Phantom Limb Pain

Original Editor - Peter Le Feuvre

Top Contributors - Admin, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Vidya Acharya, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Lauren Lopez and Jess Bell

Post amputation pain and phantom limb pain: key messages[edit | edit source]

Pain is an inevitable consequence of amputation, and for many, pain will not just result from the trauma of the surgery, but will also include a neuropathic presentation known as phantom limb pain (PLP). When amputation has resulted from a traumatic incident, such as in a disaster setting, this can be complicated by co-existing injury to the same limb or other parts of the body. For the physiotherapists involved in the early and post acute stages of rehabilitation, the challenge is determining the nociceptive and neuropathic causes which require attention in order to manage the patient and so enable effective rehabilitation to occur.

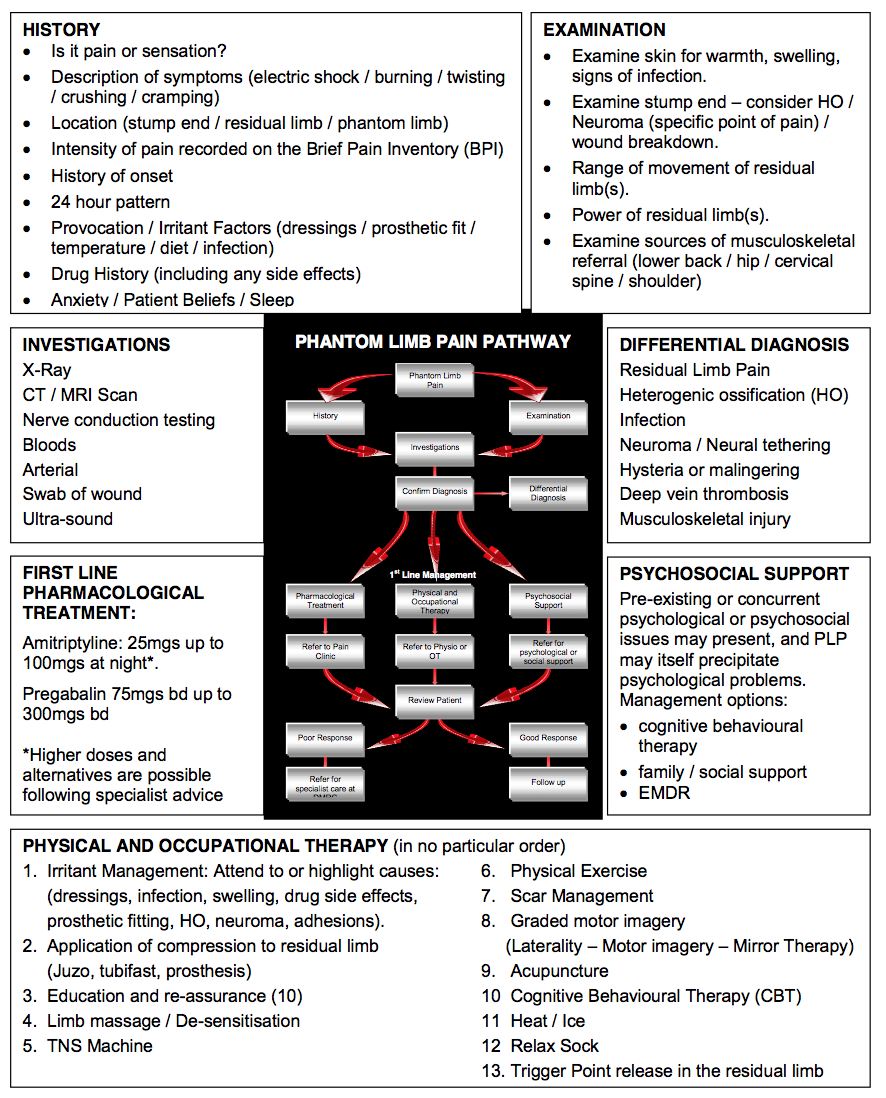

Table 1 contains an assessment approach which may help clinicians to determine the correct course of action required with a patient. The assessment must commence by accurately identifying that PLP is indeed the issue. A knowledge of the different characteristics of each pain presentation (below) will help the clinician to establish this from an assessment of their history:

- Post-Amputation Pain: Post-amputation pain at the wound site should also be distinguished from pain in the residual limb and the phantom limb. After amputation, all three may occur together

- Residual Limb Pain: PLP is often confused with pain or sensation in the areas adjacent to the amputated body part. This is known as residual limb (RLP) or stump pain and its intensity is often positively correlated with PLP.

- Phantom Limb Sensation: This is a normal experience for the majority of amputees, but it is not a noxious sensation, which might be described by the patient as unpleasant. Often it can be described as a light tingling sensation, or In such cases re-assurance is the key.

- Phantom Limb Pain: Classified as neuropathic pain, whereas RLP and post-amputation pain are classified as nociceptive pain. PLP is often more intense in the distal portion of the phantom limb and can be exacerbated or elicited by physical factors (pressure on the residual limb, time of day, weather) and psychological factors, such as emotional stress. Commonly used descriptors include sharp, cramping, burning, electric, jumping, crushing and cramping.

The assessment should then seek to establish the principle driver(s) of the PLP. These may be centrally driven adaptation, peripheral sensitisation, mental state or social concerns, and musculoskeletal factors. Treatment should target these drivers. See table 2 for more detail and suggested treatments.

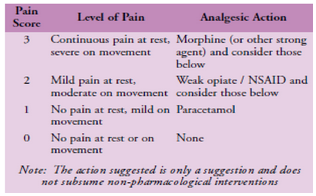

Objective Measurement: In addition to completing a pain chart, measurement of pain intensity is helpful. The brief pain inventory (BPI) is one method of charting the intensity of symptoms, however it takes time to administer. The 0-3 VAS is an easy to administer scale which highlights when intervention is required. It is also easy to fit it with the WHO pain ladder (Figure 1). In short, scores of 0 and 1 (nil to mild pain) require no intervention, 2 and 3 (moderate to severe) requires immediate action.

Table 1 - Summary of assessment process and treatments for PLP

Figure 1 - Pain scale and WHO pain ladder

An aid to clinical reasoning in phantom limb pain[1][edit | edit source]

Simply discriminating between RLP and PLP is more complex than it appears. Both often coexist and RLP may provoke PLP. Eliminating the causes of RLP is therefore the priority as this will resolve or lessen PLP which is respondent to peripheral aggravators. It also shows the degree to which central factors may have an ongoing influence.

Immediate post-amputation management demands early effective analgesia and adjunctive measures include managing oedema using elastic stump socks, semi-rigid dressings and rigid plaster casts. Post-acute management requires attention to both intrinsic and extrinsic causes of RLP.

Extrinsic RLP will result from complications of wound healing and so infection must be excluded. Tissue load and sheering forces placed on the limb due to a poor prosthetic fit will also evoke pain. A prosthetic review will improve fit and enable sensitised structures to be offloaded. Scar formation can also cause pain, particularly where there is nerve entrapment, or adhesions reducing the mobility of soft tissues. In either case, scar management using soft tissue massage and moisturiser is recommended; silicone treatment can also be added if required. Besides improving tissue mobility, massage can be used to desensitise the residual limb. Intrinsic causes of RLP can include ischaemia, joint dysfunction proximal to the residual limb, stress fracture, osteomyelitis and wound dehiscence. Occasionally where the bone has been improperly trimmed or formation of bone in extraskeletal soft tissue has occurred (HO), then pain may result in high-pressure areas. Investigations will be required and revision surgery may be considered; alternatively, prosthetic adjustment can be used to unload pressure areas.

Neuroma is the most common cause of intrinsic RLP. Ectopic discharge may evoke a neuropathic response causing PLP. Neuroma formation after amputation is normal, but when it becomes sensitised to mechanical or chemical stimuli, often exacerbated by entrapment, then problems ensue. Pain is intermittent and variable, but diagnosis is confirmed by a specific site of tenderness on palpation, which can be confirmed with an injection of local anaesthetic into the site. Surgical referral can be considered, but massage, vibration, acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may also effectively desensitise the area. It is also work excluding muscle tension / spasm as a cause by assessing local and trigger points within the soft tissue.

Combining physical and occupational therapy with a cognitive understanding of the condition will amplify the effects of treatment. We should aim to equip and empower the patient, informing them about their condition and how they can take control while seeking to alter destructive or erroneous beliefs and actions. Common self-treatment strategies can include wearing an elastic stump sock to minimise volume changes in the residual limb, stump massage, mental imagery of the phantom limb and taking physical exercise.

Visualisation of limb movement and prosthetic use can reduce PLP, this is especially the case with upper limb amputees. Joint dysfunction proximal to the residual limb and prosthetic fit will however undermine this effect. Good prosthetic use is vital. Normalising the gait pattern is, in part, due to prosthetic fit and alignment. It is also dependent on good proprioception, correct motor patterning and symmetrical movement control enabling dissociation of movement between trunk and limb. In turn, the residual limb(s), trunk and spinal segments must have sufficient range and control of movement to achieve a symmetrical gait pattern. Where limb wearing is not possible, the therapist should engage their creativity to seek ways of simulating visual and even motor stimuli in order to mimic the use of the limb.

Mirror therapy is a therapeutic intervention which has been shown to affect motor and sensory processes through the relative dominance of the visual input it provides. The effect is created by viewing a reflection of the intact limb through a mirror placed where the amputated limb would have existed. Most of the evidence for this intervention comes from case studies and anecdotal data with only a couple of well controlled studies. Moseley argued that while mirrored movements may expose the cortex to sensory and motor input, the therapeutic effect is magnified if cortical networks are gradually activated using limb recognition, motor imagery and finally, mirrored movement. This sequence of cortical exposure has become known as graded motor imagery. Clinicians wishing to add this programme to their treatment repertoire can find resources at http://www.noigroup.com

A NOTE ON MEDICATION: UK military pain management system encourages the use of antineurppathic medication such as pregabalin and amitriptyline as early as possible. First-line treatment is a trial of up to 300 mg twice daily of pregabalin and up to 150 mg of amitriptyline at night. If pregabalin is insufficient, or depression is a problem, duloxetine may be used. Opioids are of variable help. It may be that tapentadol will prove to be beneficial, but it is too early to say clearly. While pharmacological agents can be of use, the way they are used is even more important. Pharmacological agents are not going to remove all pain. What really matters is that the agents enable the patient to ‘do more’. In this way they can be likened to the old confectionary advertisement that suggested it allows you to ‘work, rest and play’; the point being if the pharmacological agents do not have this action there is no point taking them. Often a good starting point is to enable good sleep. You can always have a good night after a bad day, but never a good day after a bad night.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ e Feuvre P, Aldington D. Know Pain Know Gain: proposing a treatment approach for phantom limb pain. J R Army Med Corps 2014; 160(1):16-21