Pusher Syndrome

Original Editor - Lizzie Cotton

Top Contributors - Kate Sampson, Sehriban Ozmen, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Kim Jackson, Lizzie Cotton, Admin, Claire Knott, Dinu Dixon, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Oyemi Sillo, Naomi O'Reilly and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

First described by Patricia Davies in 1985, [1] "Pusher Syndrome" is a term used to describe the behaviour of individuals using their non-paretic limb to push themselves towards their paretic side. Left unsupported, these patients demonstrate a loss in lateral posture, falling onto their paretic side. [2]

Pusher Syndrome (also has been referred to as contraversive pushing or ipsilateral pushing) is a motor behavior characterized by active pushing with the stronger extremities towards the hemiparetic side with a lateral postural imbalance,[3] generally seen after stroke [4] and is often accompanied by severe inattention and hemisensory impairments. [1][5] Incidence of this disorder after stroke is inconsistent in the literature; ranging from approximately 5-10% [6] [7] to 63% [8].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The tilted orientation of the body verticality in people with pusher syndrome was found to be associated with the lesion of the posterior thalamus. [9]

Thalamus is a structure of the diencephalon. It has different nuclei formed mainly by neurons of excitatory and inhibitory nature and each with a unique speciality. It is mostly composed of grey matter. The white matter parts are external medullary laminae covering the lateral surface of the thalamus and internal medullary laminae dividing the nuclei into three (anterior, medial and lateral) groups. [10]

The posterior thalamus plays a fundamental role in the control of upright body posture. [9] Some nuclei in this part of the thalamus are sensitive to vestibular stimulation. [11][12]

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Despite the increase in investigation in the causes and symptoms of Pusher Syndrome, it is still a poorly understood presentation. It has been suggested that Pusher behaviour may be a result of a conflict between an impaired somesthetic perception of vertical, and intact visual system or that it may be a consequence of a high-order disruption of somatosensory information processing from the paretic hemi-body.[13] Patients with Pusher Syndrome may also have primary visual or visual perceptual problems, impaired proprioception, and motor impairments, which leave them less able to relearn posture and balance. [14]

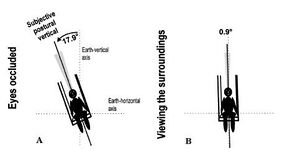

Karnath et al demonstrated that patients with Pusher Syndrome have a misperception of their upright body posture; with patient’s reporting an “upright” posture when actually tilted 18 degrees to the ipsilesional side. With MRI scanning, the patients included in this study typically demonstrate left or right posterolateral thalamus damage post stroke. [9] However the evidence around location of infarct is conflicting with some studies also suggesting damage to the parietal area. [2] [13]

Several previous studies suggested that pusher behavior was more observed in patients with right brain damage than in patients with left brain damage [15]. Abe et al also suggested that there could be increased prevalence of Pusher Syndrome with right sided hemisphere damage [16]. Paci et al in their review suggested that the range of evidence in Pusher Syndrome may be due to a multidimensional network responsible for upright postural control. [13]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Kim and Seok-Hyun [15] identified the following symptoms on patients with Pusher Syndrome:

- Flexed position of affected side limbs

- Extended position of the unaffected side limbs

- Severe damage to the balance ability ( loss of postural balance)

- Severe altered perception of the body's orientation in relation to gravity

- Resistance to any attempts to rectification

- Normal visual and vestibular system function

- Spatial neglect and anosognosia with right brain injury

- Spatial aphasia with left brain injury

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Karnath and Broetz [17] identify three diagnostic factors of Pusher Syndrome, as shown below:

- Spontaneous Body Posture (severe/moderate and mild)

The patient’s initial posture shown immediately after a positional change (ideally supine to sit/ sit to stand) must be assessed for contralateral tilting. This can be seen with or without falling to the side contralateral to the brain lesion. It is felt that patient’s must demonstrate this postural abnormality regularly to be classified as suffering with Pusher Syndrome. - Abduction and Extension of the Nonparetic Extremities

Patients demonstrate abnormal positioning of the side ipsilateral to the brain lesion. Typically the hand will be abducted away from the body, the elbow held in extension and the hand searching for contact with a surface on which to push oneself to the perceived upright position. The lower limb may be abducted, with the knee and hip held in extension (as with the upper limb). - Resistance to Passive Correction of Tilted Posture

Patients will typically actively resist against therapist’s manual interventions to correct their body posture. The patient’s extended upper and lower limbs will be used to push their weight towards their paretic side.

Subsequently, the Standardized Scale for Contraversive Pushing (SCP), has been formulated on these 3 deficits. The SCP is a useful tool for clinicians to classify Pusher Syndrome, and is quick and easy to apply in both an acute and rehabilitation setting [18].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Burke Lateropulsion Scale[edit | edit source]

- This scale assesses the patient’s resistance to:

- Passive supine rolling

- To passive postural correction when sitting and standing

- To assistance during transferring and walking.

- The score for each component s rated on a scale from 0 to 3 (0 to 4 for standing) and the score is based on the severity of resistance or the tilt angle when the patient begins to resist the passive movement. The score for diagnosis of Pusher behaviour is ≥2 points . [19]

Scale for Contraversive Pushing[edit | edit source]

- This is made up of 3 components

- The symmetry of spontaneous body posture (rated with 0, 0.25, 0.75, or 1 point)

- The use of non-paretic extremities (0, 0.5, or 1 point)

- The resistance to passive correction of the tilted posture (0 or 1 point).

- For a diagnosis of Pusher Syndrome all 3 components need to be present. [19]

Bergmann et al suggested that the Burke Lateropulsion Scale is more sensitive to small changes in presentation and is more responsive in classifying Pusher behaviour than the Scale for Contraversive Pushing. In addition it was suggested that the Burke Lateropulsion Scale is especially useful to detect mild or resolving pusher behaviour in standing and walking.[19]

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Karnath and Broetz [17] suggested that the first goal of initial rehabilitation is to provide visual feedback of the patient’s altered body posture. By providing patients with visual information in relation to their environment they are able to feel they are in an erect posture when they see that they are tilted. While in different postural sets patients should be asked whether they see if they are upright and given visual references/cues to help them orientate themselves to upright and given them feedback about their body orientation. For example by using ground-vertical structures- ie a therapist’s arm held upright to demonstrate true upright orientation, a line on a wall or a door frame. Although patients with Pusher Syndrome may initially need prompting with the use of visual feedback it is hoped that, with regular therapy, patients are able to apply training procedures independently and utilise their environment for gaining visual feedback from vertical structures [20].

Kim and Seok-Hyun suggested the stimulation of the trunk flexor with the appropriate lower muscle tone as well as maintaining the posture with the trunk moving in the direction of the given goal [15].

Karnath and Broetz suggested from their clinical experience that the following sequence of treatment may be effective in treatment of Pusher Syndrome:

- Enable the patient to visually explore their surroundings and the body's relationship to their environment and see whether he or she is oriented upright. Reference points can be used such as the therapist's arm or many vertical structures, such as door frames, windows or pillars.

- Practicing movements necessary to reach a vertical body position.

- Performing functional activities whilst maintaining a vertical body position [17].

More recent treatments suggest to: [15]

- Enable the patient to realize the disturbed perception of upright body position.

- Learn the movements that are necessary to reach a vertical body position.

Other recent treatment options that found to be useful are: interactive visual feedback training, mirror visual feedback training [21], lateral stepping with body weight–supported treadmill training [22] robot-assisted gait training [23], standing frame [24].

Abe et al suggested that when considering length of rehabilitation stay that laterality and prognosis of Pusher Syndrome should be considered at the time of goal setting for rehabilitation [16].

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

There are conflicting opinions in the literature with regards to the persistence of Pusher Syndrome in the longer term and its impact on functional outcome. Some authors report that the presence of Pusher Syndrome is rarely seen 6 months post stroke and is shown to have no negative impact upon patients’ ultimate functional outcome, although it has been shown to slow rehabilitation by up to 3 weeks [17]. However, a case study by Santos-Pontelli et al [2] reported the lingering presence of Pusher Syndrome in 3 patients up to two years post-stroke, with profound negative impacts upon their functional abilities.

In a study by Babyar et al they reviewed whether the number of impairments patients with Pusher Syndrome had, was a determinant on the level of recovery achieved [14] From their findings they proposed that 90.5% of patients studied with only a motor presentation were able to 'recover' (scoring 0 or 1 in the Burke Lateropulsion Scale) from Pusher Syndrome within 27 days. Those patients with with 2 deficits achieved the target in about 59% of cases.For patients with motor, proprioceptive, and visual–spatial impairments or hemianopia however, only 37% of patients were able to achieve a score of 0 or 1 on the Burke Lateropulsion Scale prior to discharge.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A clinical picture similar to pusher syndrome may occur in patients with hemiparesis because of the loss of balance. In this sense, the term contraversive pushing is distinctive as it emphasizes the pushing of the non-hemiparetic extremities towards the contralateral side of the brain lesion. In addition, the hemiparetic patient without pushing syndrome realizes that he/she has lost his balance and tries to hold onto something to support himself/herself with his non-paretic hand, so presents pulling rather than pushing. [17] But the patient with pushing syndrome resists any attempt to correct their tilted position. [26]

Resources[edit | edit source]

The "Pusher" syndrome, assessment and treatment: Part 1 [27]

The “Pusher “syndrome, assessment and treatment: Part 2 [28]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (Davies PM. Steps to Follow: A Guide to the Treatment of Adult Hemiplegia. New York, NY: Springer;1985)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Santos-Pontelli TEG, Pontes-Neto OM, de Araujo DB, Santos AC, and Leite JP. Persistent pusher behavior after a stroke. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011; 66(12): 2169–2171.

- ↑ Karnath H, Ferber S, and Dichgans J: The origin of contraversive pushing. Evidence for a second graviceptive system in humans. Neurology 55(9): 1298, 2000.

- ↑ Pardo V, Galen S. Treatment interventions for pusher syndrome: A case series. NeuroRehabilitation. 2019 Jan 1;44(1):131-40.

- ↑ Perennou DA, Amblard B, Laassel el M, et al. Understanding the pusher behavior of some stroke patients with spatial deficits: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:570-575.

- ↑ Pedersen PM, Wandel A, Jorgensen HS, et al. Ipsilateral pushing in stroke: incidence, relation to neuropsychological symptoms, and impact on rehabilitation—the Copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.1996 ;77:25–28

- ↑ Roller M. The ‘Pusher Syndrome. Journal of Neurological Physical Therapy. 2004; 28 (1): 29-34

- ↑ Danells CJ, Black SE, Gladstone DJ, McIlroy WE. Poststroke “pushing” Natural history and relationship to motor and functional recovery. Stroke. 2004 Dec 1;35(12):2873-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Karnath HO, Johannsen L, Broetz D, Küker W. Posterior thalamic hemorrhage induces “pusher syndrome”. Neurology. 2005 Mar 22;64(6):1014-9.

- ↑ Torrico TJ, Munakomi S. Neuroanatomy, Thalamus. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542184/

- ↑ Deecke L, Schwarz DW, Fredrickson JM. Nucleus ventroposterior inferior (VPI) as the vestibular thalamic relay in the rhesus monkey I. Field potential investigation. Experimental brain research. 1974 Apr;20:88-100.

- ↑ Buttner U, Henn V. Thalamic unit activity in the alert monkeys during natural vestibular stimulation. Brain research. 1976.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Paci M, Baccini M, Rinaldi LA. Pusher behaviour: a critical review of controversial issues. Disability and rehabilitation. 2009 Jan 1;31(4):249-58

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Babyar SR, Peterson MG, Bohannon R, Pérennou D, Reding M. Clinical examination tools for lateropulsion or pusher syndrome following stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:639-650.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Kim CS, Seok-Hyun Nam PT. Neurophysiological and Clinical Features of the Pusher Syndrome. Journal of Korean Physical Therapy. 2010 Jun 25;22(3):45-8.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Abe H, Kondo T, Oouchida Y, Suzukamo Y, Fujiwara S, Izumi SI. Prevalence and length of recovery of pusher syndrome based on cerebral hemispheric lesion side in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2012 Jun 1;43(6):1654-6

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Karnath HO and Broetz D. Understanding and Treating “Pusher Syndrome. Physical Therapy. 2003;83:12:1119-1125

- ↑ Karnath HO, Ferber S, Dichgans J. The Origin of Contraversive Pushing: Evidence for a Second Graviceptive System in Humans. Neurology. 2000;55:1298-1304

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bergmann J, Krewer C, Rieß K, Müller F, Koenig E, Jahn K. Inconsistent classification of pusher behaviour in stroke patients: A direct comparison of the Scale for Contraversive Pushing and the Burke Lateropulsion Scale. Clinical rehabilitation. 2014 Jan 23:0269215513517726.

- ↑ Karnath H-O, Ferber S, Dichgans J. The neural representation of postural control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2000 ;97:13931–13936.

- ↑ Yang YR, Chen YH, Chang HC, Chan RC, Wei SH, Wang RY. Effects of interactive visual feedback training on post-stroke pusher syndrome: a pilot randomized controlled study. Clinical rehabilitation. 2015 Oct;29(10):987-93.

- ↑ Romick-Sheldon D, Kimalat A. Novel treatment approach to contraversive pushing after acute stroke: A case report. Physiotherapy Canada. 2017;69(4):313-7.

- ↑ Bergmann J, Krewer C, Jahn K, Müller F. Robot-assisted gait training to reduce pusher behavior: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2018 Oct 2;91(14):e1319-27.

- ↑ Gillespie J, Callender L, Driver S. Usefulness of a standing frame to improve contraversive pushing in a patient post-stroke in inpatient rehabilitation. InBaylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2019 Jul 3 (Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 440-442). Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ ARC Seminars L.L.C. Pusher Syndrome: How to better facilitate midline orientation. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zfJBwuNAHc [Accessed, 17/09/2021]

- ↑ Karnath HO. Pusher syndrome–a frequent but little-known disturbance of body orientation perception. Journal of neurology. 2007 Apr;254:415-24.

- ↑ van de Rakt J, Mccarthy-Grunwald S. The" Pusher" syndrome, assessment and treatment: part 1. Italian Journal of Sports Rehabilitation and Posturology. 2021;8(18):1904-34.

- ↑ van de Rakt J, McCarthy-Grunwald S. The “Pusher “syndrome, assessment and treatment. Part 2. Ita. J. Sports Reh. Po. 2022;9(21):3.