Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Case Study

Abstract[edit | edit source]

The purpose of this case study is to illustrate important clinical findings in an active patient recently diagnosed with relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and suggest an evidence-based management plan to address the patient’s participation restriction. The patient presents with decreased upper extremity coordination, upper extremity weakness, fatigue, impaired balance, and dexterity dysfunction. These clinical characteristics have led to decreased participation in her hobbies as well as occupational productivity, having substantial impact on her physical and mental state. The interventions suggested included balance training, coordination and dexterity training, and self-management. Baseline measures of her functional capacity were taken during initial assessment using self-reported and clinician-reported outcome measures. The outcome measures used included UEFS, FSMC, MSIS-29, six-minute walk test, and the nine hole peg test, which were reassessed 8 weeks later.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurological condition characterized by inflammatory demyelination over multiple episodes and locations in the central nervous system[1]. The complex nature of MS, its variance among patients, unpredictability, and potential to create a heavy social and emotional burden on patients can make appropriate, effective management challenging for community physiotherapists[1]. The debilitating symptoms (fatigue, arm movement and/or vision problems, ambulatory impairment, etc[1]) can considerably impact patients’ ability to fulfill their occupational, familial, and community roles.

The purpose of the present fictional case is to illustrate the clinical presentation of MS and propose appropriate, evidence-based management interventions that effectively address participation restrictions of an active patient.

Case:[edit | edit source]

A 29 year-old graphic designer, Betty Jackson first noticed her symptoms in the summer of 2019 while she was biking along the lake with her husband. She was experiencing difficulty reading signage and clumsiness using her arms while steering her bike. Upon completing her route, she felt excessively fatigued. These symptoms persisted for a few days, eventually affecting her productivity at work, prompting a visit to her family physician. MRI findings revealed demyelination and plaques in the corpus callosum; the physician classified her event as a “clinically isolated syndrome” of MS[1]. Approximately 10 months later, Betty’s symptoms resurfaced: she experienced the same fatigue, vision disturbances and arm issues. A secondary MRI revealed more distal demyelination & plaques; prompting a diagnoses of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)[1]. The physician referred her to a private physiotherapy clinic in the community for motor control training and gait safety education.Betty's recent diagnosis has caused her considerable stress and she is fearful of losing her job, or becoming unable to support her children because of considerable fatigue and/or potential progression of gait impairment in the future.

Fatigue is of great importance to Betty’s participation as a worker and a parent. Regular exercise has been cited widely in the literature as beneficial for promoting restful sleep and reducing fatigue in individuals with MS[2][3]. Therefore, education on and implementation of regular safe exercise should play a central role in Betty’s treatment plan. As for addressing Betty’s gait concerns, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society’s recommendations for managing gait impairment provide pertinent information to inform gait education and potential management of further impairment. They recommend addressing multiple aspects of gait including vision, fatigue, foot wear, and balance impairment[1].

Interestingly, in a case study conducted on a woman with similar concerns and clinical presentation, a 3 month locomotor training program involving a combination of virtual-reality based and overground balance interventions, and body-weight-supported/treadmill training twice a week, improvements were observed both at post-intervention and 2-month follow-up in gait speed, endurance and balance[4].

A challenging aspect of this case is the significant occupational modification that would likely be necessary for the patient. Graphic design requires a high level of upper extremity motor function, and without considerable workplace modification, ergonomic intervention, or additional support from the employer, continuing to pursue this line of work may prove unrealistic. For this reason the involvement of an occupational therapist and/or social worker may be warranted.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Betty Jackson is a 29 year old woman living with her spouse and two children in an apartment in Sudbury, Ontario. Her primary condition is RRMS. She was referred to the physiotherapy clinic by her general physician to address her motor control impairment. The physician also suggested education regarding gait and mobility aids to address Betty’s concerns about potential falls and disability. Additionally, Betty hopes to mitigate her fatigue so she can get more done at work.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment:[edit | edit source]

Assessment Date: May 12, 2020

Demographics

- Name: Betty Jackson

- Age: 29

- Sex: Female

History (Hx) of Present Illness:[edit | edit source]

Medical diagnosis: Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis

- Diagnosed in April 2020 following MRI imaging ordered by her family physician

- 2 previous relapses (first relapse in June 2019, second relapse in March 2020) in the last year both of which presented with excessive fatigue, blurry vision, impaired upper extremity function

Rehabilitation History: Previously attended physiotherapy regarding rehabilitation of a sprained left ankle following a sports injury approximately 10 yrs ago, but has not been to physiotherapy regarding current condition previously

Past Medical History:[edit | edit source]

- No current concomitant conditions or relevant past conditions

- No previous major surgeries

Current symptoms or status:

- Primary Complaints: Patient reports following her last relapse-remission episode, she has experienced uncoordinated, difficult arm and hand movements especially with her right arm which is her dominant side. In addition, the patient complains of occasional experiences of unsteadiness when taking a step, greater than normal fatigue following a work day and/or ADLs, and feeling “clumsier than usual”. Patient also reported occasional difficulty focusing on tasks at work.

- Aggravating Factors: warm weather, stressful work life

- Easing Factors: cooler weather, rest

Social History:[edit | edit source]

- Lives in an apartment with husband and two children (aged 4 and 5). Apartment building has 4 steps to the front entrance, and elevators to the patient's unit floor. Apartment unit has no stairs within. Husband works as an arborist (part-time to full-time depending on season). Patient also mentioned that her husband is a life-time indoor smoker and has no intention of quitting.

Hobbies: Enjoys biking with her husband, and playing with her kids

Occupation: Graphic designer, full-time

Functional status/Activity – current and previous

- Previously high activity level with complete independence

- No prior fall history but experiences occasional instability during longer periods of walking

- Currently reports difficulty with completing previously tolerable biking routes, and playing with her children for prolonged periods. Occasionally needs assistance from husband with work around the house and errands.

Other information:[edit | edit source]

Medications: Rebif[5] (self-administered subcutaneously 3x per week)

Diagnostic Tests/Investigations: MRI Imaging identifying both active and inactive demyelination plaques within the corpus callosum and in the periventricular white matter

Hand dominance: Right-handed

Health Habits: non-smoker, 1-2 wine glasses per week, no recreational drug use

Patient’s goals and concerns:

- Maintain and prevent decline of as much upper extremity function and balance in walking as possible

- Manage fatigue symptoms as patient feels she no longer is able to participate in biking routes with her husband and friends

- Patient expressed serious concerns about future potential decreases in her own function and mobility and how it will affect her ability to work and take care of her children. This is especially a concern as her husband’s occupation is busiest during the summer when the temperature is higher, and the symptoms seem to be worse. Another area of concern for the patient is the recently noticed decline in her right arm and hand function which will greatly impact her occupation.

Self-reported Measures:[edit | edit source]

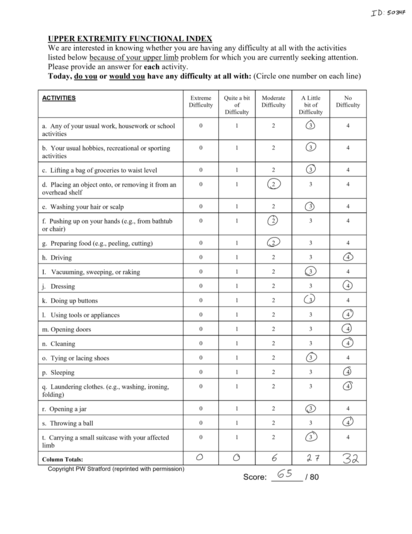

Upper Extremity Functional Index[6] (UEFI) was administered to assess the patient’s ability to complete everyday activities using her upper extremities. Patient scored 65/80 upon initial assessment. A lower score on the UEFI indicates higher levels of disability.

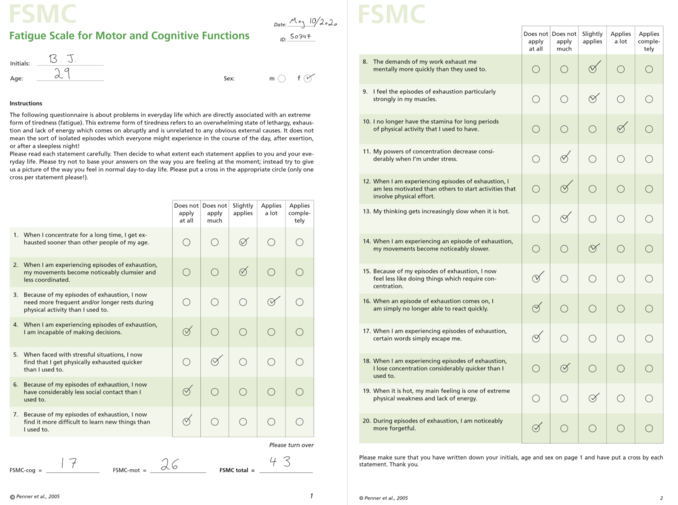

Fatigue Scale for Cognitive and Motor Function[7] was administered to assess the degree of the patient’s fatigue on cognitive and motor function. There is a high level of evidence and recommendation from the American Physical Therapy Association[8] Neurology Section Task Force regarding the use of this outcome measure in outpatient MS patients. Patient scored 43/100 on the total score indicating mild fatigue, 17/50 on the cognitive fatigue sub-score which is below the cut-off for identifiable fatigue, and 26/50 on the motor fatigue sub-score indicating mild motor fatigue ("The Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC): validation of a new instrument to assess multiple sclerosis-related fatigue" [9])

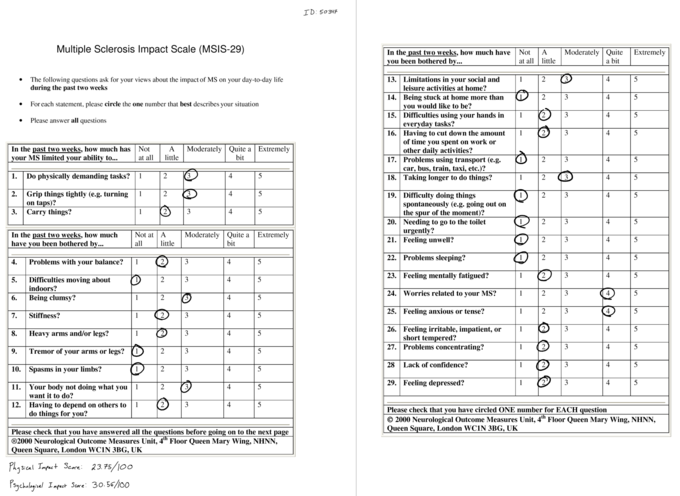

Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale[11] (MSIS-29) was used to assess the impact of MS on the patient’s physical and psychological day-today well being in the past 2 weeks. High levels of evidence and recommendation was given by the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force[8] regarding the use of this outcome measure in outpatient MS patients. The patient scored 23.75/100 in the physical impact scale and 30.56/100 in the psychological scale where higher scores indicate greater impact of MS on the patient’s daily well being. The MCID for the physical impact scale has been estimated to be 8 points, whereas the psychological impact scale MCID has yet to be agreed upon in in current literature[12].

Objective Assessment:[edit | edit source]

Observation: Patient is visibly anxious, shifting weight in the seat often, and speaking quickly especially during conversation about her work, taking care of her children and how the future impairments of MS will affect this. Patient walked into the clinic independently with no gait aid.

Posture: Slight forward head posture but otherwise unremarkable.

Cognition: Patient is oriented to person, place, and time as well as alert.

Myotomes: Within normal limits (WNL)

Dermatomes: WNL

Sensation Testing: WNL

Active ROM

- Csp: WNL

- Tsp: WNL

- Lsp: WNL

- L/E grossly: WNL

- U/E grossly: WNL

Manual muscle testing

- Left: L/E grossly 4-. U/E grossly 3+

- Right: L/E grossly 4-. U/E grossly 3+

LMN reflexes: Grossly grade 2+ (normal)

Clonus: Right side= Positive, Left Side=Negative [14]

Cranial Nerve Eye Movement Testing: Nystagmus noted intermittently in right eye [15]

Heel-to-toe Test: 10 repetitions each side

Left: WNL

Right: WNL

Finger-to-nose Test: 10 repetitions each side

- Patient was able to complete all repetitions bilaterally.

- Right: Patient’s movements become uncoordinated after 5th repetition and inaccurate upon target locating. Mild dysmetria noted as well.

- Left: Patient’s movements become uncoordinated after 8th repetition and inaccurate upon target locating. No dysmetria noted.

Finger-Opposition Test:

- Right: Slow, uncoordinated finger-to-pad movement noted.

- Left: slow movement noted during finger-to-pad noted. Coordination not affected.

Grip Strength-Dynamometer:

RS: 20kgs,

LS: 24kgs

- This is below average strength according to the age-based normative value[16].

6-minute walk test[17] (6MWT): 408m, slightly above mean for patients with MS with mild disability on EDSS[18].

- The 6MWT has high evidence and is recommended by the by the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force as an effective outcome measure to perform for patients with MS in outpatient clinical settings[8].

Gait: Step length and step cadence slowed as patient approached end of 6MWT. Right foot noted at initial contact. Poor right sided foot clearance due to foot drop during mid-swing as patient approached end of test.[14]

Spasticity: Modified Ashworth Scale[1].

- Lower extremity:

| Gross Body Movement | Modified Ashworth Grade - Left | Modified Ashworth Grade – Right |

| Hip Flexors | 0 | 0 |

| Hip Extensors | 0 | 0 |

| Hip Abductors | 0 | 0 |

| Hip Adductors | 0 | 0 |

| Knee Flexors | 0 | 0 |

| Knee Extensors | 0 | 1 |

| Ankle Dorsiflexors | 0 | 0 |

| Ankle Plantar Flexors | 0 | 1+ |

- Upper Extremity:

| Gross Body Movement | Modified Ashworth Grade - Left | Modified Ashworth Grade – Right |

| Shoulder Flexors | 0 | 1 |

| Shoulder Extensors | 0 | 0 |

| Shoulder Abductors | 0 | 1 |

| Elbow Flexors | 1 | 1 |

| Elbow Extensors | 0 | 0 |

| Wrist Flexors | 1 | 1+ |

| Wrist Extensors | 0 | 1 |

| Finger Flexors | 1 | 1+ |

| Finger Extensors | 1 | 1 |

(1): Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch and release or by minimal resistance at the end of the range of motion (ROM) when the affected part is moved in flexion or extension

(1+): Slight increase in muscle tone, manifested by a catch, followed by minimal resistance throughout the remainder (less than half) of the ROM [19].

- Left: 16 seconds

- Right: 19 seconds

- This is indicative of abnormal hand function in patients with MS who are at risk of limitations in activity and participation restrictions

- The American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force has rated this outcome measure with a high level of evidence for patients with MS in an outpatient setting[1].

50/56, Patient complained of feeling fatigued after item 11.

- This score is above the cut-off score of 45/56, therefore indicating there is currently no increased risk of falls for the patient [22].

The BERG balance scale is recommended and has a high quality of evidence for outpatient patients with MS as determined in a consensus report by the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force[8].

Clinical Impression:[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Diagnosis:

29yr old female diagnosed with remitting-relapsing multiple sclerosis presenting with decreased motor coordination in bilateral upper extremities especially on the right dominant side, weakness in bilateral upper extremity, fatigue, and altered gait mechanics. The symptoms and deficits experienced by the patient have caused decreased ability to independently participate in instrumental activities of daily living, decreased productivity at work, decreased balance, decreased conditioning due to fatigue, and overall anxious outlook regarding her future functioning and independence. Prognosis is positively affected by the patient’s high motivation to maintain functioning, supportive spouse, and previously high level of activity. Prognosis is negatively affected by anxious and stressful thoughts regarding future functions, and passive smoking at home which could affect cardiorespiratory outcomes. The patient will benefit from physiotherapy services to increase function of upper extremity, increased balance, manage fatigue, optimize gait pattern, and improve patient’s attitude towards the future.

Problem List:

- Bilateral upper extremity weakness

- Decreased upper extremity motor coordination affecting occupation and activities of daily living

- Increased right dominant hand dexterity affecting occupation

- Decreased tolerance to activity due to fatigue

- Decreased balance

- Altered gait pattern

- Decreased participation in hobbies

- Decreased productivity at work

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Gait Aid[edit | edit source]

The use of gait aids such as canes have been indicated as a fall risk factor in individuals with MS of varying ages [23][24][25]. Considering the patient's right-sided deficits during gait (i.e., step length/cadence, foot drop, poor foot clearance) particularly after several minutes of testing, an ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) or functional electrical stimulation (FES) can be worn to mitigate the drop foot.

Several studies have demonstrated that FES and AFO use can improve mobility, improve walking speed, reduce walking effort, and reduce incidence of falls, leading to improved quality of life in people with MS [26][27][28][29][30]. Bulley et al, 2014 concluded that individuals using either device (i.e., AFO or FES) reported assistance on hills/stairs, increased participation in life, greater confidence, less stress, and less mental effort when walking.[28]

Home Based Intervention[edit | edit source]

I). Aerobic Training: Taking into consideration the patient's hobbies, she can potentially seek out a bicycle with pedal assist (i.e., e-bike). An e-bike would allow her to pedal normally and if needed she can use the pedal assist (e.g., uphill or once fatigue begins to set in). Other methods of optimizing performance would be to have her bike at dusk or dawn to avoid the peak temperatures during the day and avoid overheating.

- Frequency: 2x/week

- Intensity: Moderate intensity (5/10 RPE)

- Type: Aerobic

- Time: 30min [31]

II). Dexterity and Upper Limb Training: The patient's occupation requires a certain degree of dexterity to manipulate different graphic design tools. The use of manipulable objects (e.g., clay, nuts/bolts, marbles) in patients with MS presenting with upper limb dexterity complications has been shown to significantly improve motor functioning, manual dexterity and hand grip strength [32][33][34].

II.a) Modeling Clay kneading: Patient kneads modelling clay with the hand forming a ball, flattening, and rolling and squeezing (5 sec) the clay (left and right hands).

- Frequency: 2x/week

- Intensity: Challenging without fatigue exacerbation

- Type: Dexterity

- Time: 15min

II.b) Assembly: Patient assembles bolts and nuts of varying sizes using both hands.

- Frequency: 2x/week

- Intensity: Challenging without fatigue exacerbation

- Type: Dexterity

- Time: 15min

II.c) Upper Limb Strengthening: Banded resistance training for shoulders and upper arms (Shoulder Flexion,Horizontal Abduction, Elbow Extension, Elbow Flexion).

- Frequency: 2x/week

- Intensity: 50% 1RM (light resistance band)

- Type: Muscular endurance

- Time: 1 set 10-15 reps with 1-2 minutes rest between exercises [31]

Therapist-Guided Interventions[edit | edit source]

I) Vestibular and Coordination Training (PT supervised): The patient expresses a fear of falling/tripping due to current balance deficits and is worried that her balance will continue to get worse. Specific balance and vestibular intervention have been shown to decrease risk of falls, decrease fatigue, and increase upright postural control[25][35].

Upright Postural Control: Standing with eyes open. Progress to foam surface and try with eyes closed when appropriate.

- BOS: firm surface—shoulder width apart

- BOS: firm surface—heels and toes together

- BOS: firm surface—tandem

Perform 1–3 with:

- Ball catch/toss (from and to PT)

- Head movement: head up (neck extension) and down (neck flexion)

- Frequency: 2x/week

- Intensity: Challenging without fatigue exacerbation

- Type: Vestibular/Coordination

- Time: 30min

II.) MS Education: There is strong evidence for incorporating education about fatigue management and energy conservation especially in conjunction to exercise programs. [35][36][37][38]

Education can include topics such as;

- Work simplification (finding ergonomic tools for her workplace)

- Impact of heat and time of day on fatigue level

- Mindfulness-based training

- The importance of continuing exercise after the treatment program for long-term benefits [39]

Outcome[edit | edit source]

After 8 weeks of biweekly sessions, the patient has increased finger dexterity demonstrated by a decrease of 4.6 seconds on the right and 7.1 seconds on the left during the Nine-Hole peg Test. The patient was able to purchase a used e-bike which she describes as life-changing. She is able to get on her bike and exercise without the fear of potentially getting stranded somewhere due to fatigue. The patient was able to receive funding through the Assistive Devices Program (ADP) allowing her to be fitted for an Ankle Foot Orthoses. As a result, decreased right foot drop and increased gait speed was observed. The results of the Six-Minute Walk Test also indicate a significant improvement of 79 meters from baseline (total 487 meters). Furthermore, the patient reports feeling more confident during ambulation. The patient demonstrated some other improvements according to the outcome measures re-administered during the last assessment. For the Upper Extremity Functional Scale (UEFS) she scored a 70/80 indicating improvement in upper extremity function. For the Fatigue Scale for Cognitive and Motor Function her total score of 36/100, (14/50 on cognitive fatigue and 22/50 on the motor fatigue) also indicates improvement. The MSIS-29 showed similar improvement, with a reduction of the physical impact score from 23.75 to 16.25, and the psychological impact score reduced to 25, from 30.56 prior. The patient has met all goals (i.e., increase balance, decrease fatigue, increase upper limb function and dexterity) and is ready to be discharged and seen on an “as needed” basis for exercise progression. The importance of continuing to be physically active and monitoring fatigue was emphasized to the patient during the last appointment.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

This case study investigates the clinical presentation of Betty, a young, active female patient diagnosed with RRMS. Betty initially presented to her family physician on two occasions about 10 months apart with symptoms of fatigue, impaired upper extremity function, and vision impairment. Subsequent to acquisition of MRI findings of demyelination plaques, Betty was diagnosed with RRMS by her physician and referred to physiotherapy for functional rehabilitation and management. Upon subjective and objective examination, the physiotherapist team was able to work with Betty to create a problem list, including impaired dexterity, coordination, balance, and fatigue, affecting her activity, participation, and occupation. Addressing occupation-related dysfunction using a biopsychosocial approach is paramount, as patients with MS may often experience negative outcomes and mental debilitation due to the complex nature of the disease[40]. For Betty, this included a comprehensive treatment plan including coordination, postural/balance, dexterity, aerobic, and gait aid training, which were monitored by various self-reported and clinician-reported outcome measures. Furthermore, implementation of self-management interventions such as education and activity modification (i.e., e-bike) is important due to the progressive nature of MS.

The broader implications of this case suggest the benefit of a multi-modal approach to both assessment and treatment for patients with mild RRMS. A comprehensive subjective and objective assessment to fully understand a patient's history, functional capabilities, and goals, are imperative in developing an appropriate treatment plan[41]. Utilization of outcome measures, applying a biopsychosocial model to treatment, and educating patients to self-monitor can reduce the negative impact that MS has on both physical and mental function[42]. However, due to the progressive nature of the disease, rehabilitation in severe cases becomes increasingly more complex [41]. Literature for more severe presentation of the disease is lacking, and thus future studies should aim to research the implications of severe MS.

Self study questions[edit | edit source]

Follow the hyperlinks to check your answer

In regard to multiple sclerosis, specific balance and vestibular intervention has evidence showing that it can:

a.) Decrease fatigue

b.) Increase anticipatory posture control

c.) Decrease fear of falling

d.) All of the above

Choose the CORRECT statement - Multiple sclerosis is a neurological condition characterized by inflammation and demyelination:

a.) With excessive fatigue lasting several years

b.) With unpredictability in all aspects of the disease

c.) Across time and locations within the CNS

d.) That has little effect on a patients day to day life

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Professional Resource Center. Multiple Sclerosis: A focus on rehabilitation. Available from: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Book-MS-A-Focus-on-Rehabilitation.pdf (Accessed 21/05/2020).

- ↑ Andreasen AK, Stenager E, Dalgas U. The effect of exercise therapy on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2011 Sep;17(9):1041-54.

- ↑ Motl RW, Gosney JL. Effect of exercise training on quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2008 Jan;14(1):129-35.

- ↑ Fulk GD. Locomotor training and virtual reality-based balance training for an individual with multiple sclerosis: a case report. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2005 Mar 1;29(1):34-42.

- ↑ Rebif (interferon beta-1a) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://mssociety.ca/managing-ms/treatments/medications/disease-modifying-therapies-dmts/rebif

- ↑ Upper Extremity Functional Index [Internet].2020 [Cited May 20]. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Upper_Extremity_Functional_Index

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Upper Extremity Functional Test [Internet]. My Turning Point. [cited 2020 May20]. Available from: https://myturningpoint.org/files/UEFI_2010.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Potter K, Cohen ET, Allen DD, Bennett SE, Brandfass KG, Widener GL, Yorke AM. Outcome measures for individuals with multiple sclerosis: recommendations from the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force. Physical therapy. 2014 May 1;94(5):593-608.

- ↑ Penner IK, Raselli C, Stöcklin M, Opwis K, Kappos L, Calabrese P. The Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC): validation of a new instrument to assess multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2009 Dec;15(12):1509-17

- ↑ Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions [Internet]. Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. 2014 [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/fatigue-scale-motor-and-cognitive-functions

- ↑ Hobart J. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): A new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(5):962–73.

- ↑ Motl RW, Putzki N, Pilutti LA, Cadavid D. Longitudinal Changes in Self-Reported Walking Ability in Multiple Sclerosis. Plos One. 2015;10(5).

- ↑ Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) [Internet]. Multiple Sclerosis Trust. [cited 2020May20]. Available from https://www.mstrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/MSIS-29.pdf

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Multiple Sclerosis: History and Exam [Internet]. BMJ Best Practice. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/140/history-exam

- ↑ Multiple Sclerosis: Approach [Internet]. BMJ Best Practice. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/140/diagnosis-approach

- ↑ Massy-Westropp NM, Gill TK, Taylor AW, Bohannon RW, Hill CL. Hand Grip Strength: age and gender stratified normative data in a population-based study. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4(1).

- ↑ Six Minute Walk Test / 6 Minute Walk Test [Internet]. Physiopedia. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Six_Minute_Walk_Test_/_6_Minute_Walk_Test.

- ↑ Wetzel JL, Fry DK, Pfalzer LA. Six-Minute Walk Test for Persons with Mild or Moderate Disability from Multiple Sclerosis: Performance and Explanatory Factors. Physiotherapy Canada. 2011;63(2):166–80.

- ↑ In Depth Review of the Modified Ashworth Scale [Internet]. Stroke Engine. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://www.strokengine.ca/en/indepth/mashs_indepth/

- ↑ Nine-Hole Peg Test [Internet]. Physiopedia. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Nine-Hole_Peg_Test

- ↑ Berg Balance Scale [Internet]. Physiopedia. [cited 2020May20]. Available from: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Berg_Balance_Scale

- ↑ Thorbahn LDB, Newton RA. Use of the Berg Balance Test to Predict Falls in Elderly Persons. Physical Therapy. 1996;76(6):576–83.

- ↑ Cattaneo D, Nuzzo CD, Fascia T, Macalli M, Pisoni I, Cardini R. Risks of falls in subjects with multiple sclerosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;83(6):864–7.

- ↑ Nilsagård Y, Lundholm C, Denison E, Gunnarsson L-G. Predicting accidental falls in people with multiple sclerosis — a longitudinal study. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009;23(3):259–69.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Coote S, Hogan N, Franklin S. Falls in People With Multiple Sclerosis Who Use a Walking Aid: Prevalence, Factors, and Effect of Strength and Balance Interventions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;94(4):616–21.

- ↑ Taylor PN, Hart IAW, Khan MS, Slade-Sharman DE. Correction of Footdrop Due to Multiple Sclerosis Using the STIMuSTEP Implanted Dropped Foot Stimulator. International Journal of MS Care. 2016;18(5):239–47.

- ↑ Dapul GP, Bethoux F. Functional Electrical Stimulation for Foot Drop in Multiple Sclerosis. US Neurology. 2015;11(01):10.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Bulley C, Mercer TH, Hooper JE, Cowan P, Scott S, Linden MLVD. Experiences of functional electrical stimulation (FES) and ankle foot orthoses (AFOs) for foot-drop in people with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2014;10(6):458–67.

- ↑ Linden MLVD, Hooper JE, Cowan P, Weller BB, Mercer TH. Habitual Functional Electrical Stimulation Therapy Improves Gait Kinematics and Walking Performance, but Not Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes, of People with Multiple Sclerosis who Present with Foot-Drop. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8).

- ↑ Esnouf J, Taylor P, Mann G, Barrett C. Impact on activities of daily living using a functional electrical stimulation device to improve dropped foot in people with multiple sclerosis, measured by the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;16(9):1141–7.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Guidelines: Physical Activity Guidelines for Special Populations: Multiple Sclerosis. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.csep.ca/en/guidelines/physical-activity-guidelines-for-special-populations.

- ↑ Ortiz-Rubio A, Cabrera-Martos I, Rodríguez-Torres J, Fajardo-Contreras W, Díaz-Pelegrina A, Valenza MC. Effects of a Home-Based Upper Limb Training Program in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016;97(12):2027–33.

- ↑ Lamers I, Maris A, Severijns D, Dielkens W, Geurts S, Wijmeersch BV, et al. Upper Limb Rehabilitation in People With Multiple Sclerosis. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2016;30(8):773–93.

- ↑ Kamm CP, Mattle HP, Müri RM, Heldner MR, Blatter V, Bartlome S, et al. Home-based training to improve manual dexterity in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2015;21(12):1546–56.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Hebert JR, Corboy JR, Manago MM, Schenkman M. Effects of Vestibular Rehabilitation on Multiple Sclerosis–Related Fatigue and Upright Postural Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy. 2011;91(8):1166–83.

- ↑ Khan F, Amatya B. Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2017;98(2):353–67.

- ↑ Asano M, Finlayson ML. Meta-Analysis of Three Different Types of Fatigue Management Interventions for People with Multiple Sclerosis: Exercise, Education, and Medication. Multiple Sclerosis International. 2014;2014:1–12.

- ↑ Finlayson M, Preissner K, Cho C, Plow M. Randomized trial of a teleconference-delivered fatigue management program for people with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2011;17(9):1130–40.

- ↑ Recommendations: Multiple sclerosis in adults: management: Guidance. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186/chapter/1-Recommendations

- ↑ Vijayasingham L, Mairami FF. Employment of patients with multiple sclerosis: the influence of psychosocial-structural coping and context [Internet]. Degenerative neurological and neuromuscular disease. Dove Medical Press; 2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6053901/

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Burks JS, Bigley GK, Hill HH. Rehabilitation challenges in multiple sclerosis [Internet]. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. Medknow Publications; 2009. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2824958/

- ↑ Kubsik A, Klimkiewicz P, Klimkiewicz R, Janczewska K, Woldańska-Okońska M. Rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2017;26(4):709–15.

Any and all images follow copyright regulations outlined by Physiopedia [1]