Wheelchair Assessment

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Rucha Gadgil, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Amrita Patro

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Assessment is a second wheelchair service step. Information collected from the assessment will help the wheelchair service personnel and wheelchair user to;

- choose the most appropriate wheelchair from those available;

- determine the most appropriate wheelchair components from those available including any possible additional postural support required;

- decide what training or support the wheelchair user family member/caregiver may need to use and maintain their wheelchair.

Assessments should always be carried out in a clean, quiet space, which may be a space within the wheelchair service, at another health care or community facility, or at the user’s home. If it is necessary to check whether a person has a pressure sore, do this in a private space. Respect the dignity and privacy of the wheelchair user irrespective of their age, gender, religion or socioeconomic status. The assessment process should incorporate two parts:

- Assessment Interview

- Physical Assessment

Assessment Interview[edit | edit source]

The first part of the assessment is the assessment interview. During this part of the assessment the wheelchair service personnel gather information about the wheelchair user, which will help to identify the most appropriate wheelchair for the wheelchair user. Even though the assessment interview components at basic and intermediate levels are very similar, more information is gathered at intermediate level about the wheelchair user’s diagnosis and any physical issues.

The assessment interview components at both basic and intermediate level include information about the wheelchair user, their physical condition, their lifestyle and environment and also examines their existing wheelchair, if applicable.

Even though the assessment interview components at basic and intermediate levels are very similar, more information is gathered at intermediate level about the wheelchair user’s diagnosis and any physical issues in order to determine the requirements for additional postural support devices..

Information about the Wheelchair User[edit | edit source]

The ‘information about the wheelchair user’ part of the wheelchair assessment form has an administrative purpose and ensures that the wheelchair service has the wheelchair user’s basic personal and contact information so that the wheelchair user can be contacted for the follow up in the future. They also give statistical information about the users seen by the service. Goals for the individual is vital to understand what the wheelchair user expects from their wheelchair.

Wheelchair service personnel should also record here what the wheelchair user’s goals are for a new or improved wheelchair. The word ‘goal’ may not be familiar to a wheelchair user. It is up to the wheelchair service personnel to ask questions to find out what the wheelchair user’s goal or goals are.

The following are examples of possible questions wheelchair service personnel may ask to find out what the wheelchair user’s goal or goals are:

- Why did you come to the wheelchair service today?

- What should your wheelchair help you do?

The following are examples of possible goals:

- I need to be able to reach the well to collect water.

- I need to be able to get into a lift to reach my apartment.

- I need to be able to get my wheelchair into a small car.

- I would like to be more comfortable when sitting.

- I would like to be able to sit for longer in my wheelchair before I get tired.

- I need to be able to get in and out of the wheelchair myself.

- I need to be able to sit at a desk to use the computer.

- I would like to be able to visit my family and need a wheelchair that I can take on the bus.

Physical Condition[edit | edit source]

The ‘diagnosis/physical issues’ part of the wheelchair assessment form is important because some of the features of different diagnosis and physical issues, as we covered under Wheelchair Users, can affect the choice of wheelchair and additional postural supports.

Sometimes the wheelchair user may not know the name of their diagnosis or condition. It is also possible that no diagnosis has been made. In this case identify any specific physical issues and continue the assessment. Some physical issues that wheelchair users may experience can have a direct impact on choosing the most appropriate wheelchair.

Spasticity / Uncontrolled Movement[edit | edit source]

Some wheelchair users may have problems with sudden uncontrolled movements and spasticity, which can be triggered in a number of different ways including; the position of the person’s hip, knee and ankle; touch and movement of the wheelchair, particularly over rough/bumpy ground such as cobble stones.

Considerations for Wheelchair Provision

- Find out how the uncontrolled movements affect the wheelchair user and problem solve with them.

- Some supports or adjustments to the wheelchair may help to reduce spasms and uncontrolled movements including:

- supporting to help control the posture of the pelvis;

- adjusting the wheelchair seat to backrest angle so that the wheelchair user sits with their hips bent slightly more than neutral;

- positioning the footrests so that the knees are bent slightly more than neutral, ‘tucking’ the feet in; trying different angles of footrests.

- Straps may help give a wheelchair user more control over their legs and feet. If a strap is used, it should fasten with Velcro so that it will release if the wheelchair user falls out of the wheelchair.

- If the movements are very strong, consider:

- a solid seat and backrest support;

- selecting a wheelchair with an adjustable rear wheels position. The rear wheels can be positioned in the ‘safe’ position to make the wheelchair more stable/less tippy;

- Providing an anti-tip bar to stop the wheelchair from tipping over backwards.

- This is why it is very important for a wheelchair user to propel the wheelchair.

Altered Muscle Tone[edit | edit source]

Problems with muscle tone can be a problem for some wheelchair users. It is a common problem for people who have cerebral palsy [1], brain injury [2], SCI [3], and stroke [4][5]. The term muscle tone refers to the resistance/tension in resting muscle when it is being moved. [5] Normal muscle tone allows the limb or joint to be moved freely and easily. However some people may have muscle tone that is too high or too low.

High Muscle Tone[edit | edit source]

There is more resistance/tension, so it is harder to move a limb or joint. [1] A person with high muscle tone will usually find it difficult/awkward to move the affected limb or joint, and movement may be slow. Some people with high tone can move only in a certain ‘fixed’ pattern. [2] If the muscle tone is very high, almost no movement is possible.

Low Tone [edit | edit source]

There is less resistance, so it is easy to passively move the limb or joint. However, a person with a low muscle tone may find it difficult to begin movement, and may also find controlling their movement difficult. Low muscle tone is sometimes described as ‘floppy or flaccid’. If the tone is very low, it may be very difficult for the person to move.[1]

Common characteristics that may affect Wheelchair Provision;

The degree of difficulty caused by muscle tone depends on how severe the problem is, and which muscles are affected. Some possible difficulties for wheelchair users who have problems with muscle tone include: [1][2][6]

- reduced balance;

- difficulty sitting upright and comfortably;

- reduced muscle control, which can affect how easily the wheelchair user can carry out different tasks including propelling their wheelchair and transferring;

- When there is considerable high or low muscle tone, there can be difficulty and increased risk of aspiration with eating, drinking, swallowing and breathing. Aspiration is a life-threatening problem;

- Increased risk of the development of fixed non-neutral postures;

- For some wheelchair users, high muscle tone can become greater with emotion, or when he/she is trying very hard to do something;

- High and low muscle tone can be a risk factor for hip dislocations.

Considerations for Wheelchair Use; [2]

When touching or helping to move a wheelchair user who has high or low muscle tone, these tips may help:

- explain what you are going to do before you do it;

- move slowly and allow for the time it takes for a wheelchair user with low or high muscle tone to react;

- provide firm, comfortable support with your hands and arms so that the wheelchair user is well supported;

- when strong high tone causes the whole body or whole limb to straighten, the tone can sometimes be calmed by bending one joint. For example, if a whole leg straightens, bending the knee or hip can reduce the tone.

The amount of postural support needed will depend on a wheelchair user’s assessment. However some particular considerations for wheelchair users with high tone include:

- postural supports must be made strong enough to be effective with high muscle tone;

- high tone can cause points of high pressure between the user’s body and the wheelchair. Reduce this by distributing force over a larger surface area.

- Check for pressure. Teach the wheelchair user or their family member/caregiver to check the skin for signs of pressure;

- reducing the thigh-to-trunk angle can help to reduce strong patterns of high tone.

Fatigue[edit | edit source]

Some wheelchair users may regularly become tired during the day. This may be because of the additional effort and energy they use to sit upright and carry out activities, or the nature of their condition.

Fatigue can be a problem for some elderly people, or some people with progressive conditions (50, 51).

Common characteristics that may affect Wheelchair Provision;

- may be able to sit upright, however cannot stay upright for long due to fatigue;

- if wheelchair users find it hard to maintain an upright posture due to fatigue, they are at more risk of developing postural problems.

Considerations for Wheelchair Use;

- Try to find out what it is that makes the wheelchair user tired. This will help you to find the best solution for them.

- When deciding how much postural support to provide, consider the effect of fatigue. During the wheelchair assessment the wheelchair user may have more energy, and appear to need less support. Discuss carefully with the wheelchair user how much support they need when they are most tired.

- Consider alternative resting positions i.e. a tray with a cushion can allow someone to lean forward on their arms; tilt in space is another resting position.

- Planning to have rests out of the wheelchair during the day may make it possible to sit more comfortably for longer.

Dislocated Hips[edit | edit source]

There is a higher prevalence of the hip dislocation in children who have never been able to walk independently [7][8][9] . This is because the socket (acetabulum) on the pelvis is soft when children are born, and the round head of the femur shapes the socket when the leg is moving,or when weight is pushing through it when standing. If the hip joint does not form correctly, this can lead to dislocation.

It is also very common with children who have tight muscles and high tone around the hip and pelvis and tend to always sit or lie with their legs to one side [8]. This can be a problem for people with cerebral palsy [8][10] or traumatic brain injury [10].

For children who haven’t walked and have a tendency to lie with both legs to one side (windswept): the hip, which is closest to the mid line of the body (adducted) and turned in (internally rotated) is the one most likely to dislocate [11].

When children have low tone around the hip joint, they can also be at risk of hip dislocation. This is because the muscles and ligaments are not strong enough to hold the two parts of the hip joint together (the acetabulum and the head of the femur). A dislocated hip is not always painful [12][13][14].

Considerations for Wheelchair Use;

- Some indications that a person may have a dislocated/subluxed hip are:– one leg appears shorter than the other leg (60);

- their leg is always positioned closer to the mid line;

- there is pain when the hip is moved [2];

- when carrying out a range of motion of the hip it may not be possible to take the thigh to the neutral position or to the outside of the body;

- it is not possible to fully straighten the hips.

- Research shows that the following can help to reduce the tendency for hip dislocation:

- When assessing a child or adult who has any of the signs of a possible dislocated hip, move the hips gently and avoid causing pain.

- If you are not sure if a child or adult has dislocated hips refer the child to a doctor/paediatrician or experienced physiotherapist (if possible) for further advice.

- When providing a wheelchair and postural support for any child or adult with a hip dislocation or suspected hip dislocation:

- avoid postures, which cause pain;

- support their pelvis and trunk in neutral (as close to neutral as possible); and then support the hips and thighs as close to neutral as possible. Avoid ‘overcorrecting’ the leg posture as this may cause the pelvis to move away from neutral and/or cause pain;

- check what position the person sleeps in. Advise on a sleeping position that avoids windsweeping of the legs, and the legs from being squeezed tightly against each other.

Lifestyle and Environment[edit | edit source]

These questions gather information about where the wheelchair user lives and the things that he/she needs to do in the wheelchair.

Existing Wheelchair[edit | edit source]

These questions help to find out if the wheelchair user’s existing wheelchair is meeting his/her needs, and if not, why not.Physical Assessment[edit | edit source]

Physical assessment is the second part of the assessment process and includes:

Identifying the Presence, Risk of or History of Pressure Sores[edit | edit source]

Identifying the Method of Propulsion[edit | edit source]

it is important to find out how the wheelchair user will push, as this can affect the choice of wheelchair and the way it is set up

Taking Measurements[edit | edit source]

Four measurements from the wheelchair user are needed to choose the best available size of wheelchair for that person. each measurement relates to the wheelchair.

Measuring Tools[edit | edit source]

- Use a retractable metal tape measure (pictured on the right).

- clipboards/bookscanbeusedtohelpmeasure accurately (see How to take body measurements).

- Largecallipersareanadditionaltoolthatcanbe very useful. These can be made locally from wood.

- Foot-blocks can be used to support the wheelchair user’s feet at the correct height.

How To Take Body Measurements[edit | edit source]

- Ask the wheelchair user to sit as upright as possible.

- The wheelchair user’s feet should be supported on the floor or on foot-blocks if they cannot reach the floor comfortably.

- For all measurements, make sure the tape measure is held straight and the wheelchair user is sitting upright. Holding a clipboard/book on either side of the wheelchair user can help in obtaining an accurate measurement.

- Bend down to ensure you are viewing the tape measure at the correct angle.

Assessing Wheelchair Skills[edit | edit source]

- Finding out how the wheelchair user sits and what additional postural support they may need through:

- Observing sitting posture without support;

- Carrying out a pelvis and hip posture screen. Pelvis and hip posture screening helps to understand how any problems around the pelvis or hips may be affecting the wheelchair user’s sitting posture;

- Carrying out hand simulation. The wheelchair service personnel uses their hands to ‘simulate’ the support that a wheelchair and additional postural supports may provide;

- Taking Measurements.

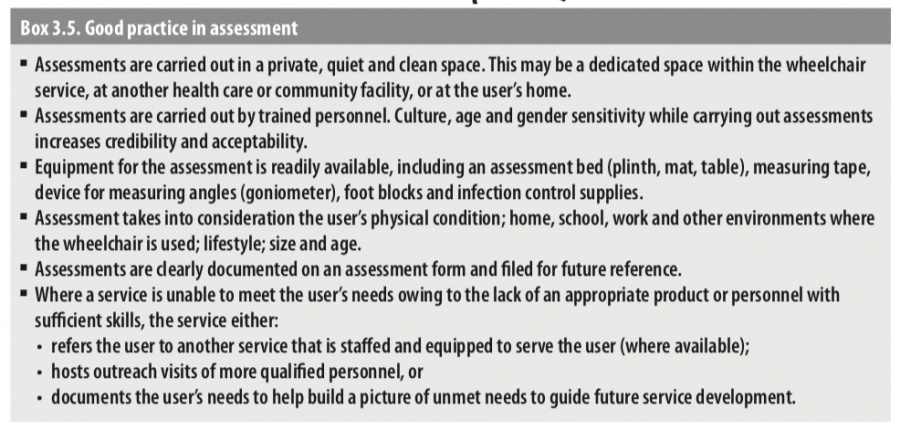

Good Practice[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 World Health Organization. (1993). Promoting the development of young children with cerebral palsy. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1993/WHO_ RHB_93.1.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 World Health Organzation, United States Department of Defense, Drucker Brain Injury Center MossRhab Hospital. (2004). Rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_DAR_01.9_eng.pdf

- ↑ Frederick M Maynard et al., International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, American Spinal Injury Association, 1996

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2012). Stroke, Cerebrovascular Accident. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/cerebrovascular_accident/en

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Martin,K.,Kaltenmark,T.,Lewallen,A.,Smith,C.,&Yoshida,A.(2007).Clinical characteristics of hypotonia:A survey of pediatric physical and occupational therapists. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 19, 217–226.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (1996). Promoting independence following a spinal cord injury:A manual for midlevel rehabilitation workers. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc. who.int/hq/1996/WHO_RHB_96.4.pdf

- ↑ Soo, B., et al. (2006). Hip displacement in cerebral palsy.The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 88, 121–129

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Scrutton, D., Baird, G., & Smeeton, N. (2001). Hip dysplasia in bilateral cerebral palsy: incidence and natural history in children aged 18 months to 5 years. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 43, 486–600

- ↑ Lonstein, J., & Beck, K. (1986). Hip dislocation and subluxation in cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6, 521–526

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 World Health Organzation, United States Department of Defense, Drucker Brain Injury Center MossRhab Hospital. (2004). Rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_DAR_01.9_eng.pdf

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pope, P. (2007). Severe and complex neurological disability: Management of the physical condition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited.

- ↑ Sherk, H., Pasquariello, P., & Doherty, J. (2008). Hip dislocation in cerebral palsy: Selection for treatment. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 25(6), 738–746. 65

- ↑ Moreau, M. et al. (1979). Natural history of the dislocated hip in spastic cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 21(6), 749–753.

- ↑ Knapp, R., & Cortes, H. (2002). Untreated hip dislocation in cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 22, 668–671.

- ↑ Pountney,T., Mandy,A., Green, E., & Gard, P. (2009). Hip subluxation and dislocation in cerebral palsy – a prospective study on the effectiveness of postural management programmes. Physiotherapy Research International, 14(2), 116–127.

- ↑ Health Centre for Children. (2011). Evidence for practice: Surveillance and management of hip displacement and dislocation in children with neuromotor disorders including cerebral palsy.Vancouver, BC:Tanja Mayson.

- ↑ William Armstrong, Johan Borg, Marc Krizack, Alida Lindsley, Kylie Mines, Jon Pearlman, Kim Reisinger, Sarah Sheldon. Guidelines on the Provision of Manual Wheelchairs in Less Resourced Settings. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008.