SLAP Lesion

Original Editor - Kristin Sartore, Venugopal Pawar

Top Contributors - Venugopal Pawar, Lucinda hampton, Fasuba Ayobami, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Amrita Patro, Wanda van Niekerk, Vasileios Tyros and Admin

Introduction[edit | edit source]

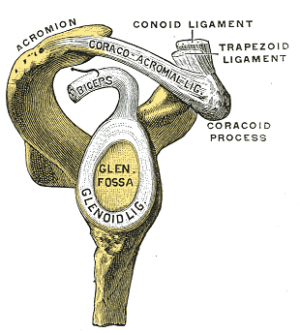

Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) tears are injuries of the glenoid labrum. They involve the superior glenoid labrum, where the long head of biceps tendon inserts. They may extend into the tendon, involve the glenohumeral ligaments or extend into other quadrants of the labrum. Unlike Bankart lesions and anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA) lesions, they are not usually (20%) associated with shoulder instability.[1]

Four types of SLAP lesions involving the biceps anchor are identified:

- Degenerative fraying with no detachment of the biceps insertion.

- Detachment of the superior labrum and biceps from the glenoid rim. Most common. In younger patients (<40 years of age) these are associated with Bankart lesions and in older patients (>40 years of age) they are seen with rotator cuff tears.[1]

- Bucket-handle tear of the labrum with an intact biceps tendon insertion to the bone.

- Intra-substance tear of the biceps tendon with a bucket-handle tear of the superior aspect of the labrum. Least common .[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that SLAP tears account for 80% to 90% of labral pathology in the stable shoulder, however they are usually seen in association with other shoulder pathologies and rarely in isolation. SLAP tears account for approximately 1% to 3% of injuries in sports medicine centres and approximately 6% of shoulder arthroscopy procedures show SLAP tears.[3]

- Age variations: From the average age of 35, the superior labrum is less firmly attached to the glenoid than in people under the age of 30. There is an age-related effect in which the older the patient is, the more likely he will incur a SLAP lesion, due to age-related changes of the labrum.[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

In the acute setting, SLAP injuries are most frequently seen in falls onto an outstretched arm. In this situation the shoulder is abducted and slightly forward-flexed at the time of the impact. Other mechanisms of injury include:

- Repetitive throwing, Throwers can have repetitive microtraumata. At the moment of the impact the glenohumeral contact point is shifted posterosuperiorly and increased shear forces are placed on the posterior-superior labrum, which results in a peel-back effect and eventually in a SLAP lesion.[5]

- Hyperextension,

- Heavy lifting,

- Direct trauma.[5]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most common complaint in patients that present with SLAP lesions is pain. Pain is typically intermittent and often associated with overhead movements.[6]Isolated SLAP lesions are uncommon.[7]The majority of patients with SLAP lesions will also complain of:

- sensations of painful clicking and/or popping with shoulder movement

- loss of glenohumeral internal rotation range of motion

- pain with overhead motions

- loss of rotator cuff muscular strength and endurance

- loss of scapular stabiliser muscle strength and endurance

- inability to lie on the affected shoulder[8]

Athletes performing overhead movements, especially pitchers, may develop “dead arm” syndrome in which they have a painful shoulder with throwing and can no longer throw with pre-injury velocity.[9]They may also report a loss of velocity and accuracy along with discomfort in the shoulder.[8]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Begins with inspection of the involved extremity, noting muscle bulk, atrophy etc. Next inspect the affected shoulder and compared to the unaffected side. Check bilateral passive and active range of motion, noting any motion that elicits pain (frequently seen with passive external rotation at 90° of shoulder abduction). Overhead athletes may have excessive external rotation with posterior capsule tightness and reduced internal rotation. Motor strength is next tested, noting rotator cuff pathology or shoulder instability. Specific diagnostic maneuvers for SLAP lesions are shown below in diagnosis.[10]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

SLAP lesions are difficult to diagnose as they are very similar to those of instability and rotator cuff disorders. MR arthrogram: The investigation of choice is an MR arthrogram, which is variably reported as having accuracies of 75-90%, although distinguishing between subtypes can be difficult.[11]

The physical examination: A combination of two sensitive tests and one specific test is useful to diagnose a SLAP lesion[8].

- Sensitive tests include: Compression rotation test; O’Briens test; Apprehension Test

- Specific tests include: Speed’s test; Yergason’s test; Biceps load test II[8][12]

If one of the three tests is positive, this will result in a sensitivity of about 75%. But if all three tests are positive this will result in a specificity of about 90%.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

See Category:Shoulder - Outcome Measures This measure is a useful example Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC) Index

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The differential diagnosis for chronic shoulder pain includes many etiologies:

- Impingement: eg Subcoracoid, Calcific tendonitis.

- Rotator Cuff pathology

- Degenerative pathology

- Proximal Biceps pathology eg subluxation, tendonitis.[3]

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

For the vast majority of SLAP injuries, the initial management is nonoperative. Nonoperative management modalities include: Anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy/cooling/ice application, rest and activity modification

- Type I tears: Commonly asymptomatic and do not require treatment

- Type II tears: Need surgical reattachment

- Type III tears: Normally need resection of the bucket handle tear[1]

If non-operative treatment modalities fail, operative management is considered, while keeping in mind each patient’s age, concomitant pathologies, functional requirements, occupational demands, and sport-specific goals.[3]

This 2 minute video shows SLAP Repair Arthroscopic Double loaded anchor Y config. Ideal graphic animation, using Antero-Sup portal avoiding rotator cuff portal.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative Management: A small subset of patients, for example those with type I SLAP lesions, can try conservative treatment. Initially this involves cessation of throwing activities, followed by a short course of anti-inflammatory medication aimed at reducing pain and inflammation. When the pain has subsided, physical therapy focuses on restoring normal shoulder motion. Strengthening of the shoulder girdle musculature is critical for normal shoulder bomechanics.[10]

Postoperative Rehabilitation (following SLAP repair) varies according to the type of SLAP lesion, the surgical procedure performed (debridement versus repair), and any other shoulder pathology. Usually the patient's shoulder is immobilised for a short period, followed by restoring motion and, lastly, commencing strengthening exercises. What follows is an example of a postoperative guidelines for patients who have had a SLAP repair with no associated pathology.

- Week 0 to 3 weeks postoperatively: Patient's shoulder is immobilized in internal rotation in a sling. Client not allowed any external rotation and abduction is limited to 60°. Pendulum and elbow range-of-motion exercise are performed.

- Week 4-8 weeks: Sling use stopped, shoulder motion is increased using active-assisted and passive techniques. limited external rotation to 30° to minimize strain on the labrum. Internal rotation and external rotation range-of-motion activities are progressed to 90° of shoulder abduction.

- Week 8 week: Initiate resistance exercises, focusing on scapular strengthening, provided adequate motion has been achieved Approximately 115° to 120° of shoulder external rotation must be achieved before starting scapular strengthening. Resisted biceps activity (elbow flexion and forearm supination) prohibited for 2 months to protect the healing of the biceps anchor.

- Week 16: Sport-directed throwing program can commence in overhead athletes. See details below.

- Week 24 : Contact sports are generally[10]

Week 16: Sport-directed throwing program. Exercises can be chosen on the basis of several EMG studies and clinical recommendations regarding the rehabilitation of patients with SLAP lesions.

These exercises are:

- forward flexion in a side-lying position

- prone extension

- seated rowing

- serratus punch (protraction with the elbow extended)

- knee push-up plus

- forward flexion in external rotation and forearm supination

- full can (elevation in the scapular plane in external rotation

- internal rotation in 20° of abduction

- external rotation in 20° of abduction

- internal rotation in 90° of abduction

- external rotation in 90° of abduction

- forearm supination, elbow flexion in forearm supination

- uppercut (combined forward flexion of the shoulder and flexion and supination of the elbow)

- internal rotation diagonal

- external rotation diagonal

These exercises, with increasing low to moderate activity, can be applied in the early and intermediate phases of nonoperative and postoperative treatment for patients with proximal biceps tendon disorders and SLAP lesions.[13]

SLAP lesion repair often fails, and biceps tenodesis or tenotomy seems to be an acceptable alternative treatment for SLAP lesions. Furthermore, this technique has now become the most preferable treatment for failed SLAP repairs.[14]The indications for biceps tenodesis as the index procedure for a symptomatic SLAP lesion depends on:

- the patient’s age

- activity level

- arm dominance

- type of sport.[7]

If a biceps tenodesis is performed a minimum of 10 weeks is recommended without biceps activity to allow the repaired soft tissue to fully incorporate into the bone tunnels.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Radiopedia Superior labral anterior posterior tear Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/superior-labral-anterior-posterior-tear (accessed 23.8.2022)

- ↑ CHRISTOPHER C. et al., SLAP Lesions: An Update on Recognition and Treatment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2009; 39(2):71-80

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Varacallo M, Tapscott DC, Mair SD. Superior labrum anterior posterior lesions.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538284/ (accessed 23.8.2022)

- ↑ KOZIAK A. et al, Magnetic resonance arthrography assessment of the superior labrum using the BLC system: age-related changes mimicking SLAP-2 lesions. Skeletal Radiology, 2014;43: 1065 – 1070

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 POWELL S.E. et al., The Diagnosis, Classification, and Treatment of SLAP Lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med, 2012;20 (1):46 – 56

- ↑ WILK K.E. et al, The recognition and treatment of superior labral (SLAP) lesions in the overhead athlete. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther., 2013; 8(5): 579-600

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 HURI G. et al, Treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a literature review. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc., 2014;48(3): 290-297

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 MANSKE R. et al., Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) rehabilitation in the overhead athlete. Phys Ther Sport., 2010;110-121

- ↑ KNESEK M. et al., Diagnosis and management of superior labral anterior posterior tears in throwing athlets. Am. J. Sports Med, 2013;41:444-460

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Dodson CC, Altchek DW. SLAP lesions: an update on recognition and treatment. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2009 Feb;39(2):71-80.Available:https://www.jospt.org/doi/full/10.2519/jospt.2009.2850#_i49 (accessed 11.1.2023)

- ↑ GASKILL T.R., The rotator interval: pathology and management, Journal of Arthroscopy and Related Surgery 2011, vol. 27, issue 4, p. 556-567

- ↑ OH, J. H. et al., The evaluation of various physical examinations for the diagnosis of type II superior labrum anterior and posterior lesion. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2008;36:353-359

- ↑ COOLS A .M. et al., Rehabilitation Exercises for Athletes With Biceps Disorders and SLAP Lesions: A Continuum of Exercises With Increasing Loads on the Biceps. Am J Sports Med.,2014 ;42(6):1315-1322

- ↑ WEBER S.C., Surgical management of the failed SLAP repair. Sports Med Arthrosc.,2010;18:162-166