Tetanus

Original Editors - Natalie Gutmann from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Natalie Gutmann, Elaine Lonnemann, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1 and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Tetanus is an infection that causes state of generalised hypertonia that presents in the form of painful muscle spasms of the jaw and neck. The disease most commonly occurs in those who are not vaccinated or in the elderly with waning immunity. Recently, vaccination campaigns have decreased the incidence and prevalence of tetanus worldwide. Symptoms are caused by toxins produced by the bacterium, Clostridium tetani.[1] The most common way the bacterium enters the body is through wounds which are susceptible to infection if they are: “contaminated with soil, feces, or saliva, puncture wounds including unsterile injection sites, devitalized tissue including burns, avulsions and degloving injuries”.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Once C. tetani enters the body, it secretes the toxins, tetanospasmin, and tetanolysin, causing the characteristic “tetanic spasm,” a generalized contraction of agonist and antagonistic muscles.

Once the bacteria has entered the body the incubation period may range from days to months. The average incubation period is around 4-14 days. The incubation period is shorter the closer the injury site is to the CNS.[3][4] A shorter incubation period usually correlates with poor prognosis due to a more severe disease.[5]

At the site of inoculation, tetanus spores enter the body and germinate in the wound. Germination needs particular anaerobic conditions, such as dead and devitalized tissue that has low oxidation-reduction potential. After germination, they release tetanospasmin into the bloodstream. Tetanospasmin affects the nerve and muscle motor endplate interaction, causing the clinical syndrome of rigidity, muscle spasms, and autonomic instability. On the other hand, tetanolysin damages the tissues.[1]

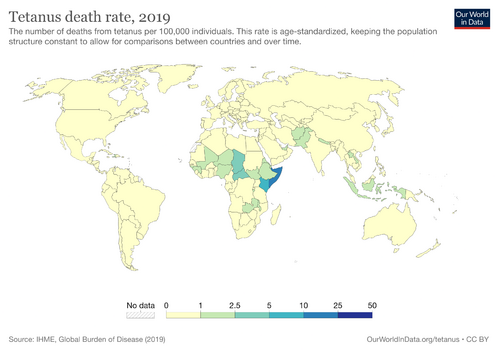

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Although tetanus affects people of all ages; however, the highest prevalence is seen in newborns and young persons. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports improvement in mortality rates from tetanus, related with combative vaccination campaigns in recent years. The WHO estimates worldwide tetanus deaths in 1997 at around 275,000 with improved rates in 2011 at 14,132 cases.[1]

Presentation[edit | edit source]

The incubation period of tetanus varies between 3 and 21 days after infection, with most cases occur within 14 days.

Symptoms can include:

- jaw cramping or the inability to open the mouth

- muscle spasms often in the back, abdomen and extremities

- sudden painful muscle spasms often triggered by sudden noises

- trouble swallowing

- seizures

- headache

- fever and sweating

- changes in blood pressure or fast heart rate.[6]

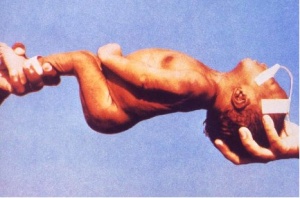

Neonatal tetanus: a form of generalized tetanus which also has a high fatality rate.[2] The diagnosis is determined from the symptoms that present. When the baby is born they are able to suck and swallow normally for 2-3 days and then they lose that ability. The symptoms of neonatal tetanus are muscle rigidity and spasms which appear around "4-14 days after birth”.[4][7] The most common way neonatal tetanus occurs is due to non- immune mothers and poor hygiene during the delivery process.[2] Most of the cases of infected infants is a result of infection of the unhealed stump of the umbilical cord especially if the cord has been cut with unsterile instruments. Neonatal tetanus is very common in third world countries.[4]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Tetanus is a medical emergency requiring:

- Care in the hospital

- Early intramuscular or intravenous administration of the human tetanus immunoglobulin (HTIG). Removes released tetanospasmin toxin; however, it does not affect the toxin that is already bound to the central nervous system.

- Aggressive wound care

- Antispasmodics eg benzodiazepines, baclofen, vecuronium, pancuronium, and propofol

- Antibiotic therapy (metronidazole, slows progression of disease)[1]

- Tetanus vaccination.

Patients with severe symptoms need to be admitted to the ICU for close monitoring and mechanical ventilation. Healthcare providers need to provide supportive care, especially for patients with autonomic instability (labile blood pressure, hyperpyrexia, hypothermia).

Rehabilitation may take weeks or months.[6]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are no specific laboratory or diagnostic tests used to diagnosis tetanus. The diagnosis is made based on clinical signs and symptoms and not on the confirmation of the bacteria C. tetani in the body. [4][8]“C. tetani is recovered from the wound in only 30% of cases and can be isolated from patients who do not have tetanus.”[4]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Currently research is limited on the Physical therapy management of individuals with tetanus. Cardiopulmonary physical therapy can be used to help in the prevention of respiratory complications.[9] Physical therapy can also be used to help with muscle rigidity and spasms.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bae C, Bourget D. Tetanus.[Updated 2020 May 28]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021.Available:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/29997/ (accessed 17.12.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ewcombe P. Treating and preventing tetanus in A&E. Emergency Nurse. October 2004;12(6):23-29.

- ↑ Wakim N, Henderson S. Tetanus. Topics in Emergency Medicine. July 2003;25(3):256-261.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 CDC. Tetanus: Questions and Answers. November 2010.www.immunize.org.

- ↑ Linnenbrink T, McMichael M. Tetanus: pathophysiology, clinical signs, diagnosis, and update on new treatment modalities. Journal of Veterinary Emergency & Critical Care. September 2006;16(3):199-207.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 WHO Tetanus Available:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tetanus (accessed 17.12.2022)

- ↑ Tetanus vaccine. Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire / Section D'hygiène Du Secrétariat De La Société Des Nations = Weekly Epidemiological Record / Health Section Of The Secretariat Of The League Of Nations. May 19, 2006;81(20):198-208. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Grunau B, Olson J. An interesting presentation of pediatric tetanus. CJEM: Canadian Journal Of Emergency Medical Care = JCMU: Journal Canadien De Soins Médicaux D'urgence. January 2010;12(1):69-72. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Cook T, Protheroe R, Handel J. Tetanus: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Anaesthesia. September 2001;87(3):477-487. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2011.