Resisted Exercise Initiative (RExI): Difference between revisions

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) (Correct errors and omissions) |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

==== 1-COPD ==== | ==== 1-COPD ==== | ||

'''COPD Key Points'''<ref>Camp PG, Reid WD, Chung F, Kirkham A, Brooks D, Goodridge D, Marciniuk DD, Hoens AM. Clinical decision-making tool for safe and effective prescription of exercise in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from an interdisciplinary Delphi survey and focus groups. Physical therapy. 2015 Oct 1;95(10):1387-96.</ref> | '''COPD Key Points'''<ref>Camp PG, Reid WD, Chung F, Kirkham A, Brooks D, Goodridge D, Marciniuk DD, Hoens AM. Clinical decision-making tool for safe and effective prescription of exercise in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from an interdisciplinary Delphi survey and focus groups. Physical therapy. 2015 Oct 1;95(10):1387-96.</ref> | ||

* Performing pursed lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing can increase breathing efficiency<ref name=":7">Thompson WR, Sallis R, Joy E, Jaworski CA, Stuhr RM, Trilk JL. Exercise is medicine. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2020 Sep;14(5):511-23.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827620912192</ref> | * Performing pursed lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing can increase breathing efficiency .<ref name=":7">Thompson WR, Sallis R, Joy E, Jaworski CA, Stuhr RM, Trilk JL. Exercise is medicine. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2020 Sep;14(5):511-23.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827620912192</ref> | ||

* Increasing oxygen therapy during exercise may help to prevent exercise-induced hypoxemia. | * Increasing oxygen therapy during exercise may help to prevent exercise-induced hypoxemia. | ||

* Instruct the patient to avoid extreme weather conditions and schedule exercise sessions during mid-late morning hours. | * Instruct the patient to avoid extreme weather conditions and schedule exercise sessions during mid-late morning hours. | ||

| Line 273: | Line 273: | ||

==== 2-Cardiac ==== | ==== 2-Cardiac ==== | ||

'''Cardiac Key Points'''<ref name=":7" /> | '''Cardiac Key Points''':<ref name=":7" /> | ||

* Patients with left ventricular outflow, decompensated chronic heart failure or unstable dysrhythmias should not exercise. | * Patients with left ventricular outflow, decompensated chronic heart failure or unstable dysrhythmias should not exercise. | ||

* Patients with significant aortic stenosis should avoid strength training. | * Patients with significant aortic stenosis should avoid strength training. | ||

* Patients who have had a myocardial infarction should closely monitor intensity level and stay within the patient's recommended exercise heart rate range . | * Patients who have had a myocardial infarction should closely monitor intensity level and stay within the patient's recommended exercise heart rate range. | ||

* Patients with congestive heart failure should closely monitor the intensity level and adjust workout if feeling fatigued. Instruct patient to stop exercising if they experience chest pain/angina. | * Patients with congestive heart failure should closely monitor the intensity level and adjust workout if feeling fatigued. Instruct patient to stop exercising if they experience chest pain/angina. | ||

* Patients with atrial fibrillation should adjust how hard and how long exercises are performed based on how they feel. | * Patients with atrial fibrillation should adjust how hard and how long exercises are performed based on how they feel. | ||

* Exercise should be performed without Valsalva maneuver (i.e. exhaling against a closed glottis). | * Exercise should be performed without Valsalva maneuver (i.e. exhaling against a closed glottis). | ||

* Instruct the patient to stop exercising immediately if experiencing angina . | * Instruct the patient to stop exercising immediately if experiencing angina. | ||

* Upper body exercises may precipitate angina more readily than lower body exercises because of a higher pressor response. | * Upper body exercises may precipitate angina more readily than lower body exercises because of a higher pressor response. | ||

* An extended warm up and cool down may reduce the risk of angina or other cardiovascular complications following exercise. | * An extended warm up and cool down may reduce the risk of angina or other cardiovascular complications following exercise. | ||

| Line 288: | Line 288: | ||

==== 3-Stroke ==== | ==== 3-Stroke ==== | ||

'''Stroke Key Points'''<ref>Brown G, Brunton K, French E, Gilmore P, Gregor T, Howe JA, Kelloway L, Levy J, Matthews J, McCullough C, McNorgan C. Post Stroke Community-Based Exercise Guidelines. InINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF STROKE 2016 Sep 1 (Vol. 11, pp. 64-64). 1 OLIVERS YARD, 55 CITY ROAD, LONDON EC1Y 1SP, ENGLAND: SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD.</ref><ref name=":7" /> | '''Stroke Key Points''':<ref>Brown G, Brunton K, French E, Gilmore P, Gregor T, Howe JA, Kelloway L, Levy J, Matthews J, McCullough C, McNorgan C. Post Stroke Community-Based Exercise Guidelines. InINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF STROKE 2016 Sep 1 (Vol. 11, pp. 64-64). 1 OLIVERS YARD, 55 CITY ROAD, LONDON EC1Y 1SP, ENGLAND: SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD.</ref><ref name=":7" /> | ||

* Add task-oriented circuit training to improve transfer skills, mobility and ADLs/functional tasks. | * Add task-oriented circuit training to improve transfer skills, mobility and ADLs/functional tasks. | ||

* Avoid putting the most challenging or complex exercises at the end of an exercise program as the patient might be tired-potentially increasing risk of falls, injury and/or undue fatigue.<ref>Eng JJ. Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) program for stroke. Topics in geriatric rehabilitation. 2010;26(4):310</ref> | * Avoid putting the most challenging or complex exercises at the end of an exercise program as the patient might be tired-potentially increasing risk of falls, injury and/or undue fatigue.<ref>Eng JJ. Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) program for stroke. Topics in geriatric rehabilitation. 2010;26(4):310</ref> | ||

* Encourage frequent rest breaks or reduce exercise intensity to decrease fatigue . | * Encourage frequent rest breaks or reduce exercise intensity to decrease fatigue. | ||

* Be mindful of use of compensatory strategies (drop foot, knee hyperextension, circumduction . | * Be mindful of use of compensatory strategies (drop foot, knee hyperextension, circumduction. | ||

* Cue patients to be aware of neglected side, adjust movements and integrate exercises at midline for patients with neglect. | * Cue patients to be aware of neglected side, adjust movements and integrate exercises at midline for patients with neglect. | ||

* Encourage bilateral movements with safe mechanics if patient has a painful shoulder. (e.g. during arm raises, hold on to paretic arm, avoid pulling on paretic arm) . | * Encourage bilateral movements with safe mechanics if the patient has a painful shoulder. (e.g. during arm raises, hold on to paretic arm, avoid pulling on paretic arm). | ||

* Keep arm movements at or below shoulder level if the arm that is most affected by the stroke is weak and has decreased ROM. Arm movements above shoulder height can cause shoulder impingement and other injuries. | * Keep arm movements at or below shoulder level if the arm that is most affected by the stroke is weak and has decreased ROM. Arm movements above shoulder height can cause shoulder impingement and other injuries. | ||

* Incorporate task related activities such as sit to stand, heel raises, step-ups, squats, and lunges. | * Incorporate task related activities such as sit to stand, heel raises, step-ups, squats, and lunges. | ||

* Avoid exercises that overload the joints or increase risk of falling. Begin each exercise in a stable position . | * Avoid exercises that overload the joints or increase risk of falling. Begin each exercise in a stable position. | ||

* Instruct the patient to avoid holding their breath during strength training because this can cause large fluctuations in blood pressure. | * Instruct the patient to avoid holding their breath during strength training because this can cause large fluctuations in blood pressure. | ||

==== 4-Parkinson's Disease ==== | ==== 4-Parkinson's Disease ==== | ||

'''Parkinson's Key Points''' | '''Parkinson's Key Points''': | ||

* Choose the time of day for exercise that is best for the patient. It may be more effective to time exercises with medications. If fatigue is an issue, instruct the patient to try exercising first thing in the morning. | * Choose the time of day for exercise that is best for the patient. It may be more effective to time exercises with medications. If fatigue is an issue, instruct the patient to try exercising first thing in the morning.<ref name=":11">Parkinson Canada. [https://www.parkinson.ca/wp-content/uploads/Exercises_for_people_with_Parkinsons.pdf Exercises for People with Parkinson's. Available from https://www.parkinson.ca/wp-content/uploads/Exercises_for_people_with_Parkinsons.pdf]. [Accessed 21 March 2022]</ref> | ||

* Patients may enjoy doing the exercises to music. | * Patients may enjoy doing the exercises to music.<ref name=":11" /> | ||

* Consider exercising with supervision for those at risk of falls or who have had a recent change in medications (e.g. Levodopa/Carbidopa may produce exercise bradycardia). | * Consider exercising with supervision for those at risk of falls or who have had a recent change in medications (e.g. Levodopa/Carbidopa may produce exercise bradycardia).<ref>Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, Magal M, American College of Sports Medicine, editors. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Wolters Kluwer; 2018. | ||

BibTeXEndNoteRefManRefWorks</ref> | |||

* If the patient is at risk of falling or freezing (becoming rigid) , instruct them to hold on to a chair when performing standing exercises or do chair-based exercises instead. | * If the patient is at risk of falling or freezing (becoming rigid) , instruct them to hold on to a chair when performing standing exercises or do chair-based exercises instead. | ||

Revision as of 15:47, 21 March 2022

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (21/03/2022)

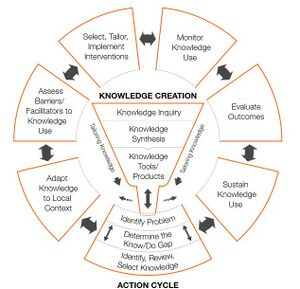

Introduction[edit | edit source]

RExI is an abbreviation for the PT Knowledge Broker facilitated project started in April 2019: Resisted Exercise Initiative (RExI) – Use of resisted exercise by physiotherapists for elderly patients in British Colombia (BC) Hospitals.

The current volume and level of acuity of elderly patients in acute care settings challenges physical therapists to address all needs. One related aspect of practice that is receiving increasing attention is the optimal prescription of resistance exercise in these settings.

Goal: To support best practice in use of resisted exercise by physical therapists for elderly patients in BC Hospitals.

Objectives:

- To determine existing practice.

- To identify opportunities to support enhanced practice.

- To undertake knowledge translation (KT) strategies to target barriers to enhance using of resisted exercise.

- To evaluate effect of introduction of the KT strategies.

This project will:

- Describe current practice to confirm whether there is ‘a gap’ between current actual and desired evidence-based practice for PTs in BC.

- Determine the barriers to desired evidence-based practice from the perspective of the front-line public-practice PT.

- Map the barriers identified to categories identified by KT/implementation/behaviour change science.

- Using KT/implementation/behaviour change science and resources to identify targeted KT strategies to address the barriers.

- Develop/undertake, disseminate & support implementation of the targeted strategies.

- Re-evaluate practice post-implementation of the strategies.

Resistance Exercise Tool Kit[edit | edit source]

Definition and Benefits[edit | edit source]

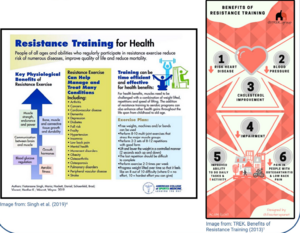

Resistance Exercise is defined as movement using body weight or external resistance that improves muscular strength, power, endurance and it may positively impact mobility, function and independence.[1]

Benefits of resistance exercise ;[2][3]

- Improves muscle strength and tone

- Maintain flexibility and balance

- Weight management and increased muscle to fat ratio

- May help to prevent or reduce cognitive decline in older people.

- Greater stamina (people will not tire easily due to improved body strength)

- Prevention or control of chronic conditions eg (back pain, heart disease, arthritis, obesity &depression)

- Pain management

- Improves posture and decreases the risk of injury

- Increases bone density

- Decreases risk of osteoporosis

- Improves sense of wellbeing, boost confidence and self-esteem

A statement from National Strength and Conditioning Association highlighted the benefits of resistance exercise to older people (Fragala et al .2019).[4]

A properly designed resistance training programme can help in :[5]

- Counteracting the age related changes in human skeletal muscle.

- Enhance the muscular strength ,power and neuromuscular functioning of older adults.

- Improve older adults resistance to injuries and catastrophic events like falls.

- Improve mobility , physical functioning , performance of daily activities (ADL) and preserve independence.

- Help in promoting psychosocial well-being of older adults.

Also Fragala et al .2019 recommended the resisted exercise training programme should be matched appropriately to the individual's abilities and goals.

Considerations and Flags[edit | edit source]

Prior to beginning exercise, liaise with the patient's physician regarding your treatment plan, and discuss any signs or symptoms to monitor. Use your clinical judgement with each patient :[6][7][8]You can also refer to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) screening guidelines flow chart to determine if RExI is appropriate treatment for your patient.

Relative Contraindications[edit | edit source]

If a patient has any of the following caution should be used when considering including resistance exercises in your treatment plan.

Absolute Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Patients with the following conditions should not exercise until their condition is stable or controlled.

Exercise Physiology Foundation[edit | edit source]

1-Muscle strength & life course[edit | edit source]

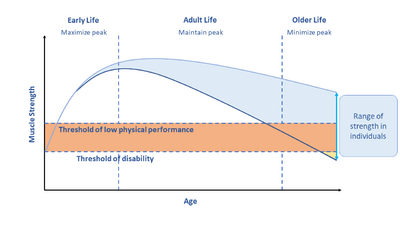

Muscle strength decrease through adult years and life course . There is a strong link between decreased muscle strength and falls, immobility and mortality [4] .

Loss in strength can be moderated by maximizing muscle in early adulthood , maintaining strength in middle age and minimizing loss in older age. This can be achieved through resistance exercise training.[4] [9] *(diagram)

Hospitalized older adults may experience some problems from immobility like: muscle atrophy, sarcopenia[9], cachexia.....eg

1- Muscle Atrophy[edit | edit source]

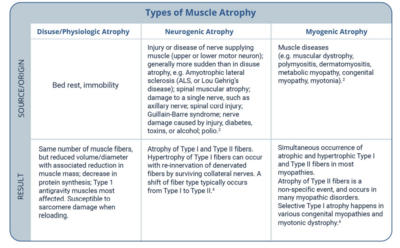

Types of muscle atrophy[10][11]

- Disuse or physiologic Atrophy

- Neurogenic Atrophy[12]

- Myogenic Atrophy

2- Sarcopenia[edit | edit source]

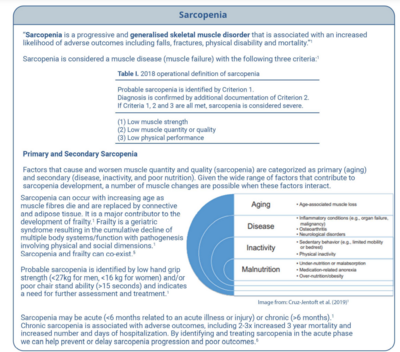

Sarcopenia is defined as a progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder that is associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes like falls, fractures, physical disability and mortality.[9] Sarcopenia is considered a muscle disease ( muscle failure ) with the following 3 criteria:

- Low muscle strength

- Low muscle quantity and quality

- Low physical performance

- Probable sarcopenia is identified by criteria 1

- Diagnosis is confirmed by additional documentation of criteria 2

- Sarcopenia is considered severe if 1,2 &3 criteria are met

3- Cachexia[edit | edit source]

Cachexia is a complex metabolic syndrome associated with underlying illness and characterized by loss of muscle with or without loss of fat mass. The prominent clinical feature of cachexia is weight loss in adults (corrected for fluid retention) or growth failure in children (excluding endocrine disorders). Anorexia, inflammation, insulin resistance, and increased muscle protein breakdown are frequently associated with cachexia. Cachexia is distinct from starvation, age-related loss of muscle mass, primary depression, malabsorption, and hyperthyroidism and is associated with increased morbidity.Sarcopenia is one of the factors that may cause cachexia.[13][14]

2-Regeneration Of Injured Skeletal Muscle[edit | edit source]

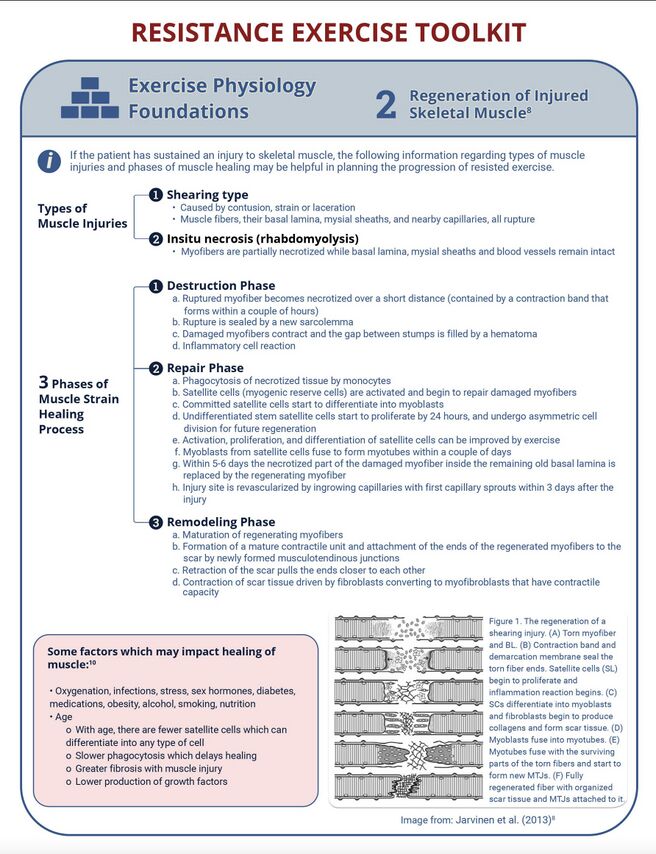

If the patient has sustained an injury to skeletal muscle, the following information regarding types of muscle injuries and phases of muscle healing may be helpful in planning the progression of resisted exercise.[15]

3- Principles Of Strength and Conditioning[edit | edit source]

For further information you can access strength and conditioning page

The Effects of Resistance Exercise on Muscle[edit | edit source]

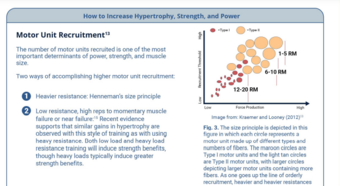

Key terms[16]

- Strength The ability to produce force

- Power The ability to produce force at a high speed of movement (force x distance/time)

- Motor Unit[16] Consists of an alpha motor neuron and the muscle fibres innervated by it

Type I muscle fibres are considered slower but more fatigue-resistant fibres (e.g. beneficial for long distance runners).

Type II fibres are considered the faster, more powerful fibres, but are also more susceptible to fatigue (e.g. more beneficial for sprinters and lifters)

- Henneman's Size Principle[20]

As levels of activation increase (either through increased load or speed), larger motor units are recruited (i.e. Type I, Type IIa, and Type IIb in succession).

4- Prescription Principles (Older Adults)[edit | edit source]

- Assessment

- Screen for contraindications

- Resistance exercise has been shown to be safe in the frail, elderly population, but if you have any questions or are unsure of medical stability for resistance exercises, check with the primary care provider, or use https://eparmedx.com/.

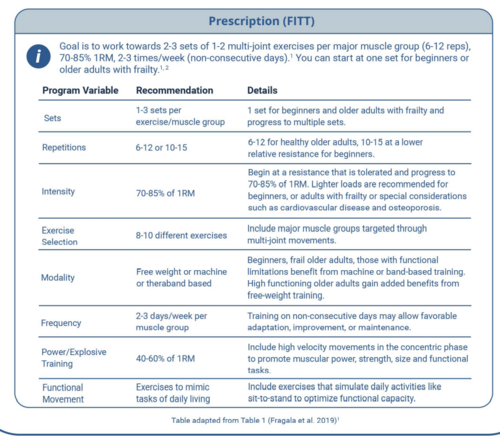

- Prescription (FITT)

Goal is to work towards 2-3 sets of 1-2 multi-joint exercises per major muscle group (6-12 reps), 70-85% 1RM, 2-3 times/week (non-consecutive days). You can start at one set for beginners or older adults with frailty.[4][1]

Appropriate Intensity[edit | edit source]

- Free weights, machines, or bands or body weight can be used. Beginners, frail older adults, or those with functional limitations, benefit from machine-based resistance training, training with resistance bands and isometric training to help simplify and/or stabilize movements. High functioning older adults gain added benefit from free-weight resistance training as these exercises may engage additional muscles for support and stability and are more similar to movements used in activities of daily living [4][21]

- Lift and lower the weight in a controlled manner with a focus on good form[22]

- Rest 1.5-3 min between sets. The greater the intensity, the longer rest period is needed. The rest allows the muscles energy stores to be restored and therefore you can maximize the intensity of each set. Exercises done with the muscles in a fatigued state can lead to poor form and injury[4][23]

- Primary attention should be given to lower body exercises as age-related reductions are more pronounced in the lower body[21]

- In general, larger muscle groups should be worked before smaller muscle groups and multi-joint exercises (encouraged) should be done before uni-joint[4]

Muscle Groups[edit | edit source]

The specific muscle groups targeted can be based on manual muscle testing, dynamometer testing, or functional muscle testing.Exercise selection should include major muscle groups targeted through multi-joint movements. Some examples of exercises that may be included in a whole-body resistance exercise session for general weakness or prevention of decline/deconditioning (if there is not a targeted area of weakness) include:

(see standardized exercise programs for more specifics)

Basic

- Squat (leg press if unable to do squat)

- Knee extension

- Knee flexion (leg curl or Romanian deadlift; deadlift with caution in elderly patients with spine issues)

- Chest press

- Seated low row

Complementary

- Hip adduction/abduction

- Hip flexion/extension

- Calf raise (standing or seated)

- Elbow flexion/extension

- Core/abdominals

One multi-joint exercise should be prescribed for major muscle groups although lower limbs may respond better to exercise.

Monitoring and progression[edit | edit source]

Progression should follow general exercise principles of individualization, periodization, and progression.[1][24][25][21]

For progression of intensity, continue to use the method utilized for your initial strength testing prescription.

Progression[edit | edit source]

The following summarizes simple progression recommendations:

- Volume - manipulate sets, reps, weight

- Equipment - Body weight, bands, machine, free weight

- Stability - Lying, seated, kneeling, standing both feet on flat surface, standing single leg on flat surface, standing both legs on unstable surface, standing single leg on unstable surface

- Complexity - Single joint + single exercise, multi-joint + single exercise, combined exercises

It is important to explain to patients that, with resistance training, they should expect some delayed onset muscle soreness.

For patients with medical issues, continue to monitor as per clinical judgement (e.g. SpO2 with patients with COPD; Borg for patients who are short of breath; heart rate for patients with a cardiac condition; or blood sugar for patients with diabetes

Additional Notes[edit | edit source]

Where possible, resistance exercise should be prescribed in combination with aerobic training because both types of exercise elicit distinct benefits.To optimize functional capacity, resistance training programs should include familiarization to training in which the patient's body mass is used for resistance and in which daily activities are simulated (like sit-to-stand).[26] High speed motion (at low to moderate intensity 30-60% 1 RM) can also be incorporated to promote greater improvements in the functional task performance of older adults. For more information about resistance training in the frail older adult, see the "Special Population " section on frailty.

Grip strength is a robust proxy indicator of overall strength. Grip strength of <26kg in men and <16 kg in women have been established as a biomarker of age related disability and early mortality and have been strongly related to incident mobility limitations and mortality.

Simple Progression Recommendations

Volume: Manipulate sets, reps, weight

Equipment: Body weight, bands, machine, free weight

Stability: Lying, seated, kneeling, standing both feet on flat surface, standing single leg on flat surface, standing both legs on unstable surface, standing single leg on unstable surface[27].

Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Supporting Your Patient to Participate in Strength Training.[28]

A well-supported behaviour change strategy to develop SMART goals and a plan that your client is confident that they can do:

Special Population[edit | edit source]

1-COPD[edit | edit source]

COPD Key Points[29]

- Performing pursed lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing can increase breathing efficiency .[30]

- Increasing oxygen therapy during exercise may help to prevent exercise-induced hypoxemia.

- Instruct the patient to avoid extreme weather conditions and schedule exercise sessions during mid-late morning hours.

- Exercise frequency, duration, intensity as well as a list of exercises are included in the document AECOPD-Mob: Clinical Decision-Making Tool for Safe and Effective Mobilization of Hospitalized Patients with AECOPD.

2-Cardiac[edit | edit source]

Cardiac Key Points:[30]

- Patients with left ventricular outflow, decompensated chronic heart failure or unstable dysrhythmias should not exercise.

- Patients with significant aortic stenosis should avoid strength training.

- Patients who have had a myocardial infarction should closely monitor intensity level and stay within the patient's recommended exercise heart rate range.

- Patients with congestive heart failure should closely monitor the intensity level and adjust workout if feeling fatigued. Instruct patient to stop exercising if they experience chest pain/angina.

- Patients with atrial fibrillation should adjust how hard and how long exercises are performed based on how they feel.

- Exercise should be performed without Valsalva maneuver (i.e. exhaling against a closed glottis).

- Instruct the patient to stop exercising immediately if experiencing angina.

- Upper body exercises may precipitate angina more readily than lower body exercises because of a higher pressor response.

- An extended warm up and cool down may reduce the risk of angina or other cardiovascular complications following exercise.

- If nitroglycerin has been prescribed, instruct the patient to carry it when exercising.

- Instruct the patient to avoid exercising in extreme weather conditions.

3-Stroke[edit | edit source]

- Add task-oriented circuit training to improve transfer skills, mobility and ADLs/functional tasks.

- Avoid putting the most challenging or complex exercises at the end of an exercise program as the patient might be tired-potentially increasing risk of falls, injury and/or undue fatigue.[32]

- Encourage frequent rest breaks or reduce exercise intensity to decrease fatigue.

- Be mindful of use of compensatory strategies (drop foot, knee hyperextension, circumduction.

- Cue patients to be aware of neglected side, adjust movements and integrate exercises at midline for patients with neglect.

- Encourage bilateral movements with safe mechanics if the patient has a painful shoulder. (e.g. during arm raises, hold on to paretic arm, avoid pulling on paretic arm).

- Keep arm movements at or below shoulder level if the arm that is most affected by the stroke is weak and has decreased ROM. Arm movements above shoulder height can cause shoulder impingement and other injuries.

- Incorporate task related activities such as sit to stand, heel raises, step-ups, squats, and lunges.

- Avoid exercises that overload the joints or increase risk of falling. Begin each exercise in a stable position.

- Instruct the patient to avoid holding their breath during strength training because this can cause large fluctuations in blood pressure.

4-Parkinson's Disease[edit | edit source]

Parkinson's Key Points:

- Choose the time of day for exercise that is best for the patient. It may be more effective to time exercises with medications. If fatigue is an issue, instruct the patient to try exercising first thing in the morning.[33]

- Patients may enjoy doing the exercises to music.[33]

- Consider exercising with supervision for those at risk of falls or who have had a recent change in medications (e.g. Levodopa/Carbidopa may produce exercise bradycardia).[34]

- If the patient is at risk of falling or freezing (becoming rigid) , instruct them to hold on to a chair when performing standing exercises or do chair-based exercises instead.

5-Multiple Sclerosis (MS)[edit | edit source]

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Key Points:

- As MS patients lack endurance, increase the number of repetitions rather than the weight or resistance to help improve endurance.

- Instruct patients to avoid exercising in high temperatures and during the hottest part of the day.

- Encourage the patient to drink cool fluids before, during and after your exercise session.

- Avoid exercises/activities that may increase risk of falling.

- Set reasonable expectations for progression; i.e. some patients may not see improvements in strength over time depending on their disease progression, but resistance exercise is still beneficial in prevention of deterioration.

6- Spinal Cord Injury[edit | edit source]

Spinal Cord Injury Key Points:

- An individual with a SCI should do at least 20 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity plus 3 sets of strength training exercises for each major functional muscle group at a moderate to vigorous intensity, 2x/week to reach a minimum threshold for improving cardiorespiratory health (cardiorespiratory fitness).

- Patients with cervical or high thoracic injury (i.e. T6 and above) should be aware of the symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia before beginning.15 If a patient is experiencing autonomic dysreflexia, keep them sitting upright, address the suspected cause (e.g. full bladder, kinked catheter, or other stimulus below the level of injury) . If symptoms persist, seek medical attention.

7-Arthritis[edit | edit source]

A- Osteoarthritis

- Combining exercise to increase to strength , flexibility ,and aerobic capacity is the most effective management of lower limb osteoarthritis .

- Proper alignment is essential during loading with osteoarthritis of lower limb.

B- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Schedule exercise each day when pain is lowest and pain medication is most effective medication.

- Continue being physical active during flare and inflammation period, but avoid vigorous exercise and repetitive activities .

- Instruct patient to avoid over streteching.

8- Chronic Pain[edit | edit source]

- Gentle exercise help distract patients from pain.

- Advice patients to be persistent and patient.

9-Osteoporosis[edit | edit source]

- Resistance training machines should be avoided.

- Avoid unstable surfaces.

- Begin at lower intensity , exert effort to prevent falls.

- Strength and resistance exercise are recommended ( weight bearing aerobic exercises & multicomponent exercise ).

- Advice patient to form good alignment over intenesity.

10- Diabetes[edit | edit source]

- Instruct patient to drink a plenty of exercise.

- Always watch signs of low blood sugar.

- Instruct patient to always check with their physician if they felt signs of low blood sugar.

11- Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Instruct patient to start with short periods of exercise.[2][38][39]

- Encourage patients to be as active as best as they can.

- Always ask patients to listen to their bodies.

12- Frailty[edit | edit source]

- Avoid exercises that over-load joints and can led to falling. [30]

- Be alert to signs of dehydration and insulin insensitivity as these patient are susceptible to these conditions.[36]

- Patients with frailty can follow the general guides of resistance exercises but they should mind the intensity to be at lower level.

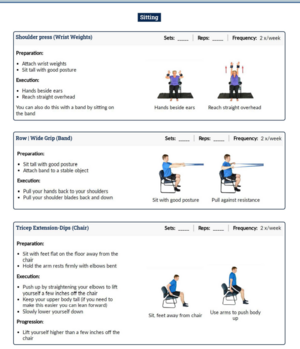

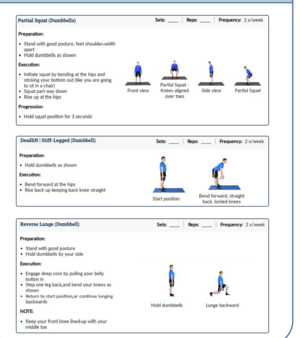

Standardized Exercise Programme[edit | edit source]

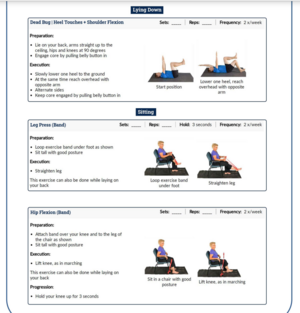

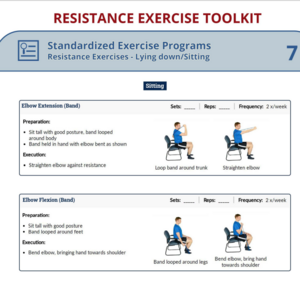

Resistance Exercise ( Lying down / Sitting )[edit | edit source]

Resistance Exercise (Standing position )[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Loveless MS, Ihm JM. Resistance exercise: how much is enough?. Current sports medicine reports. 2015 May 1;14(3):221-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Exercise prescription principles - Exercise.trekeducation.org https://exercise.trekeducation.org/2021

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association | Choosing Wisely Choosing Wisely | Promoting conversations between providers and patients https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-physical-therapy-association/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, Izquierdo M, Kraemer WJ, Peterson MD, Ryan ED. Resistance training for older adults: position statement from the national strength and conditioning association. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2019 Aug 1;33(8).

- ↑ Ratamess N. ACSM's foundations of strength training and conditioning. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021 Mar 15.

- ↑ Kim J, Fanola C, Ouzounian M, Hughes GC, Pyeritz RE, Gleason TG, Evangelista-Masip A, Braverman AC, Montgomery DG, Ehrlich M, Schermerhorn M. ACUTE AORTIC DISSECTION IN PATIENTS WITH MITRAL VALVE DISEASE. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020 Mar 24;75(11_Supplement_1):2255-.

- ↑ Jeevanantham D, Rajendran V, McGillis Z, Tremblay L, Larivière C, Knight A. Mobilization and exercise intervention for patients with multiple myeloma: clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the Canadian Physiotherapy Association. Physical therapy. 2021 Jan;101(1):pzaa180.

- ↑ Stiller K, Phillips A. Safety aspects of mobilising acutely ill inpatients. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2003 Jan 1;19(4):239-57.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel JP, Rolland Y, Schneider SM, Topinková E. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older PeopleA. J. Cruz-Gentoft et al. Age and ageing. 2010 Jul 1;39(4):412-23.

- ↑ He N, Ye H. Exercise and muscle atrophy. Physical Exercise for Human Health. 2020:255-67.

- ↑ Ding S, Dai Q, Huang H, Xu Y, Zhong C. An overview of muscle atrophy. Muscle Atrophy. 2018:3-19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dumitru A, Radu BM, Radu M, Cretoiu SM. Muscle changes during atrophy. Muscle Atrophy. 2018:73-92.

- ↑ Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argilés J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, Jatoi A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lochs H, Mantovani G, Marks D. Cachexia: a new definition. Clinical nutrition. 2008 Dec 1;27(6):793-9.

- ↑ Ding S, Dai Q, Huang H, Xu Y, Zhong C. An overview of muscle atrophy. Muscle Atrophy. 2018:3-19.

- ↑ Järvinen TA, Järvinen M, Kalimo H. Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2013 Oct;3(4):337.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Kraemer WJ, Looney DP. Underlying mechanisms and physiology of muscular power. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2012 Dec 1;34(6):13-9.

- ↑ Phillips SM. A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy. Sports Medicine. 2014 May;44(1):71-7.

- ↑ Khan KM, Scott A. Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists’ prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair. British journal of sports medicine. 2009 Apr 1;43(4):247-52.

- ↑ Deschenes MR. Effects of aging on muscle fibre type and size. Sports medicine. 2004 Oct;34(12):809-24.

- ↑ Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low-vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2017 Dec 1;31(12):3508-23.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Ribeiro AS, Nunes JP, Schoenfeld BJ. Selection of resistance exercises for older individuals: The forgotten variable. Sports Medicine. 2020 Jun;50(6):1051-7.

- ↑ Fiataraone Singh M, Hackett D, Schoenfeld B, Vincent HK, Wescott W. ACSM Guidelines for Strength Training: Resistance Training for Health. AC o. S. Medicine (Ed.). 2019.

- ↑ Scudese E, Willardson JM, Simão R, Senna G, de Salles BF, Miranda H. The effect of rest interval length on repetition consistency and perceived exertion during near maximal loaded bench press sets. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015 Nov 1;29(11):3079-83.

- ↑ Cheung K, Hume PA, Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness. Sports medicine. 2003 Feb;33(2):145-64.

- ↑ Tomasone JR, Flood SM, Latimer-Cheung AE, Faulkner G, Duggan M, Jones R, Lane KN, Bevington F, Carrier J, Dolf M, Doucette K. Knowledge translation of the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults aged 18–64 years and Adults aged 65 years or older: a collaborative movement guideline knowledge translation process. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2020;45(10):S103-24.

- ↑ Alley DE, Shardell MD, Peters KW, McLean RR, Dam TT, Kenny AM, Fragala MS, Harris TB, Kiel DP, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Grip strength cutpoints for the identification of clinically relevant weakness. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014 May 1;69(5):559-66.

- ↑ McLean RR, Shardell MD, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, Fragala MS, Harris TB, Kenny AM, Peters KW, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Kritchevsky SB. Criteria for clinically relevant weakness and low lean mass and their longitudinal association with incident mobility impairment and mortality: the foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) sarcopenia project. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014 May 1;69(5):576-83.

- ↑ AuYoung M, Linke SE, Pagoto S, Buman MP, Craft LL, Richardson CR, Hutber A, Marcus BH, Estabrooks P, Gorin SS. Integrating physical activity in primary care practice. The American journal of medicine. 2016 Oct 1;129(10):1022-9.

- ↑ Camp PG, Reid WD, Chung F, Kirkham A, Brooks D, Goodridge D, Marciniuk DD, Hoens AM. Clinical decision-making tool for safe and effective prescription of exercise in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from an interdisciplinary Delphi survey and focus groups. Physical therapy. 2015 Oct 1;95(10):1387-96.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Thompson WR, Sallis R, Joy E, Jaworski CA, Stuhr RM, Trilk JL. Exercise is medicine. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2020 Sep;14(5):511-23.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827620912192

- ↑ Brown G, Brunton K, French E, Gilmore P, Gregor T, Howe JA, Kelloway L, Levy J, Matthews J, McCullough C, McNorgan C. Post Stroke Community-Based Exercise Guidelines. InINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF STROKE 2016 Sep 1 (Vol. 11, pp. 64-64). 1 OLIVERS YARD, 55 CITY ROAD, LONDON EC1Y 1SP, ENGLAND: SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD.

- ↑ Eng JJ. Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) program for stroke. Topics in geriatric rehabilitation. 2010;26(4):310

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Parkinson Canada. Exercises for People with Parkinson's. Available from https://www.parkinson.ca/wp-content/uploads/Exercises_for_people_with_Parkinsons.pdf. [Accessed 21 March 2022]

- ↑ Riebe D, Ehrman JK, Liguori G, Magal M, American College of Sports Medicine, editors. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Wolters Kluwer; 2018. BibTeXEndNoteRefManRefWorks

- ↑ Tips for Exercising Safely When You Have Diabetes | HealthLink BC https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/illnesses-conditions/diabetes/tips-exercising-safely-when-you-have-diabetes Sep 23, 2021

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Symptoms of Low Blood Sugar | HealthLink BC https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/illnesses-conditions/diabetes/symptoms-low-blood-sugar

- ↑ Carbohydrate Foods | HealthLink BC https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/healthy-eating-physical-activity/food-and-nutrition/nutrients/carbohydrate-foods

- ↑ Jeevanantham D, Rajendran V, McGillis Z, Tremblay L, Larivière C, Knight A. Mobilization and exercise intervention for patients with multiple myeloma: clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the Canadian Physiotherapy Association. Physical therapy. 2021 Jan;101(1):pzaa180

- ↑ Understanding How Bone Cancer Is Staged and Graded | CTCA https://www.cancercenter.com/cancer-types/bone-cancer/stages Sep 21, 2021

![[The University of British Columbia Physical Therapy Knowledge Broker Information Page https://physicaltherapy.med.ubc.ca/physical-therapy-knowledge-broker/resisted-exercise-initiative-rexi-2/]](/images/thumb/3/32/RExI_Considerations_and_Flags.jpg/508px-RExI_Considerations_and_Flags.jpg)