Lumbar Spine Fracture

Original Editors - Thomas Albaugh, Elizabeth Record, Misty Hillin and Patrick Bales as part of the Texas State University's Evidence-based Practice project

Lead Editors - Lucy Aird, Lionel Geernaert, Patrick Bales, Thomas Albaugh, Laura Ritchie, Admin, Elizabeth Record, Kim Jackson, Aminat Abolade, Rachael Lowe, Mahyar Firouzi, Wanda van Niekerk, Lucinda hampton, Saud Alghamdi, Jeremy Brady and 127.0.0.1

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

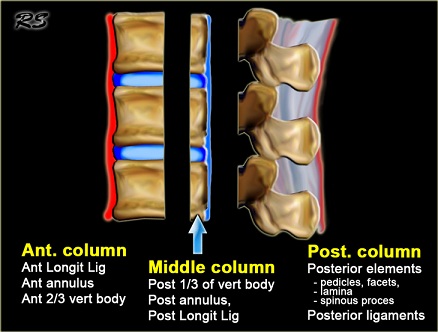

The complex shape of the lumbar vertebrae, along with the interaction of the central nervous system, the relatively specialized structures of the intervertebral disks and the associated vertebral ligaments has made the description and classification of spinal fractures an ongoing pursuit for the medical community. The current system had its roots in 1963 after Holdsworth proposed classifying spinal fractures by the mechanism of injury (MOI) of compression, flexion, extension and flexion-rotation. He divided the injuries according to the involvement of the anterior weight-bearing column and the posterior “tension bearing” column of facet joints and ligament complex.[1] The 1983 Denis system revision led to a center column comprised of the posterior vertebral body, posterior vertebral disk and posterior longitudinal ligament.[2]

In the Denis system, it was believed that trauma focused on the middle column was sufficient to cause instability in the spine. The instability was further categorized into three types:

- First degree: considered mechanical

- Second degree: neurological

- Third degree: combined mechanical/neurological

This system is still currently the favoured method. The main frustration with the Denis method is that the inclusion of the middle column introduced a “virtual landmark” that isn’t really suitable for determining an injury type because it is not an anatomic entity. A recently developed system by Aebi incorporates the two-column method, combined with the method of injury, and the instability which may result in neurological compromise.[3] This method works with grades of severity, increasing from type A to type B and type C. Every type has another subdivision of grade 1 to 3, also going in increasing order of severity. In this way, we have nine basic injury types which can be even further specified into 27 subgroups of spinal fractures[3].[3] Obviously the classification of fractures is complicated and ongoing.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spine fractures, as the name suggests, are always located in the lumbar spine. The lumbar spine is the part of the spine located in the lower back and is a common painful area in physiotherapy. It is situated in between the thoracic and the sacral part of the spine and is characterised by lordosis.

The lumbar spine consists of five vertebrae that are simultaneously strong and articularly flexible to give the ability to move the body in different planes such as flexion-extension, rotation and lateral flexion.

A lumbar vertebra consists of;

- a large anterior body which bears most of the weight that is placed on the spine

- massive dorsal vertebral arches which protect the neural structures (spinal cord) lying inside the vertebral foramen (space between the body and the arches)

- several types of processes, on which many muscles and ligaments attach

- the pedicle and facet joints, which are other weight-bearing structures

In between the vertebrae, there are intervertebral discs, which support the weight-bearing task of the vertebral bodies and act as shock-absorbers. Another function of these discs is that they connect the vertebral bodies to each other.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

“In 2005, osteoporosis was responsible for more than 2 million fractures; approximately 547,000 of those were vertebral fractures. Approximately one-third of osteoporotic vertebral injuries are lumbar, one-third are thoracolumbar, and one-third are thoracic in origin. Additionally, 75% of women older than 65 years who have scoliosis have at least one osteoporotic wedge fracture.”[4] The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons website lists fractures based on the pattern of injury and in a simpler format:

The flexion pattern contains compression fractures and axial burst fractures. The extension pattern, which contains flexion/distraction (often called a chance fracture). The rotation pattern contains transverse process and fracture-dislocation.[5]

Nowadays, fractures are divided into type A, B or C fractures. These are actually the same as the ones described above. Although sufficiently powerful studies about the epidemiology of lumbar spine fractures are lacking, several studies acknowledge osteoporosis as the underlying cause of many lumbar fractures, especially in postmenopausal women.

Cooper et al. found an age-adjusted incidence rate of 117 per 100,000 in women that was almost twice of that in men (73 per 100,000). Of all fractures, 14% followed severe trauma, 83% followed moderate or no trauma and 3% were pathologic. Incidence rates for fractures following moderate trauma were higher in women than in men and rose steeply with age in both genders. In contrast, fractures following severe trauma were more frequent in men, and their incidence increased less with age. One should keep in mind that this study did not specify the localisation (cervical, thoracic, lumbar) and type of fracture.[6]

Type A fractures- compression (flexion pattern):

- Failure of the anterior column to resist compression.

- Burst fractures (Type A3) are the most frequent and severe type of Type A fractures. They are characterised by the increase of the interpedicular distance and the loss of the height of the vertebral body.

- There is another subdivision of A3.1 Incomplete, A3.2 Complete and A3.3 Burst split fractures. The complete burst fracture involves both endplates, the superior one as well as the inferior one.

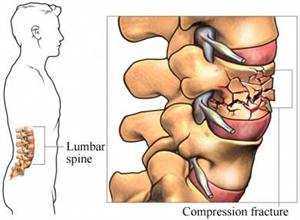

- Compression fractures are usually caused by an axial load on the anterior part of the vertebrae. Due to this vertical force, this specific part of the vertebrae will lose height and will become wedge-shaped.[5]

- Axial Burst fractures are also caused by an axial load on the vertebrae, but the difference with the compression fractures is that the vertebra is crushed in every direction and therefore also spreads out in every direction. This implies that this kind of fracture is far more dangerous than a compression fracture because of the risk of the bony margins injuring the spinal cord. These kinds of fractures are typically seen in motor accidents or falls from heights.[7]

- Burst fractures may result in some retropulsion of the vertebra into the vertebral canal.[7]

Type B fractures- distraction (extension pattern):

- Failure from the posterior column to resist distraction

- B1-lesions are lesions in which the posterior ligament is disrupted but without the involvement of relevant bony elements. The B2-lesions are basically bony seat belt injuries also called Chance fractures. B3-lesions are lesions who are to be found in the anterior column, producing very typical fractures.

- A Chance fracture results from a flexion-distraction movement e.g an emergency car stop in which the force of the seat belt pulls the vertebrae apart. For this reason, chance fractures are also called ‘seatbelt fractures’ and are often associated with intra-abdominal injuries. Chance fractures involve all three spinal columns. The vertebral body suffers a flexion injury while the posterior elements suffer a distraction type injury.[8]

- If this type of injuries remain unnoticed, it may result in progressive kyphosis with pain and deformity.

Type C- rotation:

- Results in disrupted posterior tension banding system and a disruption of the anterior column with a rotational dislocation.[3]

- Transverse process (TP) fractures are uncommon and result from extreme sideways bending. These do not usually affect stability.

- The fracture-dislocation is a fracture in which bone and its accompanying soft tissue will move off an adjacent vertebra. This type is an unstable fracture and may cause severe spinal cord compression.

- “C1 lesion is a rotational injury combined with a typical anterior lesion. The C2 lesion is a rotational injury with a typical B type lesion and the C3-lesion is characterised by multilevel and shear injuries with a big variety and quite rare forms in their appearance.”[3]

Essential characteristics of the three injury types;

- Type A, compression injury of the anterior column.

- Type B, two-column injury with either posterior or anterior transverse disruption.

- Type C, two-column injury with rotation.

Classification A B C (according to M. Aebi, V. Arlet, J.K. Webb, in AO-Manual of Spine Surgery, Vol. I, 2008. Thieme Publisher, Stuttgart)

The analysis of a whole collective of injuries learned us that there is a dominance of the injuries at the thoracolumbar junction with the most frequent fractures at L1, second frequent at T12, third frequent at L2, fourth frequent at L3. Injuries of the T10 and L4 vertebrae are of the same frequency along with injuries of T5, 6, 7 and 8.[3][9]

While the listed examples above all imply trauma for a spinal fracture, osteoporosis and conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta are commonly implicated in vertebral fractures as well.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- History of osteoporosis. [10]

- Use of corticosteroids.[10]

- Severe trauma.[10]

- Females.[10]

- Older Age (> 50 years old).[10]

- History of spinal fractures.[10]

- History of cancer.[10]

- History of falls.[10]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Fractures of the lumbar spine and at the thoracolumbar junction are quite common. Per definition, in compression type fractures the anterior column is affected, whereas in burst fractures, anterior and middle column and sometimes the posterior column, are involved. Compression type fractures are predominately caused by indirect hyperflexion and bending forces whereas burst type fractures result from axial loading.[11]

More than 65% of vertebral fractures may not cause recognizable symptoms and may be undiagnosed with radiographs.[12] Patients could have neurologic involvement, may have low back pain, movement may be impaired, or a combination of all of them. When the spinal cord is also involved, numbness, tingling, weakness, or bowel/bladder dysfunction may occur.[5]

Upon inspection of the spine, the patient typically has a kyphotic posture that cannot be corrected. The kyphosis is caused by the wedge shape of the fractured vertebra; the fracture essentially turns the lateral conformation of the vertebra from a square to a triangle.[13]

A useful tool for the classification of thoracolumbar injuries is ‘the Thoraco-Lumbar Injury Classification and Severity(TLICS) classification system’. Recent studies have raised concerns regarding the reliability of both the Denis and the AO systems, which have been previously mentioned. Both systems have moderate inter- and intra-observer reliability, due to the complex subtypes within each system. This shows that increased complexity of the classification system often leads to less reliability in the clinical setting.

The Thoraco-Lumbar Injury Classification and Severity (TLICS) scale, developed by the Spine Trauma Study Group (STSG), works with three “primary axes”:[14]

- Injury morphology

- Integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex (PLC)

- Neurological status.[14]

The three primary axes are further divided into a limited number of easily recognizable subgroups, further defining a particular injury from least to most significant.[15]

The interpretation of the TLICS severity score is simple. Lesser point values are assigned to the less severe or less urgent injuries and greater point values are assigned to more severe or more urgent injuries. In general, severity is used to indicate the extent of injury to the bony and ligamentous elements of the spine.[16] The TLICS system has proven helpful in guiding surgical treatment. The scores of the three primary axes are summed to yield a total severity score. This score can generally predict the need for surgical intervention. Generally speaking, a total score >5 requires surgical treatment whereas a score <3 can be treated non-operatively.

The reliability and the validity have been investigated extensively. Since the introduction of the classification system it underwent a series of modifications. The most recent version of the system has proven to be both valid and reliable by multiple studies, Rampersaud et al. (2006) performed a multi-center reliability study which shows that the TLISS establishes a consensus-based algorithm for treating thoracolumbar injuries.[17] Patel et al. (2007) also showed the validity of the system in a prospective study.[18] The main goal of this study was to evaluate the time-dependent changes in inter-observer reliability. They found that there was a substantial improvement at the second assessment, this suggests that the classifications system can be taught efficiently. There are even more studies analyzing the reliability and the validity and all show positive results. Therefore we can conclude this system can be incorporated in daily practice.[16]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Coccyx pain

- Lumbar Facet Arthropathy

- Mechanical Low Back Pain ( Non-Specific Low Back Pain)

- Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease - process in which the intervertebral discs of the lumbar region lose height and hydration.

- Lumbar Spondylolysis - a uni- or bilateral bony defect in the pars interarticularis or isthmus of the vertebra

- Golden standard: a combination of SPECT and (CT).

- MRI is a valuable tool for diagnosing as well, as T1-weighted MR images have been proven useful in the early diagnosis of spondylolysis. In addition, MRI allows spondylolysis to be diagnosed without ionizing radiation

- Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

- Osteoporosis - a disease characterized by a decrease in bone density (mass and quality)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

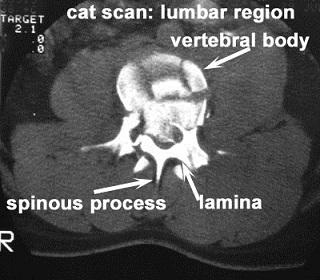

Although historically the golden standard for diagnosing spine fractures has been plain radiography, Spiral Computed Tomography (SCT) is being used with increasing frequency. Computed Tomography is more sensitive than plain radiographs for evaluation of the Thoracolumbar spine after trauma. In addition, Computed Tomography can be performed faster.[19] According to one study by Brown et al. SCT of the spine identified 99.3% of all fractures of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine. Those missed by the SCT required minimal or no treatment. SCT is a sensitive diagnostic test for the identification of spinal fractures.[20]

A more recent study by Ang et al[21] concluded that 3-T Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with thin-slice 3D T1 VIBE is 100% accurate in diagnosing complete pars fractures and has excellent diagnostic ability in the detection and characterisation of incomplete pars stress fractures compared to CT. MRI has the added advantages of detecting bone marrow edema and does not employ ionizing radiation. One disadvantage is that MRI may be substantially more costly than CT for some institutions.[21]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

To assess if the treatment is working or has worked one can take an x-Ray and evaluate the bone mineral density. Subjectively, a therapist notices progression with various tests that determine the ROM and strength. The measurements can also be taken by other tests.

Clinical examination[edit | edit source]

Whilst height loss is normal with aging due to the compression over the years on the intervertebral disks, it can also be an indicator for a fracture of the spine. Without radiographic imaging it is uncertain there is a fracture. Therefore one should take radiographic imaging to be completely certain of a fracture.[22]

When confronted by an acute case of a lumbar fracture the patient needs emergency treatment because the extend of the injury is not known. A doctor should do a full body exam to make sure the fracture did not cause any other damage.

It is of grave importance the doctor performs neurological tests as well as imaging tests. The neurological tests evaluate if the patient has suffered damage to the spinal cord or nerves that originate in the lumbar region. the tests consist of moving, feeling and sensing the limbs in different positions and testing of the reflexes of the patient.

The imaging tests consist of X-rays, CT scans and MRI depending on the extent of the trauma that is suffered.[23]

Radiologists should take a proactive role in helping to diagnose spinal fractures. The failure to diagnose vertebral fracture is a worldwide problem due in part to the lack of fracture recognition by radiologists and the use of ambiguous terminology in radiology reports.[22]

Physical therapists can also be more engaged through a thorough exam that includes:

- A detailed history

- A neurological exam

- Palpation, especially midline along the vertebrae[13]

- ROM, STR, joint mobility and muscle length assessments

- Careful differential diagnosis

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Patients with burst fractures (a type of traumatic spinal injury in which a vertebra breaks from a high-energy vertical axial load) of the thoracic and lumbar spines must receive individualized case analysis before a course of therapy can be decided. A consideration of fracture stability, degree of canal compromise, and patient evaluation become significant in determining operative or nonoperative treatment. In neurologically intact patients with selected fractures, nonoperative treatment can be successful in the functional rehabilitation of the patient.[24]

Operative[edit | edit source]

When neurological impairments are present, surgical procedures are usually required to repair or relieve the site of injury.[25] There are several procedures determined by the degree of compromise, the spinal level of the fracture and the patient's previous health status.[26]

A technique called ‘decompression’ is an example of one of these procedures. In this technique, a small portion of bone or disc material that compresses the nerve root is surgically removed to give the root more space.[27]

Anterior/Posterior Approach:

Often dictated by the severity of compromise or level of injury, a surgeon will make an anterior or posterior approach to the patient's spine in order to stabilize it. Rods, screws and other mechanical devices are inserted through remaining structures to fuse the affected vertebra(e). The anterior approach dominates upper lumbar (L1, L2) fractures due to involvement with the crura of the diaphragm while lower lumbar fractures (L5) are stabilized through a posterior approach method.[28][29]

Kyphoplasty:

A mini-invasive percutaneous procedure that relieves vertebral fracture pain through the heat discharged during bone cement coagulation. The cement also solidifies to further stabilize the site of injury.[30] During the procedure, a cannula is introduced into the vertebral body followed by a bone expander to regain some vertebral height. Kyphoplasty has been found to be similar in success rate as vertebroplasty, but with greater recovery of vertebral height.[31]

A study by Wardlaw et al. suggests that Balloon Kyphoplasty (a minimally invasive procedure for the treatment of painful vertebral fractures) is an effective and safe procedure for patients with acute vertebral fractures.[32]

Vertebroplasty:

An effective treatment in the management of vertebral compression fractures, vertebroplasty involves injecting bone fillers such as polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement into the fractured vertebral body.

The effect of this procedure on osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures was analysed by R. Takemasa et al. and found no demonstrable clinically important benefits compared with a sham procedure.

Non-operative[edit | edit source]

Patients not requiring surgery receive treatments that target pain relief with bracing and rehabilitation therapy.[13][12] Those with compression type and burst type fractures involving the anterior and middle column have been described as the best candidates for non-operative management.[11]

Compression Fractures

A study by Stadhouder et al states that brace treatment with supplementary physical therapy is the treatment in choice for patients with compression fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine.[33]

Burst Fractures

Operative treatment of patients with a stable thoracolumbar burst fracture and normal findings on a neurological examination provides no major long-term advantage compared with nonoperative treatment.[34]

A prospective study by Shen et al. comparing operative and non-operative treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficit acknowledges the early pain relief and partial kyphosis correction provided by operative short-segment posterior fixation, but the functional outcome at two years is similar to that of non-operative treatment.[35]

Orthoses[edit | edit source]

A thoracic-lumbar-sacral orthosis (TLSO) is the current brace of choice for these types of injuries. However, patients will also want to move into mobility as their pain and healing process progresses. Thus allowing them to move into weight-bearing exercises to prevent future osteoporosis and extension exercises.[13][12]

Non-operative options are increasingly becoming the preferred method of fracture management as bracing and therapy methods are shown to be as clinically effective, yet much more cost-efficient than surgical options.[36]

Orthoses have shown great improvements in muscle strength, posture and body height. The brace makes sure that muscles along the vertebrae get less fatigued and relief of muscle spasm. In lumbar fractures orthosis is available but can only restrict sagittal plane motion in the upper lumbar spine (L1-3). Motion between the lower segments has been proven to be increased while wearing an orthosis brace (L4-S1).[37]

Pharmaceutical[edit | edit source]

Medications ranging from Tylenol and NSAIDs to opioids can be taken to modulate lumbar spine fracture pain. Spinal nerve blocks at the L2 region have also been found to be effective against acute low back pain from fractures.[38]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The purpose of physical therapy management in patients with lumbar spine fracture is to decrease pain, increase mobility and prevent future occurrences.[13][12] While mobility is important, back extensor and abdominal (core) strength have been shown an effective therapeutic intervention for those with lumbar problems associated with osteoporosis. In particular, the multifidus, quadratus lumborum and transverse abdominals help support the spine. So much so that increasing strength not only relieves pain and symptoms from those patients with fractures, but also can act as a preventative to decrease future fractures. Physical therapy programs that promote exercise targeting impairments in intrinsic back strength have been shown to improve the function and quality of life in those with osteoporotic vertebral fracture.[13] [36] [39]Several suggested exercises can be seen below.

- Focus on transverse abdominal control, properly learn to activate the TA, reverse curl ups, hip bridging

- Focus on strengthening transverse abdominals.

- Stabilization is increased through multifidus, transverse abdominal and oblique contraction. This exercise works both the core and back muscles, hitting the TA, multifidus and quadratus lumborum.

Thoracolumbar fracture therapy evidence closely parallels that of the lumbar spine and other exercises can be seen here Thoracic_Spine_Fracture.

Assuming the availability of necessary nutrients, stimulus to the osteoblasts results in a net gain in bone mass. Exercise is a form of repetitive loading that facilitates osteoblastic activity, thereby helping to maintain a positive balance between bone formation and bone resorption.[40]

Even the very moderate amount of exercise that is recommended for general wellness (a minimum of 30 minutes on most days) is helpful in preventing osteoporosis and maintaining bone density.

Overall, physical therapy has been shown to have no clinical significant difference in outcomes when compared to surgery for appropriate spinal fracture patients. Not only does physical therapy help relieve pain and disability as well as surgery, but the overall cost to the patient is greatly reduced.[36]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spine fractures, whether from an acute injury or progressive in nature like osteoporosis, occur often enough to merit adequate research with regard to healing procedures. A great deal of inquiry has gone into spinal surgery options, while very little appears to exist for specific physical therapy management. Most of the present information acknowledges that physical therapy, especially that of therapy and bracing can just as effectively manage lumbar fracture pain (without neurological involvement) as that of surgery. However, no current research exists that effectively compares the most effective therapy. Current recommendations revolve around basic core and lumbar spine strengthening as with most lumbar spine injuries. It is our recommendation that more research be done in this area that focuses specifically on lumbar spine fractures and the most effective therapy treatments for these injuries.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Holdsworth FW. Fractures, dislocations, and fracture-dislocations of the spine. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 1963 Feb;45(1):6-20.

- ↑ Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. spine. 1983 Nov 1;8(8):817-31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Aebi M. Classification of thoracolumbar fractures and dislocations. European spine journal. 2010 Mar;19(1):2-7.

- ↑ Andrew L Sherman et al. “Lumbar Compression Fracture” May 23, 2016

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOP). http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00368 (accessed 27 April 2011)

- ↑ Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, MichaelO'Fallon W, Melton III JL. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population‐based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985‐1989. Journal of bone and mineral research. 1992 Feb;7(2):221-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Heary RF, Kumar S. Decision-making in burst fractures of the thoracolumbar and lumbar spine. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2007 Oct;41(4):268.

- ↑ Davis JM, Beall DP, Lastine C, Sweet C, Wolff J, Wu D. Chance fracture of the upper thoracic spine. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2004 Nov;183(5):1475-8.

- ↑ Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(4):184-201. PubMed PMID: 7866834

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Finucane L, Downie A, Mercer CF, Greenhalgh S, Boissonnault WG, Pool-Goudzwaard A, et al. International Framework for Red flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1;50(7):350–72.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Weninger P, Schultz A, Hertz H. Conservative management of thoracolumbar and lumbar spine compression and burst fractures: functional and radiographic outcomes in 136 cases treated by closed reduction and casting. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2009 Feb;129(2):207-19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Lentle BC, Brown JP, Khan A, Leslie WD. Recognizing and Reporting Vertebral Fractures: Reducing the Risk of Future Osteoporotic. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 2007 Feb;58:1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Sherman AL, Razack N, Slipman CW et al. Lumbar Compression Fracture. Medscape Reference. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/309615-overview. Accessed April 25, 2011.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kim DH, Vaccaro AR. Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and considerations for treatment. The spine journal. 2006 Sep 1;6(5):479-87.

- ↑ Vaccaro AR, Lehman Jr RA, Hurlbert RJ, Anderson PA, Harris M, Hedlund R, Harrop J, Dvorak M, Wood K, Fehlings MG, Fisher C. A new classification of thoracolumbar injuries: the importance of injury morphology, the integrity of the posterior ligamentous complex, and neurologic status. Spine. 2005 Oct 15;30(20):2325-33.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Rihn JA, Anderson DT, Harris E, Lawrence J, Jonsson H, Wilsey J, Hurlbert RJ, Vaccaro AR. A review of the TLICS system: a novel, user-friendly thoracolumbar trauma classification system. Acta orthopaedica. 2008 Jan 1;79(4):461-6.

- ↑ Rampersaud YR, Fisher C, Wilsey J, Arnold P, Anand N, Bono CM, Dailey AT, Dvorak M, Fehlings MG, Harrop JS, Oner FC. Agreement between orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons regarding a new algorithm for the treatment of thoracolumbar injuries: a multicenter reliability study. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2006 Oct 1;19(7):477-82.

- ↑ Patel R, Appannagari A, Whang PG. Coccydynia. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Dec;1(3):223-6.

- ↑ Berry GE, Adams S, Harris MB, Boles CA, McKernan MG, Collinson F, Hoth JJ, Meredith JW, Chang MC, Miller PR. Are plain radiographs of the spine necessary during evaluation after blunt trauma? Accuracy of screening torso computed tomography in thoracic/lumbar spine fracture diagnosis. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2005 Dec 1;59(6):1410-3.

- ↑ Brown CV, Antevil JL, Sise MJ, Sack DI. Spiral computed tomography for the diagnosis of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine fractures: its time has come. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2005 May 1;58(5):890-6.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ang EC, Robertson AF, Malara FA, O’Shea T, Roebert JK, Schneider ME, Rotstein AH. Diagnostic accuracy of 3-T magnetic resonance imaging with 3D T1 VIBE versus computer tomography in pars stress fracture of the lumbar spine. Skeletal radiology. 2016 Nov;45(11):1533-40.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lenchik L, Rogers LF, Delmas PD, Genant HK. Diagnosis of osteoporotic vertebral fractures: importance of recognition and description by radiologists. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2004 Oct;183(4):949-58.

- ↑ http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00368

- ↑ Krompinger WJ, Fredrickson BE, Mino DE, Yuan HA. Conservative treatment of fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1986 Jan 1;17(1):161-70.

- ↑ Yi L, Jingping B, Gele J, Wu T, Baoleri X. Operative versus non‐operative treatment for thoracolumbar burst fractures without neurological deficit. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006(4).

- ↑ Sherman AL, Razack N, Slipman CW et al. Lumbar Compression Fracture. Medscape Reference. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/309615-overview. Accessed April 25, 2011

- ↑ Cengiz ŞL, Kalkan E, Bayir A, Ilik K, Basefer A. Timing of thoracolomber spine stabilization in trauma patients; impact on neurological outcome and clinical course. A real prospective (rct) randomized controlled study. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2008 Sep;128(9):959-66.

- ↑ Selznick LA, Shamji MF, Isaacs RE. Minimally invasive interbody fusion for revision lumbar surgery: technical feasibility and safety. Clinical Spine Surgery. 2009 May 1;22(3):207-13.

- ↑ Benzel EC, Ball PA. Management of low lumbar fractures by dorsal decompression, fusion, and lumbosacral laminar distraction fixation. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2000 Apr 1;92(2):142-8.

- ↑ Xiong J, Dang Y, Jiang BG, Fu ZG, Zhang DY. Treatment of osteoporotic compression fracture of thoracic/lumbar vertebrae by kyphoplasty with SKY bone expander system. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2010 Oct 1;13(05):270-4.

- ↑ Zhou JL, Liu SQ, Ming JH, Peng H, Qiu B. Comparison of therapeutic effect between percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty on vertebral compression fracture. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2008 Feb 1;11(01):42-4.

- ↑ Wardlaw D, Cummings SR, Van Meirhaeghe J, Bastian L, Tillman JB, Ranstam J, Eastell R, Shabe P, Talmadge K, Boonen S. Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2009 Mar 21;373(9668):1016-24.

- ↑ Stadhouder A, Buskens E, Vergroesen DA, Fidler MW, de Nies F, Öner FC. Nonoperative treatment of thoracic and lumbar spine fractures: a prospective randomized study of different treatment options. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2009 Sep 1;23(8):588-94.

- ↑ Wood K, Buttermann G, Mehbod A, Garvey T, Jhanjee R, Sechriest V. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of a thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit: a prospective, randomized study. JBJS. 2003 May 1;85(5):773-81.

- ↑ Shen WJ, Liu TJ, Shen YS. Nonoperative treatment versus posterior fixation for thoracolumbar junction burst fractures without neurologic deficit. Spine. 2001 May 1;26(9):1038-45.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Stadhouder A, Buskens E, de Klerk LW, Verhaar JA, Dhert WA, Verbout AJ, Vaccaro AR, Oner FC. Traumatic thoracic and lumbar spinal fractures: operative or nonoperative treatment: comparison of two treatment strategies by means of surgeon equipoise. Spine. 2008 Apr 20;33(9):1006-17.

- ↑ Wong CC, McGirt MJ. Vertebral compression fractures: a review of current management and multimodal therapy. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2013;6:205.

- ↑ Ohtori S, Yamashita M, Inoue G, Yamauchi K, Suzuki M, Orita S, Eguchi Y, Ochiai N, Kishida S, Takaso M, Takahashi K. L2 Spinal Nerve–Block Effects on Acute Low Back Pain From Osteoporotic Vertebral Fracture. The Journal of Pain. 2009 Aug 1;10(8):870-5.

- ↑ Bennell KL, Matthews B, Greig A, Briggs A, Kelly A, Sherburn M, Larsen J, Wark J. Effects of an exercise and manual therapy program on physical impairments, function and quality-of-life in people with osteoporotic vertebral fracture: a randomised, single-blind controlled pilot trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2010 Dec;11(1):1-1.

- ↑ Pirnay FM. Bone mineral content and physical activity. Int J Sports Med. 1987; 8:331-335