Bone bruise: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (54 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class=" | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors - '''Laurien Henau as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project. | |||

''' | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} - . | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == What is a bone bruise? == | ||

A bone bruise is a type of bone injury. | |||

* Other examples of bone injuries include [[Stress Fractures|stress fractures]], osteochondral fractures and a variety of different patterns of bone [[Fracture|fractures]].<sub><ref name="p3" /></sub> | |||

* A bone bruise is characterised by three different kinds of bone injuries including: sub-periosteal hematoma, inter-osseous bruising and a sub-chondral lesion, or a combination of these. <sub><ref name="p6">V. Mandalia, J.H.L. Henson. Traumatic bone bruising – A review article, European Journal of Radiology 2008; 67; 54–61 Grades of recommendation A</ref></sub> | |||

* A bone bruise is differentiated from the alternative fracture types in that only some of the trabeculae are broken.<sub><ref name="p9">Janice Polandit, 5 Things You Need to Know About a Bone Bruise, 2011; http://www.livestrong.com/article/5521-need-bone-bruise/ Grades of recommendation F</ref></sub> | |||

== | == Clinically Relevant Physiology == | ||

Bone | Bone tissue is a specialised form of connective tissue that is made up of an organic matrix (collagen and glycosaminoglycans) and inorganic minerals (calcium and phosphate). <sub><ref name="p1">L.C. Jungueira and J. Carneiro, “Functional Histology” 2010; 167</ref></sub> An adult human skeleton contains 80% cortical bone and 20% trabecular bone. Both types of bone are composed of osteons. Cortical bone is the solid type of bone and trabecular bone resembles honeycomb which is comprised of a network of trabecular plates and rods. Read more about the histology and physiology of [[Bone|bone here]]. | ||

[[File:Bone_1.jpg|frameless|400x400px]][[File:Bone_2.jpg|frameless|520x520px]] | |||

The | == Epidemiology == | ||

The most common cause of bone bruise is trauma however the condition can also be associated with normal stress loading and haemophilia A and B.<sub><ref name="p52">Prof. Dr. S. Van Creveld and Dr. M. Kingma Subperiostal haemorrhage in haemophilia A and B. Ned. T. Geneesk. 105. I. 22. 1961; 1095-1098 Grades of recommendation F</ref></sub> | |||

The | The most commonly affected area is the lower limb. <sub><ref name="p7">Christoph Rangger, Anton Kathrein, Martin C Freund, et al. Bone Bruise of the Knee. Acta Orthop Scand 1998; 69(3) : 291-294. Grades of recommendation B</ref></sub> | ||

= | Patients with a bone bruise tend to have protracted clinical recovery, with more effusion and a slower return of motion. <sub><ref name="p3" /></sub> | ||

In patients with [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)|ACL rupture]] there is an 80% probability of concurrent associated bone bruising at the femoral condyle or tibial plateau.<sub><ref name="p3" /><ref name="p1" /></sub> According to Boks et al. 2007, the presence of bone bruising in these zones is the most important secondary sign in the diagnosis of ACL injury. | |||

[[File:Bone_3.jpg|frameless|392x392px]] | |||

MRI with white arrow indicating presence of bone bruising in the (a) post-lateral talus area and (b) the caudal tibia epiphysis.<br> | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

!Bone Injury Type | |||

!Characteristics | |||

!Typical Injury Mechanism | |||

|- | |||

|Sub-periosteal hematoma | |||

|A concentrated collection of blood underneath the periosteal of the bone. | |||

|Direct high-force trauma to the bone | |||

|- | |||

|Inter-osseous bruising | |||

|Damage of the bone marrow. The blood supply within the bone is damaged, and this causes internal bleeding. | |||

|Repetitive compressive force on the bone (extreme pressure on regular base). | |||

|- | |||

|Sub-chondral lesion | |||

|Lesion occurs beneath the cartilage layer of a joint. | |||

|Extreme compressive force or rotational mechanism such as testing (shearing force) that literally crushes the cells | |||

Force causes separation of the cartilage (or ligament) and the underlying bone, plus bleeding when the energy of the impact extends into the bone. | |||

|} | |||

<br>For the all bone injuries, incidence rates tend to be higher amongst professional athletes and those that run and jump frequently on hard surfaces, for example football and basketball players. <sub><ref name="p3" /><ref name="p6" /></sub> | |||

< | |||

== | |||

< | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

Although an x-ray should identify whether or not there is a bone fracture, a bone bruise is not able to be diagnosed using [[X-Rays|x-ray]] imaging. The current "gold standard" diagnostic imaging method for bone bruises is the [[MRI Scans|MRI]], in particular T2-weighted fat-suppressed images or T1-weighted imaging.<sub><ref name="p1" /></sub><br> | |||

[[File:Bone_7.jpg|center|frameless|395x395px]] | |||

[[File:Bone_6.jpg|center|581x581px]] | |||

<div></div> | |||

< | [[Image:Bone 5.jpg|569x569px|center]] | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Bone 9.jpg|left|1126x1126px]] | |||

<div><br></div> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | |||

[[Image:Bone 10.jpg|1129x1129px]] | |||

== | <ref name="p3" /><ref name="p6" /><ref name="p8">Simone S. Boks, Dammis Vroegindeweij, Bart W. Koes, et al. MRI Follow-Up of posttraumatic Bone Bruises of the knee in General Practice. AJR 2007; 189:556–562 Grades of recommendation B</ref> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

The treatment of a bone bruise consists of [[RICE]], pain relief and/or anti-inflammatories as prescribed by a medical practitioner and load restriction dependant on the circumstances of the injury. <sub><ref name="p0">The Basics of Bone Bruises; Grades of recommendation F | |||

http://bruises.knowingfirstaid.com/permalink.php?article=Bone%20Bruises.txt</ref></sub> The time for the resolution of a bone bruise is variable. Literature suggests that the healing time to completely resolve this injury can take anywhere between three weeks to up to two years after the trauma.<sub><ref name="p3">V. Mandalia, A.J.B. Fogg, R. Chari, J. Murray, A. Beale, J.H.L. Henson. Bone bruising of the knee. Clinical Radiology 2005; 60, 627–636 Grades of recommendation:A</ref><ref name="p6" /></sub> | |||

< | |||

< | |||

</ | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /><br> | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Vrije Universiteit Brussel Project|Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Injuries]] | |||

[[Category:Primary Contact]] | |||

[[Category:Fractures]] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:55, 3 August 2020

Original Editors - Laurien Henau as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project.

Top Contributors - Laurien Henau, Claire Knott, Admin, Rik Van der Hoeven, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Wanda van Niekerk and Lucinda hampton - .

What is a bone bruise?[edit | edit source]

A bone bruise is a type of bone injury.

- Other examples of bone injuries include stress fractures, osteochondral fractures and a variety of different patterns of bone fractures.[1]

- A bone bruise is characterised by three different kinds of bone injuries including: sub-periosteal hematoma, inter-osseous bruising and a sub-chondral lesion, or a combination of these. [2]

- A bone bruise is differentiated from the alternative fracture types in that only some of the trabeculae are broken.[3]

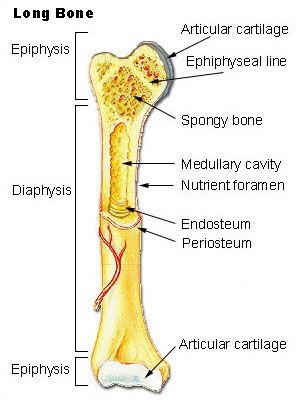

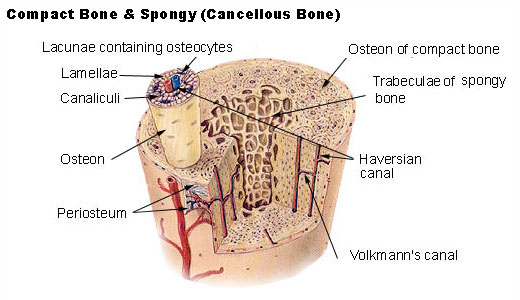

Clinically Relevant Physiology[edit | edit source]

Bone tissue is a specialised form of connective tissue that is made up of an organic matrix (collagen and glycosaminoglycans) and inorganic minerals (calcium and phosphate). [4] An adult human skeleton contains 80% cortical bone and 20% trabecular bone. Both types of bone are composed of osteons. Cortical bone is the solid type of bone and trabecular bone resembles honeycomb which is comprised of a network of trabecular plates and rods. Read more about the histology and physiology of bone here.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The most common cause of bone bruise is trauma however the condition can also be associated with normal stress loading and haemophilia A and B.[5]

The most commonly affected area is the lower limb. [6]

Patients with a bone bruise tend to have protracted clinical recovery, with more effusion and a slower return of motion. [1]

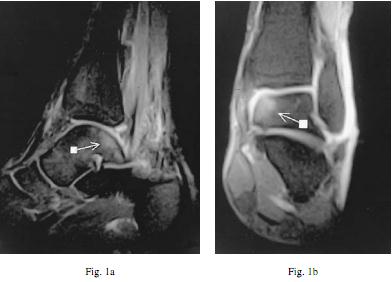

In patients with ACL rupture there is an 80% probability of concurrent associated bone bruising at the femoral condyle or tibial plateau.[1][4] According to Boks et al. 2007, the presence of bone bruising in these zones is the most important secondary sign in the diagnosis of ACL injury.

MRI with white arrow indicating presence of bone bruising in the (a) post-lateral talus area and (b) the caudal tibia epiphysis.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

| Bone Injury Type | Characteristics | Typical Injury Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-periosteal hematoma | A concentrated collection of blood underneath the periosteal of the bone. | Direct high-force trauma to the bone |

| Inter-osseous bruising | Damage of the bone marrow. The blood supply within the bone is damaged, and this causes internal bleeding. | Repetitive compressive force on the bone (extreme pressure on regular base). |

| Sub-chondral lesion | Lesion occurs beneath the cartilage layer of a joint. | Extreme compressive force or rotational mechanism such as testing (shearing force) that literally crushes the cells

Force causes separation of the cartilage (or ligament) and the underlying bone, plus bleeding when the energy of the impact extends into the bone. |

For the all bone injuries, incidence rates tend to be higher amongst professional athletes and those that run and jump frequently on hard surfaces, for example football and basketball players. [1][2]

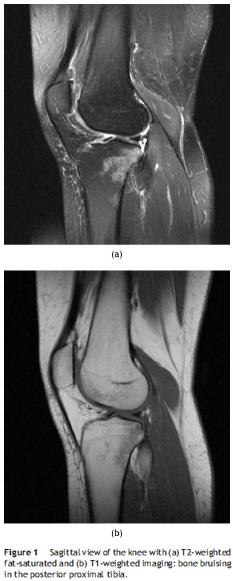

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

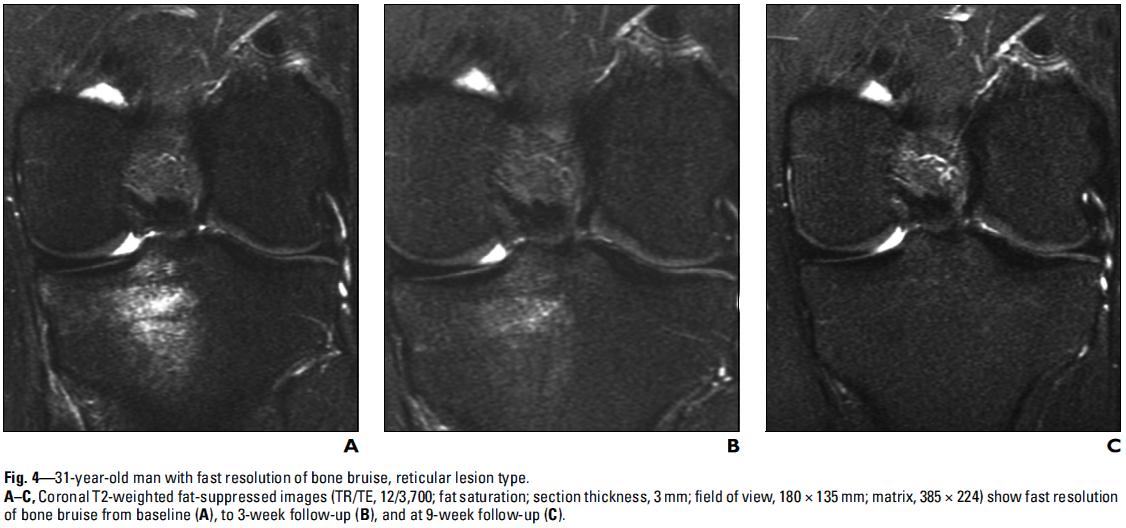

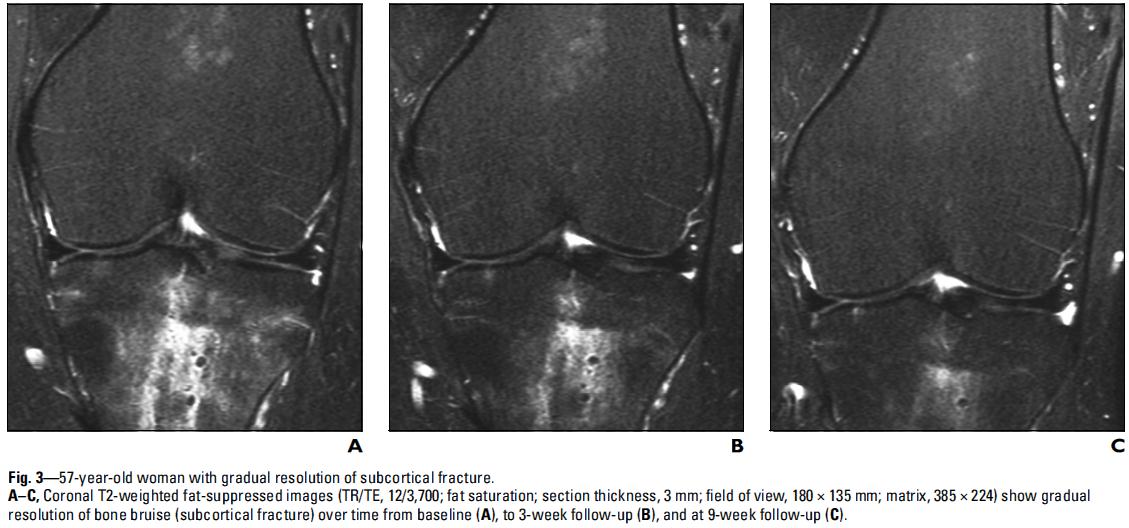

Although an x-ray should identify whether or not there is a bone fracture, a bone bruise is not able to be diagnosed using x-ray imaging. The current "gold standard" diagnostic imaging method for bone bruises is the MRI, in particular T2-weighted fat-suppressed images or T1-weighted imaging.[4]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of a bone bruise consists of RICE, pain relief and/or anti-inflammatories as prescribed by a medical practitioner and load restriction dependant on the circumstances of the injury. [8] The time for the resolution of a bone bruise is variable. Literature suggests that the healing time to completely resolve this injury can take anywhere between three weeks to up to two years after the trauma.[1][2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 V. Mandalia, A.J.B. Fogg, R. Chari, J. Murray, A. Beale, J.H.L. Henson. Bone bruising of the knee. Clinical Radiology 2005; 60, 627–636 Grades of recommendation:A

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 V. Mandalia, J.H.L. Henson. Traumatic bone bruising – A review article, European Journal of Radiology 2008; 67; 54–61 Grades of recommendation A

- ↑ Janice Polandit, 5 Things You Need to Know About a Bone Bruise, 2011; http://www.livestrong.com/article/5521-need-bone-bruise/ Grades of recommendation F

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 L.C. Jungueira and J. Carneiro, “Functional Histology” 2010; 167

- ↑ Prof. Dr. S. Van Creveld and Dr. M. Kingma Subperiostal haemorrhage in haemophilia A and B. Ned. T. Geneesk. 105. I. 22. 1961; 1095-1098 Grades of recommendation F

- ↑ Christoph Rangger, Anton Kathrein, Martin C Freund, et al. Bone Bruise of the Knee. Acta Orthop Scand 1998; 69(3) : 291-294. Grades of recommendation B

- ↑ Simone S. Boks, Dammis Vroegindeweij, Bart W. Koes, et al. MRI Follow-Up of posttraumatic Bone Bruises of the knee in General Practice. AJR 2007; 189:556–562 Grades of recommendation B

- ↑ The Basics of Bone Bruises; Grades of recommendation F http://bruises.knowingfirstaid.com/permalink.php?article=Bone%20Bruises.txt