Dysphagia

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing liquid or solid food due to disruption in swallowing mechanism from the mouth to pharynx.[1] Dysphagia can lead to severe complications [1][2]:

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition

- Death because of choking

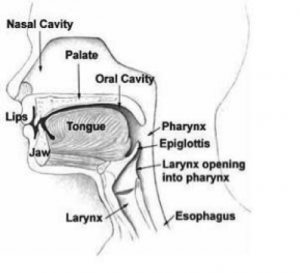

Physiology of Swallowing[edit | edit source]

A sound knowledge of anatomy and physiology of swallowing and eating helps in the diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia.[3]There are four stages involved in the physiology of swallowing[3] :

- Oral preparatory stage: This stage prepares bolus for the next stage i.e, propelling food to pharynx and it prevents liquid and solid food from entering to pharynx until the bolus is ready for swallowing food.

- Oral propulsive stage: As the solid and liquid food is ready to swallow, the bolus is transferred into oropharynx with help of tongue,

- Pharyngeal stage :Main feature of this stage is to prevent food from entering it into respiratory tract and prevent from aspiration.

- Esophageal stage: This stage starts after the bolus enters the Upper Esophageal Sphincter(UES).In this phase, through the peristaltic movement and with help of gravity, food enters the stomach.

Physiologically, swallowing dominates the respiration because of closure of the airway by elevation of the soft palate and tilting of the epiglottis and also of neural suppression of respiration in the brainstem. The duration of respiratory pause is different while eating liquid and solid bolus. [3]

There are various causes for alteration in normal swallowing physiology. Broadly it can be categories into two heading :

- Structural abnormalities

- Functional abnormalities

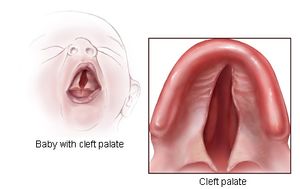

Structural Abnormalities[edit | edit source]

It can be acquired or congenital. Cleft palate, cervical osteophytes, webs or strictures in the passage are some of the examples of the structural abnormalities. The abnormalities might affect in any stage of the swallowing and alter the normal physiology. [3]

Functional Abnormalities[edit | edit source]

Dysfunction in any of the four stages of swallowing process can affect the swallowing physiology an cause dysphagia.

Problem in oral stage of swallowing may lead to drooling of the food, dehydration, feeling of food trapped in oral cavity. and difficulty chewing and mastication.

Dysfunction in the pharyngeal stage leads to impaired swallowing initiation, feeling of retention of bolus in pharynx. Impairment in pharyngeal stage may result in nasal regurgitation and aspiration (due to insufficient UES opening).

Esophageal dysfunction is common and is often asymptomatic. Esophageal dysphagia can lead to feeling of retention of food in the esophagus which might lead to aspiration of food[3].

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are many bedside and instrumental tools available for the diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia. Dysphagia evaluation tools can be grouped broadly as

- Imaging (Ultrasound, Video fluoroscopy, Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing, and Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing)

- Non imaging(beside assessment tools, and pharyngeal manometry).[2]

Management and Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitative exercises changes and improves the swallowing physiology in force, speed or timing, with the goal being to produce a long-term effect, as compared to compensatory interventions used for a short-term effect. Rehabilitative exercises also involve retraining the neuromuscular systems to bring about neuroplasticity, since pushing any muscular system in an intense and persistent way will bring about changes in neural innervation and patterns of movement.[4] Rehabilitation exercise can be broadly divided into :

- Swallowing exercises

- Non-swallowing exercises

Swallowing Exercises[edit | edit source]

Swallowing exercises often are used to treat dysphagia with the goal of altering swallowing physiology and promoting long-term changes. Exercises are expected to impact swallowing mechanics and impact bolus flow.[5] Effortful swallow, Mendelsohn, super-supraglottic, Masako are some of the swallowing exercises. Swallowing exercises follow many of the neuroplasticity principles listed below[4]:

- Use it or loose it

- Use it and improve it

- Specificity

- Transference

- Intensity

Non-Swallowing Exercises[edit | edit source]

Non-swallowing exercises are those that do not involve the act of swallowing, for example tongue strengthening exercises. Non-swallowing exercises can be

done by patients who cannot eat orally (are tube fed) or those post-surgery who are temporarily restricted from eating orally. Shaker head lift, tongue strengthening, Lee Silverman voice treatment, expiratory muscle strength training are some of the non-swallowing exercises. Non-swallowing exercises follow few neuroplasticity principles and they are[4]:

- Transference

- Intensity

Therapeutic Interventions[edit | edit source]

Therapeutic techniques can be divided into those used as :

- Compensatory strategies (Head Rotation (Head Turn), Chin Tuck (Head Flexion). Head Tilt and Bolus Viscosity, Texture, and Volume Modifications)

- Exercises (Tongue Hold, Shaker Exercise)

- Those used as both compensatory strategies and/or exercises (Supraglottic Swallow, Super-Supraglottic Swallow, Effortful Swallow, Mendelsohn Maneuver)

- Alternate methods (Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES), Oral Stimulation and Other Interventions )

Head Rotation (Head Turn)[edit | edit source]

Head rotation is a compensatory strategy used for patients with unilateral pharyngeal and/or laryngeal weakness as well as reduced UES opening.[5]

- Instruction given: While swallowing food, turn your head to the weaker side as if you are looking over your shoulder.[5]

- Physiological benefits:

Chin Tuck (Head Flexion)[edit | edit source]

The chin tuck (head flexion) is used for patients who have decreased airway protection associated with delayed swallow initiation and/or reduced tongue base retraction.[5]

- Instruction: While swallowing food, bring your chin to the chest and maintain this posture throughout the duration of the swallow.

- Physiological benefits:

- Expansion of vallecular recesses

- Approximation of tongue base toward pharyngeal wall

- Reduction in distance between hyoid and larynx

- Increases duration of swallowing apnea during the swallow[5]

Head Tilt[edit | edit source]

The head tilt is used for patients with unilateral oral weakness. [5]

- Instruction: While swallowing, tilt your head like you’re trying to touch your ear to your shoulder. Swallow while maintaining this position.

- Physiological benefits:

- It directs the bolus to the stronger side of the oral cavity[5]

Bolus Viscosity, Texture, and Volume Modifications[edit | edit source]

- Increasing the volume and/or viscosity for liquids is another technique used for patients who have poor oral control of thin liquids and/or demonstrate reduced airway protection.

- Some patients may benefit from texture-modified foods.[5]

Supraglottic Swallow[edit | edit source]

The supraglottic swallow is used for patients who demonstrate reduced airway protection during the swallow and delayed swallow initiation.

- Instruction: Before swallowing, first, inhale deep then hold your breath, continue to hold your breath and swallow immediately after you swallow (before you inhale), cough then immediately swallow again.

- physiologic benefits [5]:

- Increases airway closure and

- Increases UES opening during the swallow

Super-Supraglottic Swallow[edit | edit source]

Super-supraglottic swallow differ from supraglottic swallow only when implementing effortful breath hold

- Instruction: Before swallowing, take a breath and hold it tightly while bearing down; continue to hold your breath and bear down as you swallow; immediately after your swallow (before you inhale) cough then immediately swallow hard again (before you inhale).’’

- Physiological benefit[5]:

- Patient has earlier tongue base movement

- Higher hyoid position at swallow onset

- Increased hyoid movement as well as longer bolus transit time

- Note: Both the supraglottic swallow and the supra-supraglottic swallow maneuvers may result in Valsalva and can result to arrhythmia in stroke patients during treatment sessions. Hence, clinicians should be mindful of using these maneuvers in stroke patients especially in those with coexisting heart disease.[5]

Effortful Swallow[edit | edit source]

The effortful swallow is used for patients who present with clinically significant residue in the valleculae and/or pyriform sinuses as well as for patients who may have decreased airway closure.

- Instructions: while swallowing, squeeze your throat muscles as hard as you can.

- Physiological benefits:

- It increases hyolaryngeal excursion, duration of hyoid elevation

- Increases UES opening

- Increases laryngeal closure

- Increases lingual pressures

- Increases peristaltic amplitudes in the distal esophagus

- Increases pressure and duration of tongue base retraction[5]

Mendelsohn Maneuver[edit | edit source]

This technique is used for patients with decreased hyolaryngeal excursion and/or decreased duration of UES opening.

Before giving command, patient is suggested first to fee laryngeal elevation through palpation while swallowing the saliva.

- Instruction: After palpating the thyroid cartilage, feel the cartilage elevation while swallowing, now hold it up for several second and swallow the food while holding it up.

- Physiologic benefits:

- It increases time and duration of hyolaryngeal excursion

- Increased time of UES opening, pharyngeal peak contractions,

- Increased bolus transit time and duration, and pressure of tongue base contact.[5]

Tongue Hold[edit | edit source]

The tongue hold is used for reduced tongue base, and pharyngeal wall contact.

- Instruction: While swallowing the food, hold the anterior tongue (slightly posterior to the tongue tip) between the teeth.

- Physiological benefits: It increases anterior bulging of the posterior pharyngeal wall.[5]

Shaker Exercise[edit | edit source]

The Shaker Exercise is used for patients who have decreased UES opening and weakness of the suprahyoid muscles.

- Instruction: Patient position is supine and patient is asked to complete 3 head lifts sustained for 1 min each; 1 min rest period between each head lift; then complete 30 consecutive head lifts holding for 2 s each’’ The suggested frequency is three times each day for 6 consecutive weeks.

- Physiological benefits:

- It increases anterior hyolaryngeal excursion

- It increases UES opening

- It strengthens suprahyoid muscles

- It enhances thyrohyoid shortening.[5]

Masako[edit | edit source]

In this maneuver, patient is asked to protrude the tongue and hold it between the teeth while swallowing.[4]

Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES)[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is a treatment where electrodes are placed on the anterior neck and an electrical current evokes a muscle contraction. NMES treatment is typically used as an adjunct modality concurrently while the patient swallows and/or performs a traditional exercise. [5]

Oral Stimulation and Other Interventions[edit | edit source]

Oral stimulation techniques and some other interventions used in dysphagia management are listed below:[5]

- Tactile-thermal stimulation

- lingual, and labial strengthening

- Ice massage to the throat, base of tongue, and the posterior pharyngeal wall for 10 s with rubbing and light compression (for patients with supranuclear lesion)

- Lip muscle training

- lingual exercise following I-PRO (isometric progressive resistance oropharyngeal)

- Trans-cranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

- Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Balamurali K, Sekar D, Thangaraj M, Kumar MA. Dysphagia in Patients with Stroke: A Prospective Study. International Journal of Contemporary Medicine Surgery and Radiology.2018;3(2):B11-B120

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 González-Fernández M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, Christian AB. Dysphagia after stroke: an overview. Current physical medicine and rehabilitation reports. 2013 Sep 1;1(3):187-96.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2008;19(4):691-707.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Langmore SE, Pisegna JM. Efficacy of exercises to rehabilitate dysphagia: a critique of the literature. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2015;17(3):222-229.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 Vose A, Nonnenmacher J, Singer ML, González-Fernández M. Dysphagia management in acute and sub-acute stroke. Current physical medicine and rehabilitation reports. 2014;2(4):197-206.