Dermatomes

Original Editor - Lucinda Hampton

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Anas Mohamed, Lucinda hampton, Joao Costa, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Blessed Denzel Vhudzijena, Rachael Lowe and Kim Jackson

Lead Editors

Dermatomes[edit | edit source]

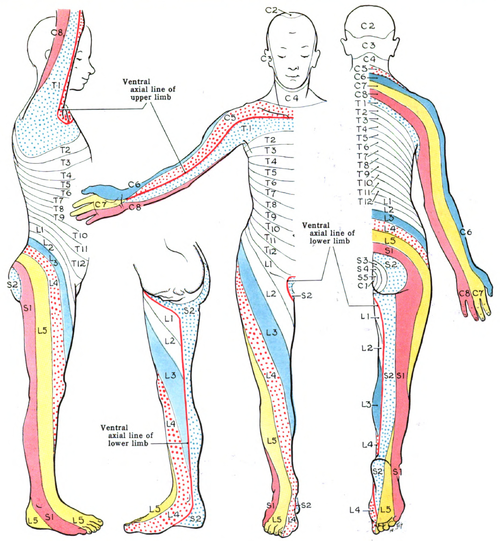

The term “dermatome” is a combination of two Greek words; “derma” meaning “skin”, and “tome”, meaning “cutting” or “thin segment”. Dermatomes are areas of the skin whose sensory distribution is innervated by the afferent nerve fibres from the dorsal root of a specific single spinal nerve root, which is that portion of a peripheral nerve that “connects” the nerve to the spinal cord.

Nerve roots arise from each level of the spinal cord (e.g., C3, C4), and many, but not all, intermingle in a plexus (brachial, lumbar, or lumbosacral) to form different peripheral nerves as discussed above. This arrangement can result in a single nerve root supplying more than one peripheral nerve. For example, the median nerve is derived from the C6, C7, C8, and T1 Nerve Roots, whereas the ulnar nerve is derived from C7, C8, and T1.

In total there are 30 dermatomes that relay sensation from a particular region of the skin to the brain - 8 cervical nerves (note C1 has no corresponding dermatomal area), 12 thoracic nerves, 5 lumbar nerves and 5 sacral nerves. Each of these spinal nerves roots.[1] Dysfunction or damage to a spinal nerve root from infection, compression, or traumatic injury can trigger symptoms in the corresponding dermatome. [2]

| Nerve Root | Dermatome | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | C2 | Supply Skin of Neck | Temple, Forehead, Occiput |

| C3 | Entire Neck, Posterior Cheek, Temporal Area, Prolongation forward under Mandible | ||

| C4 | Shoulder Area, Clavicular Area, Upper Scapular Area | ||

| C5 | Supply the Arms | Deltoid Area, Anterior aspect of entire arm to base of thumb | |

| C6 | Anterior Arm, Radial side of hand to thumb and index finger | ||

| C7 | Lateral Arm and Forearm to index, long, and ring fingers | ||

| C8 | Medial Arm and forearm to long, ring, and little fingers | ||

| Thoracic | T1 | Medial side of forearm to base of little finger | |

| T2 | Supply the chest and abdomen | Medial side of upper arm to medial elbow, pectoral and midscapular areas | |

| T3 - 6 | Upper Thorax | ||

| T5 - 7 | Costal Margin | ||

| T8 - 12 | Abdomen and Lumbar Region | ||

| Lumbar | L1 | Back, over trochanter and groin | |

| L2 | Back, front of thigh to knee | ||

| L3 | Supply Skin of Legs | Back, upper buttock, anterior thigh and knee, medial lower leg | |

| L4 | Medial buttock, latera thigh, medial leg, dorsum of foot, big toe | ||

| L5 | Buttock, posterior and lateral thigh, lateral aspect of leg, dorsum of foot, medial half of sole, first, second, and third toes | ||

| Sacral | S1 | Buttock, Thigh, and Leg Posterior | |

| S2 | Supply Groin | Same as S1 | |

| S3 | Groin, medial thigh to knee | ||

| S4 | Perineum, genitals, lower sacrum | ||

| Coccygeal | The dermatome corresponding with the coccygeal nerves is located on the buttocks, in the area directly around the coccyx.[4][5] | ||

History[edit | edit source]

The idea of dermatomes originated from initial efforts to associate anatomy with the physiology of sensation. Multiple definitions of dermatomes exist, and several maps are commonly employed. Although they are valuable, dermatomes vary significantly between maps and even among individuals,[6] with some evidence suggesting that current dermatome maps are inaccurate and based on flawed studies.[7] [8]

The medical profession typically recognised two primary maps of dermatomes. Firstly, the Keegan and Garret Map (Fig.1) from 1948, which illustrates dermatomes in alignment with the developmental progression of the limb segments. Secondly, the Foerster Map from 1933, which portrays the medial area of the upper limb as being innervated by T1-T3, depicting the pain distribution from angina or myocardial infarction. This latter map is the most frequently used in healthcare and accounts for the dermatomes used in the American Spinal Cord Injury Association Impairment Scale (ASIA Scale). In recent years there have been few attempts at verifying these original dermatome maps. Lee et al conducted an in-depth review that examined the discrepancies among dermatome maps. They put forth an “evidence-based” dermatome map that combined elements of previous maps (Fig.3). Though the application of the term “evidence-based” may be somewhat questionable, their proposed map represents a systematic attempt to synthesise the most credible evidence available.[6][7]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

Testing of dermatomes is part of the neurological examination. They are primarily used to determine whether the sensory loss on a limb corresponds to a single spinal segment, implying the lesion is of that nerve root (i.e., radiculopathy), and to assign the neurologic “level” to a spinal cord lesion[9].

Technique[edit | edit source]

Dermatome Testing is done ideally with a pin and cotton wool. Ask the patient to close their eyes and give the therapist feedback regarding the various stimuli. Testing should be done on specific dermatomes and should be compared to bilaterally.

- Light Touch Test - Light Touch Sensation - Dab a piece of cotton wool on an area of skin [10]

- Pinprick Test - Pain Sensation - Gently touches the skin with the pin ask the patient whether it feels sharp or blunt

During the review of systems, asking the patient to carefully describe the pattern or distribution of sensory symptoms (e.g., tingling, numbness, diminished, or absent sensation) provides the therapist with preliminary information to help guide the examination and to assist in identifying the dermatome(s) and nerve(s) involved.[11]

Light touch dermatomes are larger than pain dermatomes. When only one or two segments are affected, testing for pain sensibility is a more sensitive method of examination than testing for light touch.[9]

Controversies[edit | edit source]

Dermatomes have a segmented distribution throughout your body. The exact dermatome pattern can actually vary from person to person. Some overlap between neighboring dermatomes may also occur. There exist some discrepancies among published dermatome maps based on the methodologies used to identify skin segment innervation.

In a clinical commentary, Downs and Laporte discuss the history of dermatome mapping, including the variations in methodologies employed, and the inconsistencies in the dermatome maps used in education and practice.[11] [[Laporte C. Conflicting dermatome maps: educational and clinical implications. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Jun;41(6):42[12]7-34.]]

Clinical Significance[edit | edit source]

Dermatomes are important because they can help to assess and diagnose a variety of conditions. Neurological screening of dermatomes helps to assess patterns of sensory loss that can suggest specific spinal nerve involvement. For instance, symptoms that occur along a specific dermatome may indicate disruption or damage to a specific nerve root in the spine.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Wikipedia Dermatome. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dermatome_(anatomy) (last accessed 23.4.2019)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Medical news today What and where are dermatomes? Available:https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-are-dermatomes (accessed 25.5.2022)

- ↑ M Roehrs. Dermatomes. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYZBH6NX8wg&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 23.4.2019)

- ↑ Medical news today What and where are dermatomes? Available:https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-are-dermatomes (accessed 25.5.2022)

- ↑ David J. Magee. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 6th edition. Elsevier. 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Apok V, Gurusinghe NT, Mitchell JD, Emsley HC. Dermatomes and dogma. Practical neurology. 2011 Apr 1;11(2):100-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lee MW, McPhee RW, Stringer MD. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Australasian Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2013 Jun;18(1):14-22.

- ↑ Downs MB, Laporte C. Conflicting dermatome maps: educational and clinical implications. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Jun;41(6):427-34.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Liebenson C, editor. Rehabilitation of the spine: a practitioner's manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/dermatome (accessed 25.5.2022)

- ↑ Slide share. Dermatomes and myotomes. Available from: https://www.slideshare.net/TafzzSailo/special-test-for-dermatomes-and-myotomes (last accessed 23.4.2019)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Susan B.O'Sullivan, Thomas J. Schmitz, George D. Fulk. Physical Rehabilitation. 6th edition. F. A. Davis Company. 2014.

- ↑ Downs MB, Laporte C. Conflicting dermatome maps: educational and clinical implications. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Jun;41(6):427-34.