Emotional and Psychological Reactions to Amputation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Many of the psychological reactions may be transient, some are helpful and constructive, others less so, and a few may require further action (e.g. psychiatric assessment in the case of psychosis)<ref name=":0" />. | Many of the psychological reactions may be transient, some are helpful and constructive, others less so, and a few may require further action (e.g. psychiatric assessment in the case of psychosis)<ref name=":0" />. | ||

About 30% of amputees are troubled by depression<ref name=":0" />. Psychological morbidity, decreased self esteem, distorted body image, increased dependency and significant levels of social isolation are also observed in short and long-term follow up after amputation<ref>Thompson D M, Haran D 1983 Living with an amputation: the patient. International Rehabilitation Medicine 5:165–169</ref><ref>Srivastava, K., Saldanha, D., Chaudhury, S., Ryali, V., Goyal, S., Bhattacharyya, D. and Basannar, D. (2010). A Study of Psychological Correlates after Amputation. ''Medical Journal Armed Forces India'', 66(4), pp.367-373.</ref>. | About 30% of amputees are troubled by [[depression]]<ref name=":0" />. Psychological morbidity, decreased self esteem, distorted body image, increased dependency and significant levels of social isolation are also observed in short and long-term follow up after amputation<ref>Thompson D M, Haran D 1983 Living with an amputation: the patient. International Rehabilitation Medicine 5:165–169</ref><ref>Srivastava, K., Saldanha, D., Chaudhury, S., Ryali, V., Goyal, S., Bhattacharyya, D. and Basannar, D. (2010). A Study of Psychological Correlates after Amputation. ''Medical Journal Armed Forces India'', 66(4), pp.367-373.</ref>. | ||

== Psychological Reactions to Amputation == | == Psychological Reactions to Amputation == | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Cosmetic appearance appears to play as great a role in psychological sequelae of amputation.Body image, defined as ‘the individual’s psycho-logical picture of himself’<ref name=":2">Henker III, F. (1979). Body-image conffict following trauma and surgery. ''Psychosomatics'', 20(12), pp.812-820.</ref> is disrupted when a limb is amputated<ref name=":0" />. A number of of body image-related problems may be frequently experienced following amputation such as anxiety and sexual impairment and/or dysfunction<ref name=":2" /> (77% in males and 38% in females)<ref name=":0" />. | Cosmetic appearance appears to play as great a role in psychological sequelae of amputation.Body image, defined as ‘the individual’s psycho-logical picture of himself’<ref name=":2">Henker III, F. (1979). Body-image conffict following trauma and surgery. ''Psychosomatics'', 20(12), pp.812-820.</ref> is disrupted when a limb is amputated<ref name=":0" />. A number of of body image-related problems may be frequently experienced following amputation such as anxiety and sexual impairment and/or dysfunction<ref name=":2" /> (77% in males and 38% in females)<ref name=":0" />. | ||

[[File:Life goes on.jpg|thumb|250x250px]] | |||

The reaction to amputation may not always be negative. When amputations occur after a long period of illness and loss of function, the patient may already have gone through a period of grieving and have no need to grieve again for the amputation<ref name=":0" />. | The reaction to amputation may not always be negative. When amputations occur after a long period of illness and loss of function, the patient may already have gone through a period of grieving and have no need to grieve again for the amputation<ref name=":0" />. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

In the same study, 46% considered that something good had happened as a result of the amputation. Participants stated many reasons as good things that happened following amputation such as: the Independence given to them by the amputation and the prosthesis, subsequent change in their attitude of life, improved coping abilities, financial benefits, elimination of pain and that amputation was a character building for some of them. Furthermore, finding positive meaning was significantly associated with more favorable physical capabilities and health ratings, lower levels of Athletic Activity Restriction and higher levels of Adjustment to Limitation<ref name=":3" />. | In the same study, 46% considered that something good had happened as a result of the amputation. Participants stated many reasons as good things that happened following amputation such as: the Independence given to them by the amputation and the prosthesis, subsequent change in their attitude of life, improved coping abilities, financial benefits, elimination of pain and that amputation was a character building for some of them. Furthermore, finding positive meaning was significantly associated with more favorable physical capabilities and health ratings, lower levels of Athletic Activity Restriction and higher levels of Adjustment to Limitation<ref name=":3" />. | ||

== | === '''Coping Styles''' === | ||

[[File:Five stages of grief.jpeg|thumb|512x512px]] | |||

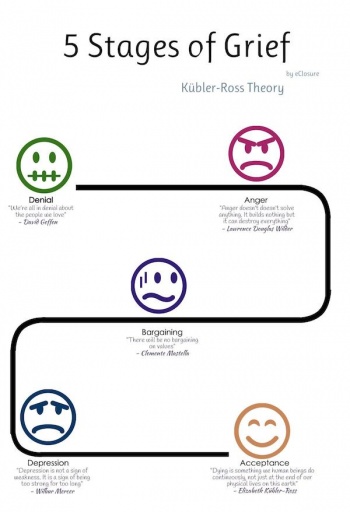

When there is time to think about impending loss, classic '''stages of grie'''f may be experienced<ref name=":1" /><ref>PARKES, C. (1975). Psycho-social Transitions: Comparison between Reactions to Loss of a Limb and Loss of a Spouse. ''The British Journal of Psychiatry'', 127(3), pp.204-210.</ref>: | |||

* Denial; often manifest as refusal to engage in discussion or to ask basic questions about the planned procedure | |||

* Anger: which may be directed towards the medical team, with expressions of being cheated or tricked into agreeing to an amputation | |||

* Bargaining: by attempting to forestall the surgery or to delay it indefinitely for a myriad of reasons such as ‘’I’m too tired I don’t want to go through with any major surgery’’ | |||

* Depression: taking the form of learned helplessness’’ feeling of passivity, and being overwhelmed | |||

* Acceptance: which may not be reached until the patient is into the rehabilitation process. | |||

A minority of amputees experience denial in relation to accepting their impairment (i.e. the reality that their limb is missing). However, phantom sensation may play a role in reinforcing the denial. This degree of denial may lead to serious problems. Such a disconnection with reality may indicate some underlying psychosis and if this state persists for more than a few days and the amputee is not responding to counseling, a psychiatric assessment should be requested<ref name=":0" />. | |||

'''Maladaptive coping styles''' can be classified as overcompensation, surrender, or avoidance. <sup>44</sup> Overcompensation can take the form of hostility, excessive self-assertion (e.g., by refusing help that is needed), recognition seeking, manipulation, or obsessiveness (e.g., by becoming preoccupied with smaller details of care at the expense of regaining whatever enjoyment of life is still possible). Surrender may take the form of clinging to the sick role and continuing to demand a high level of nursing care, while refusing to undergo rehabilitation. Avoidance may result in psychological withdrawal, addictive self-soothing, or social withdrawal<ref name=":1" />. | |||

'''Mutilation anxiety''' is closely related to one's coping style and to the experience of pain. Prior to amputation, as part of the course of prevention (of both chronic vascular disease, as well as accidental injury), mutilation anxiety can be used to motivate patients for self-care and medical compliance. After amputation, mutilation anxiety may be a factor in referring a patient for psychotherapy or treatment of anxiety with medications. Mutilation anxiety may also affect the sexual function of a patient<ref>Shell, J. and Miller, M. (1999). The Cancer Amputee and Sexuality. ''Orthopaedic Nursing'', 18(5), pp.53???64.</ref>. Men have reported feeling castrated by amputation, while women are more likely to report feeling sexual guilt and “punished” for some real or imagined transgression by amputation<ref>Hogan, R. (1985). ''Human sexuality''. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton-Century-Crofts.</ref>. Medical management of fatigue, pain, and cosmesis of the stump can further alleviate these difficulties during the rehabilitation process<ref name=":1" />. | |||

In contrast, some amputees adapt '''effective coping styles that''' result from self-efficacy, using humor, making plans and visualizing the future, and actively seeking help to solve problems. [http://www.selfcareinsocialwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WAYS-OF-COPING-was-designed-by-Lazarus-and-Folkman.pdf The Way of Coping Check-List] can be used to screen for patients at high risk for adjusting poorly to amputation and for having further negative sequelae. | |||

== Sub Heading 3<br> == | == Sub Heading 3<br> == | ||

Revision as of 15:10, 29 March 2018

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

Aim:

- To enable the reader to be aware of the common emotional and psychological reactions to amputation and demonstrate an understanding of the stages of the grieving process (may ned to create another separate page for the grieving process)

A quick word on content:

Content criteria:

- Evidence based

- Referenced

- Include images and videos

- Include a list of open online resources that we can link to

Example content:

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Mariam Hashem, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Kim Jackson, Lauren Lopez, Admin, Tarina van der Stockt, Amanda Ager, Jess Bell, Jorge Rodríguez Palomino and Claire Knott

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Amputation proposes multi-directional challenges. It affects function, sensation and body image. The psychological reactions vary greatly and depend on many factors and variable. In most cases, the predominant experience of the amputee is one of loss: not only the obvious loss of the limb, but also resulting losses in function, self-image, career and relationships[1].

Many of the psychological reactions may be transient, some are helpful and constructive, others less so, and a few may require further action (e.g. psychiatric assessment in the case of psychosis)[1].

About 30% of amputees are troubled by depression[1]. Psychological morbidity, decreased self esteem, distorted body image, increased dependency and significant levels of social isolation are also observed in short and long-term follow up after amputation[2][3].

Psychological Reactions to Amputation[edit | edit source]

Immediate reaction to the news of amputation depends on whether the amputation was planned, occurred within the context of chronic medical illness or necessitated by a sudden onset of infection or trauma[4].

After learning that amputation may be required, anxiety often alternates with depression. This anxiety may be generalized (e.g., manifest by jitteriness, a decreased ability to sleep, silent rumination, and social withdrawal) or result in disturbed sleep and irritability. Anxiety may be directed toward the fate of the limb that will be removed[5], as well as about the prospect of phantom limb pain, which many patients (who know of other amputees) may be familiar with[4]. Findings by Parkes [17] also found that in first year 25% amputees suffer from depression, feeling of insecurity, self consciousness and restlessness18].

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appears to be more common in amputees following combat, accidental injury, burn and suicidal attempts[6].In contrast, PTSD is relatively rare (< 5%) among amputees whose surgery follows a chronic illness[7].

Cosmetic appearance appears to play as great a role in psychological sequelae of amputation.Body image, defined as ‘the individual’s psycho-logical picture of himself’[8] is disrupted when a limb is amputated[1]. A number of of body image-related problems may be frequently experienced following amputation such as anxiety and sexual impairment and/or dysfunction[8] (77% in males and 38% in females)[1].

The reaction to amputation may not always be negative. When amputations occur after a long period of illness and loss of function, the patient may already have gone through a period of grieving and have no need to grieve again for the amputation[1].

A study[9] that investigated positive thoughts in amputation showed that 56% of people thought about their amputated limb. People with bilateral or a trans-femoral amputation were more likely to think about their amputated limb than people with a trans-tibial amputation. This may refer to the fact that the more of a limb that is lost the greater is the difficultly in restoring physical functioning. Thinking about the amputated limb may arise questions (e.g. what happened to the amputated limb? What life would have been like if they had not lost a limb? Why me? What the future held as a result of having a limb, What if?), and specific emotions (missing the limb, wish that they did not have an artificial limb, that they had their limb(s) back or that the accident had not happened and concern about getting employment).

In the same study, 46% considered that something good had happened as a result of the amputation. Participants stated many reasons as good things that happened following amputation such as: the Independence given to them by the amputation and the prosthesis, subsequent change in their attitude of life, improved coping abilities, financial benefits, elimination of pain and that amputation was a character building for some of them. Furthermore, finding positive meaning was significantly associated with more favorable physical capabilities and health ratings, lower levels of Athletic Activity Restriction and higher levels of Adjustment to Limitation[9].

Coping Styles[edit | edit source]

When there is time to think about impending loss, classic stages of grief may be experienced[4][10]:

- Denial; often manifest as refusal to engage in discussion or to ask basic questions about the planned procedure

- Anger: which may be directed towards the medical team, with expressions of being cheated or tricked into agreeing to an amputation

- Bargaining: by attempting to forestall the surgery or to delay it indefinitely for a myriad of reasons such as ‘’I’m too tired I don’t want to go through with any major surgery’’

- Depression: taking the form of learned helplessness’’ feeling of passivity, and being overwhelmed

- Acceptance: which may not be reached until the patient is into the rehabilitation process.

A minority of amputees experience denial in relation to accepting their impairment (i.e. the reality that their limb is missing). However, phantom sensation may play a role in reinforcing the denial. This degree of denial may lead to serious problems. Such a disconnection with reality may indicate some underlying psychosis and if this state persists for more than a few days and the amputee is not responding to counseling, a psychiatric assessment should be requested[1].

Maladaptive coping styles can be classified as overcompensation, surrender, or avoidance. 44 Overcompensation can take the form of hostility, excessive self-assertion (e.g., by refusing help that is needed), recognition seeking, manipulation, or obsessiveness (e.g., by becoming preoccupied with smaller details of care at the expense of regaining whatever enjoyment of life is still possible). Surrender may take the form of clinging to the sick role and continuing to demand a high level of nursing care, while refusing to undergo rehabilitation. Avoidance may result in psychological withdrawal, addictive self-soothing, or social withdrawal[4].

Mutilation anxiety is closely related to one's coping style and to the experience of pain. Prior to amputation, as part of the course of prevention (of both chronic vascular disease, as well as accidental injury), mutilation anxiety can be used to motivate patients for self-care and medical compliance. After amputation, mutilation anxiety may be a factor in referring a patient for psychotherapy or treatment of anxiety with medications. Mutilation anxiety may also affect the sexual function of a patient[11]. Men have reported feeling castrated by amputation, while women are more likely to report feeling sexual guilt and “punished” for some real or imagined transgression by amputation[12]. Medical management of fatigue, pain, and cosmesis of the stump can further alleviate these difficulties during the rehabilitation process[4].

In contrast, some amputees adapt effective coping styles that result from self-efficacy, using humor, making plans and visualizing the future, and actively seeking help to solve problems. The Way of Coping Check-List can be used to screen for patients at high risk for adjusting poorly to amputation and for having further negative sequelae.

Sub Heading 3

[edit | edit source]

Add text here...

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Therapy for Amputees: Third Edition by Barbara Engstrom MCSP DipMgt & Catherine Van de Ven MCSP

- ↑ Thompson D M, Haran D 1983 Living with an amputation: the patient. International Rehabilitation Medicine 5:165–169

- ↑ Srivastava, K., Saldanha, D., Chaudhury, S., Ryali, V., Goyal, S., Bhattacharyya, D. and Basannar, D. (2010). A Study of Psychological Correlates after Amputation. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 66(4), pp.367-373.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bhuvaneswar, C. G., Epstein, L. A., & Stern, T. A. (2007). Rounds in the General Hospital: Reactions to Amputation: Recognition and Treatment, 9(4), 303–308.

- ↑ NOBLE, D., PRICE, D. and GILDER, R. (1954). PSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES FOLLOWING AMPUTATION. American Journal of Psychiatry, 110(8), pp.609-613.

- ↑ Fukunishi I, Sasaki K, Chishima Y, Anze M, Saijo M General hospital psychiatry, vol. 18, issue 2 (1996) pp. 121-7

- ↑ Cavanagh, S., Shin, L., Karamouz, N. and Rauch, S. (2006). Psychiatric and Emotional Sequelae of Surgical Amputation. Psychosomatics, 47(6), pp.459-464.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Henker III, F. (1979). Body-image conffict following trauma and surgery. Psychosomatics, 20(12), pp.812-820.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gallagher, P., & Maclachlan, M. (2000). Prosthetics and Orthotics International. https://doi.org/10.1080/03093640008726548

- ↑ PARKES, C. (1975). Psycho-social Transitions: Comparison between Reactions to Loss of a Limb and Loss of a Spouse. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 127(3), pp.204-210.

- ↑ Shell, J. and Miller, M. (1999). The Cancer Amputee and Sexuality. Orthopaedic Nursing, 18(5), pp.53???64.

- ↑ Hogan, R. (1985). Human sexuality. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton-Century-Crofts.