Myasthenia Gravis: Case Study

Abstract[edit | edit source]

This project is a fictional case study developed by Physical Therapy students from Queen's University to help with the understanding of the implications of a Myasthenia Gravis (MG) diagnosis on physical therapy assessment and treatment. The case study shows the clinical presentation, expectation of symptoms, comorbidities, and impairments of a patient diagnosed with MG. The case also presents some objective measures and treatment options based on individualities of the patient’s disease presentation. It is important to note that MG symptoms can vary among individuals, so the following assessment, outcome measures, and treatment plan may not be appropriate for all individuals diagnosed with MG, and an individual assessment would be necessary to determine the best course of action for other patients.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease affecting the antibodies to receptors at the neuromuscular junction, causing muscle weakness and fatigue[1]. Individuals with MG have decreased acetylcholine and voltage-gated sodium channels due to damage of their postsynaptic membranes[2]. This dysfunction in the neuromuscular junction results in decreased response and amplitude of the corresponding muscles[2].

Comorbidities[edit | edit source]

Patients diagnosed with MG may present with several comorbidities. Since it is an autoimmune disorder, patients are at an increased risk for other autoimmune diseases such as Thymoma (thymus tumor) [1][3], Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [1][4][5], Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) [4][5], and Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 [1][3][4]. Some other common comorbidities include Hypertension, COPD [4], and an increased risk for respiratory infections due to muscle weakness and other issues related to prolonged corticosteroid use[3].

Presentation[edit | edit source]

This autoimmune disease is relatively uncommon with approximately 20 out of 100,000 individuals diagnosed with MG in the United States [6]. Reported prevalence in Ontario, Canada is similar with 32 out of 100,000 individuals[7]. In both Canada and the United States, there appears to be a greater incidence of younger women (<60 and <50 years old, respectively), diagnosed with MG[6][7]. Whereas, in Canada and the United States, incidence appears to be greater in older men (>60 and >50 years old, respectively)[6][7].

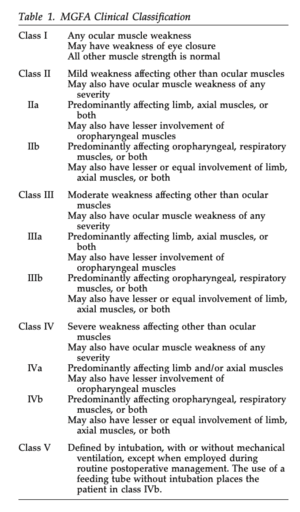

As seen in Table 1, the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America defines five main classes of MG with corresponding subclasses[8]. This system helps to determine a patient’s prognosis and potential response to treatment depending on their symptom severity[8].

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

The initial symptom that presents for two thirds of individuals:

- weakness of the extrinsic ocular muscles of the eyes[6]

- can present as ptosis, diplopia, and blurry visio

The symptoms then typically progress to include:

- other bulbar and limb muscles in approximately half of patients within two years[6]

One of the primary symptoms of MG:

- muscle fatigue

- Factors such as heat exposure, stress, and infection also worsen fatigue[6].

- weakness

Physiotherapy Implications[edit | edit source]

It is necessary for physiotherapists to take a comprehensive medical history to screen for the many comorbidities that might be associated with the diagnosis, including a screen for red flags. It is also important to take into consideration the patient's medications (especially corticosteroid use), and the presence of possible underlying conditions. These findings can limit some treatment approaches and be contraindications or precautions for some manual therapy or exercise treatments.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Maya Stevens is a 34-year-old, Caucasian woman who was recently diagnosed with MG two months ago. Mrs. Stevens reached out to her family doctor after experiencing a number of abnormal symptoms apart from her other diagnoses (rheumatoid arthritis and hypertension) and was referred to a neurologist who provided her with a diagnosis of MG. She was aware that a common comorbidity of these conditions is MG, and thought it was appropriate to seek medical advice. She was referred to physical therapy to address her concerns, and to learn preventative techniques to avoid a decline in function and to manage future symptoms associated with the disease. Mrs. Stevens is a motivated, pleasant individual who is prepared to take a rehabilitative approach to her diagnosis.

Subjective[edit | edit source]

History of Present Illness (HPI)[edit | edit source]

Patient reports feeling well in the morning, but becomes more fatigued in the afternoon as the day progresses. She has been increasingly stressed from returning back to work after maternity leave, taking care of her two young kids, and having a husband who works long hours. She has been taking care of many of the household duties and has a hard time caring for her kids. She initially noticed difficulty keeping her eyes open while attempting to take out her contacts at night, 9 months ago. Over the next month, her eye drooping became more persistent throughout the day and she began experiencing episodes of double vision. Additionally, she also noticed muscular fatigue in her shoulders while kayaking, as she isn’t able to paddle for as long without taking breaks. She describes her fatigue as more frequent, and like her “limbs aren’t working.” Other activities that are particularly bothersome are baking and grocery shopping. She also noticed increased shortness of breathing while kayaking, which has progressed to less exertional activities, such as entering the stairs into her home at the end of the day.

Past Medical History (PMHx)[edit | edit source]

Mrs. Stevens was diagnosed with RA five years ago and hypertension nine months ago, both of which are currently well maintained and have not caused any problems after giving birth to her second child.

Family History (FHx)[edit | edit source]

Both of Mrs. Stevens’ parents are alive, and her father was diagnosed with hypertension at the age of 30. In addition, her Great Aunt was diagnosed with MG at 52 years old[9].

Medications (MEDS)[edit | edit source]

- Methotrexate for RA (10 mg, 1x/week)

- Lisinopril for hypertension (5 mg, 1x/day)

- Women’s Multivitamin (1x/day)

- No current use of medication for MG

Social History (SHx)[edit | edit source]

Patient lives in Kingston, Ontario in a bungalow with four steps to enter the home with a railing on both sides. She lives with her husband and two kids (one and four years old). Mrs. Stevens works at a dental clinic as a receptionist and spends most of her day sitting, using the computer, and answering client questions or calls.

Health Habits (HH)[edit | edit source]

Mrs. Stevens does not smoke or use recreational drugs. She has one glass of wine every evening (6-7 drinks/week) to wind down.

Functional History (FnHx)[edit | edit source]

Prior to diagnosis, patient was fully independent in all bADLs, iADLs, ambulation, and family activities.

Current Functional Status (FnSt)[edit | edit source]

- Patient is independent in most bADLs, but becomes fatigued from prolonged walking (greater than 30 minutes).

- She is independent in iADLs in the morning, but becomes more fatigued throughout the day making it more difficult to clean, cook meals, shop, drive, or do housework.

- Patient has difficulty finding time to exercise with her busy schedule and is often fatigued which worsens with exercise.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

Upon observation, Mrs. Stevens is alert and oriented, making light conversation. Patient demonstrates some hoarseness of speech and displays an apical breathing pattern. She has right-sided asymmetrical ptosis with exertion, as well as forward head posture.

Vital Signs[edit | edit source]

- Heart Rate (HR): 74 beats per minute

- Respiratory Rate (RR): 18 breaths per minute

- Blood Pressure (BP): 128/82

- Radial Pulse: strong and regular

Active and Passive Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

Active and passive range of motion (AROM and PROM) were tested for all upper extremity and lower extremity joints. Mrs. Stevens demonstrates pain free AROM and PROM within normal limits bilaterally.

Strength[edit | edit source]

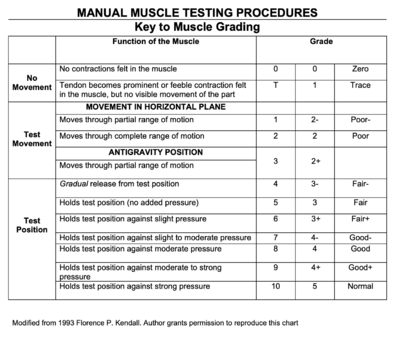

Manual Muscle Testing (MMT) was performed for upper extremity and lower extremity joints bilaterally, as well as for the cervical spine. All MMT measures show bilateral symmetry, and Mrs. Stevens had the following results:

- Cervical Spine: 3/5 flexion and extension; 4+/5 side flexion and rotation

- Shoulder: 3/5 flexion and abduction; 4/5 extension, adduction, external rotation and internal rotation

- Elbow: 4/5 flexion and extension

- Wrist: 4+/5 flexion, extension, radial and ulnar deviation

- Handgrip: 4-/5

- Hip: 3/5 flexion and abduction; 4-/5 extension, adduction, internal rotation and external rotation

- Knee: 4+/5 knee flexion and extension

- Ankle: 3+/5 dorsiflexion; 4+/5 plantarflexion, eversion and inversion

Neurological Scan[edit | edit source]

A neurological scan was conducted to determine if the patient has any neurological deficits from her condition such as loss of sensation, loss of motor function, change to deep tendon reflexes, and assessment of upper motor neuron lesions.

Mrs. Stevens' cervical and lumbosacral dermatomes were intact, while all myotomes were affected, likely due to muscular weakness which is characteristic of MG and RA. All upper motor neuron tests (Babinski, Hoffman, and Clonus) were negative, while lower motor neuron reflex tests (triceps, biceps, patellar, Achilles) were all normal (grade 2). The table below provides the cranial nerve test results:

| Cranial Nerves | CN V (Trigeminal) | CN VI (Abducens) | CN X (Vagus) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Result | (+) Motor

(-) Sensory |

(+) Motor (Diplopia) | (+) Motor (Dysphonia)

(-) Sensory |

Balance & Gait Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Balance: Assessed using the Berg Balance Scale. Please see below in Outcome Measures section.

- Gait Analysis: Mrs. Stevens presents with an unsteady gait; she is unable to walk in a straight line, and has slight lateral deviations, likely due to diplopia.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

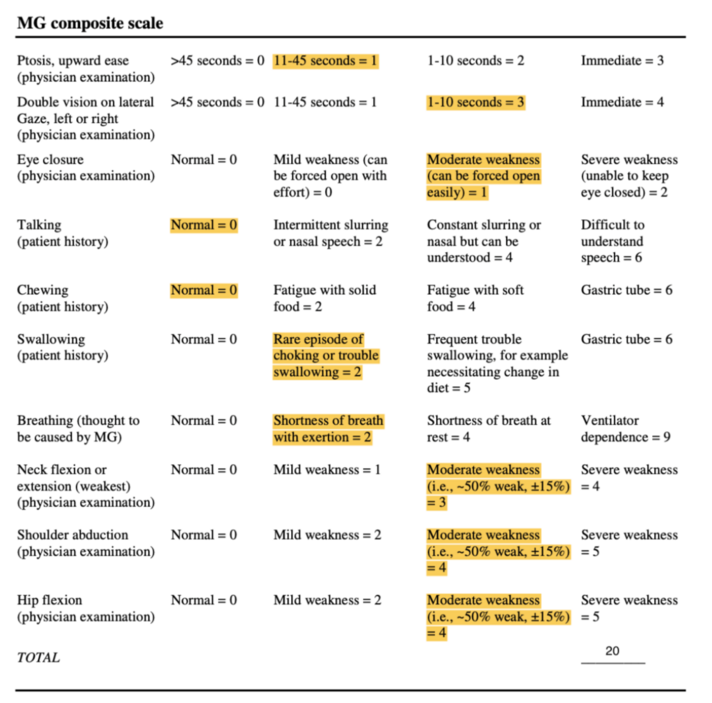

Myasthenia Gravis Composite[11][edit | edit source]

This 10-item scale measures primary signs and symptoms of MG based on physical exam and patient history[12]. Items include weakness of the ocular, neck, and proximal limb muscles, as well as patient-reported impairments in speech, chewing, swallowing, visual, and respiratory function[13]. Each item is scored on a weighted, ordinal scale, based on symptom severity[13].

Total score ranges from 0 to 50, in which higher scores indicate more severe impairment[12]. Improvement of 3-points in the total score on the MGC denotes clinically meaningful change[13].

The MGC has been found to be both a reliable and valid tool for the measurement of clinical status of MG patients, due to its excellent test-retest reliability and concurrent validity with other MG-specific measurement scales[11]. Since the MGC is simple and time efficient, it will be used to evaluate muscle strength as well as global functional impairments[14].

Mrs. Stevens scored 20/50 on the MGS. Her results are displayed in Figure 2 below:

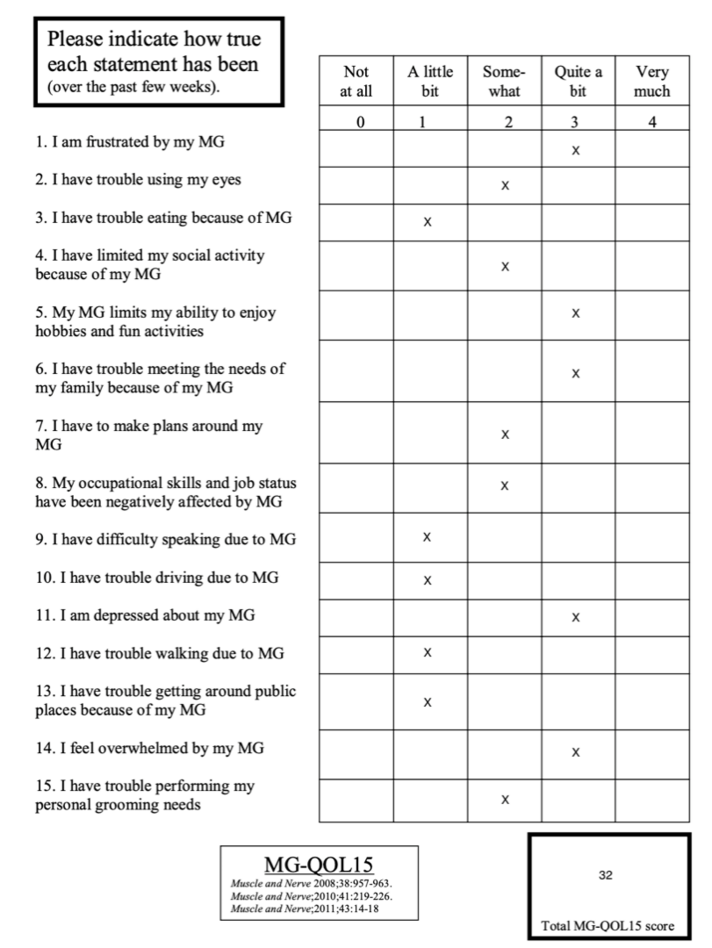

Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life[15][edit | edit source]

This 15-item, patient-reported outcome is derived from the MG-QOL60 and measures health-related quality of life, specific to the MG patient population[14]. Items are related to physical, emotional, functional and social elements, such as mobility, well-being and symptoms, and each are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4[14]. The total score ranges from 0 to 60, such that higher scores suggest poorer quality of life[14]. The MG-QOL15 has been translated and validated in numerous languages, has excellent test-retest reliability, and its scores correlate well with other MG-specific measurement tools, such as the MGC, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living measure (MG-ADL), and Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis Score (QMGS)[14].

Mrs. Stevens scored 32/60 on the MG-QOL15. Her results are displayed in Figure 3 below:

Berg Balance Scale (BBS)[edit | edit source]

The BBS is a 14-item measurement that evaluates balance in the elderly, as well as several neurological conditions[16]. The scale assesses the patient’s ability to maintain balance throughout the performance of listed tasks[17]. When a patient achieves a score less than 42 and has no history of falls, this indicates the patient is at a greater risk of future falls[17].

The BBS has high test-retest reliability and internal validity for measuring balance in neurological conditions, independent of the etiology of the balance impairment[16].

Mrs. Stevens scored 41/56 on the BBS. This indicates Mrs. Stevens has an increased risk of future falls.

Problem List[edit | edit source]

Body Structure & Function[edit | edit source]

- Impaired breathing mechanics and increased dyspnea on exertion.

- Decreased endurance presenting as weakness in proximal limb muscles.

- Impaired balance leading to an increased risk of falls.

Activity Limitations[edit | edit source]

- Decreased endurance when standing and ambulating for longer than 30 minutes without rest.

Participation Restrictions[edit | edit source]

- Reduced ability to kayak for long durations.

- Reduced ability to care for and play with her children.

Clinical Hypothesis/Impression[edit | edit source]

- Medical Diagnosis: Myasthenia Gravis - Class IIIb (see Table 1 above).

- Physiotherapy Diagnosis: Generalized fatigue which presents as bilateral muscle weakness, primarily in the proximal joints in the upper and lower extremities, affecting balance, endurance, and participation in social roles and leisure activities.

- Prognosis: Mrs. Stevens is a young, previously active woman who demonstrates high motivation to manage her symptoms and improve her quality of life, positively contributing to her prognosis. Barriers to improvement include her comorbidities of RA and hypertension, as well as familial responsibilities, which may exacerbate her fatigue. Additionally, her risk of depression may challenge her progress and impede adherence to her exercise plan. We anticipate that with regular participation in exercise, her endurance will improve to assist with symptom management and participation in meaningful activities.

Interventions[edit | edit source]

Patient-Centered Goals[edit | edit source]

Goal setting is an essential component of physiotherapy to outline a course of action for the patient and therapist to follow throughout the rehabilitation journey. Creating meaningful, patient-centered goals can enhance patient engagement, satisfaction, and adherence which will supplement recovery and improvement. Long-term and short-term goals (LTG and STG) for Mrs. Stevens will be outlined below, and were determined based off of the subjective interview and objective assessments.

- LTG1: Patient will be able to kayak for 30 minutes at a low intensity with minimal rest time within the next 2 months associated with improvements in MGC score.

- STG1: Patient will increase the repetitions of their resistance exercises before fatigue to 20 reps within 4 weeks.

- STG2: Patient will improve her MGC score from 20/60 to 15/60 by week 4.

- STG3: Patient will improve her aerobic endurance on the stationary bike to 30 minutes by 3 weeks.

- LTG2: Patient will be able to ambulate for at least 45 minutes with minimal rest before onset of fatigue within 6 weeks.

- STG3: Patient will improve her aerobic endurance on the stationary bike to 30 minutes by 3 weeks.

- LTG3: Patient will be able to engage in meaningful activities, such as grocery shopping, for 45 minutes with minimal shortness of breath within 6 weeks.

- STG4: Patient will learn and implement pursed lip breathing when she feels short of breath 50% of the time by week 2.

- STG5: Patient will use diaphragmatic breathing at rest and during activity 75% of the time by week 4.

- LTG4: Patient will be able to participate more in activities and care for her children, as a result of reduction in symptom severity, demonstrated by improvements in her MG-QOL15 score within 6 weeks.

- STG6: Patient will improve her MG-QOL15 score from 32/60 to 25/60 by week 4.

- LTG5: Patient will reduce their risk of falls demonstrated through improvements in BBS within 6 weeks.

- STG7: Patient will be able to maintain a single leg stance bilaterally for 1 minute on an uneven surface without assistance within 2 weeks.

- STG8: Patient will demonstrate an increase in her BBS from 41/56 to 45/56 within 2 months.

Approaches and Techniques[edit | edit source]

The following aerobic, resistance, and balance exercises are to be completed in one session, 2 times a week.

Aerobic Exercise[18][19][edit | edit source]

- Stationary bike: 3 minute warm up at low intensity, 5 intervals of 2 minutes at medium intensity and 1 minute at low intensity, followed by a 2 minute cool-down at low intensity

- Addresses goals: LTG1, LTG2, LTG4, STG3, and STG6

Resistance Exercise[18][19][edit | edit source]

- 2 sets, 15 reps, 2 minutes of rest time between sets

- Bilateral bicep curls using 5lbs in each arm

- Bilateral tricep extensions using 5lbs in each arm

- Bilateral shoulder press using 5lbs in each arm

- Bilateral seated cable row machine using 20lbs

- Goblet squats using a 10lbs dumbbell

- Hip abduction using a light resistance band

- Address goals: LTG1, LTG4, STG1, and STG6

Balance Exercises[18][19][edit | edit source]

- 2 sets of standing on 1 leg for 1 minute on a foam surface with eyes open, alternating between legs

- Addresses goals: LTG4, LTG5, STG6, STG7, and STG8

Breathing Exercises[20][edit | edit source]

- Diaphragmatic breathing: 10 breaths every hour

- Pursed lip breathing when patient is short of breath

- Addresses goals: LTG3, LTG4, STG2, STG4, STG5, and STG6

Patient Education[18][edit | edit source]

- Maintain moderate intensity because high intensity exercise can induce muscle weakness.

- Adequate rest between exercise and throughout the day.

- Try to complete exercises in the morning as this is likely the time of day when she feels most energized (less fatigued).

Innovative Technologies[edit | edit source]

When implementing an exercise intervention with MG patients, it is important to consider heat as a factor that can exacerbate symptoms[6][21]. In addition to performing exercise at a low intensity and taking adequate rests, cooling technology has the potential to improve muscle strength, fatigue, and respiratory function in MG patients by maintaining lower muscle temperatures when exercising[21]. Cooling technology, such as cooling garments, may allow for patients to perform exercises for prolonged periods of time prior to the onset of fatigue. During Mrs. Stevens’ in-person treatment sessions, we propose the use of the cooling garment (Personal ICE Cooling System) which consists of a network of tubes that pump cold water throughout the garment by a battery-powered pumping system[21]. This may allow for improved adherence to exercise protocols which would result in increased muscular endurance and the ability to actively participate more in meaningful activities.

Challenges:

- cost (price range from $300-$600 )

- heavy (can weigh up to 5lbs)

Regression of Exercises[edit | edit source]

If the patient reports an adverse event in response to her intervention plan, regression of her exercises can be completed as follows:

- If Mrs. Stevens finds her cycling to be too difficult, she can stay at a low intensity for the entire 20 minutes.

- If Mrs. Stevens finds she is overly fatigued after performing 2 sets of all exercises, she can regress to perform 1 set of each exercise.

- If Mrs. Stevens finds specific exercises to be difficult, she can regress them as follows:

- Bicep curl → use less weight or a resistance band

- Tricep extension → use less weight or a resistance band

- Shoulder press → use less weight

- Rows → use resistance band

- Goblet squat → bodyweight squats

- Hip abduction → bodyweight hip abduction

- If Mrs. Stevens finds the bilateral resistance exercises difficult, she can perform these exercises unilaterally.

- If Mrs. Stevens finds her balance exercises too difficult, she can move to a flat surface.

Outcome Measure Re-Assessment[edit | edit source]

The outcome re-assessment was performed three months after the referral; results can be found below.

Myasthenia Gravis Composite[edit | edit source]

Following 3 months of participating in physiotherapy, Mrs. Stevens completed the MGC again and scored 15/50. This improvement in score suggests Mrs. Stevens’ symptom severity has decreased within the past 3 months. The minimal clinically important difference for the MGC is 3 points, therefore improvement in this outcome measure reflects meaningful change in symptom severity for Mrs. Stevens[13].

Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life[edit | edit source]

Upon reassessment, Mrs. Stevens scored 24/60 on the MG-QOL15. This suggests an improvement in her quality of life related to her MG. Subjectively, she reports feeling more motivated to participate in activities, such as kayaking due to reduction in her symptoms.

Berg Balance Scale[edit | edit source]

Following 3 months of physiotherapy, Mrs. Stevens was reassessed on the BBS and scored 48/56. This change in score suggests improvements in balance, leading to a decreased risk of falling. Subjectively, Mrs. Stevens describes feeling more steady on her feet as well as increased confidence when walking.

Interdisciplinary Care Management[edit | edit source]

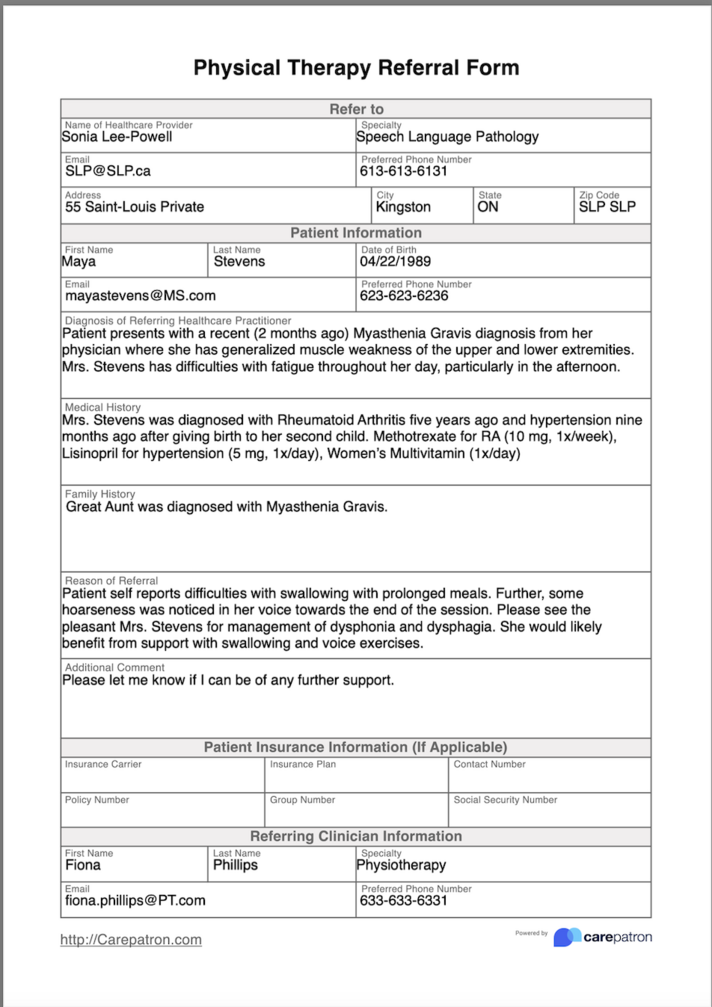

Speech Language Pathologist[edit | edit source]

A Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) can help to identify and manage the presence of issues with speaking, chewing and swallowing[22]. This may include exercises that strengthen the muscles of the throat, vocal exercises to improve voice clarity, swallowing exercises, and the timing of pharmacological interventions. The results of the MGC suggests that the patient would benefit from SLP therapy.

Occupational Therapist[edit | edit source]

An Occupational Therapist (OT) can assist with the difficulties Mrs. Stevens faces with her ADLs due to generalized muscular weakness[22]. This could include tasks that require endurance of activities like food preparation, childcare and grocery shopping. This could help Mrs. Stevens to reach her goals, including playing with and caring for her children.

Psychiatrist[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown MG to be associated with mood disorders, which puts Mrs. Stevens at a higher risk of developing depression and anxiety[23]. Therefore, it is recommended for her to have a psychiatric evaluation to address any of these factors that may be present as well as the potential prescription of medication to assist with management.

Referral Form[edit | edit source]

Discharge Planning[edit | edit source]

Mrs. Stevens will be discharged from the Physiotherapist’s caseload once she has met all of her goals and is comfortable continuing all exercises independently at home. She is encouraged to continue to monitor her symptoms and return to physiotherapy should new challenges arise.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

Myasthenia Gravis is a chronic condition, and there is currently no cure. In conjunction with other interdisciplinary health care professions, physiotherapy can help patients by providing exercise interventions and patient education. These interventions can increase patients’ endurance so that individuals with MG may enhance their participation in activities of daily living, various hobbies and social roles, leading to an overall better quality of life[18]. Physiotherapy plays an important role in the disease course management of MG and may reduce burden on patients and their families. By understanding the primary signs and symptoms of MG, as well as interventions that work best for these individuals, health care teams can provide better quality care for these patients.

Multiple Choice Questions[edit | edit source]

(1) What are the main signs and symptoms noticed in the early presentation of Myasthenia Gravis?

a) Eye drooping

b) Sensory loss

c) Loss of movement coordination

d) Muscle weakness and fatigue

e) Two of the above

f) All of the above

(2) What body functions would NOT be affected in someone diagnosed with Myasthenia Gravis?

a) Motor planning function

b) Strength

c) Breathing

d) Endurance

(3) What are the main physiotherapy interventions in Myasthenia Gravis?

a) Improve muscle endurance and strength

b) Address balance and ambulation issues

c) Education on breathing exercises

d) All of the above

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Gilhus, N.E., Nacu, A., Andersen, J.B. and Owe, J.F. Myasthenia gravis and risks for comorbidity. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22: 17-23. doi: 10.1111/ene.12599

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dresser L, Wlodarski R, Rezania K, Soliven B. Myasthenia Gravis: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021;10(11):2235–. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112235

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Gilhus N. E. Myasthenia gravis, respiratory function, and respiratory tract disease. Journal of neurology 2023; 1–12. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11733-y

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Misra, U. K., Kalita, J., Singh, V. K., & Kumar, S. A study of comorbidities in myasthenia gravis. Acta neurologica Belgica 2020; 120(1), 59–64. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01102-w

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zhi-Feng Mao, Long-Xiu Yang, Xue-An Mo, Chao Qin, Yong-Rong Lai, NingYu He, Tong Li & Maree L. Hackett. Frequency of Autoimmune Diseases in Myasthenia Gravis: A Systematic Review, International Journal of Neuroscience 2011; 121:3, 121-129. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2010.539307

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Jayam Trouth A, Dabi A, Solieman N, Kurukumbi M, Kalyanam J. Myasthenia Gravis: A Review. Autoimmune diseases. 2012;2012:874680–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/874680

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Breiner A, Widdifield J, Katzberg HD, Barnett C, Bril V, Tu K. Epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in Ontario, Canada. Neuromuscular disorders : NMD. 2016;26(1):41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2015.10.009

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Jaretzki A, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, Kaminski HJ, Keesey JC, Penn AS, et al. Myasthenia gravis : Recommendations for clinical research standards. Neurology. 2000;55(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)01595-2

- ↑ Green, Joshua D., Richard J. Barohn, Emanuela Bartoccion, Michael Benatar, Derrick Blackmore, Vinay Chaudhry, Manisha Chopra et al. "Epidemiological evidence for a hereditary contribution to myasthenia gravis: a retrospective cohort study of patients from North America." Bmj Open 10, no. 9 (2020): e037909.

- ↑ National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Manual Muscle Testing Procedures. Available from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/assets/docs/muscle_grading_and_testing_procedures_508.pdf (accessed 11 May 2023)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Burns TM, Conaway M, Sanders DB. The MG Composite: A valid and reliable outcome measure for myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1434–40. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1b1e

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Eculizumab (Soliris): Alexion Pharma Canada Corporation (CAN). Clinical Review Report: Adult patients with generalized myasthenia gravis: Appendix 5, Description and Appraisal of Outcome Measures. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2020.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567509/#:~:text=Myasthenia%20Gravis%20Activities%20of%20Daily%20Living%20Scale%20(MG%2DADL),-The%20MG%2DADL&text=Each%20of%20the%20items%20is,indicate%20greater%20severity%20of%20symptoms

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Thomsen JLS, Andersen H. Outcome Measures in Clinical Trials of Patients With Myasthenia Gravis. Frontiers in neurology. 2020;11:596382–596382. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.596382

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Barnett C, Herbelin L, Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ. Measuring Clinical Treatment Response in Myasthenia Gravis. Neurologic clinics. 2018;36(2):339–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.01.006

- ↑ Burns TM, Conaway MR, Cutter GR, Sanders DB. Less is more, or almost as much: A 15-item quality-of-life instrument for myasthenia gravis. Muscle & nerve. 2008;38(2):957–63. doi: 10.1002/mus.21053

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 La Porta F, Caselli S, Susassi S, Cavallini P, Tennant A, Franceschini M. Is the Berg Balance Scale an Internally Valid and Reliable Measure of Balance Across Different Etiologies in Neurorehabilitation? A Revisited Rasch Analysis Study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2012;93(7):1209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.020

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Berg, K., Wood-Dauphinee, S. L., Williams, J. I., & Gayton, D. (1989). Berg Balance Scale (BBS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t28729-000

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Corrado B, Giardulli B, Costa M. Evidence-based practice in rehabilitation of myasthenia gravis. A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2020 Sep 27;5(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk5040071

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Aupetitallot V, Franco AB. Effects of Physical Exercise on Functional and Respiratory Capacity, Quality of Life, and Fatigue Perception in Myasthenia Gravis Patients: A Systematic Review. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021;33(1). https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.2021037593

- ↑ Cup EH, Pieterse AJ, ten Broek-Pastoor JM, Munneke M, van Engelen BG, Hendricks HT, van der Wilt GJ, Oostendorp RA. Exercise therapy and other types of physical therapy for patients with neuromuscular diseases: a systematic review. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2007 Nov 1;88(11):1452-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.024

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Mermier CM, Schneider SM, Gurney AB, Weingart HM, Wilmerding MV. Preliminary results : Effect of whole-body cooling in patients with myasthenia gravis. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2006;38(1):13–20.doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000180887.33650.0f.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Payedimarri A babu, Ratti M, Rescinito R, Vasile A, Seys D, Dumas H, et al. Development of a Model Care Pathway for Myasthenia Gravis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(21):11591–. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111591.

- ↑ Law C, Flaherty CV, Bandyopadhyay S. A Review of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Myasthenia Gravis. Curēus (Palo Alto, CA). 2020;12(7):e9184–e9184. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9184.