Classification of Shoulder Pain

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Shaimaa Eldib, Kim Jackson, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, Tony Lowe, Fasuba Ayobami, Claire Knott, Stacy Schiurring and Rachael Lowe

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Classification provides a general framework for identifying subgroups of patients based on the primary goal of treatment, with the ultimate aim of matching indivuals to specific interventions from which they are most likely to benefit [1]. Diagnostic algorithms and classification may be beneficial to clinical decision making and allows clinicians to easily identify the correct intervention strategy, guide treatment decision making and inform a patient’s prognosis. Additionally communication among health care providers, researchers, and those utilizing research findings is possible through the use of diagnostic categories.[2]

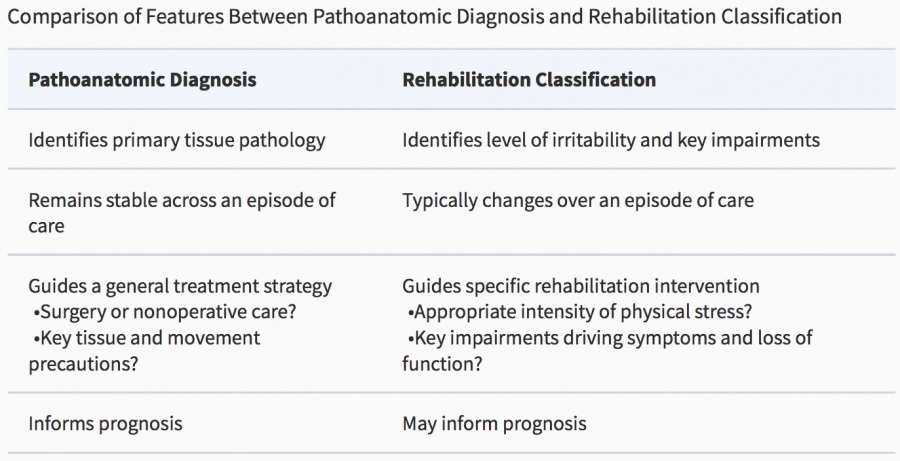

Evidence for the conservative management of shoulder pain currently does not support any particular approach. There has been a shift from the pathoanatomical model of diagnosis towards treatment or rehabilitation-oriented classification that will inform patient management.[2] This form of classification provides a general framework for identifying subgroups of patients based on the primary goal of treatment, with the ultimate aim of matching individuals to specific interventions from which they are most likely to benefit, which can change as they progress through the different stages of treatment.[2]

Classification Types[edit | edit source]

Pathoanatomic Model[edit | edit source]

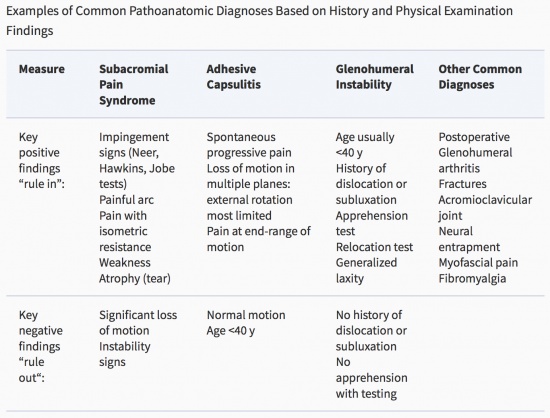

Definition of shoulder conditions and the nomenclature used to describe them is extremely varied, and as a result there have been many attempts at standardizing the use of diagnostic labels utilising classication systems. Traditionally these classification systems or diagnostic categories such as those proposed by Waris et al.[3], Cyriax [4], Neer [5], ViikariJuntura [6], Silverstein [7], McCormack et al. [8], Uhthoff & Sarkar [9], ICD10 [10] and Palmer et al. [11] were all based on a pathoanatomic medical model aimed at identifying the pathologic tissues which was responsible for the shoulder pain[12]. The pathoanatomical model looks to explain the source of the patients presenting signs and symptoms based on the presence of specific structural pathology identified through isolated or combined physical examination, imaging and histopathological analysis.[12]

Diagnostic labels based on tissue-specific pathology fail to accurately classify the patient into subgroups for clinical decision-making and many of these classification systems based on the pathoanatomic model for shoulder pain have been shown to be unreliable resulting in a lack of diagnostic consistency in relation to shoulder pain. [13] Recent research suggests that the pathoanatomic model may not provide a classification systems or diagnostic categories that effectively guide treatment decision making in rehabilitation management of shoulder pain.[2]

Shoulder disorders, classified through a pathoanatomic diagnosis infer that patients with the same tissue pathology form a homogeneous group which guide decisions for treatment and prognosis.[2][12]This form of classification suggests that patients with the same pathology should be managed in the same way, have similar prognoses and that the diagnosis remains static throughout the whole period of their care. It is also suggested that it is this pathology which explains the both the symptoms and impairments (activity limitations and participation restrictions) experienced by the patient and that correcting the pathology will improve the symptoms and impairments.[2][15] The pathoanatomic diagnosis may be inadequate for guiding rehabilitation as the categories encompass patients with similar tissue pathology, but within each pathoanatomic category, there often exists a heterogeneous group of patients with different or varying degrees of impairment and pain that require a different rehabilitation approach rather than managed in the same way.

The International Classication of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) provides the following examples of Pathoanatomic Diagnostic Labels for Shoulder Pain; [10]

- M75.0 Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder (Frozen Shoulder, Periarthritis of the Shoulder)

- M75.1 Rotator Cuff Syndrome (Rotator Cuff or Supraspinatus Tear or Rupture (Complete or Incomplete) not specified as Traumatic, Supraspinatus Syndrome)

- M75.2 Bicipital Tendinitis

- M75.3 Calcific Tendinitis of Shoulder, Calcified Bursa of the Shoulder

- M75.4 Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder

- M75.5 Bursitis of Shoulder

- M75.8 other Shoulder Lesions

Treatment / Rehabilitation Model[edit | edit source]

Recent evidence suggests a poor relationship between diagnostic pathoanatomic classification and chosen rehabilitation interventions among orthopedic physical therapists.and as such this suggests that clinical decision making based on a clinical diagnosis and use of diagnostic labels arrived at using special orthopaedic tests is flawed.[2][12] In line with this current researchers have suggested classification models based on treatment and rehabilitation subgroups including Hughes et al. [16], Schellingerhout et al. [15], Lewis [17], and May [18].

Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification: Shoulder Disorders (STAR–Shoulder)[edit | edit source]

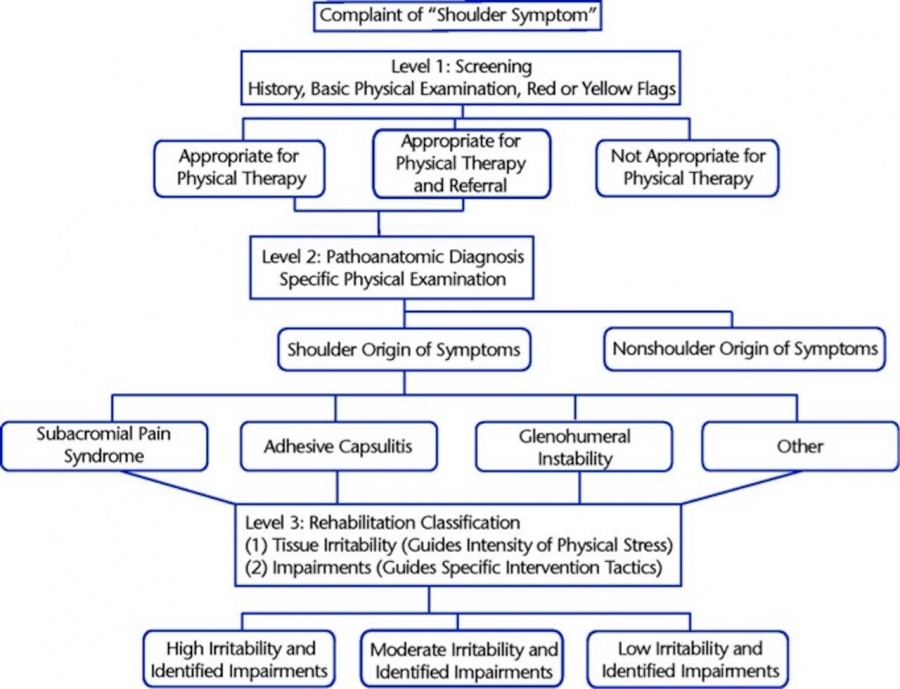

Mc Clure and Michener propose a Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification of Shoulder Pain (STAR–Shoulder), incorporating both the pathoanatomic and treatment / rehabilitation models in conjunction which are both derived through Screening comprising history and physical assessment :[14]

1. Screening[edit | edit source]

Incorporates the history and basic physical assessment in order to gain a overall impression of the problem and identify potential “red flags” and “yellow flags”, to determine if the are signs and symptoms are consistent with a musculoskeletal problem amenable to rehabilitation rather than a more serious disorder requiring onward referral

2. Pathoanatomic Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Derived from a combination of history, special orthopaedic tests, and results of imaging where available, the pathoanatomic diagnosis as we discussed above is made based on identifying the presumed tissue pathology generating the signs and symptoms. Often it is at this stage where primary intervention decisions such as surgery versus conservative treatment, which may include medication, corticosteroid injection, rest, and rehabilitation are determined.[14]

3. Rehabilitation Classification[edit | edit source]

is used to guide the intensity and specific focus of rehabilitation.Based on the irritability rating and primary impairments this classification aims to determine the specific intervention strategies and approach.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

As we have discussed specific pathoantomic diagnosis and classification can be difficult. Inconsistent relationships between tissue pathology and impairments limit the sole use of pathology for clinical decision making in rehabilitation. Many shoulder pathologies present with similar examination findings, but vary widely in their outcomes and require different intervention approaches.[21] The pathoanatomic diagnosis alone cannot fully direct the intensity and specific intervention tactics used in the treatment of patients with musculoskeletal shoulder disorders. Physical assessment of the shoulder is based on the premise that isolation of specific anatomical structures is possible during the physical exam using orthopedic tests that apply compression, stretching or isolated contraction to selected tissues. [12] However,as we have seen clinical tests designed to assess structural integrity and pain response are unlikely to selectively isolate an individual tissue from adjacent structures, confounding the ability to determine which structures are involved in the patient’s symptoms and the reliability of these tests has generally been shown to be limited [13–15], the diagnostic validity moderate at best [16,17], and the anatomical basis for most tests has not been validated.[12][22] The difficulties associated with generating a relevant structurally specific diagnosis relating to the shoulder are evident and now consistently reported across a wide body of literature.

Given that shoulder pain is difficult to accurately diagnose based on pathology alone, it has been argued that there is a need to shift from a pathoanatomic, diagnostic approach towards a prognostic approach that is treatment or rehabilitation focussed.[23] An important point of consideration in this from a Physiotherapy perspective is that as physiotherapists we focus on movement- related impairments rather than structural anatomy as we are unable to influence the shape of the acromion, remove acromial spurs or restore the integrity of the labrum. More specifically physiotherapists try to influence motor control, soft tissue strength, flexibility, functional osteokinematics and arthrokinematics and as such our treatment strategies are grounded more on the identified impairments, tissue irritability and patient-related goals and expectations. Considering the fact that impair- ments in the shoulder are often related to abnormal scapulothoracic or gleno- humeral kinematics, muscle performance deficits or kinetic chain dysfunctions, the challenge will be to identify impair- ment patterns to classify patients based on movement dysfunction instead of pathoanatomic diagnoses, and to estab- lish reliability and validity of these classifications.

The idea that a structurally specific diagnosis is needed before a successful treatment regime is implemented has been questioned,[21] but McClure and Michener believe the pathoanatomic diagnosis is still an essential element of the process for classifying shoulder pain. The STAR Classification System is founded with the pathoanatomic diagnosis and then is expanded to aid rehabilitation treatment decision making by classifying the level of irritability and identification of impairments. [14]

Future classification labelling should consider both pathoanatomical diagnosis and classification based on relevant impairments to drive treatment decision-making. Classifying patients into subcategories will help the clinician to determine the treatment strategy. Moreover, over the course of an episode of care, patients may shift from one category to another, or be considered appropriate for two categories at the same time.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Childs MJ, Fritz JM, Piva SR, Whitman JM. Proposal of a Classification System for Patients with Neck Pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004 Nov;34(11):686-700.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 McClure, P. W., & Michener, L. A. (2015). Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification: Shoulder Disorders (STAR-Shoulder). Physical Therapy, 95(5), 791–800. http://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140156

- ↑ Waris P, Kuorinka I, Kurppa K, et al: Epidemiological screening of occupational neck and upper limb disorders, Scand J Work Environ Health 6(suppl):25–38, 1979

- ↑ Cyriax J: Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, ed 8, London, 1982, Baillière Tindall

- ↑ Neer CS: Impingement lesions, Clin Orthop Relat Res 173:70–77, 1983

- ↑ ViikariJuntura E: Neck and upper limb disorders among slaughterhouse workers: an epidemiologic and clinical study, Scand J Work Environ Health 9:283–290, 1983

- ↑ Silverstein BA: The prevalence of upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders in industry (thesis), 1985, The University of Michigan, Occupational Health and Safety

- ↑ McCormack RR, Inman RD, Wells A, et al: Prevelance of tendinitis and related disorders of the upper extremity in a manufacturing workforce, J Rheumatol 19:958–964, 1990

- ↑ Uhthoff HK, Sarkar K: An algorithm for shoulder pain caused by soft tissue disorders, Clin Orthop 254:121–127, 1990

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 WHO (World Health Organization): International Classication of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision, 2010. http://apps.who.int/classi cations/ apps/icd/icd10online/ (accessed 31 Nov 2017).

- ↑ Palmer K, WalkerBone K, Linaker C, et al: The Southampton Examination Schedule for the Diagnosis of Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck and Upper Limb, Ann Rheum Dis 59:5–11, 2000.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Newton PA. Management of Shoulder and Shoulder Girdle Disorders. Maitland's Peripheral Manipulation E-Book: Management of Neuromusculoskeletal Disorders. 2013 Aug 27;2:142.

- ↑ Klintberg IH, Cools AM, Holmgren TM, Holzhausen AC, Johansson K, Maenhout AG, Moser JS, Spunton V, Ginn K. Consensus for Physiotherapy for Shoulder Pain. International Orthopaedics. 2015 Apr 1;39(4):715-20.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 McClure PW, Michener LA. Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification: Shoulder Disorders (STAR–Shoulder). Physical Therapy. 2015 May 1;95(5):791-800.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Thomas S, et al: Lack of Uniformity in Diagnostic Labelling of Shoulder Pain: Time for a Different Approach, Man Ther 13:478–483, 2008.

- ↑ Hughes PC, Taylor NF, Green RA: Most Clinical Tests Cannot Accurately Diagnose Rotator Cuff Pathology: A Systematic Review, Aust J Physiother 54:159–170, 2008.

- ↑ Lewis JS: Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy / Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Is it Time for a New Method of Assessment? Br J Sports Med 43:236–241, 259–264, 2009.

- ↑ May S, Chance Larsen K, Littlewood C, et al: Reliability of Physical Examination Tests used in the Assessment of Patients with Shoulder Problems: A Systematic Review, Physiotherapy 96(3):179–190, 2010.

- ↑ From: Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification: Shoulder Disorders (STAR–Shoulder) Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):791-800. doi:10.2522/ptj.20140156 Phys Ther | © 2015 American Physical Therapy Association Available from:https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/95/5/791/2686487 [accessed 30 November 2017]

- ↑ McClure PW, Michener LA. Staged Approach for Rehabilitation Classification: Shoulder Disorders (STAR–Shoulder). Physical Therapy. 2015 May 1;95(5):791-800.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Littlewood, C. (2013). Contractile Dysfunction of the Shoulder (Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy): An Overview. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 20(4), 209–213. http://doi.org/10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000005

- ↑ Bahat, H. S. (2016). The Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure (SSMP): A Reliability Study. Journal of Novel Physiotherapies, s3, 1–7. http://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7025.S3-011

- ↑ Shoulder Pain and Regional Interdependence: Contributions of the Cervicothoracic Spine. (2014). Shoulder Pain and Regional Interdependence: Contributions of the Cervicothoracic Spine. Journal of Yoga & Physical Therapy, 05(01), 1–2. http://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7595.1000179