.

Table 6. Evidence surrounding obesity in AWH and limitations of each

| Author/ Title | Purpose/Aims | Details/Protocol | Measures | Conclusions | Limitations |

| Hofstede et al.[93] Obesity: a new disaster for haemophiliac patients? A national survey |

To determine the prevalence of overweight and obesity in haemophilia patients in the Netherlands, assessed over a decade. | A nationwide postal survey among all haemophilia patients in the Netherlands was conducted in 2001, following four previous surveys in 1972, 1978, 1985 and 1992. Data on length, weight, age and severity of haemophilia were obtained. The haemophilic boys where restricted to those aged 4–16 years. | None. | Prevalence of obesity tripled between 1992 and 2001. The aetiology is similar to that in the general population as can be attributed to a more sedentary lifestyle and bad diet habits. Boys with haemophilia are especially at risk of becoming overweight as parents may be protective over their child and limit physical activities in order to prevent bleedings. Physical activity should be promoted in all these patients. | Study was conducted in the Netherlands reduces transferability. |

| Majumdar et al.[94] Alarmingly high prevalence of obesity in haemophilia in the state of Mississippi |

To estimate the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults diagnosed with haemophilia in Mississippi and to assess whether race/ethnicity and the severity of haemophilia are important risk factors. | A retrospective chart review was performed for all haemophilic patients seen within the last 2 years at the Mississippi Haemophilia Treatment Centre. 132 haemophilic patients. Overall, 51% of the haemophilic patients were either obese or overweight. Height and weight records were obtained and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated. | None. | There is a significantly higher prevalence of being overweight or obese age >20 years. However, examination of subgroups within the 2–19.9 age range demonstrated a higher prevalence of obesity in haemophiliacs aged 11–19.9 years compared with younger patients. This suggests a trend for haemophilic patients gain excess weight during the adolescent period. Race/ethnicity and severity of haemophilia were not significant risk factors for overweight and obesity. | Cross-sectional observational study, therefore only offers a snapshot of results. The study was conducted in Mississippi in America therefore reducing transferability UK populations. |

| Gonzales et al.[95] Comparison of physical activity and sedentary behaviours between young haemophilia A patients and healthy adolescents. |

To determine the amount and intensity of habitual PA among haemophilia A and healthy adolescents, and in haemophilia A patients with and without bleeding episodes in the previous year. To identify the type and determine the time spent in sedentary activities in which both groups participate to obtain a broadened view of their daily activities. |

A cross-sectional study of 41 adolescent patients with haemophilia A and 25 healthy adolescents, aged 8–18 years. Participants with haemophilia A met the following clinical criteria: attended the hospital during the previous year, had all of the habitual clinical assessments made and had not experienced any bleeding during the 2 months prior to the assessments. Healthy participants were selected from secondary schools in the same region. The PA of participants was measured using an accelerometer. | Adolescent Sedentary Activity Questionnaire | Adolescent haemophilia A patients showed a higher daily mean time engaged in PA compared to healthy participants. Findings suggest that increased participation in moderate intensity PA and reduced sedentary behaviours should be recommended among adolescents with haemophilia A. The current findings show that the PA in which haemophilic youth were engaged were insufficient to gain physiological benefits. An increase in the time spent on moderate physical activities should be fostered. Furthermore, patients should be cautioned to reduce the amount of time sedentary. | One of the main limitations of the study is that the accelerometer cannot be worn in water. Also, the characteristics of the healthy counterpart group could have been more carefully selected, as they belonged to the same school. This may be the reason why possible differences between the two groups regarding the use of transportation could not be addressed. |

| Douma-van Riet et al.[96] Physical fitness in children with haemophilia and the effect of overweight. |

To assess physical fitness (aerobic capacity), muscle strength, join t status. To determine the prevalence of overweight. To study whether overweight is associated with physical fitness, motor competence and quality of life (QoL). |

Patients treated at five Centres in the Netherlands were invited to participate a study. All boys aged 8–18 diagnosed with haemophilia A were invited to participate. BMI was calculated. The children performed a maximal aerobic exercise test and were encouraged to cycle to exhaustion. Other areas used 6-min walk test (6MWT). Quality of life was measured with the Haemo-QoL Index, which represents the core content of the Haemo-QoL. Muscle strength, motor competence and joint mobility were assessed. | 6MWT | The results from this multi-centre study show that Dutch children with haemophilia are physically as fit as their healthy peers; overall aerobic capacity and muscle strength are comparable to healthy children. The prevalence of overweight is only slightly increased compared with the general population. | Although the 6MWT is a standardised test, in the three centres the walking courses used were not identical. Also in one of the centres, where the highest z-scores of walking distance were found, children inadvertently received extra encouragement. Therefore, some of the results on the 6MWT should be interpreted with caution. |

Complete the task below.

You can use the CASP or the PEDro checklist to help you with the appraisal.

Childhood Development[edit | edit source]

Adolescents undergo more physical changes at this age than throughout any other stage of life after birth. Rate of growth in itself can predispose the child to bleeds. Growth spurts around puberty may decrease the muscle mass surrounding joints and consequently increase joint bleeding during this period[97].

Weight-bearing activity is crucial in ensuring adequate generation of bone mass throughout childhood and may be even be considered more important than calcium intake through diet[98]. A study conducted in 2008, by Tlacuilo-Parra et al.[99] revealed a significant reduction in lumbar spine bone mineral density in children with haemophilia in comparison to healthy subjects of matched age and sex. The results demonstrated statistically significant differences in activity between the groups, with the haemophilia population at three times the risk of inactivity. These results confirm that long periods of inactivity and immobility, with reduced weight-bearing (such as following joint bleeds) are directly related to low bone mineral density in AWH.

Psychosocial factors associated with physical activity

[edit | edit source]

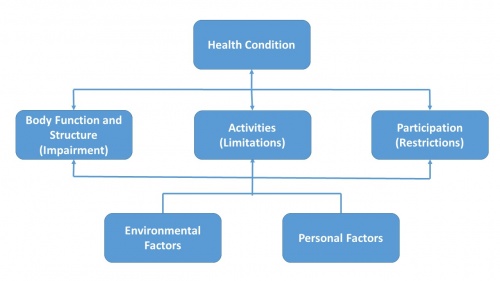

Due to the nature of the condition, AWH are usually diagnosed and aware of their condition from a very young age. The childs parent or guardian will also be affected due to their involvement in the care and management of the individual in the early years[100]. There are psychosocial, as well as physical barriers which can be managed using the ICF model[101].

Figure 14. ICF model

Recent evidence discussed throughout this wiki resource supports exercise, allowing AWH to participate in peer activities which they would have previously been excluded from[102].

The World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) separates a number of different psychosocial issues into specific age groups[103]:

• Infant to toddler (newborn to age 5)

• Early childhood (6-9 years)

• Pre-adolescence (10-13 years)

• Adolescence (14-17 years)

• Adulthood (18 years +)

It is important that at every stage of the child’s journey there is help and support available to the individual and family to ensure that psychosocial barriers are minimised[104]. Some of the psychosocial issues that are common in adolescence are discussed below.

Transition phase

In the adolescence stage, where there is a transition of care from paediatrics to general practitioners. At this stage it is important to focus on self -management and independence in treatment. From pre-adolescence to late teenage years, individuals will become more independent and involved in managing their condition and self- treating. Although this leads to increased confidence in their own bodies as they are able to confidently treat themselves, a common barrier with this at this age is compliance.

Compliance

Cassis[105] states that at this stage developmentally, teens are focussed on present events and do not consider the future consequences that poor management of their condition could cause. Also as a child starts to mature, other activities may take more of a priority over physiotherapy or exercises and it is important that they are made aware of the harmful consequences that this could lead to.

Physical activity can play a large part in a child’s social and emotional well-being. Through team-based sports they learn how to work with other peers. Improved emotional status has also demonstrated marked clinical benefits with reported reductions in spontaneous bleeds[106].

Cassis et al.[107] conducted a systematic review which looked at 24 studies relating to the psychosocial aspects of haemophilia. It found that psychosocial factors have a significant impact on quality of life for patients with chronic conditions such as Haemophilia. One of the studies, found that in haemophilia one of the most common stressors associated with psychological factors is limitations to an active lifestyle including sports and other physical activities. This may be due to the fear of causing a bleed or stigma associated with the protective equipment that is sometimes required to safely participate in sports.

The literature review also found that for PWH, participation in physical activites and sports is associated with positive effects not only for physical well-being but also on self-esteem and social interactions. This is supported further in a study by Sherlock[108] which found that the non-physical benefits of sporting activities included improved self-esteem and perceived social acceptance. It also supported the above view that quality of life in PWH is impaired by limitations in sporting activity.

However, Buxaum et al.[109] conducted a study which aimed to ascertain social and cognitive factors associated with exercise in PWH aged between 11 and 18. The Peirs Harris Childrens Concept Scale and the Childrens Manifest Anxiety Scale are self-reported scales that were used to measure self-esteem and anxiety in PWH. This study found no differences in the scores obtained in these outcomes between PWH and healthy controls. Although this conflicts with previous evidence only 17 participants in the Haemophilia group were recruited and therefore results must be taken with caution due to small sample size.

Although results are supported well by similar studies, it is evident that research into the psychosocial aspects of haemophilia is limited[110] and actual participation in physical activity among PWH has not been well studied[111].

| • Childhood obesity is prevalent in AWH • Excess weight can induce joint bleeds due to added stresses placed on the joints • Obesity can exacerbate existing arthropathies and influence development of cardiovascular disease • Over protective parents can prevent children from participating in physical activity • Adolescents undergo more physical changes at this age than throughout other stage of life after birth • Growth spurts around puberty may decrease the muscle mass surrounding joints leading to increased joint bleeds • Psychosocial factors affect every age group from new born to 18+ • The ICF model can be used to help manage psychosocial factors • Participation in physical activity brings positive effects for physical well-being, self-esteem and social interactions |

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

You have now reached the end of this online module. Well done!

By now you should have hopefully achieved the learning outcomes that your were introduced to at the beginning of the wiki.

Table 7. Learning Outcomes

With recent improvements in medical management, AWH are now living on average as long as healthy individuals[112]. Therefore, it is important that we, as physiotherapists, encourage a healthy lifestyle.

There is a big national drive towards physical activity promotion in the general population[113]. This is even more important in the population of AWH due to the previously discussed benefits.

As one of the main health professionals involved in the care of this population, we have the potential to have a large influence on their lifestyle choices. Therefore it is fundamental that we have the adequate knowledge to appropriately understand and manage the condition.

Answers[edit | edit source]

Answers to quiz in section 2.5 Quiz:

1. A 2. Factor 9 3. 25% 4. 1:4

Answers to the case study in section 3.1 Assessment:

| Subjective | Consider age, gender, severity and type of haemophilia, medical management, recent history any recent bleeds/target joints and social circumstances |

| Objective | An overall comprehensive biomechanical and functional assessment with specific focus towards presenting condition and symptoms. Consider use of standardized outcome measures to provide a baseline of symptom severity and activity limitations. |

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World Health Organization. Physical Activity. http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/ (accessed 25 January 2016).

- ↑ Casperson SJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health Rep 1985; 100:2:126–131. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1424733/ (accessed 25 January 2016).

- ↑ Bloom, B.S, Engelhart, M. D, Furst, E. J, Hill, W.H, Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. New York: David McKay Company, 1956.

- ↑ Buzzard B, Beeton K. Physiotherapy Management of Haemophilia. Oxford: Wiley, 2008.

- ↑ World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 October 2015).

- ↑ Buzzard B, Beeton K. Physiotherapy Management of Haemophilia. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- ↑ The Knowledge and Skills Framework. Understanding KSF Dimensions. http://www.ksf.scot.nhs.uk (accessed 10th Jan 2016)

- ↑ VARK-Learn. The VARK Questionnaire. How Do I Learn Best? http://vark-learn.com/the-vark-questionnaire/ (viewed 28th November 2015)

- ↑ NHS Choices. Haemophilia. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/haemophilia/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ World Federation of Haemophilia. Severity of hemophilia. http://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=643 (accessed 7 January 2016).

- ↑ Great Ormond Street Hospital. What causes Haemophilia? http://www.gosh.nhs.uk/medical-information/search-medical-conditions/haemophilia (accessed 10 Jan 2016).

- ↑ The Haemophilia Society. Haemophilia A.fckLRhttp://www.haemophilia.org.uk/bleeding_disorders/bleeding_disorders/haemophilia_a (accessed 9 November 2015).

- ↑ The Haemophilia Society. Haemophilia B. fckLRhttp://www.haemophilia.org.uk/bleeding_disorders/bleeding_disorders/haemophilia_fckLRb (accessed 9 November 2015).

- ↑ Haemophilia Information. Haemophilia Genetics. http://www.hemophilia-information.com/hemophilia-genetics.html (accessed 12 September 2015).

- ↑ Grethlein SJ. Acquired Haemophilia. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/211186-overview#a2fckLR(accessed 7 January 2016).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Haemophilia Federation of America. Inheritance Pattern of Hemophilia. http://www.hemophiliafed.org/bleeding-disorders/hemophilia/inheritance/ (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ 19. Preston FE, Kitchen S, Jennings L, Woods TA, Mackris M. SSC/ISTH classification of hemophilia A: can hemophilia center laboratories achieve the new criteria? J Thromb Haemost 2004:2:271-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14995989 (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Haemophilia symptoms. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Haemophilia/Pages/Symptoms.aspx (accessed 10 Jan 2016).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Haemophilia Information. Three levels of Haemophilia severity. http://www.hemophilia-information.com/types-of-hemophilia.html (accessed 12 Sept 2015).

- ↑ National Haemophilia Foundation. Severity. https://www.hemophilia.org/Bleeding-Disorders/Types-of-Bleeding-Disorders/Hemophilia-A 2 (accessed 8 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Pavlova A, Oldenburg J. Defining severity of haemophilia: more than factor levels. Semin Thromb Hemost 2013;39(7):702-10.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24026911 (accessed 12 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Haemophilia Care. When to have treatment. http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/when-to-have-treatment.html (viewed 12th Sept 2015)

- ↑ Berntorp E, Shapario AD. Modern haemophilia care. Lancet 2012; 14;379:9824:1447-56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22456059 (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Nilsson IM, Hedner U, Ahelberg A. Haemophilia prophylaxis in Sweden. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 1976;65:129– 135.

- ↑ Khoriaty R, Taher A, Inati A, Lee C. A comparison between prophylaxis and on demand treatment for severe haemophilia. Clinical Laboratory Hematology 2005;27(5):320-3.

- ↑ Johannes Oldenburg. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia: achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens. American Society of Hematology 2015. http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/early/2015/02/23/blood-2015-01-528414.article-infofckLR(viewed 20th Sept 2015)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Breakey VR, Blanchette VS, Bolton-Maggs PHB. Towards comprehensive care in transition for young people with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2010;16(6);848-857. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02249.x/abstract (accessed 18 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Department of Health. Multidisciplinary teams (MDT’s). http://www.health.nt.gov.au/Cancer_Services/CanNET_NT/Multidisciplinary_Teams/index.aspx (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Physiotherapy works for social care – Why Physiotherapy? http://www.csp.org.uk/physiotherapy-works-social-care (accessed 10 Jan 2016).

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association. Outcome Measures in Patient Care. http://www.apta.org/OutcomeMeasures/ (accessed 20 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Haemophilia Care. How to recognise a bleed. http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/how-to-recognise-a-bleed.html (accessed 7 Jan 2016)

- ↑ International Prophylaxis Study Group. HJHS. http://ipsg.ca/working-groups/physical-therapy/info/hjhs (accessed 15 Dec 2015).

- ↑ World Federation of Haemophilia, Paediatric Haemophilia Activities List: http://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=886 (accessed 20 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Stephensen D, Drechsler WI, Scott OM. Outcome measures monitoring physical function in children with haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia 2014;20:306-321. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hae.12299/epdf (accessed 19 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Buzzard B, Beeton K. Physiotherapy Management of Haemophilia. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- ↑ Haemophilia Care. How is Physiotherapy used in Haemophilia care. http://www.haemophiliacare.co.uk/physiotherapy.html (accessed 10 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Talking Joints. Let’s talk about physiotherapy for haemophilia patients. https://www.novonordisk.com/content/dam/Denmark/HQ/aboutus/documents/cpih-2015-talkingjoints-brochure-lets-talk-physiotherapy.pdf (accessed 10 Oct 2016).

- ↑ Hermans C, De Moerloose P, Fischer K, Holstein K, Klamroth R, Lambert T, Lavigne-Lissalde G, Perez R, Richards M, Dolan G. European Haemophilia Therapy Standardisation Board. Management of acute haemarthrosis in haemophilia A without inhibitors: literature review, European survey and recommendations. Haemophilia 2011;17(3):383-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21323794 (accessed 30 Sept 2015).

- ↑ Gomis M, Querol F, Gallach JE, Gonzalez LM, Aznar JA. Exercise and sport in the treatment of haemophilic patients: a systematic review. Haemophilia 2009;15:1:43-54. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18721151 (accessed 10 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Mulder K. Exercises for people with haemophilia. Montreal: World Federation of Haemophilia. 2006. http://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar_url?url=http%3A%2F%2Fhaemophilia.ie%2FPDF%2FExercise_Guide_med.pdf&hl=en&sa=T&oi=ggp&ct=res&cd=0&ei=PzyiVtjZA8SmmAHg2rKgBw&scisig=AAGBfm1u24jVgQuILSUxSIt96TVBQMLeLg&nossl=1&ws=1366x599 (accessed 22 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Heijnen L, Buzzard BB. The role of physical therapy and rehabilitation in the management of hemophilia in developing countries. Semin Thromb Hemost 2005;31(5):513-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16276459 (accessed 25 Sept 2015).

- ↑ 45.Blamey G, Forsyth A, Zourikian N, Short L, Jankovic N, Kleijn PDE, Flannery T. Comprehensive elements of a physiotherapy exercise program in haemophilia – a global perspective. World Federation of Haemophilia 2010;16:136-145 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02312.x/abstract;jsessionid=BB3B137A0C21342D378A949A977850CA.f04t01fckLR(accessed 10 Oct 2015).

- ↑ World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Heijnen L. Rehabilitation and the role of the physical therapist. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1993;24(Suppl. 1):26–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3570911/ (accessed 25 Sept 2015).

- ↑ Buzzard B. Physiotherapy for Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Haemophilic Synovitis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. Orthopaedics and Related Research 1997;343:42-46. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9345204 (accessed 9 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Tiktinsky R, Falk B, Heim M, Martinovitz U. The effect of resistance training on the frequency of bleeding in haemophilia patients: a pilot study. Haemophilia 2002;8:22–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11886461 (accessed 15 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Negrier C, Seuser A, Forsyth A, Lobet S, Llinas A, Roas M, Heijnen L. The benefits of exercise for patients with haemophilia and recommendations for safe and effective physical activity. Haemophilia 2013;19:4:487-498. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23534844 (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report. http://health.gov/paguidelines/report/pdf/committeereport.pdf (accessed 17 Jan 2016).

- ↑ World Federation of Hemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2012;2:6-73. 2012. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).

- ↑ McGee S et al. Organized sports participation and the association with injury in paediatric patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2015;21(4):538-542. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2786948/ (accessed 15 Nov 2015).

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 World Federation of Heamophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015). Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "WFH GUIDELINES" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Philpott J, Houghton K, Luke A. Physical activity recommendations for children with specific chronic health conditions: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hemophilia, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Paediatrics &amp; Child Health 2010;15(4):213-218. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2866314/ fckLR(accessed 6 Oct 2015).

- ↑ The Kings Fund. Inequalities in life expectancy Changes over time and implications for policy. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/inequalities-in-life-expectancy-kings-fund-aug15.pdf (accessed 24 Nov 2015).

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Physio 15: Physios can improve public health by influencing behaviour and promoting physical activity. http://www.csp.org.uk/news/2015/10/21/physio-15-physios-can-improve-public-health-influencing-behaviour-promoting-physical (accessed 27 Nov 2015).

- ↑ World Health Organization. Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (accessed 28 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Corporate Policy and Strategy Committee. Physical Activity for Health Pledge. 2-12 www.edinburgh.gov.uk . (accessed 8 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Nazzaro AM, Owens S, Hoots WK, Larson KL. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of youths in the US hemophilia population: results of a national survey. American Journal of Public Health 2006;96(9):1618-1622. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16873741 (accessed 3 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Negrier C, Seuser A., Forsyth A., Lobet S, Llinas A, Roas M, Heijnen L. The benefits of exercise for patients with haemophilia and recommendations for safe and effective physical activity. Haemophilia 2013;19(4):487-498. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23534844 (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, Andersen LB, Owen N, Goenka S, Montes F, Brownson RC. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012; 380(9838):272-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22818939 (accessed 26 Jan 2016).

- ↑ World Health Organization. Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (accessed 28 Dec 2015).

- ↑ Department of Health. Multidisciplinary teams (MDT’s). http://www.health.nt.gov.au/Cancer_Services/CanNET_NT/Multidisciplinary_Teams/index.aspx (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Manco-Johnson MJ, Riske B, Kasper CK. Advances in care of children with haemophilia. Seminars in Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2003;29(6):595-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14719175 (accessed 6 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Riske B. Sports and exercise in haemophilia:benefits and challenges. Haemophilia 2007;103:29-30. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01503.x/epdf. (accessed 15 Jan 2016).

- ↑ World Federation of Haemophilia. Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia. Canada: Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2012;2:6-73. http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Anderson A, Forsyth A. Playing it safe: Bleeding Disorders, Sport and Exercise New York: National Haemophilia Foundation. 1- 44. https://www.hemophilia.org/…/docume…/files/PlayingItSafe.pdf (accessed 6 Oct 2015).

- ↑ World Federation of Haemophilia. About bleeding disorders. http://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=642 (accessed 7 Jan 2016).

- ↑ The Haemophilia Society. Inhibitors. http://www.haemophilia.org.uk/bleeding_disorders/bleeding_disorders/inhibitors (accessed 26 Jan 2016).