Malignant Melanoma

Original Editors - Emily Erwin & Brooke Sowards from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Emily Erwin, Brooke Sowards, Ellen Hosking, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, Calli Paydo and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A melanoma (see image R, nodular melanoma) is a tumor produced by the malignant transformation of melanocytes.

- Melanocytes are derived from the neural crest; consequently, melanomas, although they usually occur on the skin, can arise in other locations where neural crest cells migrate, such as the gastrointestinal tract and brain.

- Metastatic melanoma is known for its aggressive nature and for its ability to metastasise to a variety of atypical locations, which is why it demonstrates poor prognostic characteristics[1]

- The five-year relative survival rate for patients with stage 0 melanoma is 97%, compared with about 10% for those with stage IV disease[2].

The below 2 minute video shows the different type of skin cancers (including melanoma)

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes may be related to:

- Family history - Positive family history in 5% to 10% of patients; a 2.2-fold higher risk with at least one affected relative

- Personal characteristics - Blue eyes, fair and/or red hair, pale complexion; skin reaction to sunlight (easily sunburned); freckling; benign and/or dysplastic melanocytic nevi (number has better correlation than size); immunosuppressive states (transplantation patients, hematologic malignancies)

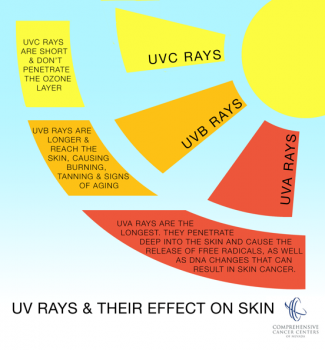

- Sun exposure over a lifetime - High UVB and UVA radiation exposure (Recent evidence has shown that the risk of melanoma is higher in people who use sunscreen. Because sunscreen mostly blocks UVB, people using sunscreen may be exposed to UVA more than the general public, provided those people are exposed to the sun more than the public at large); low latitude; number of blistering sunburns; use of tanning beds

- Atypical mole syndrome (formerly termed B-K mole syndrome, dysplastic nevus syndrome, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma) - Over ten years, 10.7% risk of melanoma (vs 0.62% of controls); higher risk of melanoma depending on number of family members affected (nearly 100% risk if two or more relatives have dysplastic nevi and melanoma)

- Socioeconomic status - Lower socioeconomic status may be linked to more advanced disease at the time of detection. One survey of newly-diagnosed patients found that low-SES individuals have decreased melanoma risk perception and knowledge of the disease.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of malignant melanoma is rapidly increasing worldwide, and this increase is occurring at a faster rate than that of any other cancer except lung cancer in women[2].

- Melanoma accounts for ~5% of all skin cancers, however, it remains the leading cause of death amongst skin cancers.

- The risk of metastatic progression has a strong association with the site of the initial primary melanoma, with melanomas arising from the head, neck and trunk carrying a higher risk of metastatic progression than those melanomas arising from the limbs[1]

- Melanoma is more common in Whites than in Blacks and Asians.

- Overall, melanoma is the fifth most common malignancy in men and the seventh most common malignancy in women, accounting for 5% and 4% of all new cancer cases, respectively.

- The average age at diagnosis is 57 years, and up to 75% of patients are younger than 70 years.

- Melanoma is notorious for affecting young and middle-aged people, unlike other solid tumors which mainly affect older adults. It is commonly found in patients younger than 55 years, and it accounts for the third highest number of lives lost across all cancers[2].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Melanomas

- May develop in or near a previously existing precursor lesion or in healthy-appearing skin.

- Solar irradiation induces many of these melanomas.

- May occur in unexposed areas of the skin, including the palms, soles, and perineum.

Certain lesions are considered to be precursor lesions of melanoma. These include the following nevi (moles):

- Common acquired nevus

- Dysplastic nevus

- Congenital nevus

- Cellular blue nevus

Melanomas have 2 growth phases,

- Radial malignant - Cells grow in a radial fashion in the epidermis

- Vertical - With time, most melanomas progress to the vertical growth phase, in which the malignant cells invade the dermis and develop the ability to metastasize.

Clinically, lesions are classified according to their depth, as follows:

- Thin - 1 mm or less

- Moderate - 1 mm to 4 mm

- Thick- greater than 4 mm

The 4 major types of melanoma, classified according to growth pattern, are as follows:

- Superficial spreading melanoma constitutes approximately 70% of melanomas; usually flat but may become irregular and elevated in later stages; the lesions average 2 cm in diameter, with variegated colors, as well as peripheral notches, indentations, or both

- Nodular melanoma accounts for approximately 15% to 30% of melanoma diagnoses; the tumors typically are blue-black but may lack pigment in some circumstances

- Lentigo maligna melanoma represents 4% to 10% of melanomas; the tumors are often larger than 3 cm, flat, and tan, with marked notching of the borders; they begin as small, freckle-like lesions

- Acral lentiginous melanoma constitutes 2% to 8% of melanomas in Whites and 35% to 60% of them in dark-skinned people; may appear on the palms and soles as flat, tan, or brown stains with irregular borders; subungual lesions can be brown or black, with ulcerations in later stages.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Most commonly, the history includes either changing characteristics in an existing mole or the identification of a new mole.

The characteristics of melanoma are commonly known by the acronym ABCDE and include the following:

- A - Asymmetry

- B - Irregular border

- C - Color variations, especially red, white, and blue tones in a brown or black lesion

- D - Diameter greater than 6 mm

- E - Elevated surface

Melanomas may itch, bleed, ulcerate, or develop satellites.

Patients who present with metastatic disease or with primary sites other than the skin have signs and symptoms related to the affected organ system(s).

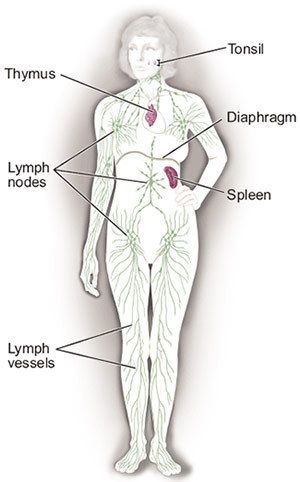

Important to examine all lymph node groups.[2]

Staging of Melanoma[edit | edit source]

Prognostic staging for malignant melanoma is accomplished using either the Breslow thickness or Clark level 1, 2.

Breslow thickness

- <0.76 mm: 5-year survival rate: 95% to 100%

- 0.76-1.5 mm: 5-year survival rate: 80% to 96%

- 1.5-4 mm: 5-year survival rate: 60% to 75%

- >4 mm: 5-year survival rate: 37% to 50%

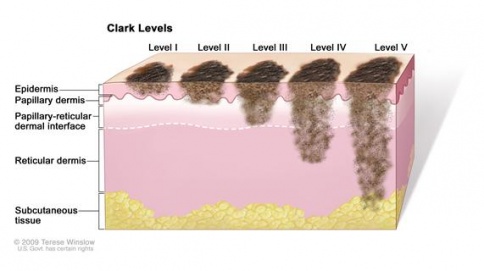

Clark level

- level I: tumour cells are maintained above the basement membrane

- level II: tumour cells have infiltrated the papillary dermis

- level III: tumour cells extend between papillary and reticular dermis, but do not invade the reticular dermis

- level IV: tumour cells have infiltrated the reticular dermis

- level V: tumour cells extend into subcutaneous tissue[1]

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Perform excisional biopsy on suggestive lesions so that a pathologist can confirm the diagnosis.

- Shave biopsies and electrodesiccation are inadequate; a full thickness of the skin is essential for proper histologic diagnosis and classification.

- The most important prognostic indicator for stage I and II tumors is thickness

- Biopsy results ultimately determine the margins of resection and which patients are candidates for sentinel lymph node biopsy and other adjuvant treatment.

Various laboratory studies eg Complete blood count; Complete chemistry panel (including alkaline phosphatase, hepatic transaminases, total protein, and albumin)

The following imaging modalities may also be ordered

- Chest radiography

- MRI of the brain

- Ultrasonography (possibly the best imaging study for diagnosing lymph node involvement)

- CT of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis

- Positron emission tomography (PET; PET-CT may be the best imaging study for identifying other sites of metastasis)

- Malignant melanoma can be diagnosed through various tests, such as biopsy and diagnostic imaging.

Terminolgy - Skin Biopsy

- Shave (tangential) biopsy: The top layer of the skin is shaved off with a small surgical blade. Useful when the risk of melanoma is very low. Generally not used if melanoma is strongly suspected because the sample may not be thick enough to measure how deeply the cancer has invaded the skin.[3]

- Punch biopsy: A punch biopsy removes a deep sample of skin, including the dermis, epidermis, and subcutaneous tissues.[3]

- Incisional biopsy: An incisional biopsy removes a portion of a tumor that has invaded the deeper layers of the skin.[3]

- Excisional biopsy: An excisional biopsy removes an entire cancerous tumor that has invaded the deeper layers of the skin. It is the desired method of biopsy for potential melanomas.[3]

- “Optical” biopsy: New methods have been developed that don’t require removal of a skin sample. An example is Reflectance Confocal Microscopy (RCM).[3]

- Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) biopsy: An FNA biopsy is used to biopsy enlarged, neighboring lymph nodes when a metastasis is suspected.[3]

- Surgical (excisional) Lymph Node biopsy: A surgical lymph node biopsy is used to remove an entire enlarged lymph node when a metastasis is suspected.[3]

- Sentinel Lymph Node biopsy: A sentinel lymph node biopsy is used to determine lymph nodes that may be the first affected areas if the melanoma metastasizes. This is often performed after melanoma has been diagnosed and the cancer exhibits certain characteristics, such as an abnormal thickness.[3]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

The most common sites of distant metastases include the lungs, lymph nodes, brain, and surrounding visceral pleura.

- Lungs: The earliest symptoms of pulmonary metastases are often dyspnea or pleural pain. Patient may report and increase in symptoms with deep breathing or physical activity. Patients may also experience a cough with bloody or rust colored sputum. Pleural pain may not be experienced until tumor cells have expanded to reach the pain fibers in the parietal pleura. [4]

- Lymph nodes: With metastases to lymph tissue, patients may have enlarged palpable lymph nodes. They may also report other symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, or infection. [4]

- Brain: Up to two thirds of patients with metastatic malignant melanoma will have brain metastases and one third will have metastases to the meninges. Brain metastases can produce a wide variety of signs and symptoms depending on the size and location of the lesion. [5]However, some of the most common symptoms include headache, vomiting, personality change, and seizures. Brain tumors may also result in paraneoplastic syndrome. This syndrome can cause unusual symptoms that occur in areas far from the site of metastases. [4]

Treatment and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Treatment of metastatic melanoma is complex

- Depends entirely upon the extent and site of pathological disease involvement.

- Wide excision of the identified primary tumour is the initial treatment of choice.

- If regional node involvement is suspected then lymphadenectomy can be performed.

- A combination of regional/systemic chemotherapy with associated immunotherapy and/or radiation therapy can be employed depending upon the individual clinical context.

Metastatic melanoma has a poor prognosis due to its aggressive nature and survival rates depend upon the staging of the disease.

- Patients with a single regional lymph node involvement have a 5-year survival rate of 80%, which then decreases depending upon the number of regional nodes involved.

- Individuals with evidence of distal disease have a poor prognosis with 5-year survival estimates being 22% for distal nodal involvement and fall to 8% for patients with other identified visceral metastatic disease[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Skin cancers are frequently seen by Physiotherapists.

- While many skin lesions are benign, it is important always to consider melanoma- as it is potentially deadly if the diagnosis gets missed.

- If there is suspicion of melanoma, the patient should obtain a referral to the dermatologist/oncologist and pathologist for further workup, irrespective of which of the other healthcare providers first became suspicious[2].

Physical Therapists

- Can play an integral role in treating or managing side effects of melanoma treatments. This can include minimizing lymphedema, wound management, and pain control. Therapists may also work with these patients to address symptoms from conventional cancer treatments such as fatigue, muscle weakness, and atrophy. [6]

- Should also be aware of contraindications to aerobic exercise for chemotherapy patients. Therapists should monitor vital signs and RPE during exercise. Observation for signs of infection, thrombocytopenia, DVT, dehydration, and electrolyte balance is also recommended. [4]

| Platelet count | <50,000/mm3 |

| Hemoglobin | <10 g/dL |

| WBC count | <3,000/mm3 |

| Absolute granulocytes | <2,500/mm3 |

Physical therapists have the training and skills to effectively manage cancer related treatment effects. Evidence supports the efficacy of aerobic training and strengthening exercises for preventing and managing cancer related fatigue and deconditioning during and after cancer treatment.[7]

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Radiopedia Malignant melanoma Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/metastatic-melanoma?lang=gb (last accessed 3.9.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Heistein JB, Acharya U. Cancer, Malignant Melanoma. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Mar 12. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470409/ (last accessed 3.9.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Melanoma Skin Cancer. American Cancer Society. Available at http://www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-melanoma/index. Accessed March 17, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Goodman CC, Snyder TE. Screening for Cancer. In: Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists, Screening for Referral. W B Saunders Company; 2012: 487-543.

- ↑ Secondary CNS Melanomas. Medscape. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1158059-overview. Accessed on: April 4, 2017.

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. The Integumentary System. In: Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2009: 392-452.

- ↑ The role of physical therapy in cancer [Internet]. World Physical Therapy Day. World Confederation for Physical Therapy; 2011 [cited 2017Apr4]. Available from: http://www.wcpt.org/sites/wcpt.org/files/files/WPTDay11_Cancer_Fact_sheet_C6.pdf