Spondylolysis

Original Editors - Dejonckheere Margo Andrea Nees Elien VanderlindenHeleen Van CleynenbreugelEls Van haver as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project.

Top Contributors - Els Van Haver, Rani Vetsuypens, Abbey Wright, Admin, Melissa Coetsee, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, James Greenwood, Dejonckheere Margo, WikiSysop and Kim Jackson -

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis is a unilateral or bilateral bony defect in the pars interarticularis or isthmus of the vertebra. It most commonly affects the lumbar vertebrae, but has also been reported in the cervical and thoracic region[1]. The term derives from the Greek words spondylos (vertebra) and lysis (defect). [2] It can cause a slipping of the vertebra, in which case the term spondylolytic spondylolysthesis is used.

Follow this link for more on Thoracic Spondylolysis

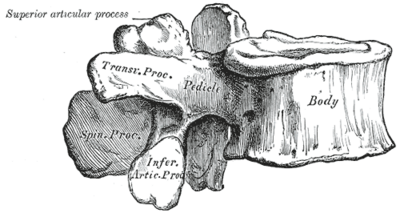

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Vertebrae consist of the vertebral body and a bony ring or arcus which protects the spinal cord. The arcus is formed by two pedicles which attach to the dorsal side of the vertebral body and two laminae, which complete the arch. The area between the pedicle and the lamina is called the pars interarticularis and is in fact the weakest part of the arcus. It is the pars interarticularis that is affected in spondylolysis.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis affects 6-8% of the general population.[3]This condition usually appears in the first or second decade of life; the frequency of spondylolysis increases with age until 20 years.[4] There is, however, no change in prevalence with increasing age from 20 to 80 years old. Men are affected twice as often as women.[5]There is a possible genetic tendency for people with lower cortical bone density at the pars interarticularis.[6] There is increased prevalence in specific ethnic, sports and family groups, with particular increased frequency in young athletic population[3]. There is an increased risk in gymnasts, football players, cricketers, swimmers, divers, weight lifters and wrestlers.

More information regarding spondylolysis in the young athletic population can be found on these pages:

Spondylolysis is considered to be a stress fracture that results from mechanical stress at the pars interarticularis. These stress fractures most often occur due to repetitive load and stress, rather than being caused by a single traumatic event.[6] The stress distribution at the pars interarticularis at its highest in extension and rotation movements.[6]Spondylolysis occurs mostly at L5 (80-95%).

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Majority of the cases are asymptomatic. Incidental findings of spondylolysis in a asymptomatic individual should not warrant treatment[7].

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Specific symptoms depend on the region of the spine that is affected[7]:

- Can be acute or gradual onset of pain

- Possible history of local trauma (recent or historical)

- Pain worsens with activity

- Rest usually relieves the symptoms

- Lumbar symptoms include:

- Focal low bac pain - radiating pain to the legs is uncommon

- Symptoms increase with lumbar extension/rotation

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spine:

The most common findings for lumbar spondylolysis are hyperlordotic posture and low back pain during lumbar extension.[8] Neurologic exam is usually normal but neurogenic symptoms can arise if the condition progresses to spondylolisthesis.

For more Objective findings in the Lumbar spine, see Spondylolysis in Young Athletes

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Disc Injuries: Disc Herniation

- Lumbosacral Discogenic Pain Syndrome

- Facet Joint Syndrome

- Acute Bony Injuries

- Sprain/Strain Injuries

- Spondylosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Myofascial Pain in Athletes

- Sacroiliac Joint Injury

- Lumbar radiculopathy

- Osteoid osteoma

- Osteomyelitis

- Spinal stenosis

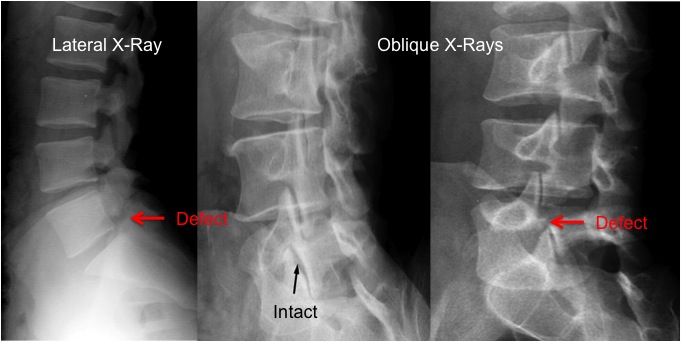

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Definitive diagnosis can be a challenge as clinical tests have little value and the he most appropriate form of diagnostic imaging has not yet been clearly established.[7]

Diagnostic Imaging[edit | edit source]

CT scans, SPECT scans and MRI have all been found to be sensitive diagnostic tools for spondylolysis. It is however important to consider the amount of radiation exposure in adolescents. For more information on diagnostic imaging visit Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport.

One-Legged Extension Test[edit | edit source]

Research has found that the one-legged hyperextension manoeuvre was neither specific nor sensitive in detecting spondylolysis. The manoeuvre may detect an abnormality in the posterior structures but should not be relied upon to make the diagnosis[3].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire

- Oswestry Disability Index

- Micheli Functional Scale - most appropriate for higher functioning populations

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Conservative Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment is usually sufficient to treat symptomatic spondylolysis and aims to reduce pain and facilitate healing processes.[7]

Possible features of conservative treatment are:[3][7]

- NSAIDs to provide pain relief

- Rest - Cessation of aggravating (sporting) activities

- The use of a spinal brace to prevent motion at the injured pars and allow bony repair

- Further research is necessary to establish its effectiveness - until then it may be recommended in cases that fail to improve with rest alone

- Physiotherapy

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

When severe pain is persistent despite conservative management and/or progression to spondylolisthesis needs to be prevented surgical treatment may be warranted. This only occurs in some patients and evidence of long-term benefit is still uncertain. Latest procedures attempt a repair of the affected pars with preservation of the segmental mobility whereas earlier methods sometimes included a spinal fusion procedure.[10][11]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Goals of Treatment[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy in spondylolysis has multiple goals:[12] [11]

- Facilitating the healing processes by promoting additional blood flow and thus healing of the affected pars. This can be accomplished by isometric contractions of the surrounding muscles.

- Avoiding aggravation or chronicity by addressing underlying causes (e.g. hypermobility, hyperextension in specific sports, weakness or lack of mobility in other body parts, psychosocial factors)

- Optimization of physical function

- Global and specific strengthening exercises

- Reducing pain

- Promoting normal movement patterns

Aspects of Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

A rehabilitation program should included the following aspects: [8] [11]

- Control pain and inflammation: Taking stress off the injured area allows physiological healing processes to take place. Therefore, it may be necessary to avoid rotational shearing forces and extension movements with a temporary cessation of sporting activities and/or wearing a brace. It reduces the pain intensity and functional disability levels. [8] [11]

- Strength and flexibility: As paraspinal muscle spasms and hamstrings tightness are often seen in patients with spondylolysis, stretching exercises can be added to the rehabilitation program. [13] [11] [8] A global strengthening program should be started which can include specific back strengthening exercises.[7]

- Stabilisation: Neuromuscular stabilisation techniques, including activation of transversus abdominis and other core stabilizer muscles have be shown to decrease pain[7].

- Functional movement: The main goal of physiotherapy is to increase functional abilities through a home exercise program. As soon as primary pain decreases, patients have to be encouraged to resume activities as tolerated[7]. Rehabilitation needs to include functional or sport-specific strengthening

For more detail on core strengthening see Core Strengthening and the PGM Method. For a detailed approach to rehabilitation for young patients with lumbar spondylolysis, read this article

Biopsychosocial Approach[edit | edit source]

Pain is a multidimensional phenomenon, and although spondylolysis has a clear 'biological' element (stress fracture), many patients are asymptomatic. This again emphasises that various different factors are involved in the experience of pain. Some factors to consider when managing a patient who presents with symptomatic spondylolysis[7]:

- Athletes: Time off sport can results in fear, low self-esteem and frustration. Communication with coaches and recovery estimates can be very helpful. Finding alternative ways to maintain cardiovascular fitness can provide a positive focus for worried athletes.

- Mental Health: Especially important to assess in patients with long-standing pain. Emotional stress, anxiety and depression may influence pain and needs to be considered. Offering positive emotional support, active listening and goal setting can help improve psychological factors.

- Fear-Avoidance and Communication: The use of words such, as 'broken spine' can instil fear in patients and negatively affect pain and participation in rehabilitation. Non-threatening communication and reassurance relating to positive outcomes/prognosis is vital.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis is a relatively common condition, especially in athletes, but is not always symptomatic. In symptomatic cases, a biopsychosocial, evidence based approach is imperative:

- Bio: Early diagnosis and adequate rest is important to aid recovery. Specific lumbopelvic strengthening has been shown to provide benefits. Surgery is only reserved for cases that do not respond to comprehensive conservative management

- Psycho: Fear of movement and mental health aspects need to be addressed

- Social: Participation in daily activities and sport should be resumed as soon as possible. Sport-specific rehabilitation plays a key role in athletes

For more on this topic also see:

Lumbar Spondylolysis in Extension Related Sport

Spondylolysis in Young Athletes

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ramachandran K, Viswanathan VK, Kavishwar RA, Shetty AP, Shanmuganathan R. Spondylolysis of the Thoracic Spine with Instability: A Rare Cause for Myelopathy. JBJS Case Connector. 2022 Jan 1;12(1):e21.

- ↑ Gunzburg R., Szpalski M., Spondylolysis, Spondylolisthesis and Degenerative Spondylolisthesis, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Debnath UK. Lumbar spondylolysis-Current concepts review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2021 Oct 1;21:101535.

- ↑ Fast A., Goldsher D., Navigating The Adult Spine, Demos Medical Publishing, 2007, p. 55.

- ↑ MacAuley D., Best T., Evidence-based Sports Medicine, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 282.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Haun DW, Kettner NW. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a narrative review of etiology, diagnosis, and conservative management. Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2005 Dec 1;4(4):206-17.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Selhorst M, Allen M, McHugh R, MacDonald J. Rehabilitation considerations for spondylolysis in the youth athlete. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2020 Apr;15(2):287.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Leone A, Cianfoni A, Cerase A, Magarelli N, Bonomo L. Lumbar spondylolysis: a review. Skeletal radiology. 2011 Jun 1;40(6):683-700.

- ↑ CRTechnologies One-Leg Standing Lumbar Extension Test (CR) Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V59XhIqedHg [Last accessed 13/08/2011]

- ↑ Cavalier R, Herman MJ, Cheung EV, Pizzutillo PD. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents: I. Diagnosis, natural history, and nonsurgical management. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2006 Jul 1;14(7):417-24.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Manual therapy. 2003 May 1;8(2):80-91.

- ↑ Standaert CJ, Herring SA. Spondylolysis: a critical review. British journal of sports medicine. 2000 Dec 1;34(6):415-22.

- ↑ Garet M, Reiman MP, Mathers J, Sylvain J. Nonoperative treatment in lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a systematic review. Sports health. 2013 May;5(3):225-32.