Whiplash Associated Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (46 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

Whiplash is | Whiplash associated disorders (WAD) is the term used to described injuries sustained as a result of sudden acceleration-deceleration movements. It is considered the most common outcome after "noncatastrophic" motor vehicle accidents.<ref>Walton DM, Elliott JM. An Integrated Model of Chronic Whiplash-Associated Disorder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(7):462-71. </ref> The term WAD is often used synonymously with the term Whiplash however whiplash refers to the mechanism of injury rather than the presence of symptoms such as pain, stiffness, muscle spasm and headache, in the absence of a lesion or structural pathology.<ref>Spitzer WO. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining" whiplash" and its management. Spine. 1995;20:1S-73S.</ref><ref name=":19" /> The prognosis of WAD is unknown and unpredictable, some cases remain acute with a full recovery while some progress to chronic with long term pain and disability<ref name=":19" /> Early intervention recommendations are rest, pain relief and basic stretching and stretching exercises.<ref name=":19">Stace R. and Gwilym S. « Whiplash associated disorder: a review of current pain concepts. » Bone & Joint 360, vol. 4, nr. 1. 2015. </ref> | ||

The short video below sums up WAD nicely | |||

{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgMdL7vEga8|width}}<ref>3D4Medical - Cervical Whiplash | Trauma. Available from:https://youtu.be/jgMdL7vEga8 (last accessed 22 April 2020)</ref> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

| Line 13: | Line 17: | ||

*[[Intervertebral_disc|intervertebral discs]] and cartilaginous endplates | *[[Intervertebral_disc|intervertebral discs]] and cartilaginous endplates | ||

*muscles | *muscles | ||

*ligaments: [[Alar_ligaments|Alar ligament]], [[Anterior_atlanto-axial_ligament|Anterior atlanto-axial ligament]], [[Anterior_atlanto-occipital_ligament|Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament]], [[Apical_ligament|Apical ligament,]] [[Anterior_longitudinal_ligament|Anterior longitudinal ligament]], [[ | *ligaments: [[Alar_ligaments|Alar ligament]], [[Anterior_atlanto-axial_ligament|Anterior atlanto-axial ligament]], [[Anterior_atlanto-occipital_ligament|Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament]], [[Apical_ligament|Apical ligament,]] [[Anterior_longitudinal_ligament|Anterior longitudinal ligament]], [[Transverse Ligament of the Atlas|Transverse ligament of the atlas]] | ||

*bones: [[Atlas|Atlas]], [[Axis|Axis]], vertebrae (C3-C7) | *bones: [[Atlas|Atlas]], [[Axis|Axis]], vertebrae (C3-C7) | ||

*nervous systems structures: nerve roots, spinal cord, brain, sympathetic nervous system | *nervous systems structures: nerve roots, spinal cord, brain, sympathetic nervous system | ||

*the vascular system structures: internal carotid and [[Vertebral Artery|vertebral artery]] | *the vascular system structures: internal carotid and [[Vertebral Artery|vertebral artery]] | ||

*adjacent joints: [[ | *adjacent joints: [[TMJ Anatomy|Temporomandibular joint]], thoracic spine, ribs, shoulder complex | ||

*the peripheral | *the peripheral [[Vestibular System|vestibular]] system | ||

[[ | |||

[[Image:Whiplash Injuries.jpg|border|center|frameless|400x400px]] | |||

== | ==Pathology== | ||

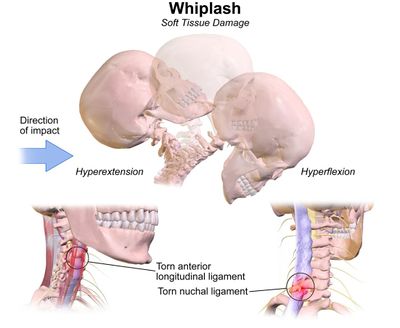

Most WADs are considered to be minor soft tissue-based injuries without evidence of fracture. | |||

The injury occurs in three stages: | |||

* Stage 1: the upper and lower spines experience flexion in stage one | |||

* Stage 2: the spine assumes an S-shape while it begins to extend and eventually straighten to make the neck lordotic again. | |||

* Stage 3: shows the entire spine in extension with an intense sheering force that causes compression of the facet joint capsules. | |||

Studies with cadavers have shown the whiplash injury is the formation of the S-shaped curvature of the cervical spine which induced hyperextension on the lower end of the spine and flexion of the upper levels, which exceeds the physiologic limits of spinal mobility. | |||

== | The Quebec Task Force classifies patients with WAD (whiplash), based on the severity of signs and symptoms, as follows: | ||

# Grade 1 the patient complains of neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness with no positive findings on physical exam. | |||

# Grade 2 the patient exhibits musculoskeletal signs including decreased range of motion and point tenderness. | |||

# Grade 3 the patient also shows neurologic signs that may include sensory deficits, decreased deep tendon reflexes, muscle weakness. | |||

# Grade 4 the patient shows a fracture<ref name=":41">Bragg KJ, Varacallo M. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541016/ Cervical (Whiplash) Sprain.] InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Apr 10. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541016/ (last accessed 2.2.2020)</ref>. | |||

== Etiology == | |||

Whiplash-associated disorders describe a range of neck-related clinical symptoms following an MVA or acceleration-deceleration injury. The pathophysiology underpinning this disorder is still not fully understood and many theories exist. Some of the symptoms are thought to be caused by injury to the following structures: | |||

* Cervical Spine Facet Joint Capsule | |||

* The facet joints | |||

* Spinal ligaments | |||

* Nerve roots | |||

* Intervertebral discs | |||

* Cartilage | |||

* Paraspinal muscles causing spasms | |||

* Intraarticular meniscus.<ref name=":41" /> | |||

WAD is | === Epidemiology === | ||

The most common cause of WAD is MVAs, but it also occurs as a result of sporting injuries and falls. A study by Holm et al suggested that the numbers reporting symptoms has grown increasingly in recent years; in their paper published in 2008 they suggested that the incidence in North Ameria and Europe is approximately 300 per 100,000 inhabitants<ref>Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Guzman J, Peloso P, Nordin M, Hurwitz E, van der Velde G, Carragee E. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2009 Feb 1;32(2):S61-9.</ref>. In the UK the introduction of the compulsory wearing of seatbelts in 1983, an initiative to save deaths on the road, actually led to an increase in the number of reported WADs in the years<ref>Minton R, Murray P, Stephenson W, Galasko CS. Whiplash injury—are current head restraints doing their job?. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2000 Mar 1;32(2):177-85.</ref>. It is also more common in women than men with almost two-thirds of women experiencing symptoms and several studies found that women tended to a slower or incomplete recovery.compared to men<ref>Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, Van Der Velde G, Peloso PM. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2009 Feb 1;32(2):S97-107.</ref>. | |||

The risk that patients develop WAD after an accident with acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer of the neck depends on a variety of factors: | The risk that patients develop WAD after an accident with acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer of the neck depends on a variety of factors: | ||

* | * Severity of the impact, however, it is difficult to obtain objective evidence to confirm this<ref name=":7">HOLM L.W. (2008). The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in Whiplash-Associated Disorders After Traffic Collisions: Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000 –2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Eur Spine J., 17(Suppl 1), pp. 52–59.</ref>. | ||

* | * Neck pain present before the accident is a risk factor for acute neck pain after collision<ref name=":8">Loppolo F. et al. (2014). Epidemiology of Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Springer-Verlag Italia.</ref>. | ||

* | * Women seem to be slightly more at risk of developing WAD. | ||

* Age is also important; younger people (18-23) are more likely to file insurance claims and/or are at greater risk of being treated for WAD<ref name=":1">Cassidy JD. et al. (2000). Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med., 342(16), pp. 1179-86</ref><ref name=":9">McClune T. et al. (2002). Whiplash associated disorders: a review of the literature to guide patient information and advice. Emerg Med J,19, pp 499–506 </ref>. | * Age is also important; younger people (18-23) are more likely to file insurance claims and/or are at greater risk of being treated for WAD<ref name=":1">Cassidy JD. et al. (2000). Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med., 342(16), pp. 1179-86</ref><ref name=":9">McClune T. et al. (2002). Whiplash associated disorders: a review of the literature to guide patient information and advice. Emerg Med J,19, pp 499–506 </ref>. | ||

The number of people worldwide who suffer from chronic pain is between 2 and 58% but lies mainly between 20 and 40%<ref name=":8" />. | |||

* If a patient still has symptoms 3 months after the accident they are likely to remain symptomatic for at least two years, and possibly for much longer<ref name=":9" />. | |||

* 50% of people with injury from whiplash will have a full recovery, | |||

* 25% may have mild levels of disability and the rest moderate to severe pain and disability<ref name=":38">Ritchie C, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J, Sterling M. Derivation of a clinical prediction rule to identify both chronic moderate/severe disability and full recovery following whiplash injury. PAIN®. 2013 Oct 1;154(10):2198-206. Available from: http://www.udptclinic.com/journalclub/sojc/13-14/November/Ritchie%202013.pdf [Accessed 23 March 2018]</ref> | |||

There are many prognostic factors that determine the evolution of WAD and the likelihood that it will evolve into chronic pain. | There are many prognostic factors that determine the evolution of WAD and the likelihood that it will evolve into chronic pain. | ||

*It has been found that a poor expectation of recovery, passive coping strategies, and post-traumatic stress symptoms are associated with chronic neck pain and / or disability after whiplash<ref>Campbell L, Smith A, McGregor L, Sterling M. Psychological Factors and the Development of Chronic Whiplash-associated Disorder(s): A Systematic Review. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(8):755-68.</ref> | |||

*Pre-collision self-reported unspecified pain, high psychological distress, female gender and low educational level predicted future self-reported neck pain<ref name=":2">Algers G. et al. Surgery for chronic symptoms after whiplash injury. Follow-up of 20 cases: Acta Orthop Scand. 1993 vol. 64, nr. 6 p. 654-6</ref>. | *Pre-collision self-reported unspecified pain, high psychological distress, female gender and low educational level predicted future self-reported neck pain<ref name=":2">Algers G. et al. Surgery for chronic symptoms after whiplash injury. Follow-up of 20 cases: Acta Orthop Scand. 1993 vol. 64, nr. 6 p. 654-6</ref>. | ||

* | *history of previous neck pain, baseline neck pain intensity greater than 55/100, presence of neck pain at baseline, presence of headache at baseline, catastrophising, WAD grade 2 or 3, and no seat belt in use at the time of collision<ref>Walton D.M. (2009). Risk Factors for Persistent Problems Following Whiplash Injury: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 39(5), pp. 334–350.</ref>.<ref name=":38" /> | ||

*If the patient was out of work before the accident, sick-listed, or had social assistance | *If the patient was out of work before the accident, sick-listed, or had social assistance<ref name=":2" />. | ||

*Baseline disability has a strong association with chronic disability, but psychological and behavioural factors are also important<ref>Williamson E. et al. (2015). Risk factors for chronic disability in a cohort of patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders seeking physiotherapy treatment for persisting symptoms. Physiotherapy., 101(1), pp.34-43</ref>. | *Baseline disability has a strong association with chronic disability, but psychological and behavioural factors are also important<ref>Williamson E. et al. (2015). Risk factors for chronic disability in a cohort of patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders seeking physiotherapy treatment for persisting symptoms. Physiotherapy., 101(1), pp.34-43</ref>. | ||

*Cold pain threshold, neck ROM, headache, posttraumatic stress symptoms, hyperarousal symptoms (PDS), initial high Neck Disability Index (NDI)<ref name=":38" /> | *Cold pain threshold, neck ROM, headache, posttraumatic stress symptoms, hyperarousal symptoms (PDS), initial high Neck Disability Index (NDI)<ref name=":38" /> | ||

== Whiplash Clinical Prediction Rule == | == Whiplash Clinical Prediction Rule == | ||

A Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR) is a tool that helps to predict outcome for example the possibility of a person to have moderate/severe pain and disability or have full recovery after a whiplash injury.<ref name=":38" /> CPRs are used mostly in the following circumstances:<ref name=":38" /> | A Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR) is a tool that helps to predict the outcome, for example, the possibility of a person to have moderate/severe pain and disability or have full recovery after a whiplash injury.<ref name=":38" /> CPRs are used mostly in the following circumstances:<ref name=":38" /> | ||

* | * Complex decision-making | ||

* | * Uncertainty | ||

* | * Cost-saving possibilities with no compromise to patient care | ||

The CPR for WAD suggests the following:<ref name=":38" /> | The CPR for WAD suggests the following:<ref name=":38" /> | ||

* Probability for chronic moderate/severe disability with older age (≥35), initial high levels of neck disability (NDI≥40) and symptoms of hyperarousal | * Probability for chronic moderate/severe disability with older age (≥35), initial high levels of neck disability (NDI≥40) and symptoms of hyperarousal | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

[https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fars.els-cdn.com%2Fcontent%2Fimage%2F1-s2.0-S0304395913003679-gr2.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%2Fscience%2Farticle%2Fpii%2FS0304395913003679&docid=zt09KEyZerTE2M&tbnid=de0Nfn_QgmGEIM%3A&vet=1&w=578&h=376&client=firefox-b-1-ab&bih=1006&biw=1920&ved=2ahUKEwjL7M6frYPaAhVNba0KHdV2DlcQxiAoAXoECAAQFQ&iact=c&ictx=1 Clinical Prediction Rule Algorithm] | [https://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fars.els-cdn.com%2Fcontent%2Fimage%2F1-s2.0-S0304395913003679-gr2.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sciencedirect.com%2Fscience%2Farticle%2Fpii%2FS0304395913003679&docid=zt09KEyZerTE2M&tbnid=de0Nfn_QgmGEIM%3A&vet=1&w=578&h=376&client=firefox-b-1-ab&bih=1006&biw=1920&ved=2ahUKEwjL7M6frYPaAhVNba0KHdV2DlcQxiAoAXoECAAQFQ&iact=c&ictx=1 Clinical Prediction Rule Algorithm] | ||

Ritchie et al found this CPR to be reproducible and accurate when used following whiplash due to a motor vehicle collision<ref>Ritchie C, Hendrikz J, Jull G, Elliott J, Sterling M. External validation of a clinical prediction rule to predict full recovery and ongoing moderate/severe disability following acute whiplash injury. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Apr;45(4):242-50. Available from: http://www.journalofphysiotherapy.com/article/S1836-9553(16)00015-1/fulltext [Accessed 23 March 2018]</ref> | Ritchie et al found this CPR to be reproducible and accurate when used following whiplash due to a motor vehicle collision<ref>Ritchie C, Hendrikz J, Jull G, Elliott J, Sterling M. External validation of a clinical prediction rule to predict full recovery and ongoing moderate/severe disability following acute whiplash injury. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Apr;45(4):242-50. Available from: http://www.journalofphysiotherapy.com/article/S1836-9553(16)00015-1/fulltext [Accessed 23 March 2018]</ref> Kelly et al explored the agreement between physiotherapists' prognostic risk classification with those of the whiplash CPR and found that the agreement was very low. Physiotherapists tended to be "overly optimistic" about patient outcomes. Kelly et al therefore suggest that the CPR may be beneficial for physiotherapists when assessing patients with whiplash.<ref>Kelly J, Ritchie C, Sterling M. Agreement is very low between a clinical prediction rule and physiotherapist assessment for classifying the risk of poor recovery of individuals with acute whiplash injury. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;39:73-9. </ref> | ||

== Clinical Presentation == | == Clinical Presentation == | ||

Whiplash-associated | Whiplash-associated disorder is a complex condition with varied disturbances in motor, sensorimotor, and sensory functions and psychological distress<ref name=":10">Elliott et al. (2009). Characterization of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 39(5), pp. 312-323</ref><ref>Erbulut DU. (2014). Biomechanics of neck injuries resulting from rear-end vehicle collisions. Turk. Neurosurg., 24(4), pp. 466-470</ref>. The most common symptoms are sub-occipital headache and/or neck pain that is constant or motion-induced<ref name=":11">Ferrari R. et al. (2005). A re-examination of the whiplash associated disorders (WAD) as a systemic illness. Ann Rheum Dis., 64, pp. 1337-1342</ref>. There may be up to 48 hrs delay of symptom onset from the initial injury<ref name=":12">Delfini R. et al. (1999). Delayed post-traumatic cervical instability. Surg Neurol.,51 Pp.588-595.</ref>. | ||

'''Motor Dysfunction''' | |||

* | *Restricted range of motion of the cervical spine. <ref name=":0" /><ref name=":10" />. | ||

* | *Altered patterns of muscle recruitment in both the cervical spine and shoulder girdle regions (clearly a feature of chronic WAD)<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":20">Sterling M. (2004). A proposed new classification system for whiplash associated disorders-implications for assessment and management. Man Ther., 9(2), pp. 60-70.</ref><ref name=":21">Sterling M. et al. (2006). Physical and psychological factors maintain long-term predictive capacity post-whiplash injury. Pain, 122, pp.102-108</ref><ref name=":28">Suissa et al. (2001). The relation between initial symptoms and signs and the prognosis of whiplash. Eur Spine J. 10, pp. 44-49. </ref>. | ||

*Mechanical cervical spine instability<ref name=":12" /> | *Mechanical cervical spine instability<ref name=":12" /> | ||

'''Sensorimotor Dysfunction''' (Greater in patients who also report dizziness due to the neck pain<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":29">Sturzenegger M. et al. (1994). Presenting symptoms and signs after whiplash injury: The influence of accident mechanisms. Neurol., 44, pp. 688–693 </ref><ref name=":27">Van Goethem J. et al. Spinal Imaging: Diagnostic Imaging of the Spine and Spinal Cord. p 258 </ref><ref>Treleaven J. Dizziness, Unsteadiness, Visual Disturbances, and Sensorimotor Control in Traumatic Neck Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(7):492-502.</ref>) | |||

=== Sensorimotor | |||

*Loss of balance | *Loss of balance | ||

*Disturbed neck influenced eye movement control<ref name=":12" /> | *Disturbed neck influenced eye movement control<ref name=":12" /> | ||

'''Sensory Dysfunction: Sensory Hypersensitivity to a Variety of Stimuli''' | |||

* Psychological distress | * Psychological distress | ||

* Post traumatic stress<ref name=":10" /> | * Post-traumatic stress<ref name=":10" /> | ||

* Concentration and memory problems<ref name=":29" /><ref name=":27" /> | * Concentration and memory problems<ref name=":29" /><ref name=":27" /><ref>Beeckmans K, Crunelle C, Van Ingelgom S, Michiels K, Dierckx E, Vancoillie P et al. Persistent cognitive deficits after whiplash injury: a comparative study with mild traumatic brain injury patients and healthy volunteers. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117(2):493-500. </ref> | ||

* Sleep disturbances<ref name=":Daenen">Daenen L, Nijs J, Raadsen B, Roussel N, Cras P, Dankaerts W. Cervical motor dysfunction and its predictive value for long-term recovery in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2013 Feb 5;45(2):113-22. [Accessed 14 June 2018] Available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/mjl/sreh/2013/00000045/00000002/art00001?crawler=true&mimetype=application/pdf </ref> | * Sleep disturbances<ref name=":Daenen">Daenen L, Nijs J, Raadsen B, Roussel N, Cras P, Dankaerts W. Cervical motor dysfunction and its predictive value for long-term recovery in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2013 Feb 5;45(2):113-22. [Accessed 14 June 2018] Available from: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/mjl/sreh/2013/00000045/00000002/art00001?crawler=true&mimetype=application/pdf </ref> | ||

* Anxiety<ref name=":29" /> | * Anxiety<ref name=":29" /> | ||

* Depression<ref name=":29" /> | * Depression<ref name=":29" /> | ||

** Initial depression: | ** Initial depression: associated with greater neck and low back pain severity, numbness/tingling in arms/hands, vision problems, dizziness, fracture<ref name=":22">Phillips LA. Et al. (2010). Whiplash-associated disorders: who gets depressed? Who stays depressed?. Eur. Spine J., 19(6), pp. 945-956 </ref> | ||

** Persistent depression: | ** Persistent depression: associated with older age, greater initial neck and low back pain, post-crash dizziness, anxiety, numbness/tingling, vision and hearing problems<ref name=":22" /> | ||

'''Degeneration of Cervical Muscles''' | |||

* Neck stiffness<ref name=":29" /><ref name=":27" /> | * Neck stiffness<ref name=":29" /><ref name=":27" /> | ||

* Fatty infiltrate may be present in the deep muscles in the suboccipital region and the multifidi may account for some of the functional impairments such as: Proprioceptive deficits, Balance loss, Disturbed motor control of the neck<ref name=":3">BINDER A., The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash, Eura Medicophys 2007, vol. 43, nr. 1, p. 79-89. </ref><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":20" /><ref name=":21" /><ref name=":29" /><ref name=":28" /><ref name=":27" /> | * Fatty infiltrate may be present in the deep muscles in the suboccipital region and the multifidi may account for some of the functional impairments such as: Proprioceptive deficits, Balance loss, Disturbed motor control of the neck<ref name=":3">BINDER A., The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash, Eura Medicophys 2007, vol. 43, nr. 1, p. 79-89. </ref><ref name=":11" /><ref name=":20" /><ref name=":21" /><ref name=":29" /><ref name=":28" /><ref name=":27" /> | ||

'''Other Symptoms''' | |||

The following symptoms may also occur<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":29" /> | The following symptoms may also occur<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":29" /> | ||

*Tinnitus | *Tinnitus | ||

| Line 118: | Line 114: | ||

*Thoracic, temporomandibular, facial, and limb pain | *Thoracic, temporomandibular, facial, and limb pain | ||

It is important to carry out thorough spinal and neurological examinations in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy<ref name=":12" />. Whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash, symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Patients with acute WAD experience widespread pressure hypersensitivity and reduced cervical mobility<ref name=":13">Fernandez Perez AM. et al. (2012). Muscle trigger points, pressure pain threshold, and cervical range of motion in patients with high level of disability related to acute whiplash injury, J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.,42(7), pp. 634-641</ref>. | It is important to carry out thorough spinal and neurological examinations in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy<ref name=":12" />. Whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash, symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Patients with acute WAD experience widespread pressure hypersensitivity and reduced cervical mobility<ref name=":13">Fernandez Perez AM. et al. (2012). Muscle trigger points, pressure pain threshold, and cervical range of motion in patients with high level of disability related to acute whiplash injury, J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.,42(7), pp. 634-641</ref>. Various studies indicate that there can be a spontaneous recovery within 2-3 months<ref>Gargan MF. Et al. (1994).The rate of recovery following whiplash injury. Eur Spine J, 3, pp. 162</ref> According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD (QTF-WAD), 85% of the patients recover within 6 months<ref name=":4">Bekkering GE. et al., KNGF-richtlijn: whiplash. Nederlands tijdschrift voor fysiotherapie nummer 3/jaargang 11</ref>. | ||

In addition, according to a follow-up study by Crutebo et al. (2010), some symptoms were already transient at baseline and symptoms such as neck pain, reduced cervical range of motion, headache, and low back pain, decreased further over the 6 months period. They also investigated the prevalence of depression and found that at baseline this was around 5% in both women and men, whereas post traumatic stress and anxiety were more common in women (19.7% and 11.7%, respectively) compared to men (13.2% and 8.6%). The majority of all reported associated symptoms were mild at both baseline and during follow-up<ref>Crutebo S. et al. (2010). The course of symptoms for whiplash-associated disorders in Sweden: 6-month followup study. J. Rheumatol., 37(7), pp. 1527-33</ref>. | In addition, according to a follow-up study by Crutebo et al. (2010), some symptoms were already transient at baseline and symptoms such as neck pain, reduced cervical range of motion, headache, and low back pain, decreased further over the 6 months period. They also investigated the prevalence of depression and found that at baseline this was around 5% in both women and men, whereas post traumatic stress and anxiety were more common in women (19.7% and 11.7%, respectively) compared to men (13.2% and 8.6%). The majority of all reported associated symptoms were mild at both baseline and during follow-up<ref>Crutebo S. et al. (2010). The course of symptoms for whiplash-associated disorders in Sweden: 6-month followup study. J. Rheumatol., 37(7), pp. 1527-33</ref>. | ||

== | == Evaluation == | ||

The Canadian cervical spine rules or NEXUS criteria are useful for the evaluation of cervical spine injuries in the emergency department. These criteria determine the need for imaging based on the mechanism of injury, physical presentation at the time of the accident, symptomatic presentation in the emergency department, as well as the physical exam. | |||

* The NEXUS c-spine criteria recommend imaging if there is posterior midline cervical-spine tenderness, focal deficits, altered mental status, intoxication or distracting injuries. | |||

* The Canadian c-spine rules define the need for imaging with patients greater than 65 years of age, dangerous mechanism of injury, paresthesia, midline tenderness, immediate onset of neck pain and impaired range of motion. | |||

Additional imaging such as MRI may be necessary for abnormal findings on CT to evaluate for cord injury. Flexion and extension films can help rule out ligamentous injury<ref name=":41" /> | |||

=== | == Clinical Diagnosis == | ||

WAD can be diagnosed based on the mechanism of the injury and clinical presentation of the patient, <ref name=":20" /><ref name=":23">Rodriquez A. et al. (2004). Whiplash: pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve, 29, pp. 768-81. </ref>. There are no specific neuropsychological tests that can diagnose WAD<ref name=":23" />. However, there are several psychological symptoms, as described above, that are associated with WAD. In addition, a whiplash profile has been developed with high scores on sub-scales of somatisation, [[depression]] and obsessive-compulsive behaviour in patients with WAD<ref name=":1" />. | |||

=== Differential Diagnosis === | |||

Includes: | |||

* Cervical spine fracture, | |||

* Carotid artery dissection, | |||

* Herniated disc, | |||

* Spinal cord injury, | |||

* Subluxation of the cervical spine, | |||

* Muscle strain, | |||

* Facet injury, | |||

* Ligamentous injury. | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

== Outcome | |||

* [[Neck_Disability_Index|Neck Disability Index]]<ref name=":4" /><ref>Vernon H. The neck disability index: patient assessment and outcome monitoring in whiplash. Journal of Muskuloskeletal Pain 1996 vol. 4(4): 95-104</ref><ref name=":33">Clinical guidelines for best practice management of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders: Clinical resource guide, TRACsa: Trauma and Injury Recovery, South Australia, Adelaide 2008, p. 46-69.</ref><ref name=":33" /> | * [[Neck_Disability_Index|Neck Disability Index]]<ref name=":4" /><ref>Vernon H. The neck disability index: patient assessment and outcome monitoring in whiplash. Journal of Muskuloskeletal Pain 1996 vol. 4(4): 95-104</ref><ref name=":33">Clinical guidelines for best practice management of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders: Clinical resource guide, TRACsa: Trauma and Injury Recovery, South Australia, Adelaide 2008, p. 46-69.</ref><ref name=":33" /> | ||

* [[Visual_Analogue_Scale|Visual Analogue Scale]] (VAS)<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":33" /> | * [[Visual_Analogue_Scale|Visual Analogue Scale]] (VAS)<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":33" /> | ||

* [[Pain Catastrophizing Scale]] | * [[Pain Catastrophizing Scale]] | ||

* The Whiplash Activity a participation List (WAL)<ref>STENNEBERG MS. et al. « Validation of a new questionnaire to assess the impact of Whiplash Associated Disorders: The Whiplash Activity and participation List (WAL) » Man Ther. vol. 20, nr. 1, p. 84-89, 2015.</ref> | * The Whiplash Activity a participation List (WAL)<ref>STENNEBERG MS. et al. « Validation of a new questionnaire to assess the impact of Whiplash Associated Disorders: The Whiplash Activity and participation List (WAL) » Man Ther. vol. 20, nr. 1, p. 84-89, 2015.</ref> | ||

* Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) in persistent Whiplash<ref>SEE KS. “ Identifying upper limb disability in patients with persistent whiplash. “ Man Ther, vol. 20, nr. 3, p. 487-493, 2015.</ref> | * [[DASH Outcome Measure|Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)]] in persistent Whiplash<ref>SEE KS. “ Identifying upper limb disability in patients with persistent whiplash. “ Man Ther, vol. 20, nr. 3, p. 487-493, 2015.</ref> | ||

* [[SF-36|SF-36]]<ref>ANGST F. et al. (2014). Multidimensional associative factors for improvement in pain, function, and working capacity after rehabilitation of whiplash associated disorder: a prognostic, prospective, outcome study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord., 15, 130.</ref><ref name=":33" /> | * [[36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)|SF-36]]<ref>ANGST F. et al. (2014). Multidimensional associative factors for improvement in pain, function, and working capacity after rehabilitation of whiplash associated disorder: a prognostic, prospective, outcome study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord., 15, 130.</ref><ref name=":33" /> | ||

* Functional Rating Index<ref name=":33" /> | * Functional Rating Index<ref name=":33" /> | ||

* The Self-Efficacy Scale<ref name=":33" /> | * The Self-Efficacy Scale<ref name=":33" /> | ||

* The Coping Strategies Questionnaire<ref name=":33" /> | * The Coping Strategies Questionnaire<ref name=":33" /> | ||

* [[Patient_Specific_Functional_Scale|Patient-Specific Functional Scale]]<ref name=":33" /> | * [[Patient_Specific_Functional_Scale|Patient-Specific Functional Scale]]<ref name=":33" /> | ||

* | * General Health Questionnaire (CHQ) | ||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

| Line 319: | Line 154: | ||

The assessment of individuals with WAD should follow the normal [[Cervical Examination|cervical examination]]. | The assessment of individuals with WAD should follow the normal [[Cervical Examination|cervical examination]]. | ||

=== Subjective | === Subjective === | ||

The subjective history should specifically include information about: | The subjective history should specifically include information about: | ||

* | *Prior history of neck problems (including a previous whiplash) | ||

* | *Prior history of long-term problems (injury and illness) | ||

* | *Current psychosocial problems (family, job-related, financial) | ||

* | *Symptoms (location + time of onset) | ||

* | *Mechanism of injury (e.g. sport, motor vehicle) | ||

=== Objective === | === Objective === | ||

Physical examination is required to identify signs and symptoms and classify WAD according to the QTF-WAD<ref name=":34">Sterling M. (2014). Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). Journal of Physiotherapy, 60, pp. 5–12</ref> | Physical examination is required to identify signs and symptoms and classify WAD according to the QTF-WAD<ref name=":34">Sterling M. (2014). [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955314000058 Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD).] Journal of Physiotherapy, 60, pp. 5–12 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1836955314000058 (last accessed 2.2.2020)</ref>. | ||

During palpation, stiffness and tenderness of the muscles may be observed. These physical symptoms are present in grade 1, 2 and 3. Trigger points may also be observed in grade 2 and 3 WAD. The number of active trigger points may be related to higher neck pain intensity, the number of days since the accident, higher pressure pain hypersensitivity over the cervical spine, and reduced active cervical range of motion<ref name=":13" /> | ==== Inspection and Palpation ==== | ||

During palpation, stiffness and tenderness of the muscles may be observed. These physical symptoms are present in grade 1, 2 and 3. Trigger points may also be observed in grade 2 and 3 WAD. The number of active trigger points may be related to higher neck pain intensity, the number of days since the accident, higher pressure pain hypersensitivity over the cervical spine, and reduced active cervical range of motion<ref name=":13" />. | |||

In grade 1 WAD, there are no physical signs, so there will be no decreased ROM. In grades 2 and 3, a decreased ROM can be identified by testing the neck flexion, extension, rotation and 3D movements<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":34" />. | ==== ROM Testing ==== | ||

In grade 1 WAD, there are no physical signs, so there will be no decreased ROM. In grades 2 and 3, a decreased ROM can be identified by testing the neck flexion, extension, rotation and 3D movements<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":34" />. | |||

To distinguish grade 3 from grade 2, neurological examination is needed. Patients with grade 3 have symptoms of hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli. These can be subjectively reported by patients, and may include allodynia, high irritability of pain, cold sensitivity, and poor sleep due to pain. | ==== Neurological Examination ==== | ||

To distinguish grade 3 from grade 2, a neurological examination is needed. Patients with grade 3 have symptoms of hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli. These can be subjectively reported by patients, and may include allodynia, high irritability of pain, cold sensitivity, and poor sleep due to pain. | |||

Objectively, the results of the neurological examination are hyporeflection, decreased muscles force and sensory deficits in dermatome and myotome. These responses may occur independently of psychological distress. Other physical tests for hypersensitivity include pressure algometers, pain with the application of ice, or increased bilateral responses to the brachial plexus provocation test. | Objectively, the results of the neurological examination are hyporeflection, decreased muscles force and sensory deficits in dermatome and myotome. These responses may occur independently of psychological distress. Other physical tests for hypersensitivity include pressure algometers, pain with the application of ice, or increased bilateral responses to the brachial plexus provocation test. | ||

== Management == | |||

* Education, resumption of normal activity, and mobilization exercises are generally the treatment of choice. | |||

* Ultrasound has also been shown to relieve muscle pain for whiplash-associated disorders. | |||

* First-line treatments include analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, ice, and heat. | |||

* Other controversial analgesic measures include muscle relaxants, which have been shown to have some therapeutic effect in limited studies. | |||

* Biofeedback has also demonstrated effectiveness when used in conjunction with other modalities in acute WAD. | |||

* Injection of lidocaine intramuscularly was also found to relieve pain symptoms. | |||

* Most treatments alone appeared to have moderate effectiveness with combinations of treatment measures improving efficacy and early mobilization consistently most effective<ref name=":41" /> | |||

== Physical Management == | == Physical Management == | ||

The mainstay of management for acute WAD is the provision of advice encouraging return to usual activity and exercise, and this approach is advocated in current clinical guidelines.<ref name=":34" /> | |||

* Management approaches for patients with WAD are poorly researched. | |||

* Often patients do not fit into treatment categories due to multiple factors, and multiple variances which warrant individualised treatment approaches<ref name=":21" />. | |||

* Whiplash-associated disorder is a debilitating and costly condition of at least 6-month duration. | |||

* The majority of patients with whiplash show no physical signs<ref name=":15">Meeus M. et al. Pain Physician. The efficacy of patient education in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. 2012 Sep-Oct;15(5):351-61.</ref> however as many as 50% of victims of WAD grade 1 & 2 will still be experiencing chronic neck pain and disability six months later. A substantial minority develop LWS (late whiplash syndrome), i.e. persistence of significant symptoms beyond 6 months after injury<ref name=":16">Lamb SE. Et al. MINT Study Team. Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial (MINT): design of a randomised controlled trial of treatments for whiplash associated disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007 Jan 26;8:7</ref>. | |||

* The combination of the injury with psychological factors eg poor coping style may lead to chronic WAD<ref name=":24">Seferiadis A. et al. (2004). A review of treatment interventions in whiplash-associated disorders, Eur Spine J, 13 : 387–397 </ref>. | |||

=== Acute Whiplash === | |||

Education provided by physiotherapists or general practitioners is important in preventing chronic whiplash and must be part of the biopsychosocial approach for whiplash patients. The most important goals of the interventions are: | |||

=== Acute | |||

Education provided by physiotherapists or general practitioners is important in preventing | |||

#Reassuring the patient | #Reassuring the patient | ||

#Modulating maladaptive cognition about WAD | #Modulating maladaptive cognition about WAD | ||

#Activating the patient<ref name=":15" />( | #Activating the patient<ref name=":15" /> | ||

* The target of education is removing therapy barriers, enhancing therapy compliance and preventing and treating chronicity<ref name=":15" />. | |||

* For acute WAD verbal education and written advice are helpful (evidence exists that oral information is equally as efficient as an active exercise program)<ref name=":15" />. | |||

* A multidisciplinary programme is best for subacute/chronic patients, with a programme integrating information, exercises and behavioural programmes. | |||

<br>Different types of education include<ref name=":15" />: | |||

#'''Oral Education''': Provide oral education concerning the whiplash mechanisms and emphasising [[Physical Activity and Exercise Prescription|physical activity]] and correct posture. It has a better effect on [[Pain Behaviours|pain]], cervical mobility, and recovery, compared to rest and neck collars. Oral education could be as effective as active physiotherapy and mobilisation. | |||

#'''Educational video''': A brief psycho-educational video shown at the patient's bedside seems to have a profound effect on subsequent pain and medical utilisation in acute whiplash patients, compared to the usual care<ref name=":17">Gross A. et al. Patient education for neck pain. COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS. 2012;3</ref><ref name=":15" /><ref name=":35">Teasell RW. Et al. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): Part 2 – interventions for acute WAD. Pain Res Manage 2010;15(5):295-304</ref>. | |||

Education and information given to the patient must contain the following information: | |||

*Reassurance that prognosis following a whiplash injury is good. | *Reassurance that prognosis following a whiplash injury is good. | ||

*Encouragement to return to normal activities as soon as possible using exercises to facilitate recovery | *Encouragement to return to normal activities as soon as possible using exercises to facilitate recovery | ||

*Reassurance that pain is normal following a whiplash injury and that patients should use analgesia consistently to control this | *Reassurance that pain is normal following a whiplash injury and that patients should use analgesia consistently to control this | ||

*Advice against using a soft collar<ref name=":16" /> | *Advice against using a soft collar<ref name=":16" /> as exercises and/or advice to stay active has shown more favourable outcomes on pain and disability<ref>Christensen SW, Rasmussen MB, Jespersen CL, Sterling M, Skou ST. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2468781221001107 Soft-collar use in rehabilitation of whiplash-associated disorders-A systematic review and meta-analysis.] Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2021 Oct 1;55:102426.</ref> | ||

More studies are required | More studies are required for the type, duration, format, and efficacy of education in the different types of whiplash patients<ref name=":15" /><ref name=":35" />. | ||

Different types of exercise can be considered for WAD | |||

* [[Range of Motion|ROM exercises,]] | |||

* [[McKenzie Method|McKenzie]] exercises | |||

* [[Posture|Postural]] exercises | |||

* [[Strength and Conditioning|Strengthening]] | |||

* [[Motor Control and Learning|Motor control exercises.]] | |||

Active treatment which consists: | |||

* Active mobilisation that is applied gently and over a small ROM, and which is repeated 10 times in each direction, also be given as [[Adherence to Home Exercise Programs|homework]]<ref name=":26">Rosenfeld M. et al.(2000). Early intervention in whiplash-associated disorders: a comparison of two treatment protocols. Spine, vol. 25, nr. 14, p. 1782-7. </ref> | |||

* Home exercise programs in acute WAD including training of neck and shoulder ROM, relaxation and general advice, is sufficient treatment for acute WAD patients when used on a daily basis<ref>Söderlund A. et al. (2000). Acute whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): the effects of early mobilization and prognostic factors in long-term symptomatology. Clin Rehabil. 4(5):457-67.</ref>. | |||

* Strong evidence to suggest that exercise programs and active mobilisation significantly reduce pain in the short term and there is evidence that mobilisation may also improve ROM<ref>Bonk AD. Et al. (2000). Prospective, randomised, controlled study of activity versus collar, and the natural history for whiplash injury, in Germany. World Congress on Whiplash-Associated Disorders in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, February 1999. J Musculoskel Pain 8: 123–132</ref><ref>Conlin A. et al. (2005). Treatment of whiplash-associated disorders-part I: Non-invasive interventions. Pain Res Manag 10(1):21-32.</ref><ref>McKinney LA. (1989). Early mobilisation and outcome in acute sprains of the neck. BMJ 299:1006–1008,</ref><ref>Rosenfeld M. et al.(2003). Active intervention in patients with whiplash-associated disorders improves long-term prognosis. A randomised controlled trial. Spine 28:2491–2498 </ref><ref name=":26" /><ref name=":35" />. | |||

* Spinal manual therapy is often used in the clinical management of neck pain. Systematic reviews of the few trials that have assessed manual therapy techniques alone concluded that manual therapy, such as passive mobilisation, applied to the cervical spine may provide some benefit in reducing pain,<ref name=":34" />. | |||

* Patients with grades 1 and 2 WAD showed good results in a multimodal treatment program including exercises and group therapy, manual therapy, education and exercise. At their 6 months follow-up, 65% of subjects reported a complete return to work, 92% reported a partial or complete return to work, and 81% reported no medical or paramedical treatments over 6 months<ref>Vendrig A. et al. (2000). Results of a multimodal treatment program for patients with chronic symptoms after a whiplash injury of the neck. Spine, 25 (2): p.238–244 (4)</ref> | |||

* The use of a collar stands in contrast with what is indicated in most of the studies; activation, mobilisation and exercise. It is proven that early exercise therapy is superior to collar therapy in reducing pain intensity and disability for whiplash injury. Other studies also showed that exercise therapy gives better pain relief than a soft collar<ref name=":26" /><ref>Schnabel M.et al. (2004). Randomised, controlled outcome study of active mobilisation compared with collar therapy for whiplash injury. Emerg Med J 21:306-310</ref><ref name=":35" />. <br> | |||

=== Chronic Whiplash === | |||

* [[Chronic neck pain|Chronic]] WAD results from a combination of the injury with psychological factors <ref name=":24" /><ref>Aarnio M, Fredrikson M, Lampa E, Sörensen J, Gordh T, Linnman C. [https://journals.lww.com/pain/Fulltext/2022/03000/Whiplash_injuries_associated_with_experienced_pain.11.aspx <nowiki>Whiplash injuries associated with experienced pain and disability can be visualized with [11C]-D-deprenyl positron emission tomography and computed tomography</nowiki>]. Pain. 2022 Mar;163(3):489.</ref> | |||

* Chronic WAD patients report worse health than people with non-specific chronic neck pain<ref>Landén Ludvigsson, M., Peterson, G. and Peolsson, A., 2019. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-018-2004-3 The effect of three exercise approaches on health-related quality of life, and factors associated with its improvement in chronic whiplash-associated disorders: analysis of a randomized controlled trial]. ''Quality of Life Research'', ''28''(2), pp.357-368.</ref> | |||

* A [[Multidisciplinary Care in Pain Management|multidisciplinary therapy]] with cognitive, behavioural therapy and physical therapy, including neck exercises is applied in management of Chronic WAD patients.<ref>Hansen IR. et al. Neck exercises, physical and cognitive behavioural-graded activity as a treatment for adult whiplash patients with chronic neck pain: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC musculoskelet disord. 2011; 12 </ref><ref name=":24" /><ref name=":36">TEASELL RW. Et al., A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 4 - noninvasive interventions for chronic WAD, Pain Res Manag 2010, vol. 15, nr. 5, p. 313-322.</ref> <ref>Björsenius V, Löfgren M, Stålnacke BM. [https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/13/4784/htm One-Year Follow-Up after Multimodal Rehabilitation for Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders.] International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jul;17(13):4784.</ref> It also gives positive results according to the reductions of neck pain and sick leave.<ref name=":24" />. | |||

* Behavioural therapy is used in the therapy as it decreases the patient’s pain intensity in problematic daily activities. ie adapt planning and treatment<ref>SÖDERLUND A. and LINDBERG P., An integrated physiotherapy/cognitive-behavioural approach to the analysis and treatment of chronic whiplash associated disorders, WAD, Disabil Rehabil 2001, vol. 23, nr. 10, p. 436-447. </ref>. | |||

* Exercise programs have a positive result in reducing pain in the short term. Exercise programmes are the most effective noninvasive treatment for patients with chronic WAD and coordination exercises should be added to the treatment to reduce neck pain. | |||

* In patients with chronic WAD, negative thoughts are a very important factor. <ref>Bunketorp L et al. (2006). The perception of pain and pain related cognition in subacute whiplash-associated disorders: its influence on prolonged disability. Disabil Rehabil, 28(5): p.271–279 (2)</ref>. Negative thoughts and pain behaviour can be influenced by specialists and physical therapists by educating patients with chronic WAD on the [[Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)|neurophysiology of pain]].<ref>Van Oosterwijck J. et al. (2011). Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: A pilot study, Journal of rehabilitation research and development, (48) nr.1: p43-58 (3) </ref>. | |||

* Simple advice is equally as effective as a more intense and comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme<ref name=":18">Michaleff ZA. et al., Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial, Lancet. 2014 Jul 12; 384(9938):133-41.</ref>. | |||

* In a study Clinical Biomechanics of [[Posture]] Rehabilitation using mirror-image cervical spine adjustments, exercises and traction to reduce head protrusion and cervical kyphosis. After 5 months, the patient’s chronic WAD symptoms were improved<ref>FERRANTELLI J.R. et al., Conservative Treatment of a patient With Previously Unresponsive Whiplash-Associated Disorders Using Clincal Biomechanics of Posture Rehabilitation Methods, J Manupulative Physiol Ther. 2005, vol. 28, nr. 3, p. 1-8.</ref>.<u></u><u></u><u></u><u></u><u></u><u></u><u></u> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

* For the management of chronic whiplash, there is strong evidence that multidisciplinary therapy is effective. This therapy consists of an exercise program. Early mobilization is most effective when other more serious clinical pathologies noted on examination and imaging diagnostics have been ruled out. | |||

* Prognosis varies secondary to comorbidities prior to the injury, severity of WAD, age and socioeconomic environment. Full recovery has been shown to occur in a few days to several weeks. However, disability can be permanent and range from chronic pain to impaired physical function. | |||

* Though cervical pain is the most common symptom, dizziness and/or [[headache]]<nowiki/>s can be chronic, persistently reported symptoms. Chronic pain, subsequent interference with work, and physical function can cause loss of income and lifestyle. | |||

* Diagnosis and treatment of WAD are complex and associated with many complex issues. Legal environment, prior injury, comorbidity, age, and defensive medicine all play roles in the management and outcomes. There is a large variation in diagnosis and persistence of symptoms depends largely on legal culture or the ability to seek compensation for WAD.<ref name=":41" /> | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

In 2017 Walton and Elliot proposed a new Integrated Model of Chronic WAD. This journal article will explain more on this model | In 2017 Walton and Elliot proposed a new Integrated Model of Chronic WAD. This journal article will explain more on this model | ||

Walton DM, Elliott JM. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2017.7455 An integrated model of chronic whiplash-associated disorder]. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2017 Jul;47(7):462-71. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Cervical Conditions]] | [[Category:Cervical Spine - Conditions]] | ||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Injuries]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

[[Category:Cervical Spine]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:15, 18 November 2022

Original Editor - Hannah Norton

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Okebanama Nelson Onyebuchi, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Tarina van der Stockt, Hannah Norton, Van Horebeek Erika, Sigrid Bortels, Steffen Kistmacher, Anouck Leo, WikiSysop, Rucha Gadgil, 127.0.0.1, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Robin Tacchetti, Joshua Samuel, Ine Van de Weghe and Simisola Ajeyalemi

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Whiplash associated disorders (WAD) is the term used to described injuries sustained as a result of sudden acceleration-deceleration movements. It is considered the most common outcome after "noncatastrophic" motor vehicle accidents.[1] The term WAD is often used synonymously with the term Whiplash however whiplash refers to the mechanism of injury rather than the presence of symptoms such as pain, stiffness, muscle spasm and headache, in the absence of a lesion or structural pathology.[2][3] The prognosis of WAD is unknown and unpredictable, some cases remain acute with a full recovery while some progress to chronic with long term pain and disability[3] Early intervention recommendations are rest, pain relief and basic stretching and stretching exercises.[3]

The short video below sums up WAD nicely

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) affect a variety of anatomical structures of the cervical spine, depending on the force and direction of impact as well as many other factors[5][6][7]. Causes of pain can be any of these tissues, with the strain injury resulting in secondary oedema, haemorrhage, and inflammation:

- joints: zygapophyseal joints, Atlanto-axial joint, Atlanto-occipital joint

- intervertebral discs and cartilaginous endplates

- muscles

- ligaments: Alar ligament, Anterior atlanto-axial ligament, Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament, Apical ligament, Anterior longitudinal ligament, Transverse ligament of the atlas

- bones: Atlas, Axis, vertebrae (C3-C7)

- nervous systems structures: nerve roots, spinal cord, brain, sympathetic nervous system

- the vascular system structures: internal carotid and vertebral artery

- adjacent joints: Temporomandibular joint, thoracic spine, ribs, shoulder complex

- the peripheral vestibular system

Pathology[edit | edit source]

Most WADs are considered to be minor soft tissue-based injuries without evidence of fracture.

The injury occurs in three stages:

- Stage 1: the upper and lower spines experience flexion in stage one

- Stage 2: the spine assumes an S-shape while it begins to extend and eventually straighten to make the neck lordotic again.

- Stage 3: shows the entire spine in extension with an intense sheering force that causes compression of the facet joint capsules.

Studies with cadavers have shown the whiplash injury is the formation of the S-shaped curvature of the cervical spine which induced hyperextension on the lower end of the spine and flexion of the upper levels, which exceeds the physiologic limits of spinal mobility.

The Quebec Task Force classifies patients with WAD (whiplash), based on the severity of signs and symptoms, as follows:

- Grade 1 the patient complains of neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness with no positive findings on physical exam.

- Grade 2 the patient exhibits musculoskeletal signs including decreased range of motion and point tenderness.

- Grade 3 the patient also shows neurologic signs that may include sensory deficits, decreased deep tendon reflexes, muscle weakness.

- Grade 4 the patient shows a fracture[8].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Whiplash-associated disorders describe a range of neck-related clinical symptoms following an MVA or acceleration-deceleration injury. The pathophysiology underpinning this disorder is still not fully understood and many theories exist. Some of the symptoms are thought to be caused by injury to the following structures:

- Cervical Spine Facet Joint Capsule

- The facet joints

- Spinal ligaments

- Nerve roots

- Intervertebral discs

- Cartilage

- Paraspinal muscles causing spasms

- Intraarticular meniscus.[8]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The most common cause of WAD is MVAs, but it also occurs as a result of sporting injuries and falls. A study by Holm et al suggested that the numbers reporting symptoms has grown increasingly in recent years; in their paper published in 2008 they suggested that the incidence in North Ameria and Europe is approximately 300 per 100,000 inhabitants[9]. In the UK the introduction of the compulsory wearing of seatbelts in 1983, an initiative to save deaths on the road, actually led to an increase in the number of reported WADs in the years[10]. It is also more common in women than men with almost two-thirds of women experiencing symptoms and several studies found that women tended to a slower or incomplete recovery.compared to men[11].

The risk that patients develop WAD after an accident with acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer of the neck depends on a variety of factors:

- Severity of the impact, however, it is difficult to obtain objective evidence to confirm this[12].

- Neck pain present before the accident is a risk factor for acute neck pain after collision[13].

- Women seem to be slightly more at risk of developing WAD.

- Age is also important; younger people (18-23) are more likely to file insurance claims and/or are at greater risk of being treated for WAD[14][15].

The number of people worldwide who suffer from chronic pain is between 2 and 58% but lies mainly between 20 and 40%[13].

- If a patient still has symptoms 3 months after the accident they are likely to remain symptomatic for at least two years, and possibly for much longer[15].

- 50% of people with injury from whiplash will have a full recovery,

- 25% may have mild levels of disability and the rest moderate to severe pain and disability[16]

There are many prognostic factors that determine the evolution of WAD and the likelihood that it will evolve into chronic pain.

- It has been found that a poor expectation of recovery, passive coping strategies, and post-traumatic stress symptoms are associated with chronic neck pain and / or disability after whiplash[17]

- Pre-collision self-reported unspecified pain, high psychological distress, female gender and low educational level predicted future self-reported neck pain[18].

- history of previous neck pain, baseline neck pain intensity greater than 55/100, presence of neck pain at baseline, presence of headache at baseline, catastrophising, WAD grade 2 or 3, and no seat belt in use at the time of collision[19].[16]

- If the patient was out of work before the accident, sick-listed, or had social assistance[18].

- Baseline disability has a strong association with chronic disability, but psychological and behavioural factors are also important[20].

- Cold pain threshold, neck ROM, headache, posttraumatic stress symptoms, hyperarousal symptoms (PDS), initial high Neck Disability Index (NDI)[16]

Whiplash Clinical Prediction Rule[edit | edit source]

A Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR) is a tool that helps to predict the outcome, for example, the possibility of a person to have moderate/severe pain and disability or have full recovery after a whiplash injury.[16] CPRs are used mostly in the following circumstances:[16]

- Complex decision-making

- Uncertainty

- Cost-saving possibilities with no compromise to patient care

The CPR for WAD suggests the following:[16]

- Probability for chronic moderate/severe disability with older age (≥35), initial high levels of neck disability (NDI≥40) and symptoms of hyperarousal

- Probability for full recovery with younger age (≤35) and initial low levels of neck disability (NDI≤32)

Clinical Prediction Rule Algorithm

Ritchie et al found this CPR to be reproducible and accurate when used following whiplash due to a motor vehicle collision[21] Kelly et al explored the agreement between physiotherapists' prognostic risk classification with those of the whiplash CPR and found that the agreement was very low. Physiotherapists tended to be "overly optimistic" about patient outcomes. Kelly et al therefore suggest that the CPR may be beneficial for physiotherapists when assessing patients with whiplash.[22]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Whiplash-associated disorder is a complex condition with varied disturbances in motor, sensorimotor, and sensory functions and psychological distress[23][24]. The most common symptoms are sub-occipital headache and/or neck pain that is constant or motion-induced[25]. There may be up to 48 hrs delay of symptom onset from the initial injury[26].

Motor Dysfunction

- Restricted range of motion of the cervical spine. [5][23].

- Altered patterns of muscle recruitment in both the cervical spine and shoulder girdle regions (clearly a feature of chronic WAD)[23][27][28][29].

- Mechanical cervical spine instability[26]

Sensorimotor Dysfunction (Greater in patients who also report dizziness due to the neck pain[23][30][31][32])

- Loss of balance

- Disturbed neck influenced eye movement control[26]

Sensory Dysfunction: Sensory Hypersensitivity to a Variety of Stimuli

- Psychological distress

- Post-traumatic stress[23]

- Concentration and memory problems[30][31][33]

- Sleep disturbances[34]

- Anxiety[30]

- Depression[30]

- Initial depression: associated with greater neck and low back pain severity, numbness/tingling in arms/hands, vision problems, dizziness, fracture[35]

- Persistent depression: associated with older age, greater initial neck and low back pain, post-crash dizziness, anxiety, numbness/tingling, vision and hearing problems[35]

Degeneration of Cervical Muscles

- Neck stiffness[30][31]

- Fatty infiltrate may be present in the deep muscles in the suboccipital region and the multifidi may account for some of the functional impairments such as: Proprioceptive deficits, Balance loss, Disturbed motor control of the neck[36][25][27][28][30][29][31]

Other Symptoms

The following symptoms may also occur[26][30]

- Tinnitus

- Malaise

- Disequilibrium/Dizziness

- Thoracic, temporomandibular, facial, and limb pain

It is important to carry out thorough spinal and neurological examinations in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy[26]. Whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash, symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Patients with acute WAD experience widespread pressure hypersensitivity and reduced cervical mobility[37]. Various studies indicate that there can be a spontaneous recovery within 2-3 months[38] According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD (QTF-WAD), 85% of the patients recover within 6 months[39].

In addition, according to a follow-up study by Crutebo et al. (2010), some symptoms were already transient at baseline and symptoms such as neck pain, reduced cervical range of motion, headache, and low back pain, decreased further over the 6 months period. They also investigated the prevalence of depression and found that at baseline this was around 5% in both women and men, whereas post traumatic stress and anxiety were more common in women (19.7% and 11.7%, respectively) compared to men (13.2% and 8.6%). The majority of all reported associated symptoms were mild at both baseline and during follow-up[40].

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

The Canadian cervical spine rules or NEXUS criteria are useful for the evaluation of cervical spine injuries in the emergency department. These criteria determine the need for imaging based on the mechanism of injury, physical presentation at the time of the accident, symptomatic presentation in the emergency department, as well as the physical exam.

- The NEXUS c-spine criteria recommend imaging if there is posterior midline cervical-spine tenderness, focal deficits, altered mental status, intoxication or distracting injuries.

- The Canadian c-spine rules define the need for imaging with patients greater than 65 years of age, dangerous mechanism of injury, paresthesia, midline tenderness, immediate onset of neck pain and impaired range of motion.

Additional imaging such as MRI may be necessary for abnormal findings on CT to evaluate for cord injury. Flexion and extension films can help rule out ligamentous injury[8]

Clinical Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

WAD can be diagnosed based on the mechanism of the injury and clinical presentation of the patient, [27][41]. There are no specific neuropsychological tests that can diagnose WAD[41]. However, there are several psychological symptoms, as described above, that are associated with WAD. In addition, a whiplash profile has been developed with high scores on sub-scales of somatisation, depression and obsessive-compulsive behaviour in patients with WAD[14].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Includes:

- Cervical spine fracture,

- Carotid artery dissection,

- Herniated disc,

- Spinal cord injury,

- Subluxation of the cervical spine,

- Muscle strain,

- Facet injury,

- Ligamentous injury.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Neck Disability Index[39][42][43][43]

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)[39][43]

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- The Whiplash Activity a participation List (WAL)[44]

- Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) in persistent Whiplash[45]

- SF-36[46][43]

- Functional Rating Index[43]

- The Self-Efficacy Scale[43]

- The Coping Strategies Questionnaire[43]

- Patient-Specific Functional Scale[43]

- General Health Questionnaire (CHQ)

Examination[edit | edit source]

The assessment of individuals with WAD should follow the normal cervical examination.

Subjective[edit | edit source]

The subjective history should specifically include information about:

- Prior history of neck problems (including a previous whiplash)

- Prior history of long-term problems (injury and illness)

- Current psychosocial problems (family, job-related, financial)

- Symptoms (location + time of onset)

- Mechanism of injury (e.g. sport, motor vehicle)

Objective[edit | edit source]

Physical examination is required to identify signs and symptoms and classify WAD according to the QTF-WAD[47].

Inspection and Palpation[edit | edit source]

During palpation, stiffness and tenderness of the muscles may be observed. These physical symptoms are present in grade 1, 2 and 3. Trigger points may also be observed in grade 2 and 3 WAD. The number of active trigger points may be related to higher neck pain intensity, the number of days since the accident, higher pressure pain hypersensitivity over the cervical spine, and reduced active cervical range of motion[37].

ROM Testing[edit | edit source]

In grade 1 WAD, there are no physical signs, so there will be no decreased ROM. In grades 2 and 3, a decreased ROM can be identified by testing the neck flexion, extension, rotation and 3D movements[37][47].

Neurological Examination[edit | edit source]

To distinguish grade 3 from grade 2, a neurological examination is needed. Patients with grade 3 have symptoms of hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli. These can be subjectively reported by patients, and may include allodynia, high irritability of pain, cold sensitivity, and poor sleep due to pain.

Objectively, the results of the neurological examination are hyporeflection, decreased muscles force and sensory deficits in dermatome and myotome. These responses may occur independently of psychological distress. Other physical tests for hypersensitivity include pressure algometers, pain with the application of ice, or increased bilateral responses to the brachial plexus provocation test.

Management[edit | edit source]

- Education, resumption of normal activity, and mobilization exercises are generally the treatment of choice.

- Ultrasound has also been shown to relieve muscle pain for whiplash-associated disorders.

- First-line treatments include analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, ice, and heat.

- Other controversial analgesic measures include muscle relaxants, which have been shown to have some therapeutic effect in limited studies.

- Biofeedback has also demonstrated effectiveness when used in conjunction with other modalities in acute WAD.

- Injection of lidocaine intramuscularly was also found to relieve pain symptoms.

- Most treatments alone appeared to have moderate effectiveness with combinations of treatment measures improving efficacy and early mobilization consistently most effective[8]

Physical Management[edit | edit source]

The mainstay of management for acute WAD is the provision of advice encouraging return to usual activity and exercise, and this approach is advocated in current clinical guidelines.[47]

- Management approaches for patients with WAD are poorly researched.

- Often patients do not fit into treatment categories due to multiple factors, and multiple variances which warrant individualised treatment approaches[28].

- Whiplash-associated disorder is a debilitating and costly condition of at least 6-month duration.

- The majority of patients with whiplash show no physical signs[48] however as many as 50% of victims of WAD grade 1 & 2 will still be experiencing chronic neck pain and disability six months later. A substantial minority develop LWS (late whiplash syndrome), i.e. persistence of significant symptoms beyond 6 months after injury[49].

- The combination of the injury with psychological factors eg poor coping style may lead to chronic WAD[50].

Acute Whiplash[edit | edit source]

Education provided by physiotherapists or general practitioners is important in preventing chronic whiplash and must be part of the biopsychosocial approach for whiplash patients. The most important goals of the interventions are:

- Reassuring the patient

- Modulating maladaptive cognition about WAD

- Activating the patient[48]

- The target of education is removing therapy barriers, enhancing therapy compliance and preventing and treating chronicity[48].

- For acute WAD verbal education and written advice are helpful (evidence exists that oral information is equally as efficient as an active exercise program)[48].

- A multidisciplinary programme is best for subacute/chronic patients, with a programme integrating information, exercises and behavioural programmes.

Different types of education include[48]:

- Oral Education: Provide oral education concerning the whiplash mechanisms and emphasising physical activity and correct posture. It has a better effect on pain, cervical mobility, and recovery, compared to rest and neck collars. Oral education could be as effective as active physiotherapy and mobilisation.

- Educational video: A brief psycho-educational video shown at the patient's bedside seems to have a profound effect on subsequent pain and medical utilisation in acute whiplash patients, compared to the usual care[51][48][52].

Education and information given to the patient must contain the following information:

- Reassurance that prognosis following a whiplash injury is good.

- Encouragement to return to normal activities as soon as possible using exercises to facilitate recovery

- Reassurance that pain is normal following a whiplash injury and that patients should use analgesia consistently to control this

- Advice against using a soft collar[49] as exercises and/or advice to stay active has shown more favourable outcomes on pain and disability[53]

More studies are required for the type, duration, format, and efficacy of education in the different types of whiplash patients[48][52].

Different types of exercise can be considered for WAD

- ROM exercises,

- McKenzie exercises

- Postural exercises

- Strengthening

- Motor control exercises.

Active treatment which consists:

- Active mobilisation that is applied gently and over a small ROM, and which is repeated 10 times in each direction, also be given as homework[54]

- Home exercise programs in acute WAD including training of neck and shoulder ROM, relaxation and general advice, is sufficient treatment for acute WAD patients when used on a daily basis[55].

- Strong evidence to suggest that exercise programs and active mobilisation significantly reduce pain in the short term and there is evidence that mobilisation may also improve ROM[56][57][58][59][54][52].

- Spinal manual therapy is often used in the clinical management of neck pain. Systematic reviews of the few trials that have assessed manual therapy techniques alone concluded that manual therapy, such as passive mobilisation, applied to the cervical spine may provide some benefit in reducing pain,[47].

- Patients with grades 1 and 2 WAD showed good results in a multimodal treatment program including exercises and group therapy, manual therapy, education and exercise. At their 6 months follow-up, 65% of subjects reported a complete return to work, 92% reported a partial or complete return to work, and 81% reported no medical or paramedical treatments over 6 months[60]

- The use of a collar stands in contrast with what is indicated in most of the studies; activation, mobilisation and exercise. It is proven that early exercise therapy is superior to collar therapy in reducing pain intensity and disability for whiplash injury. Other studies also showed that exercise therapy gives better pain relief than a soft collar[54][61][52].

Chronic Whiplash[edit | edit source]

- Chronic WAD results from a combination of the injury with psychological factors [50][62]

- Chronic WAD patients report worse health than people with non-specific chronic neck pain[63]

- A multidisciplinary therapy with cognitive, behavioural therapy and physical therapy, including neck exercises is applied in management of Chronic WAD patients.[64][50][65] [66] It also gives positive results according to the reductions of neck pain and sick leave.[50].

- Behavioural therapy is used in the therapy as it decreases the patient’s pain intensity in problematic daily activities. ie adapt planning and treatment[67].

- Exercise programs have a positive result in reducing pain in the short term. Exercise programmes are the most effective noninvasive treatment for patients with chronic WAD and coordination exercises should be added to the treatment to reduce neck pain.

- In patients with chronic WAD, negative thoughts are a very important factor. [68]. Negative thoughts and pain behaviour can be influenced by specialists and physical therapists by educating patients with chronic WAD on the neurophysiology of pain.[69].

- Simple advice is equally as effective as a more intense and comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme[70].

- In a study Clinical Biomechanics of Posture Rehabilitation using mirror-image cervical spine adjustments, exercises and traction to reduce head protrusion and cervical kyphosis. After 5 months, the patient’s chronic WAD symptoms were improved[71].

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

- For the management of chronic whiplash, there is strong evidence that multidisciplinary therapy is effective. This therapy consists of an exercise program. Early mobilization is most effective when other more serious clinical pathologies noted on examination and imaging diagnostics have been ruled out.

- Prognosis varies secondary to comorbidities prior to the injury, severity of WAD, age and socioeconomic environment. Full recovery has been shown to occur in a few days to several weeks. However, disability can be permanent and range from chronic pain to impaired physical function.

- Though cervical pain is the most common symptom, dizziness and/or headaches can be chronic, persistently reported symptoms. Chronic pain, subsequent interference with work, and physical function can cause loss of income and lifestyle.

- Diagnosis and treatment of WAD are complex and associated with many complex issues. Legal environment, prior injury, comorbidity, age, and defensive medicine all play roles in the management and outcomes. There is a large variation in diagnosis and persistence of symptoms depends largely on legal culture or the ability to seek compensation for WAD.[8]

Resources[edit | edit source]

In 2017 Walton and Elliot proposed a new Integrated Model of Chronic WAD. This journal article will explain more on this model