Sternoclavicular Joint Disorders: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 307: | Line 307: | ||

'''Anterior Scalene MET:''' | '''Anterior Scalene MET:''' | ||

Patient seated with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/ | Patient seated with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/chair and looking towards the affected shoulder. Ask the patient side-flex their head away then take a deep breath in. Hold the breath then exhale it out as they get a little more movement in the side flexion. Repeat three or four times and ask the patient to do this regularly at home. | ||

Middle Scaleni | Middle Scaleni can be another cause of rib elevation. It inserts into the first rib and is the largest of the three Scaleni. | ||

Posterior Scaleni is attached at the back to the second rib and originates from the transverse processes of the lowest six cervical vertebrae. | |||

Patient seated with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/chair. Ask the patient side-flex their head away then take a deep breath in. Hold the breath then exhale it out as they get a little more movement in the side flexion. Repeat three or four times and ask the patient to do this regularly at home. | |||

Scalene cramp test | |||

Another test that can be useful in assessing scalene. Ask your patient to rotate their head and then side-flex by getting their chin down into that supraclavicular fossa on the side that you want to test. Waiting to see if they start to get local or referred pain and see if they hold that position for 30 seconds. The test is positive if the patient gets cramp. | |||

Scalene release test | |||

Patient seated with their hand on their forehead, then they elevate their elbow above their head. This movement should open up a space for the Brachial plexus and the Scaleni and reduce their symptoms. | |||

== Differential Diagnosis<ref name="Higginbotham" /><ref name="Bontempo" /><ref name="Gaunt">Gaunt BW, Boers, T. SC, AC, & spinal specific manual techniques can dramatically increase shoulder girdle elevation. Presented at: Combined Sections Meeting; Feb 10, 2011; New Orleans, LA.</ref> == | == Differential Diagnosis<ref name="Higginbotham" /><ref name="Bontempo" /><ref name="Gaunt">Gaunt BW, Boers, T. SC, AC, & spinal specific manual techniques can dramatically increase shoulder girdle elevation. Presented at: Combined Sections Meeting; Feb 10, 2011; New Orleans, LA.</ref> == | ||

Revision as of 17:41, 24 July 2020

Original Editor - Ashley Plawa and Joseph So as part of the Temple University EBP Project

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Joseph So, Admin, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Ashley Plawa, Tony Lowe, 127.0.0.1, Scott A Burns, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tim Hendrikx, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell and Robin Tacchetti

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

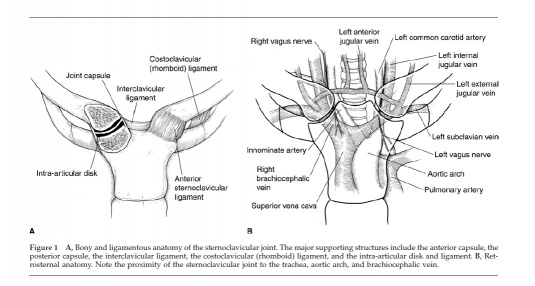

The Sternoclavicular (SC) joint is the only bony joint that connects the axial and appendicular skeletons. The SC joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation of the sternum and the clavicle. Due to the joint’s articulation between the medial clavicle and the manubrium of the sternum and first costal cartilage, the joint has little bony stability. Between the medial clavicle and the manubrium is a dense fibrocartilaginous disc that separates the joints into two distinct synovial compartments.

The intra-articular ligament provides joint stability and prevents medial displacement of the clavicle. This ligament originates from the junction of the first rib and sternum and passes through the SC joint and attaches to the clavicle on the superior and posterior side. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments restrain anterior and posterior translation of the medial clavicle. The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments originate on the anterior and posterior ends of the clavicle, respectively, and insert onto the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium, respectively. The SC joint is supported superiorly by the interclavicular ligament that connects the superomedial portions of each clavicle.

The blood supply to the SC joint is from the articular branches of the internal thoracic and suprascapular arteries.

The SC joint is innervated by the branches of the medial suprascapular nerve. The brachiocephalic trunk, common carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein all lie directly posterior to the SC joint[1].

Figure adapted from: Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Patients with SC joint dysfunction can be classified into two categories based of the mechanism of injury: traumatic or atraumatic.

Traumatic

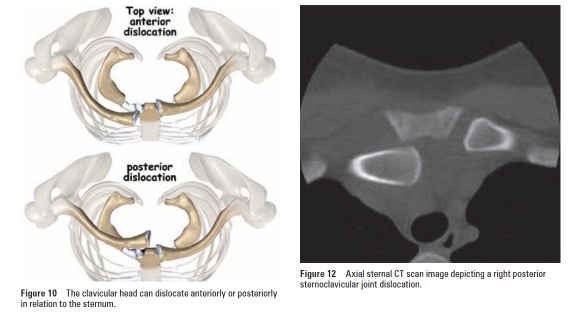

Traumatic injuries to the SC joint range from minor subluxation to complete dislocations. Injuries to the SC joint are rare and infrequently seen in physical therapy. Full dislocation of the SC joint is rare due to the large amount of force and specific vector required to displace the joint. Typically, traumatic injuries to the SC joint occur during: falls, sports-related injuries or vehicular accidents. Anterior SC joint dislocations are more common[3][4]. Posterior dislocations have serious clinical implications as the surrounding nerves and vessels may be compromised[5].

A direct trauma by falling laterally to the shoulder, with the force transmitting naturally from the clavicle to the SC joint, can cause either anterior or posterior direct force on the SC joint depending on the arm position[6].

Atraumatic

The SC joint is vulnerable to the same disease processes than occur in joints such as degenerative arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, infections, and spontaneous subluxation of the joint. A thorough history is required to determine the presence of non-musculoskeletal disorders[1].

Sternoclavicular joint disorder can result from abnormal motion of the scapulothoracic joint and abnormal scapular motion[6].

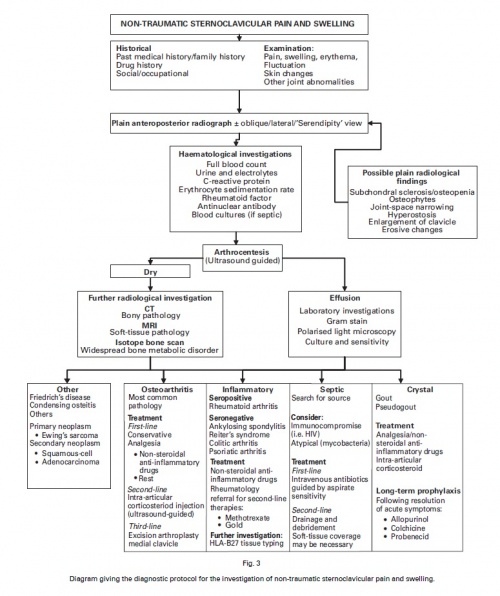

Non-traumatic SC joint pain and swelling might be caused by[6]:

- Osteoarthritis most common pathology

- Inflammatory:

- Seropositive: such as Reactive arthritis (developing response to infections in other parts of the body)

- Seronegative: such as Ankylosing Spondylitis, Reiter's syndrome, Psoriatic Arthritis

- Septic

- Crystal: Gout and Psudogout

- Other:Freidrick's disease, Condensing Osteitis (a benign disorder characterized by sclerosis of the clavicle, but it doesn't affect the SC joint itself), SAPHO (which describes a group of symptoms which are synovitis, acne, pustulosis- an inflammatory skin condition characterized by blisters on the soles of the feet or on the palms of the hands-, hyperostosis which is excess bone growth, and osteitis, which is bone inflammation), Ewisng sarcoma, Squamous Cell carcinoma/adenocarcinoma[3]

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

The clavicle plays an integral role in maintaining the subacromial space capacity during arm elevation. Posterior rotation of the clavicle results in elevation of its lateral end where it articulates with acromion forming the AC joint. This elevation will raise the acromion, maintaining the subacromial space during arm elevation above the head.

The shape of the clavicle is convex anteriorly at the medial end and concave anteriorly at the lateral end. The medial end articulates with the manubrium, the sternum, and the first rib costocartilage.

Shoulder elevation is associated with we can see that posterior rotation, we can see that elevation of the clavicle.

Protraction and retraction around the shoulder are associated with elevation at the SCJ and tightness of the costoclavicular ligament. Depression causes contact through the SC disc and tightness of the interclavicular ligament. Retraction is limited by the anterior part of the sternoclavicular ligament and some compression through the disc.

Clavicle posterior rotation with shoulder flexion and scaption[7].

Posterior rotation is an important movement of the joint that needs to be assessed. As the range of elevation increases, the posterior rotation increases[8].

With Scaption, at 30 degrees anterior to the coronal plane, there is about 20 degrees of posterior rotation to elevate the lateral end of the clavicle to optimize the space under the acromion, maintinaing that subacromial space.

Scapular motion on the thorax, and this can be offset by movement at the SC joint. So if you've got a little bit of a sloppy AC joint there, we might not get that much, that movement[7]. Posterior clavicle tilting is associated with posterior rotation and elevation. Protraction and retraction of the clavicle should occur with scapula internal and external rotation.

Wish shoulder external rotation, the medial border of the scapula moves towards the chest wall, towards the rib cage with elevation and posterior tilting.

All these movements will have an effect on the acromion and ultimately the subacromial space, the clavicle and the SCJ.

With contraction, there will be a posterior glide of the medial end of the clavicle. And with elevation, an inferior glide of the medial end of the clavicle occurs[8]. With elevation, the clavicle goes into posterior rotation.

Any small proximal movement limitation around the SCJ will cause a bigger limitation of the distal movement[6].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Traumatic

Patients usually present with complaints of pain and swelling. With mild sprains or subluxations, there may be complaints of instability in the joint. Often with dislocations, a palpable and observable step-off deformity at the SC joint may be present. Posterior dislocations may be associated with more significant symptoms such as: a feeling of compression of the trachea or esophagus, complaints of dyspnea, choking, difficulty swallowing, or a tight feeling in the throat. In the most severe cases of posterior dislocation, complete shock or a pneumothorax may occur and if left untreated and can be associated with complications such as thoracic outlet syndrome and vascular compromise[9].

Classification of Types of Injury[3][4]

- Type I injury is associated with mild to moderate pain associated with movement of the upper extremity. Instability is usually absent and the SC joint is tender to palpation and may be slightly swollen.

- Type II injury is associated with partial tears in the supporting ligaments. The joint may sublux when manually stressed but will not dislocate. Patients report more swelling and pain than those with Type I injuries.

- Type III injury results in complete dislocation, either anteriorly or posteriorly, of the SC joint. Patients report severe pain that is aggravated by any movement of the upper extremity. The involved shoulder may be protracted in comparison to the uninvolved side. Patients may also hold the affected arm across the chest in an adducted position and support the involved arm with the contralateral limb.

Atraumatic[1]

- Osteoarthritis (OA) of the SC joint includes: a report of pain and swelling at the SC joint that is aggravated with palpation, ipsilateral shoulder abduction, and/or shoulder flexion about the horizontal. Other findings include: osteophyte prominence at the medial end of the clavicle, creptius, or a fixed subluxation. Degenerative processes of the SC joint become increasingly more common with advanced age. Postmenopausal women are more susceptible than premenopausal women or men.

- Rheumatoid arthritis, RA, of the SC joint includes: a report of swelling of the SC joint, tenderness of the SC joint, crepitus, and painful limited movement of the shoulder. Other findings include synovial inflammation, pannus formation, bony erosion, and degeneration of the intra-articular disc. Isolated joint involvement is rare. It is more common to see multiple joints affected with RA and often is present bilaterally.

- Infection of the SC joint include: report of pain, swelling of the SC joint, tenderness around the SC joint, fever, chills, and/or night sweats. A definitive diagnosis is found with aspiration or open biopsy. Septic arthritis is associated with infection of the SC joint and is seen in patients that have RA, sepsis, infected subclavian central lines, alcoholism, or HIV. It is also seen in immunocompromised patients, renal dialysis patients, and intravenous drug users.

- Spontaneous anterior subluxation includes: patient report of a “pop”, or sudden subluxation of the medial end of the clavicle. It is commonly seen in patients in their teens and twenties who demonstrate ligamentous laxity and may occur with overhead elevation of the arm.

- The clinical presentation of seronegative sponyloarthropathies is similar to that of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, or colitic arthritis. This disorder is characterized by age of onset before 40 years old, inflammation of large peripheral joints, and absence of serum antibodies. Patients present with unilateral involvement, swelling, and tenderness of the SC joint, and pain with full arm abduction.

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis includes soft tissue ossification and hyperostosis, or excessive growth of bone, between the clavicles. A patient with sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis may report localized pain, swelling and warmth over the SC joint. Symptoms are often bilateral and the range of motion of the shoulder can be affected.

- Condensing osteitis includes: patient report of pain and swelling over the affected area. Symptoms are usually unilateral and present in women in their late child bearing years. This condition presents with sclerosis and enlargement of the medial end of the clavicle.

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis) includes: discomfort, swelling, and crepitus of the SC joint in absence of trauma, infection, or other symptoms. The patient reports loss of ipsilateral shoulder range of motion.

The following table summarizes the main differences between the non-traumatic causes of SC disorders[6][3]:

|

Conditions |

Demographics | Clinical/Lab Findings | Radiological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Systematic Arthritis |

|||

|

Osteoarthritis |

>50 YOA |

Normal |

OA Changes |

|

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

Women any age |

?RH +ve | NOrmal/erosion |

|

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies |

Men <40 YOA |

+ve HLA-B27 | Normal/erosion |

|

Crystal Arthropathies |

Men >40 YOA |

Joint fluid, elevated ESR (acute) | Secondary OA changes, soft tissue calcifications |

|

Infective Conditions |

|||

|

Septic Arthritis/Osteomylitis |

Any age |

Systematic Signs +ve Blood tests |

Associated Periosteal Changes |

|

Joint Specific Conditions |

|||

|

SAPHO Syndrome |

Middle aged adults |

Skin changes ESR/CRP mildly elevated |

Erosive changes

Ossification of ligament insertion |

Signs and symptoms of SC disorders[6][10]:

Tenderness to palpation

Local Swelling

Localized elevation with elevation above 100°

Pain with active protraction and retraction

The SC pain will be localized around the joint, but patients might also present with referred neck, shoulder, and/or arm pain.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Plain radiographs are indicated at the initial evaluation for SC joint disorders[1]. Computed Tomography (CT) scans are indicated for disease processes in which there is bony destruction or ossification. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides information of whether there is inflammation, soft tissue masses, or osteonecrosis are present. While a MRI radiograph is very thorough, CT is a preferable imaging modality in acute settings due to speed, availability and ability to discern between soft-tissue and bony injuries, especially in acute scenarios[9]. Laboratory studies may help rule in or rule out a certain diagnosis when inflammatory or infectious disease processes are suspected, such as RA, septic arthritis, or osteomyelitis.

Radiographic evaluation for SC joint dislocations includes standard antero-posterior (AP) radiographs of the chest that may suggest and injury to the SC joint[5]. This may, however, not be the best view for visualization of the joint. The use of the serendipity view radiograph has been shown to be of better diagnostic reliability since it is a bilateral view of the SC joint.

Figures adapted from: Bontempo N, Mazzocca A. Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2010;44:361-369.

Considerations in Dysfunctional SCJ[6]:[edit | edit source]

Articular:

- Hypermobile (lax joint).

- Hypermobile (stiff joint). The SCJ tends to e hypeomobile without trauma

- First Rib Position

Myofascial:

- Subclavius (lack of extensibility)

- Sternocleidomastoid (overactivity/lack of extensibility)

- Scaleni

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

Sternocleidomastoid is attached to the lateral side of the SC by its clavicular head and to the medial side by its sternal head. Postural changes or cervical spine disorders can be transferred to the SC joint via the Sternocleidomastoid muscle through its attachments.

The Subclavius, lies just behind the pectoralis major muscle, originates from the first costochondral junction and inserts in the inferior surface of the lower end of the clavicle tubercle. An active trigger point in this area has a C5/6 referral pattern to the arm [11].

To assess the Subclavius, the patient lies down comfortably on their side and protract their shoulder while maintaining the Pectoralis Major relaxed. You can palpate the Subclavius by moving your fingers from the medial end of the clavicle to the underside of the bone. The muscle is elet at the area between the middle and lateral third. If you palpate underneath this angle you can feel the insertion of Subclavius. Apply some pressure on the insertion and ask the patient how they fee . This can be tricky because the pressure in this area will be uncomfortable anyway so it might be useful to assess the asymptomatic side first then check the painful side and see how your patient feels.

If the patient reports the C5/6 referral on their arm, this indicates an active trigger point which can be treated by Digital Ischemic Compression. Discuss this treatment with your patient and explain to them that it might take some time to release the muscle[6].

Clinical Tip: to make sure you are palpating the Subclavius and not the Pectoralis Major, ask the patient to construct it first then relax it then work on finding the Subclavius[6].

Surface marking palpation:

It is easy to palpate the SC joint by finding the jugular notch then move laterally to palpate the SCJ.

Then sternal angle,, often called the angle of Louis, can be felt at the point where the sternum projects the furthest part forward. This prominent surface mark can be used as a mark of the second rib articulation.

In an optimally positioned shoulder, the scapula is upwardly rotated. The distance between the medial and lateral ends of the clavicle would roughly equal the breadth of two raised fingers. I like to use a two-finger breath rule. You can use this ''rule of finger'' clinically to assess the clavicle posture in relation to the shoulder and scapula[6].

Assessment of joint play and mobility:(compare symptomatic to non-symptomatic side):

Assessment of distraction mobility: patient seated. Stand behind your patient, place one hand fixing the Manubruim and another on the axis of the clavicle. Take a skin slack and apply a slight distraction to feel the movement in the joint.

Assessment of posterior glide: with your patient lying down in supine position, palpate the SCJ. Ask your patient to raise both arms to shoulder height level and actively protract their shoulders. Check if the joint rotates posteriorly during this movement by comparing the movement on both sides.

Assessment of inferior glide: with your patient lying down in supine position, palpate the SCJ. Ask your patient to elevate (shrug) their shoulders and check if the joint glides inferiorly.

Assessment of posterior rotation: this might be a difficult movement to assess. With your patient lying down in supine comfortable, sit behind the patient and glide your fingers underneath the posterosuperior edge. You can assess the movement while the patient fully elevates their arms or moves them into abduction. There should be about 30 ° of rotation in the posterosuperior surface with the shoulder flexion. The ligaments tighten to limit this movement after 45° of posterior rotation, unlike with anterior rotation where the movement is limited after 10% of its ROM[6] increasing the joint compression to protect the joint stability. The costoclavicular ligament is the most important structure in restraining the posterior rotation.

First Rib Assessment:

Elevation compression:

Aim: check if the first rib is elevated

Patient seated comfortably. Stand behind your patient, your hands over the Upper Trapezius just behind the supra clavicular fossa, and then just gently, feel if there is rising of the first rib while the patient takes a deep breath and compare both sides.

Rotation Side flexion:

Ask the patient to rotate their head to the shoulder on one side as far as they can then apply passive flexion to the head and compare the ROM on both sides. Rotation to the right shoulder assesses the first rib elevation on the left side. If the first rib is elevated it will block the spinous process of C7 and that will reduce that range.

A possible cause for elevated rib is Anterior Scalene muscle that inserts into the first rib. The muscle comes from the transverse processes of the third to the sixth cervical vertebrae then it passes onto the Scalene tubercle of the first rib behind the Sternocleidomastoid.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are not any specific outcome measures that specifically look at the SC joint but the following could potentially be used as SC joint injury outcome measures since SC joint injuries typically impact upper extremity function:

- DASH

- QuickDASH

- Penn Shoulder Score

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

The physical examination of a patient with a suspected SC joint injury may include the following:

- Screening of the cervical spine

- Active and passive range of motion of the associated shoulder region, AC, and SC joints

- Observation and palpation of key structures/regions

- Resistive testing of the shoulder region

- Functional testing

Little evidence exists for the optimal management of SC joint dysfunction, but may be impairment and patient-response driven. The physical therapist may consider exercises, manual therapy techniques, education or other treatment interventions based on the observed impairments. Often times, SC dysfunction does not require an extensive course of physical therapy.

Initial physical therapy interventions may include:

- Mobility exercises including AROM, AAROM, PROM of the shoulder

- Resistive strengthening

- Motor control training

- Scapular stabilization

- Manual therapy directed at the SC joint, GH joint, and AC joint

In severe, acute traumatic dislocations, reduction of the joint may be required by the appropriate medical provider. Posterior dislocations of the SC joint should be considered a medical emergency due to the proximity of major arteries, nerves, trachea, esophagus and lungs. Before actual physical therapy is applied, the clavicle should be placed back into the Sternoclavicular joint.[12]

When the patient has an anterior dislocation, most authors recommend at least one closed reduction attempt. This reduction may be performed under local anesthesia, under sedation, or under general anesthesia. Place the patient with his arm supine and with a thick pad between his shoulders. The reduction entails abduction of the shoulder to 90 degrees, 10 to 15 degrees of extension, and traction on the arm with posterior pressure over the sternal end of the clavicle.[12]

When the patient has a posterior dislocation, closed reduction should also be applied under general anesthesia. There are several techniques described, the standard abduction traction technique is similar to the technique used for anterior dislocations. Place the patient with the shoulder of the injury side supine near the edge of the table with a thick pad between the scapulae. Apply lateral traction with the arm in abduction and extension. The clavicle can be grasped with the fingers to dislodge it from behind the sternum, if reduction is not succeeded. If the clavicle is still dislocated, use a towel clip to grasp it and it is lifted back into position. This procedure is always done with sterile technique. When the clavicle is reduced after a posterior dislocation it is usually stable.[12]

Surgical stabilization is not recommended by most authors because of the risks for complications such as infections. This type of stabilization should only be used in patients who have failed conservative treatment.[12]

If the Sternoclavicular joint is unstable, let the patient use a sling for a few weeks until symptoms resolve. This is followed by a progressive program to regain normal range of motion and a progressive strengthening program. This strengthening program focusses on the deltoideus and trapezius since they are dynamic stabilizers. [12]

After reduction, physical therapy for anterior and posterior dislocation is similar. Beginning with immobilization of the shoulder in a position of scapular retraction. This depends on the stability of the joint. If the dislocation is stable, the patient is immobilized in a figure-of-8 dressing sling for 6 weeks.[13],[12]

On the second day allow the patient to perform gentle pendulum exercises but caution him against active flexion or abduction of the shoulder above 90°.[14] [15]

On the 4th day after surgery start gentle physical therapy. This therapy should be focused on passive glenohumeral motion, including internal rotation and external rotation.[16]

If the joint is stable at week 3, start elbow exercises and glenohumeral rotation. These exercices include active flexion, extension, abduction and internal/external rotation as well as static strengthening exercises. To prevent the shoulder from dislocating again a good guideline is to keep the hand in view during the first three weeks.[12]

The first 6 weeks abduction or other significant SC joint motion is not allowed. After 6 weeks institute more aggressive range of motion exercises including overhead activities with slow integration of strengthening maneuvers.[16]

Beginning at 8 to 12 weeks, start a rehabilitation program of stretching and strengthening exercises.[14][15]

Non-operative Management

There is little attention given to the SC joint in the literature in terms of non-operative management

Management of elevated first rib:

Muscle energy technique can be used also for thoracic outlet syndrome. This technique may be uncomfortable for the patient but it's useful. as it may help the referred pain in the arm. The patient sits relaxed and leaning to the affected side. Apply contact with your middle phalanx of the index finger over the flat bony part of the first rib. As the patient goes in side-flexion with their trunk apply side-flexion on the cervical spine as well then push down on their first rib and take up the slack. Then ask the patient to deep a breath and hold it for about five seconds. And they're holding their breath, they're going to push their left ear into my hand at about 25% of their maximum and hold it there and then breathe out. And as they breathe out, we should get a little relaxation of the muscle insertion into the first rib, and feel a little more glide down on their rib. Repeat this for two to three times until you stop feeling any movement of the rib. You can check if this helped or not by comparing the side flexion and rotation and compare it on both sides (refer to the assessment of the first rib above.

Anterior Scalene MET:

Patient seated with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/chair and looking towards the affected shoulder. Ask the patient side-flex their head away then take a deep breath in. Hold the breath then exhale it out as they get a little more movement in the side flexion. Repeat three or four times and ask the patient to do this regularly at home.

Middle Scaleni can be another cause of rib elevation. It inserts into the first rib and is the largest of the three Scaleni.

Posterior Scaleni is attached at the back to the second rib and originates from the transverse processes of the lowest six cervical vertebrae.

Patient seated with their hand hooked on the side of the bed/chair. Ask the patient side-flex their head away then take a deep breath in. Hold the breath then exhale it out as they get a little more movement in the side flexion. Repeat three or four times and ask the patient to do this regularly at home.

Scalene cramp test

Another test that can be useful in assessing scalene. Ask your patient to rotate their head and then side-flex by getting their chin down into that supraclavicular fossa on the side that you want to test. Waiting to see if they start to get local or referred pain and see if they hold that position for 30 seconds. The test is positive if the patient gets cramp.

Scalene release test

Patient seated with their hand on their forehead, then they elevate their elbow above their head. This movement should open up a space for the Brachial plexus and the Scaleni and reduce their symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis[1][5][17][edit | edit source]

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Septic arthritis

- Atraumatic subluxation

- Seronegative sponyloarthropathies

- Crystal deposition disease

- Sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis

- Condensing osteitis

- Friedrich’s disease (aseptic osteonecrosis)

- SC/AC joint dysfunction

- Sternal Fracture

- Clavicular Fracture

- Anterior dislocation of the SC joint

- Posterior dislocation of the SC joint

The figure below depicts a differential diagnosis flowchart for non-traumatic injuries of the SC joint.

Figure adapted from: Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Higginbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005;13:138-145.

- ↑ The Sternoclavicular Joint. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tr3bNRb2Iso [last accessed on: 2020/07/20]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Robinson C, Jenkins P, Markham PBI. Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. June 2008;90-B(6):685-696.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wirth MA, Rockwood CA. Acute and chronic traumatic injuries of the sternoclavicular joint. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1996;4:268-278.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bontempo N, Mazzocca A. Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joint injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2010;44:361-369.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Horsley I. Stenoclavicular Joint Disorder Course. Physioplus 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ludewig PM, Behrens SA, Meyer SM, Spoden SM, Wilson LA. Three-dimensional clavicular motion during arm elevation: reliability and descriptive data. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004 Mar;34(3):140-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ludewig PM, Reynolds JF. The association of scapular kinematics and glenohumeral joint pathologies. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2009 Feb;39(2):90-104.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Groh GI, Wirth MA. Management of traumatic sternoclavicular joint injuries. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. January 2011;19(1):1-7.

- ↑ Van Tongel A, Karelse A, Berghs B, Van Isacker T, De Wilde L. Diagnostic value of active protraction and retraction for sternoclavicular joint pain. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2014 Dec 1;15(1):421.

- ↑ Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 MacDonald, e. a. (2008). Acromioclavicular and Sternoclavicular Joint Injuries. Orthopedic clinics of North America, 535-545.

- ↑ Kisner, e. a. (2002). The Shoulder and Shoulder Girdle. In therapautic exercise, Foundations and Therniques , 319-385.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Groh, e. a. (2011). Treatment of traumatic posterior sternoclavicular dislocations. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 107-113.fckLRLevel of evidence: 4

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rockwood, e. a. (2010). Resection Arthoplasty of the Sternoclavicular Joint. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 387-393.fckLRLevel of evidence: 1b

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Battaglia, e. a. (2005). Interposition Arthroplasty With Bone-Tendon Allograft: A Technique for Treatment of the Unstable Sternoclavicular Joint. J Orthop Trauma, 124-129.fckLRLevel of evidence: 4

- ↑ Gaunt BW, Boers, T. SC, AC, & spinal specific manual techniques can dramatically increase shoulder girdle elevation. Presented at: Combined Sections Meeting; Feb 10, 2011; New Orleans, LA.