Hamate Fracture

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Hamate fractures are rare and underreported. These injuries are usually misdiagnosed or confused with simple wrist sprains. Delayed diagnosis is not uncommon.

The hamate is a triangular-shaped bone that forms part of the distal carpal row, articulating with the capitate (radially), triquetrum (proximally) and fifth and fourth metacarpals (distally).

Considering its unique anatomy, hamate fractures usually get subdivided into two broad groups: hook fractures and body fractures.[1]

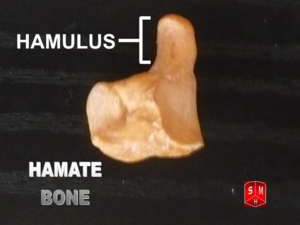

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The hamate bone is one of eight carpal bones, it is a triangular bone, composed of a body and a hook (hamulus), located on the ulnar side of the distal carpal row.

The hamate is a triangular-shaped bone that forms part of the distal carpal row, articulating with the capitate (radially), triquetrum (proximally) and fifth and fourth metacarpals (distally).[1]

The Guyon canal (a fibro-osseous structure that forms a groove between the pisiform and the hook of the hamate) carries the ulnar artery and nerve, for this reason, hook fractures should suggest a high probability of ulnar artery and nerve damage.[1]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

- The hook of hamate fracture frequently occurs in sports where a firm grip is required, such as tennis, baseball, and golf.[1]

- Body of the hamate fractures are related to higher energy trauma such as a punch and may be associated with concomitant carpal fractures and carpometacarpal dislocations. Body fractures are less common.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Hamate fractures are uncommon hand injuries and account for 2 to 4% of carpal fractures. Hamate fractures (hook and body) tend to occur in young, active patients. They are unusual in children.[1]

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

- The hook of hamate injuries are mainly due to repeated impact, usually, a sporting activity (racket, club, bat) exerting a direct force against the hamate[1].

- Avulsion fractures of the hook may also occur, as the hook of the hamate serves as an attachment point for three tendons (opponens digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi and flexor carpi ulnaris)[1].

- Body of the hamate fracture is a consequence of a direct blow over the hypothenar eminence or a strong dorsopalmar compression[1].

- A body fracture may also accompany high energy trauma resulting in wrist fracture-dislocations.

- Body fractures can lead to axial carpal instability.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Though clinical findings may be vague and unspecific, there are some tests that are useful if a hook of hamate fracture is suspected[1].

- Suspicion should be high in young athletes with pain along the ulnar aspect of the wrist.

- Chronic wrist pain is common with a hook of the hamate fracture, with tenderness and exquisite pain over the hypothenar area.

- Paresthesias along the ring and small finger are relatively common in chronic cases.

- Weakened grip strength is typical. Grasp maneuvers provoke pain along the ulnar side of the wrist.

- Fourth and fifth metacarpal pain is related to hamate injuries; even metacarpal deformity may be an indirect sign of the body of the hamate fracture.

- Pull test: in the hook of the hamate fractures, active flexion of distal interphalangeal joints of the ring and small finger may cause pain. This phenomenon is the result of flexor tendons forces attached at the fracture site.

As body hamate fracture are related to higher energy trauma and associated injuries, diagnosis tends to be acute. Swelling and tenderness over the dorsal ulnar wrist frequently present in hamate body fractures.[1]

Displaced hamate fragments and haematoma, as well as nonunion of the hook of the hamate, can lead to neuropathy of the deep branch of the ulnar nerve, lesion of the median nerve, or even rupture of deep flexor tendons IV and V.

The fracture fragments may injure the nerves directly or swelling and inflammation may injure them indirectly.[2][3][4][5]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

An oblique x-ray view or a carpal tunnel view should be considered as part of the initial diagnostic investigations. It can help with diagnosis and give further important information to aid appropriate management.[7]

Standard radiographs possess a high rate of false negatives, with a 70% sensitivity.

Specific views include carpal tunnel projection and semisupine oblique radially deviated projection.

- CT scan is often necessary to reach proper diagnosis (100% sensitivity).

- MRI scan is only necessary for chronic disease (avascular necrosis)[1]

The hook of the hamate pull test (see above)is a clinical test for diagnosing a hook of hamate fracture.[9]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Hand-held dynamometry/grip strength

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Hook Fractures[1][edit | edit source]

- Acute, nondisplaced: Immobilization, ulnar gutter cast for six weeks. There is still debate whether patients may profit from initial surgical treatment in this type of fractures. Sport players will usually benefit from early surgical management, returning to sports activities in three months.

- Acute, displaced: Excision of a bony fragment is the gold standard procedure. Open reduction and internal fixation (screws or Kirschner wires) is another proven treatment. Both alternatives showed similar clinical results.

- Chronic pain, nonunion: These signs require fracture pinning with bone grafting.

Body Fractures[1][edit | edit source]

- Acute, nondisplaced: Immobilization, six-week cast.

- Acute, displaced: Open reduction and internal fixation (Kirschner wires, grid plate, or headless compression screws).[1]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is important.

In conservative treatment, therapy should begin right after cast removal.

- Following any immobilisation of the hand and wrist, there is usually loss of supination and pronation strength and range, as well as the loss of intrinsic muscle strength and control.

- Specific physiotherapy exercises are required to address this, and the entire upper limb may also need retraining to ensure good proximal stability returns to the upper limb complex, particularly if returning to sporting activities

Following ORIF, therapy should begin after a 3-week immobilization protocol. Post-surgery, the physical therapist will guide rehab, and report back to the other members of the team as to the progress or stagnation/regression of the rehabilitation process in coordination with the surgeon's rehabilitation protocol.

Hook excisions may start early therapy.

Rehabilitation protocol should last 4 to 6 weeks.[1]

- Depending on the injury passive and active exercises are explained and exercised. As the function and range of movement improve coordination exercises, exercises against resistance and exercises to restore strength can incorporated into the exercise program.[10]

- During the first days after injury, edema in the hand may be evident, resulting in decreased function of the hand. Positioning the hand above the elbow can assist in reducing the swelling.

- During the rehabilitation, physiotherapist uses passive mobilizations to normalize the ROM and the rolling and sliding motion of the involved joint. These mobilizations may include traction, translation and angular mobilizations.

During rehabilitation after plaster immobilization of the wrist, there will be some stiffness of the capsule in the wrist.

- Traction and translations are performed.

- The patient is also encouraged to mobilize as much as possible the affected joints to improve function and return to activity as quickly as possible.

- Patients are encouraged to actively mobilize the adjacent joints to avoid stiffening.

- In the hand wrist and finger flexors are muscles show an elevated tone and have the tendency to shorten. The flexors of the hand should be stretched and (as pain and swelling allows) add excentric training.

- Progressive resistance exercises are added when the fracture is sufficiently consolidated. The exercises consist of concentric and eccentric muscle activity, closed and open chain exercises. Resistance exercises are necessary to regain a good functionality of the hand.[11]

- Low-intensity ultrasound has been reported to be useful in promoting fracture healing, it accelerates the normal fracture repair process.[2]

Ultrasound treatment might be useful for nonunion caused by repeated stress, the ultrasound is a treatment for nonunion of the hook of the hamate and is an option in various treatment methods.[12]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis includes[1]:

- Flexor/extensor carpi ulnaris tendon injury

- Metacarpal/carpal bone fracture or contusion

- Triangular fibrocartilaginous complex tear

- Ulnar artery thrombosis

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

The decision between casting and surgery is based on the lifestyle demands of the patient. The athlete who does not want to risk healing a nonunion after casting may opt for surgery to minimize the time away from sport. Similarly, a patient with a job that requires repetitive grabbing, gripping or lifting may elect for excision to reduce the risk of an extended period of time away from work.[4]

Complications[edit | edit source]

- Nonunion

- Posttraumatic arthritis

- Avascular necrosis in proximal pole (body fractures)

- Ulnar nerve compression (Guyon´s canal)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Flexor digitorum profundus tendon rupture

- Ulnar artery thrombosis (hypothenar hammer syndrome)

- Ulnar artery compression

- Residual instability of fourth and/or fifth metacarpals[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Abrego MO, De Cicco FL. Hamate Fractures. 2021 Jul 18. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Guha AR, Marynissen H. Stress fracture of the hook of the hamate. Br J Sports Med. Jun 2002; 36(3):224-5. (B)

- ↑ Rainer Schmitt; Ulrich Lanz; Diagnostic imaging of the hand; THIEME; 2008

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mark D. Bracker; The 5-minute Sports Medicine Consult; Wolters Kluwer; 2011

- ↑ Kenneth A. Egol, Kenneth J. Koval, Joseph D. Zuckerman; Handbook of fractures; Wolters Kluwer; 2010

- ↑ Case courtesy of Dr Servet Kahveci, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 83341

- ↑ Vishal H Borse, James Hahnel, Adnan Faraj; Lessons to be learned from a missed case of Hamate fracture: a case report; Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research; 2010 Aug 27;5:64. (B)

- ↑ Case courtesy of Dr Servet Kahveci, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 83341

- ↑ Thomas W. Wright, Michael W. Moser, Deenesh T. Sahajpal; Hook of the hamate pull test; J Hand Surg Am. 2010 Nov; 35 (11): 1887-1889. (B)

- ↑ Dr. Louise M. van Dongen et al.; Handboek voor handrevalidatie theorie en praktijk; Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum; 2002

- ↑ Eric Van den Kerckhove et al.; De kinesitherapeutische behandeling van hand- en polsletsels Oefentherapie en ondersteunende technieken; Standaard uitgeverij; 2009

- ↑ Hirano K, Inoue G. Classification and treatment of hamate fractures. Hand Surg. 2005; 10(2-3):151-7. (A2)