Plantar Fasciitis

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Admin, Kris Porter, Rachael Lowe, Elien Lebuf, Bert Pluym, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Jonathan Wong, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Brooke Kennedy, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Jeroen Van Cutsem, Thomas Janicky, Elke Lathouwers, Vidya Acharya, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Lisa Couck, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tony Lowe, Khloud Shreif, Keta Parikh, Stijn Van de Vondel, WikiSysop, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Rishika Babburu, Padraig O Beaglaoich, Jessica Galasso, Sehriban Ozmen, Shaimaa Eldib, Yahya Al-Razi, Claire Knott, Saud Alghamdi, David Csepe, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell and Jarapla Srinivas Nayak

Original Editor - Brooke Kennedy

Top Contributors - Admin, Kris Porter, Rachael Lowe, Elien Lebuf, Bert Pluym, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Jonathan Wong, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Brooke Kennedy, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Jeroen Van Cutsem, Thomas Janicky, Elke Lathouwers, Vidya Acharya, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Lisa Couck, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tony Lowe, Khloud Shreif, Keta Parikh, Stijn Van de Vondel, WikiSysop, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Rishika Babburu, Padraig O Beaglaoich, Jessica Galasso, Sehriban Ozmen, Shaimaa Eldib, Yahya Al-Razi, Claire Knott, Saud Alghamdi, David Csepe, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell and Jarapla Srinivas Nayak

Topic Expert - Kris Porter

Search Strategy

[edit | edit source]

We searched scientific articles and more information by using the websites PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar and PEDro. We used the keywords: “plantar fasciitis”, “rehabilitation”, “physiotherapy”, “plantar fasciosis” and “plantar heel pain”.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis may be referred to as plantar fasciosis, plantar heel pain, plantar fascial fibramatosis, among others. The pathology that is usually present in the medial heel region has traditionally been known as plantar fasciitis. However, recently, the term plantar fasciosis has been used to dismiss the inflammatory component and emphasize the degenerative nature that is observed histologically in the insertion zone in the calcaneus [34]. The fact that many cases diagnosed as “plantar fasciitis” are not inflammatory conditions, and thus should be referred to as "plantar fasciosis”, is confirmed through histological analysis which demonstrates plantar fascia fibrosis, collagen cell death, vascular hyperplasia, random and disorganized collagen, and avascular zones [2]. There are many different sources of pain in the plantar heel besides the plantar fascia, and therefore the term "Plantar Heel Pain" serves best to include a broader perspective when discussing this and related pathology.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

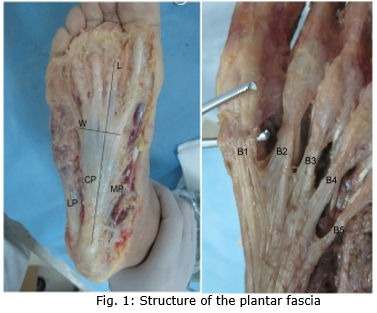

The plantar fascia is comprised of white longitudinally organized

fibrous connective tissue which originates on the periosteum of the medial calcaneal tubercle, where it is thinner but it extends into a thicker central portion. The thicker central portion of the plantar fascia then extends into five bands surrounding the flexor tendons as it passes all 5 metatarsal heads. The plantar fascia blends with the paratenon of the Achilles tendon, the intrinsic foot musculature and even the skin and subcutaneous tissue.[2][3] The thick viscoelastic multilocular fat pad is responsible for absorbing up to 110% of body weight during walking and 250% during running and deforms most during barefoot walking vs. shod walking.[4]

Pain in the plantar fascia can be insertional and/or non-insertional and may involve the larger central band, but may also include the medial and lateral band of the plantar fascia. The plantar fascia is best referred to as fascia because of it's relatively variable fiber

orientation as opposed to the more linear fiber orientation of aponeurosis.[49]

Epidemiology & Etiology

[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of pain in the hind foot and region of the heel is high in both athletic and non athletic regions. Although it occurs more frequently in running-related activities such as running,soccer and gymnastics. [39]

Although this condition is seen in all ages, it is most commonly experienced during the age between 20 and 34 years old.[40]

Plantar fasciitis accounted for 8% of the reported previous overuse, with a greater incidence in female runners. [11,59]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are many risk factors which contribute to plantar heel pain :

Presence of limited ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, high body mass index in nonathletic individuals, running and work-related weight-bearing activities, particularly under conditions with poor shock absorption [46]

Risk factors in runners are, street running, spiked shoes and hind-foot varus [42] , an increased height (57). Greater rates of increase in vertical ground reaction forces and a lower medial longitudinal arch where found in female runners (56).

In an nonathletic population a strong association is found between a higher body mass index and plantar heel pain (43), also work-related weight-bearing activities such as prolonged standing on hard surfaces, walking and number of times jumping in and out of vehicles (60).

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Heel pain/plantar fasciitis usually presents as a chronic condition, with symptom duration greater than one year prior to seeking treatment. The mean duration of symptoms last longer than 6 months (8,10,50,52,61).

Plantar medial heel pain, most noticeable with initial steps after a period of inactivity (46)

A typical presentation of the pain is early in the morning. Once starting walking, the pain tends to recede, but never fully resolves throughout the course of the day (50).

Pain is worse following prolonged weight bearing, such as prolonged walking or exercise, particularly on hard surfaces (46).

Nonathletic individuals present often with a high body mass index. (43)

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis is complex, as there may be pain from more than one structure.

Possible other sources of medial heel pain are fat pad atrophy (61), calcaneal apophysis in adolescents (58), tibialis posterior dysfunction (54), proximal plantar fibroma (51), neural sources like S1 radiculopathy and tarsal tunnel syndrome (58), stress fractures (calcaneum, talus and navicular bone), plantar fascia rupture and rheumatological diseases (53)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis. It is based on patient history and physical exam. Therefore, there are a couple of risk factors which the examiner has to bear in mind while examining the patient fort he first time. These are the presence of limited ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, high body mass index in nonathletic individuals, running, and work-related weight-bearing activities. [46] (level 1A)

Also one of the most important clinical findings us pain in the plantar medial heel region (most noticable in the morning, the first staps after a period of inactivity or after prolonged weight bearing activities) [46, 47, 48]

There is a possibility of using imaging diagnostics, but it is not recommended for the initial evaluation. However, imaging such as MRI can be required to rule out other considerations in the differential diagnosis. [48] (level 1A)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- The FAAM, or Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, is a good outcome measure to give to patients that are diagnosed with plantar fascitis.

- The Foot Function Index, or FFI but only the the pain subscale. It is a validated measure, and the first 7 items of the pain subscale are used as the primary numeric outcome measure. Items are scored from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) depending on the mark on the visual analog scale. The sum of the 7 items is then expressed as a percentage of maximum possible score, ranging in an overall percentage.

- The foot health status questionnaire

- The Bristol foot score can be used for assess the patient’s perception of the impact of foot problems on everyday life. It’s also a relevant questionnaire to determine satisfaction of foot orthotics.. There are 15 questions: foot concern and pain (7), footwear and general foot health (4) and mobility (3).

- The foot health status questionnaire, or FHSQ can be used to assess the effects of footwear and orthotic interventions (30).

Examination[edit | edit source]

The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use imaging studies like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI.

Fabrikant et al could conclude that office-based ultrasound can help diagnose and confirm plantar fasciitis/fasciosis through the measurement of the plantar fascia thickness. Because of the advantages of ultrasound-that it is non-invasive with greater patient acceptance, cost effective and radiation-free-the imaging tool should be considered and implemented early in the diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis/fasciosis. [13] (level 3)

Sutera et al found that imaging the ankle/hind foot in the upright weight-bearing position with a dedicated MR scanner and a dedicated coil might enable the identification of partial tears of the plantar fascia, which could be overlooked in the supine position. [14] (level 3)

Risk factors to look for by the examination of plantar fasciitis are:

- Limited active and passive talocrural joint dorsiflexion range of motion

- Obesity or high body mass index in nonathletic individuals

- Work-related weight-bearing

These findings also indicate the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis [46] (level 1A):

- Plantar medial heel pain: most noticeable with initial steps after a period of inactivity but also worse following prolonged weight bearing

- Active and passive talocrural joint dorsiflexion range of motion

- Pain with palpation of the proximal insertion of the plantar fascia

- Positive windlass test

- Negative tarsal tunnel tests (Tinel's test, for further information see tarsal tunnel syndrome)

- Abnormal FPI score

- The longitudinal arch angle

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis frequently responds to a broad range of conservative therapies. Modalities commonly used include rest, ice massage, stretching of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), corticosteroid injections, foot padding, taping, shoe modifications (steel shank and anterior rocker bottom), arch supports, heel cups, custom foot orthoses, night splints, ultrasound, and casting [36, 38].

The use of oral NSAID’s in treatment for plantar fasciitis has proven to be significantly helpful in improving pain and disability. Pain and disability mean scores improve significantly over time with use of NSAID’s. There was a trend towards improved pain relief and disability, especially in the interval between the 2 and 6- month follow-up. Pain improved from baseline to 6 months by a factor of 5.2 and disability by 3.8. These results are quantified by using the Foot Function Index [36].

Other forms of conservative therapy used for treating acute plantar fasciitis include use of corticosteroid injections and ultrasound therapy. When used, pain intensity may reduce significantly.

However, the pain reduction achieved by corticosteroid injection has been proven to be significantly greater when compared to pain relief after undergoing ultrasound therapy (p<.0001). Although corticosteroid injections have proven to be effective in treating heel pain, and has better therapeutic outcomes than ultrasound therapy, treatment failure occurs quite frequently (>30% of cases). When assessing pain reduction and functional outcomes, the improvements achieved by corticosteroid injections only seem to continue untill 12 weeks and thus does only cover acute symptoms [45, 46].

When conservative measures fail, surgical plantar fasciotomy with or without heel spur removal may be employed. There is a method, through an open procedure, percutaneously or most common endoscopically, that releases the plantar fascia. This is an effective treatment, without the need for removal of a calcaneal spur, when present. There is a professional consensus, 70-90% of heel pain patients can be managed by non-operative measures. Surgery for plantar fasciitis should be considered only after all other forms of treatment have failed. With an endoscopic plantar fasciotomy, using the visual analog scale, the average post-operative pain was improved from 9.1 to 1.6. For the second group (ESWT), using the visual analog scale the average post-operative pain was improved from 9 to 2.1. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy gives better results than extra-corporeal shock wave therapy, but with liability of minor complications.[15][16]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

The most common treatments include stretching of the gastroc/soleus/plantar fascia, orthotics, ultrasound, iontophoresis, night splints, joint mobilization/manipulation, and surgery.

1. Stretching[edit | edit source]

Stretching Plantar fascia:

- The patient cross their affected leg over the contralateral leg and using the fingers across to the base of the toes to apply pressure into toe extension until a stretch can be felt along the plantar fascia. (figure 2)

- Step test: the patient position himself on a step with the ball of his foot and drops his heel while remaining the forefoot on the step. (figure 3)

- The patient can also use a towel to stretch the plantar fascia while sitting. The towel goes around the forefoot and the patient pulls the forefoot in dorsiflexion27 (level 1A). (figure 5)

- Rolling the foot (plantar fascia) over a tennis ball.28 (level 1B) (figure 4)

Stretching of the achilles tendon, soleus and gastrocnemius:

- The achilles tendon can be stretched in a standing position with the affected leg placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee was then bent, keeping the back knee straight and heel on the ground. In this position is the gastrocnemius stretched as well. (figure 6)

- If the patient wants to focus more on the soleus muscle, the back knee could then be in a flexed position[17](level 2B) . (figure 7)

Key Research[edit | edit source]

DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia stretching exercises enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2003;85-A:1270-1277.

According to a prospective, randomized controlled trial by DiGiovanni, stretching can be an appropriate treatment for plantar fascitis as long as it is specific stretching. He compared patients who received either a plantar-fascia tissue-stretching program compared to patients who received an achilles tendon stretching program. The plantar fascia stretching consisted of one stretch to be performed before taking their first step in the morning. The patient crossed the affected leg over the contralateral leg and used the fingers across to the base of the toes to apply pressure into toe extension until a stretch was felt along the plantar fascia. In the achilles-tendon stretching group, the stretch was performed in a standing position and to be performed immediately after getting out of bed in the morning. A shoe insert was placed under the affected foot, and the affected leg was placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee was then bent, keeping the back knee straight and heel on the ground. Both stretches for both groups were to be held 10 secondes for 10 repetitions, 3 times a day. The results indicated that both groups improved but the planta fascia specific stretching was superior. The protocol was linked to the use of dorsiflexion night splints that incorporate toe dorsiflexion, but reported the stretching program had advantages over night splints.

Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999 Apr;20(4):214-21.

Abstract

Fifteen centers for orthopaedic treatment of the foot and ankle participated in a prospective randomized trial to compare several nonoperative treatments for proximal plantar fasciitis (heel pain syndrome). Included were 236 patients (160 women and 76 men) who were 16 years of age or older. Most reported duration of symptoms of 6 months or less. Patients with systemic disease, significant musculoskeletal complaints, sciatica, or local nerve entrapment were excluded. We randomized patients prospectively into five different treatment groups. All groups performed Achilles tendon- and plantar fascia-stretching in a similar manner. One group was treated with stretching only. The other four groups stretched and used one of four different shoe inserts, including a silicone heel pad, a felt pad, a rubber heel cup, or a custom-made polypropylene orthotic device. Patients were reevaluated after 8 weeks of treatment. The percentages improved in each group were: (1) silicone insert, 95%; (2) rubber insert, 88%; (3) felt insert, 81%; (4)stretching only, 72%; and (5) custom orthosis, 68%. Combining all the patients who used a prefabricated insert, we found that their improvement rates were higher than those assigned to stretching only (P = 0.022) and those who stretched and used a custom orthosis (P = 0.0074). We conclude that, when used in conjunction with a stretching program, a prefabricated shoe insert is more likely to produce improvement in symptoms as part of the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis than a custom polypropylene orthotic device.

Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006 Jun;40(6):545-9; discussion 549. Epub 2006 Feb 17.

OBJECTIVES: To determine if, in the short term, acetic acid and dexamethasone iontophoresis combined with LowDye (low-Dye) taping are effective in treating the symptoms of plantar fasciitis. METHODS: A double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled trial of 31 patients with medial calcaneal origin plantar fasciitis recruited from three sports medicine clinics. All subjects received six treatments of iontophoresis to the site of maximum tenderness on the plantar aspect of the foot over a period of two weeks, continuous LowDye taping during this time, and instructions on stretching exercises for the gastrocnemius/soleus. They received 0.4% dexamethasone, placebo (0.9% NaCl), or 5% acetic acid. Stiffness and pain were recorded at the initial session, the end of six treatments, and the follow up at four weeks. RESULTS: Data for 42 feet from 31 subjects were used in the study. After the treatment phase, all groups showed significant improvements in morning pain, average pain, and morning stiffness. However for morning pain, the acetic acid/taping group showed a significantly greater improvement than the dexamethasone/taping intervention. At the follow up, the treatment effect of acetic acid/taping and dexamethasone/taping remained significant for symptoms of pain. In contrast, only acetic acid maintained treatment effect for stiffness symptoms compared with placebo (p = 0.031) and dexamethasone. CONCLUSIONS: Six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping gave greater relief from stiffness symptoms than, and equivalent relief from pain symptoms to, treatment with dexamethasone/taping. For the best clinical results at four weeks, taping combined with acetic acid is the preferred treatment option compared with taping combined with dexamethasone or saline iontophoresis.

Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Dec 1;72(11):2237-42.

Plantar fasciitis causes heel pain in active as well as sedentary adults of all ages. The condition is more likely to occur in persons who are obese or in those who are on their feet most of the day. A diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is based on the patient's history and physical findings. The accuracy of radiologic studies in diagnosing plantar heel pain is unknown. Most interventions used to manage plantar fasciitis have not been studied adequately; however, shoe inserts, stretching exercises, steroid injection, and custom-made night splints may be beneficial. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy may effectively treat runners with chronic heel pain but is ineffective in other patients. Limited evidence suggests that casting or surgery may be beneficial when conservative measures fail.

Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1305-10.

BACKGROUND: Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common foot complaints. It is often treated with foot orthoses; however, studies of the effects of orthoses are generally of poor quality, and to our knowledge, no trials have investigated long-term effectiveness. The aim of this trial was to evaluate the short- and long-term effectiveness of foot orthoses in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. METHODS: A pragmatic, participant-blinded, randomized trial was conducted from April 1999 to July 2001. The duration of follow-up for each participant was 12 months. One hundred and thirty-five participants with plantar fasciitis from the local community were recruited to a university-based clinic and were randomly allocated to receive a sham orthosis (soft, thin foam), a prefabricated orthosis (firm foam), or a customized orthosis (semirigid plastic). RESULTS: After 3 months of treatment, estimates of effects on pain and function favored the prefabricated and customized orthoses over the sham orthoses, although only the effects on function were statistically significant. Compared with sham orthoses, the mean pain score (scale, 0-100) was 8.7 points better for the prefabricated orthoses (95% confidence interval, -0.1 to 17.6; P = .05) and 7.4 points better for the customized orthoses (95% confidence interval, -1.4 to 16.2; P = .10). Compared with sham orthoses, the mean function score (scale, 0-100) was 8.4 points better for the prefabricated orthoses (95% confidence interval, 1.0-15.8; P = .03) and 7.5 points better for the customized orthoses (95% confidence interval, 0.3-14.7; P = .04). There were no significant effects on primary outcomes at the 12-month review. CONCLUSIONS: Foot orthoses produce small short-term benefits in function and may also produce small reductions in pain for people with plantar fasciitis, but they do not have long-term beneficial effects compared with a sham device. The customized and prefabricated orthoses used in this trial have similar effectiveness in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Urovitz EP, Birk-Urovitz A, Birk-Urovitz E. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain. Can J Surg. 2008 Aug;51(4):281-3

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate endoscopic plantar fasciotomy for the treatment of recalcitrant heel pain. METHOD: We undertook a retrospective study of the use of endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain that was unresponsive to conservative treatment. Over a 10-year period, we reviewed the charts of 55 patients with a minimum 12-month history of heel pain that failed to respond to standard nonoperative methods and had undergone the procedure described. All patients were clinically reviewed and completed a questionnaire based on the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score for ankle and hindfoot. RESULTS: The mean follow-up was 18 months. The mean preoperative AOFAS score was 66.5; the mean postoperative AOFAS score was 88.2. The mean preoperative pain score was 18.6; the mean postoperative pain score was 31.1. Complications were minimal (2 superficial wound infections). Overall, results were favourable in over 80% of patients. CONCLUSION: We conclude that endoscopic plantar fasciotomy is a reasonable option in the treatment of chronic heel pain that fails to respond to a trial of conservative treatment.

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Young B, Walker MJ, Strunce J et al. A combined treatment approach emphasizing impairment-based manual physical therapy for plantar heal pain: a case series. JOSPT. 2004;34:725-733.

In a case series by B Young et al, they described an impairment-based physcial therapy treatment approach for 4 patients with plantar heel pain. All patients received manual therapy, consisting of posterior talocrural joint mobs and subtalar joint distraction manipulation, in combination with calf-stretching, plantar fascia stretching, and self-anterior-posterior ankle mobilization as a home program. They demonstrated complete pain relief and full return to activities with an average of 2-6 treatments per case.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

EmbedVideo is missing a required parameter.

|

EmbedVideo is missing a required parameter.

|

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1houoX_LGC305ro2l-cEh_uDPlVE-LuIbL2pcsEP2W6Il42kL|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

- Labovitz J et al; The Role of Hamstring Tightness in Plantar Fasciitis; Foot Ankle Spec. 2011 Mar 2. [Epub ahead of print]

Read 4 Credit[edit | edit source]

|

Would you like to earn certification to prove your knowledge on this topic? All you need to do is pass the quiz relating to this page in the Physiopedia member area.

|

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.