Non-operative Treatment of PCL Injury

Original Editor - Mariam Hashem

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt and Jess Bell

Basic Structure and Function[edit | edit source]

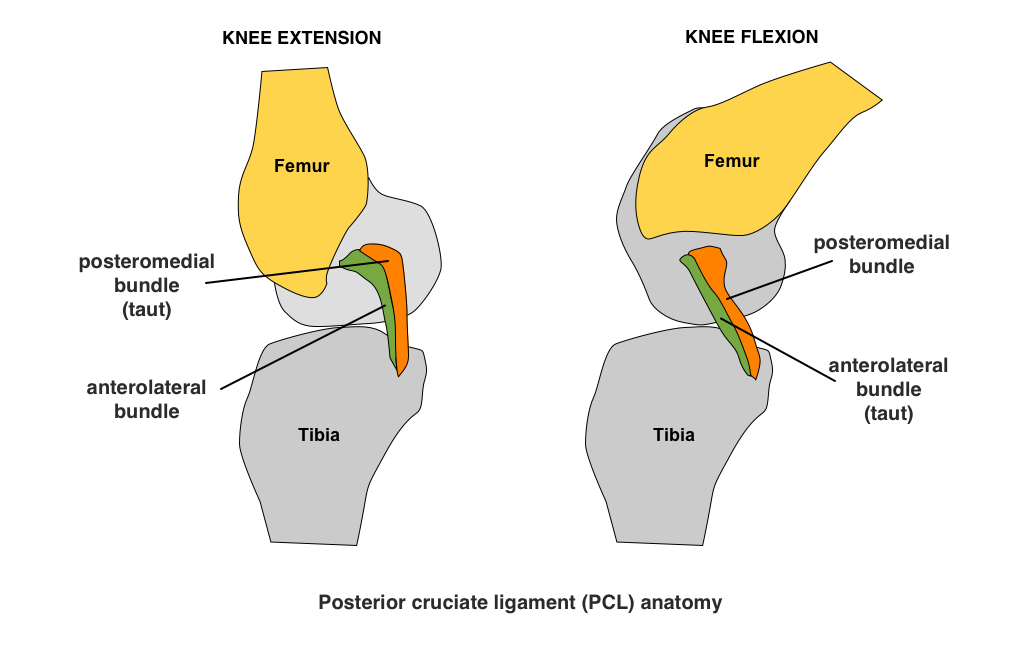

The PCL is a very large ligament, located posterior to the ACL, comprised of two bundles:[1]

- Anterolateral: tight when the knee is in flexion

- Posteromedial bundle: tight when the knee is in extension

Both bundles work synergistically to create stability within the knee.

Functions:

- PCL is the primary restraint to posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur[2]

- Secondary stabiliser resisting tibial external rotation as well as valgus/varus stresses[3]

The PCL is rarely injured in isolation.[4][5] They typically occur alongside other ligamentous, meniscal or chondral damage.[6] They are far less common than ACL or other knee ligament injuries.[4][7]

The mechanism of injury involves some type of varus or valgus force in combination with posterior tibial force.

Decision Making and Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Positive posterior drawer and posterior tibial sag signs are the most important tests to diagnose PCL and identify the management plan.[8]The posterior tibial sag sign is considered the most sensitive test for the integrity of the PCL.[9]

The decision regarding conservative or surgical management depends on the grade of injury and the associated soft tissue damage.

Grades:[10]

- Grade I: 0-5 mm posterior tibial translation

- Grade II: 5-10 mm posterior translation

- Grade III: > 10 mm posterior translation

Surgery is indicated for:

- All grade III combined PCL and posterior-lateral corner injuries. The combination of posterior laxity and rotational instability may lead to suboptimal outcomes as the joint fails to regain stability essential for active work-life or return to sport when returning to sports.

- Grade II and III isolated PCL failed conservative treatment reporting repeated instability and/or tibial shifting with activities

- Multi-ligamentous injury

Isolated PCL injuries, regardless of the grade, can be considered for conservative treatment.

Conservative Management Outcomes[edit | edit source]

When considering non-operatetive management for PCL, it is important to discuss short and long term goals with the patient for optimal decision making.

One study looked at 46 patients with MRI confirmed grade II and III PCL injuries managed conservatively from the time of injury until they returned to sports and reviewed them again at 5 years after the injury. The study reported an average of 16 weeks from the time of the injury until the return to competitive sports. 91% of those who returned to sports were able to play at the same level or higher at 2 years, and 69% played at the same level at the five-year follow-up. This indicates good outcomes of non-operative management in terms of returning to high levels of play and function.[13]

Despite the successful return to sports, the development of osteoarthritis is evident following non-operative PCL management.

A study that investigated 14 patients with PCL injuries found an increased anterior medial location of peak cartilage deformation reflecting higher than normal loads placed on the medial knee compartment. Another study in 2003 of 181 patients with PCL injuries treated conservatively after five years following injury, reported 77% degenerative changes in the medial femoral condyle and 47% had degenerative changes in the trochlea[14][15].

Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

The rehabilitation principals are no different from those following operative management.

Basically, to allow the ligament to heal in a neutral position, there are few essential precautions/restrictions[16] :

- Limit the force of gravity to create a more posterior tibial sagging, by encouraging your patient in the first 6 weeks to avoid positions where there is a tibia sag, such as wall slides. You can also advise sleeping with a pillow underneath the proximal tibia allowing the tibia to be in a better position and reducing the posterior drawing force.

- A dynamic PCL brace is considered one of the huge advances in PCL management. It works as a spring applying constant force drawing the tibia anteriorly and reducing tibial sag. Ideally, the PCL brace should be worn for 24 hours (except when taking a shower) for 16 weeks. A study in 2010[17] analyzed the effect of PCL dynamic brace on 21 patients for one year, found a reduction by 2.3mm of posterior tibial drawing at 12 months. This reflects the intrinsic healing capacity of the PCL and the effect of the PCL brace on reducing the grade of the injury. If the patient is unable to afford the cost of the brace, a knee immobilizer for the acute phases can be an alternative. Followed by a hinge athletic brace with a PCL strap for 12 months or longer depending on the knee stability.

- When working on improving the ROM, prescribe exercises from a prone position to limit the effect of gravity.

- Limit WB initially to restore joint homeostasis if the injury is accompanied by effusion and joint bleeding.

- Limit isolated hamstrings contraction at greater than 15 degrees knee flexion for at least 16 weeks as it was found to increase the load on PCL[18]. Instead, you can advise an exercise such as Romanian deadlift where there is a small knee flexion to avoid excessive tibial forces.

Acute Rehabilitation:[edit | edit source]

Aims:

- Restore ROM

- Reduce swelling

- Manage the inflammatory process

- Restore muscle function

ROM: (0-4 weeks)[16]

1- Assisted prone ROM exercises

2- Progress to a stationary bike when 115 degrees knee flexion is achieved or when the ROM allows for a revolution on the bike.

Swelling management:

- Ice

- Elevation

- Load management by limiting weight-bearing to allow healing.

Muscle function: teaching quadriceps activation is vital as quadriceps muscle draws the tibia anteriorly, improving stability. Encourage isolated quadriceps contraction by drawing the patella superiorly.

Progression to weight-bearing exercises when the patient meets the following:

- 130 degrees knee flexion

- Terminally knee extension

- Able to walk comfortably for a distance in the brace

Late Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

- Muscle endurance (weeks 5-10): low load and high repetitions. e.g; 15 repetitions, 3-4 sets with 40 seconds rest. Example of exercises:

- Walking forward and backwards with Theraband

- Bilateral squat

- Progress to eccentric exercises such as stepping down from a 1'' box

- Single leg Romanian deadlift or deadlift

- Muscle strength (weeks 11-16): low repetition and high load. e.g; 10-12 repetitions, 3 sets with 1-minute rest. You can adapt the same exercises used for endurance training and adjust the parameters or advice higher load exercises such as elevated splint squat. Additionally, Lumbo-pelvic rhythm exercises are important to improve stability

- Power, agility and running (weeks 17-20/22)[16]

Return to Sports[edit | edit source]

Completing a proper strength programme is recommended prior to return to sports.

Criteria for progression or return to play:

There are available criteria in the evidence, however, symmetry on the following measures reflects strength and stability[16]:

- Quadriceps strength

- Y balance anterior reach distance

- Power test such as hop test

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Logterman SL, Wydra FB, Frank RM. Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Anatomy and Biomechanics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(3):510-4.

- ↑ Lynch TB, Chahla J, Nuelle CW. Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament. J Knee Surg. 2021 Apr;34(5):499-508.

- ↑ Seon, J. Anatomy and function of the posterior cruciate ligament . In: Kim, JG, editor. Knee Arthroscopy. Springer, Singapore, 2021. p149-52.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vaquero-Picado A, Rodríguez-Merchán EC. Isolated posterior cruciate ligament tears: an update of management. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2(4):89-96.

- ↑ Ng JWG, Ali FM. Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Journal of Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery. 2021;8(4):319-25.

- ↑ Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy M, et al. Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Current Concepts Review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6(1):8-18.

- ↑ Marom N, Ruzbarsky JJ, Boyle C, Marx RG. Complications in Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries and Related Surgery. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2020;28(1):30-3.

- ↑ Lee BK, Nam SW. Rupture of Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Diagnosis and Treatment Principles. Knee Surgery and Related Research 2011 Sep;23(3):135-141.

- ↑ Lamb S, Koch S, Nye NS. Posterior cruciate ligament injury. In: Coleman N., editor. Common pediatric knee injuries. Springer, Cham, 2021. p133-41.

- ↑ Malone AA, Dowd GSE, Saifuddin A. Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee. Injury 2006;37(6):485-501.

- ↑ Posterior Drawer test for PCL. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HTti7-c1MFk

- ↑ Posterior Sag Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kB__q4Y4lfA

- ↑ Agolley D, Gabr A, Benjamin-Laing H, Haddad FS. Successful return to sports in athletes following non-operative management of acute isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries: medium-term follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(6):774–778. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B6.37953

- ↑ Strobel MJ, Weiler A, Schulz MS, Russe K, Eichhorn HJ. Arthroscopic evaluation of articular cartilage lesions in posterior cruciate ligament—deficient knees. Arthroscopy: the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery. 2003 Mar 1;19(3):262-8.

- ↑ Van de Velde SK, Bingham JT, Gill TJ, Li G. Analysis of tibiofemoral cartilage deformation in the posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume.. 2009 Jan 1;91(1):167.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 O'Brien, L. Non-operative Treatment of PCL Injury Course, Plus2019

- ↑ Jacobi M, Reischl N, Wahl P, Gautier E, Jakob RP. Acute isolated injury of the posterior cruciate ligament treated by a dynamic anterior drawer brace: a preliminary report. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2010 Oct;92(10):1381-4.

- ↑ Markolf KL, O'Neill G, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. Effects of applied quadriceps and hamstrings muscle loads on forces in the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. The American journal of sports medicine. 2004 Jul;32(5):1144-9.

- ↑ medi USA. M.4s® PCL dynamic – The new standard for PCL therapy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKiCTVgSvK4

- ↑ Y Balance Test Explained . Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gfGkxWlx4o

- ↑ Physio REHAB. ACL + Knee Injury - Return to Sport Tests (Pt.1) | Tim Keeley | Physio REHAB. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0xp8-2nLhs [last accessed 25/06/2024]