Osteomyelitis

Original Editors -Nathan McCauley as part of the Bellarmine University Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Nathan McCauley, Elaine Lonnemann, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Patti Cavaleri, Kim Jackson, Daphne Jackson, WikiSysop and Rishika Babburu

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Osteomyelitis (bone infection) is an acute or chronic inflammatory process involving the bone and its structures secondary to infection (with pyogenic organisms including bacteria (mostly Staphylococcus), fungi, and mycobacteria)[1]. Acute osteomyelitis is the clinical term for a new infection in bone that can develop into a chronic reaction when intervention is delayed or inadequate.

Before the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, management of osteomyelitis was mainly surgically (eg extensive debridement, saucerization, wound packing)[1]. Since the availability of antibiotics, mortality rates from osteomyelitis, including staphylococcal osteomyelitis, has improved significantly. Despite the advances in current health care, osteomyelitis is still a major clinical challenge, with recurrent and persistent infections occurring in approximately 40% of patients[2].

The pathophysiology of osteomyelitis is complex and poorly understood. There are several key factors contributing to the infection including: the virulence of the infectious organism, the individual’s immune status, any underlying disease, and the type, location, and vascularity of the involved bone[3].

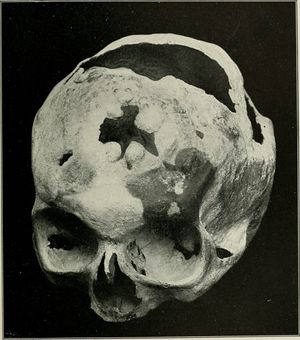

The skull image shows a case of syphilitic osteomyelitis of the skull.

Osteomyelitis is commonly divided into 3 types[4]:

- Hematogenous - originating in or spread through blood

- Secondary to contiguous infection

- Secondary to direct inoculation

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Osteomyelitis can occur for a variety of reasons and can affect all populations.

- Smokers

- People with chronic health conditions, such as diabetes or kidney failure

- People with diabetes may develop osteomyelitis in their feet if they have foot ulcers.

- Individuals with compromised immune system, such as HIV

- IV drug or alcohol abuse

- Recent injury or orthopedic surgery

- The characteristic of some bacteria to adhere to the bone and surgically implanted devices makes them resistance to antibiotic therapy and their ability to survive intracellularly may explain the persistence of bone infections and high failure rates of shorter courses of antimicrobial treatment[1]. In the case of surgery, this may lead to the need for revision surgery.

- Sickle Cell Disease[4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Osteomyelitis can occur at any age, it is common between ages of 2-12 and is more common in males

- Circulation disorders, such as peripheral arterial disease

- Problems requiring intravenous lines or catheters

- Sickle cell disease

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) can also be associated with developing osteomyelitis.

- Malnutrition

- Chronic hypoxia

- Extremes of age

Gutierrez reports that over one-half of cases of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children occur in patients younger than five years[5].

Prevalence and Incidence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of osteomyelitis has decreased throughout the years due to greater control of the spread of infection in hospitals as well as a better understanding of osteomyelitis treatment approaches. This enables the infection, in many cases, to be caught within 48 hours and prevented from becoming a chronic recurrence.

- Incidence of osteomyelitis varies widely between countries. The range has been reported to be 1.94-200 new cases per 100,000 people[4].

- A 2015 USA study reported that the incidence of osteomyelitis increased between 1969 and 2009, reasons being unclear but could comprise a variety of factors, including changes in diagnosing patterns or increases in the prevalence of risk factors (e.g., diabetes) in this population. The incidence between 1969 and 2009 and remained relatively stable among children and young adults but almost tripled among individuals older than sixty years; this was partly driven by a significant increase in diabetes-related osteomyelitis (from 2.3 cases per 100,000 person-years in the period from 1969 to 1979 to 7.6 cases per 100,000 person-years in the period from 2000 to 2009). Forty-four percent of cases involved Staphylococcus aureus infections[6].

- The incidence of osteomyelitis in children has decreased to 47/10,000 in 1990 from 87/10,000 in 1970[7].

- The incidence of vertebral osteomyelitis has been estimated at 2.4 cases per 100,000, with the risk increasing with age (0.3/100,000 among individuals <20 years of age to 6.5/100,000 among individuals >70 years of age)[8].

- The estimated incidence of Vertebral Osteomyelitis (VO) increased from 5.3/100 000 population per year in 2007 to 7.4/100 000 population per year in 2010 ( a Japanese national figure data base). They stated that "The high mortality suggests that VO remains a life-threatening disease despite advances in medical practice and should be regarded as a fatal systemic disorder rather than just a localised vertebral disorder"[9].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals presenting with osteomyelitis may have the following symptoms[10]:

- Pain and/or tenderness in the infected area (pain may not always be a factor early in the infectious process due to the lack of pain fibers in cancellous bone).

- Inflammation, redness, and warmth in the infected area

- Fever, chills, and excessive sweating

- Nausea and generalized feeling of being ill

- Lower back pain (if the vertebrae are involved and range of motion of the lumbar spine may be decreased and painful)

- Swelling of the legs, ankles, and feet

- Joint pain - if the infection extends into the periosteum of the bone, individuals may experience joint pain, decreased function, and systemic signs, such as fever, swelling, and malaise[3]

- Antalgic gait - if the infected lower extremity bone causes pain

- “Sausage toes” - a clinical sign that has been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity, may be present if osteomyelitis affects the phalanges of the feet in diabetic individuals[3].

The primary manifestations of osteomyelitis may vary between adults and children.

- In children, osteomyelitis tends to be acute, and it usually appears within 2 weeks of a pre-existing blood infection. This is known as hematogenous osteomyelitis, and it is normally due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (MRSA). They have severe complaints, such as high fever and intense pain, but in some cases the predominating symptoms are edema, erythema, and tenderness in the infected area.

- In adults, sub-acute or chronic osteomyelitis are more common, especially after an injury, surgery or trauma, such as a fractured bone. This is known as contiguous osteomyelitis. It usually affects adults over the age of 50 years

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The most common causative species are the usually commensal staphylococci, with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis responsible for the majority of cases. Staphylococcal infections are becoming an increasing global concern, partially due to the resistance mechanisms developed by staphylococci to evade the host immune system and antibiotic treatment.[2] Other organisms that cause are Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Salmonella

The image shows an exploded MRSA cyst

- Osteomyelitis can occur in a variety of bones in different areas of the body. The area affected often depends on the causative agent, the individuals’ age, and previous medical history as certain types of osteomyelitis can affect different populations.

- The bones commonly involved in children are long bones (adjacent to growth plates) such as the femur, tibia, humerus, and radius due to the amount of bone marrow present in long bones.

- Osteomyelitis in adults usually affects the vertebral column, in particular the lumbar spine, the sacrum, and the pelvis.

- Staphylococcus aureus is the usual causative agent of acute osteomyelitis. Once bound to cartilage, the organism produces a protective glycocalyx and stimulates the release of endotoxins. Other organisms such as group B streptococcus, pneumococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenza, and Escherichia coli are also capable of producing bone infection. In individuals diagnosed with sickle cell anemia, Salmonella infection can be associated with osteomyelitis[3].

- Surgical procedures, open fractures, and implanted orthotic devices are also causative agents of acute osteomyelitis. A form of osteomyelitis, exogenous osteomyelitis, occurs when bone extends out from the skin allowing a potentially infectious organism to enter from an abscess or burn, a puncture wound, or other trauma such as an open fracture. These examples of osteomyelitis secondary to infection are common in immunocompromised individuals and in those diagnosed with diabetes mellitus or severe vascular insufficiency[3].

- Hematogenous osteomyelitis is acquired from the spread of organisms from preexisting infections such that occurs in impetigo; furunculosis (persistent boils); infected lesions of varicella (chickenpox); and sinus, ear, dental, soft tissue, respiratory, and genitourinary infections. Genitourinary infections can lead to osteomyelitis of the sacrum or iliac[3].

The short video below shows a case of paediatric osteomyelitis

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Medical diagnosis is often difficult because of the lack of specific signs and symptoms, especially in chronic osteomyelitis. Signs and symptoms that are usually associated with infection may be mistaken for normal postoperative changes[3].

- May not detect bony abnormality in infections less than 10 days in duration[3].

- Lytic lesions may be demonstrable on radiographs within 2 weeks of onset of the infection[3].

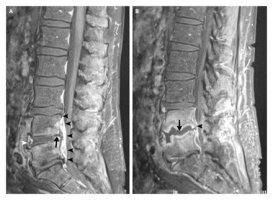

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and isotope bone scans are the procedures of choice to delineate the diseases anatomic extent[3].

- Flourine-18-flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans provide accurate localization of infection and/or source of fever of undetermined origin, thereby guiding further testing[3].

Lab Values[4]

- White blood cell count - sensitivity is low overall and varies depending on the organism causing a patient's osteomyelitis infection. If high, can indicate a severe infection.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ES) - Gigante et al reported an association has been found between an ESR value > 55 mm/h and abscess formation in a patient with pelvic osteomyelitis, whereas a value < 22 mm/h was a negative predictive factor in patients with a periosteal abscess or pyomyositis in generalized osteomyelitis[4].

- C-reactive protein - This may be the most helpful lab value for differential diagnosis of osteomyelitis. Values > 100 mg/L are more frequently associated with a complicated course and are the best predictor of the need for > 6 days of IV antibiotics[4].

Medications[edit | edit source]

A bone biopsy diagnoses what type of germ is causing the infection. An antibiotic that works well against that type of infection is then selected. The antibiotics are usually administered parentally, typically through intravenous administration. An additional course of oral antibiotics may be needed for more-serious infections. Interestingly a 2019 study on the history of osteomyelitis treatment concluded - "Although antibiotic treatment of osteomyelitis has significantly advanced over the last 80 years, standard approaches to treatment of the condition do not appear to have an extensive evidentiary basis. We find few historical data to support dictums such as the necessity of parenteral therapy, the universal necessity of giving at least 4–6 weeks of antibiotics, or the criticality of selecting antibiotics with superior “bone penetration[11].”

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Immediate treatment is indicated for osteomyelitis, especially in the acute phase. Treatment is usually initiated with an antibiotic, determined by the results of the bone biopsy or cultures taken, given intravenously at a high dose. Factors such as the patients age, health status, location of infection, and prior antimicrobial therapy are taken into consideration when determining the antibiotic used for treatment[3]. The antibiotics are usually prescribed for 4-6 weeks followed by >8 weeks of oral therapy[12].

Osteomyelitis may also need to be treated surgically. Options include:

- Draining the infected area

- Removal of necrotic bone and soft tissue

- Restoring normal blood flow to the bone

- Removing any foreign objects

- Amputation of the infected limb[13].

- Replacement of infected prostheses, such as total hip arthroplasty components

The following graphic video (2 minutes) shows a Haitian child with a severe case of osteomyelitis and management is described

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

- Physical therapists can play a vital role in the screening process for osteomyelitis. Individuals who present with signs and symptoms of possible osteomyelitis should be referred to a physician for further diagnostic testing. These signs and symptoms are included in the above sections.

- Prevention is another area in cases of osteomyelitis where physical therapists can play an important role. Chronic osteomyelitis is often a result of complication of treatment with open fractures, therefore, prevention of infection is highly important[3].

- Since the role of nutrition is vital in cases of infection, patients should be properly educated on proper nutrition in early post-surgical intervention due to the fact that most infections occur in the immediate post-operative period[3].

- Individuals who are at risk for developing osteomyelitis should be taught proper preventative measures and be aware of early warning signs that infection may be present such as, excessive pus present coming from incision line, redness, extreme tenderness, increased skin temperature near area of injury or surgical procedure, and symptoms of nausea or vomiting.

- If treated surgically for osteomyelitis, physical therapy may be indicated post-operatively to address any impairments in strength, ROM, proprioception, etc. as well as treatment for any functional limitations or disabilities secondary to the infection and surgical procedure.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following are possible conditions that could have similar signs and symptoms or relate in other ways to osteomyelitis[14]:

- Ewing Sarcoma

- Osteosarcoma

- Reactive bone marrow edema

- Traumatic or stress fractures

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Gout

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Tomaszewski D, Avella D. Vertebral osteomyelitis in a high school hockey player: a case report. J Athl Train 1999;34(1):29-33.

Kline A. Streptococcal Group-B Osteomyelitis of the foot: a case report. Podiatry Internet Journal 2007;2(1):3.

Resources[edit | edit source]

The Journal of the American Medical Association. Osteomyelitis

National Institue of Health. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). [1]

The Nemours Foundation. Teens Health. [2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Momodu II, Savaliya V. Osteomyelitis. InStatPearls [Internet] 2018 Oct 14. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532250/ (last accessed 5.10.19)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kavanagh N, Ryan EJ, Widaa A, Sexton G, Fennell J, O'Rourke S, Cahill KC, Kearney CJ, O'Brien FJ, Kerrigan SW. Staphylococcal osteomyelitis: disease progression, treatment challenges, and future directions. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2018 Apr 1;31(2):e00084-17. Available from: https://cmr.asm.org/content/31/2/e00084-17 (last accessed 5.10.19)

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Gigante A, Coppa V, Marinelli M, Giampaolini N, Falcioni D, Specchia N. Acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019 Apr;23(2 Suppl):145-158.

- ↑ Gutierrez K. Bone and joint infections in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005 Jun;52(3):779-94, vi.

- ↑ Kremers, H.M., Nwojo, M.E., Ransom, J.E., Wood-Wentz, C.M., Melton III, L.J. and Huddleston III, P.M., 2015. Trends in the epidemiology of osteomyelitis: a population-based study, 1969 to 2009. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 97(10), p.837. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4642868/ (last accessed 5.10.19)

- ↑ Craigen MA, Watters J, Hackett JS. The changing epidemiology of osteomyelitis in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1992;74B(4):541-545

- ↑ Zimmerli W. Vertebral osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1022-1029.

- ↑ Akiyama T, Chikuda H, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Saita K. Incidence and risk factors for mortality of vertebral osteomyelitis: a retrospective analysis using the Japanese diagnosis procedure combination database. BMJ open. 2013 Jan 1;3(3):e002412. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/3/e002412 (last accessed 5.10.19)

- ↑ The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Staff. Osteomyelitis. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. http://my.clevelandclinic.org/disorders/osteomyelitis/hic_osteomyelitis.aspx. Accessed March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Nicolás W Cortés-Penfield, Prathit A Kulkarni, The History of Antibiotic Treatment of Osteomyelitis, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 6, Issue 5, May 2019, ofz181, Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz181 (last accessed 5.10.19)

- ↑ Nuermberger E. Osteomyelitis, chronic. John Hopkins Plan of Care Information Technology 2009. http://hopkins-abxguide.org/diagnosis/bone_joint/osteomyelitis/full_osteomyelitis__chronic.html (accessed 17 March 2011).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic staff. Osteomyelitis. The Mayo Clinic. 2010. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/osteomyelitis/DS00759 (accessed 6 April 2011).

- ↑ Willis K. Osteomyelitis. Stanford University Medical Media and Information Technologies 2003. http://osteomyelitis.stanford.edu/pages/main.html (accessed 3 April 2011).