Pregnancy Related Pelvic Pain

Original Editors - Marlies Verbruggen

Top Contributors - Marlies Verbruggen, Nicole Hills, Rotimi Alao, Andeela Hafeez, Lara Lagrange, Vanwymeersch Celine, Admin, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, WikiSysop, Evan Thomas, Fasuba Ayobami and Wanda van Niekerk

[See also Chronic Pelvic Pain]

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

According to the European guidelines of Vleeming et al [1], pelvic girdle pain can be defined as the following:

“Pelvic girdle pain generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ). The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis.”

According to literature, the prevalence of women who suffer from pelvic girdle pain during their pregnancy is about 20 %. [1] [2] [3] [4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The pelvis is composed of the sacrum, ilium, ischium and pubis. The pelvic bone consists of two joints: the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint.

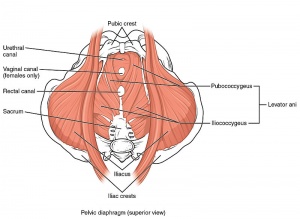

Pelvic Floor Anatomy

The Pelvic Floor is an area of muscles and connective tissue and has several functions:

• Separating the pelvic cavity above from the perineal region below.

• It provides support to the pelvic viscera (the bladder, intestines and uterus).

• It assists with continence through control of the urinary and anal sphincters.

• It facilitates birth by resisting the descent of the presenting part.

• It helps to maintain optimal intra-abdominal pressure. [20]

Sacroiliac Joint

The sacroiliac joint is the connection between the spine and the pelvis . The main functions of the SI joint are: provide stability and compensate the load of the trunk to the lower limbs. The ligaments stabilizing the SI joint are the strongest ligaments in the body: [21] [22]

• Lig. Anterior Sacroiliac

• Lig. Interosseus Sacroiliac

• Lig. Posterior (Dorsal) Sacroiliac

• Lig. Sacrotuberous

• Lig. Sacrospinous

There are a lot of muscles who are attached to the sacrum to provide stability in the joint. These muscles are classified according to their primary function in the hip joint:

• Adduction: Adductor brevis/ longus /Magnus, Gracilis, Pectineus, Latissimus dorsi

• Abduction: Gluteus maxiumus/ medius/minimus, Tensor fascia lata,

• External rotation: Obturator internus /externus, Quadratus femoris/lumborum, Piriformis, Superior gemellus, Inferior gemellus, Pectineus, Adductor brevis/magnus, Gluteus maxiumus/ medius, Sartorius, Psoas minor

• Internal rotation: Tensor fascia lata, Gluteus medius/minimus, Semitendonosus,

• Retroflexion: Biceps femoris, Latissimus dorsi, Gluteus maxiumus/ medius, Semimembranosus, Semitendonosus, Adductor magnus

• Anteflexion: Iliacus, Sartorius, Tensor fascia lata, Rectus femoris, Psoas minor

• Anteflexion trunk: External oblique, Internal oblique

• Lateral flexion trunk: External oblique, Internal oblique, Multifidus

• Contralateral rotation trunk: External oblique

• Supporting the pelvic floor: Levator ani

• Abduction and flexion coccyx : Coccygeus

• Control of urination: Sphincter urethrae

• Bending flexion of the anus and tension of the vagina during an orgasm: Superficial transverse perineal ischiocavernous

• Compression abdomen: Transversus abdominus, Rectus abdominis, Pyramidalis, Internal oblique

Force and Form Closure

• Form closure:

The sacrum and the ilium fit into each other and ensure thus stability.

• Force closure:

This term is used to describe the other forces acting across the joint to create stability. Muscles, ligaments and the thoracolumbar fascia all contribute to force closure. It creates greater friction and therefore an increased stability. [22]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The exact underlying mechanisms, leading to the development of pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy, are uncertain or speculative. [1] [2] [5] [3] Literature actually proposed different, etiologic hypotheses like biomechanical, genetic, traumatic, hormonal, metabolic and degenerative factors. [1][2][18]

The combination of hormonal and biomechanical factors seems to be the most trustworthy hypothesis that can explain the development of pregnancy–related pelvic girdle pain. During pregnancy the female body is exposed to certain factors that have an impact on the dynamic stability of the pelvis. The optimal stabilization of the pelvis is absolutely essential because the pelvis serves as a platform that must transfer the load from the trunk to the legs. Vleeming et al. published in 2008 a definition of optimal stability: “The effective accommodation of the joints to each specific load demand through an adequately tailored joint compression, as a function of gravity, coordinated muscle and ligament forces, to produce effective joint reaction forces under changing conditions”. Optimal stability depends on an efficient force closure, form closure, motor control and is influenced by our emotions. The central nerve system (CNS) chooses a dynamic (for example, inertia of limb segments and force-velocity relationships of muscles) or static (the force-length relationship of muscles and their moment arm-angle relationships or torque-angle relationships) movement strategy, depending on emotions (i.e. fear, anxiety) and perceptions, which results in specific muscle forces and in coordinated muscle activity. For example: when someone is feeling depressed, there will be a smaller concentration of the neurotransmitter serotonin available in the body of this person. Serotonin has an important role in our body posture, if there is a deficit of this neurotransmitter muscles will not work properly, which causes instability. [18] [19] [23]

So first of all the stabilization is from major concern because it determines if the load will be effectively transmitted. Secondly an optimal stabilization of the pelvis guarantees that the shear forces will be minimized across the joints.

The stabilization, which is acquired by three specific anatomic characteristics, is mainly needed at the sacroiliac joints. In the articular surfaces of the sacroiliac joints there are ridges and grooves that form the first part of stabilization. Secondly the sacrum has a wedge shape, which allows it to fit tightly between the ilia. Finally there are additional compression forces which are generated by the muscles, fascia and ligaments, that attach to the pelvis and act across the sacro-iliac joints to give the joints their stability. Women produce increased quantities of a polypeptide hormone, namely relaxin, during their pregnancy. The effect of the levels of progesterone to the pelvic girdle ligaments is also established. Consequently there is greater ligamental laxity, especially in the joints of the pelvis by relaxing the connective tissue. In a systematic review, Mens et al.[6] recently established that patients who suffer from pelvic girdle pain have increased motion in their pelvic joints compared with healthy pregnant controls. If this is not compensated by altered neuromotor control, pain may result. The exact role of each specific hormone and the reasons for its variations in serum levels is not known, but the primary aim is to maintain pregnancy and to initiate delivery. [18]

The increased motion of the pelvic joints results in negative consequences, namely that the efficiency of load transmission will be diminished. Furthermore the increase of motion will increase the shear forces across the joints. It’s possible that these increased shear forces are responsible for the pain in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain. [1] [5]

There is also a significant reduced strength of the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, pelvic floor, lumbar multifidus and an inadequate coordination of the lumbopelvic muscles is often observed by pregnant women with PGP. When PGP arises in the 2nd and 3th trimester of pregnancy, abdominal stretching and a shift of body gravity center can possibly cause this muscle impairment. The reduced force closure can lead to neuromuscular compensatory strategies. There are two common compensating strategies, namely the butt-gripping and the chest-gripping strategy. In the butt-gripping strategy there is an overuse of the posterior gluteal muscles. In the chest-gripping strategy the external oblique is in overdrive, which means that the external oblique is going to work/contract harder and faster to compensate the underuse of the transversus abdominis. This leads to an incorrect load transfer between the throax and the pelvis, which can cause hypertrophy of the external oblique. These strategies, the butt-gripping and chest-gripping strategies, may increase sheared forces in the SIJ, which might cause pain. In response to the pain there are two maladaptive forms of behavior: pain avoidance and pain provocation behavior, this can increase pain and disability. [18] [24]

The increased motion of the pelvic joints results in negative consequences, namely that the efficiency of load transmission will be diminished. Furthermore the increase of motion will increase the shear forces across the joints. It’s possible that these increased shear forces are responsible for the pain in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain. [1] [5]

We can divide the patients who suffer from pelvic girdle pain into five subgroups depending on symptoms and the localization of pain. [1] [7] [2] [5] [8] [18]

- Pelvic girdle syndrome : including symptoms of anterior and posterior pelvic girdle, symphysis pubis and bilateral joints

- Symphysiolysis : including symptoms of the anterior pelvic girdle and pubic symphysis

- One sided Sacroiliac syndrome : including symptoms of the posterior pelvic girdle and unilateral sacroiliac joint.

- Double-sided Sacroiliac syndrome : including symptoms of the posterior pelvic girdle and bilateral sacroiliac joints

- Miscellaneous : including inconsistent findings of the pelvic girdle.

The risk factors for the development of pregnancy–related pelvic girdle pain are :

- A previous history of low back pain [1] [2] [5] [3] [6]

- Previous trauma to the pelvis or back [1] [2] [6]

- Previous history of pelvic girdle pain [2] [5] [3]

- High-work load or strenuous work (twisting and bending the back several times per hour) [1] [2] [5] [3]

- Parity-related factors [1][18]

There are a few factors that had a weak evidence who influence the risk for development of pregnancy–related pelvic girdle pain: [18] [9]

- Early menarche

- IUDs (Intrauterine devices)

- Increased weight during pregnancy

There are also a few factors that had a conflicting evidence who influence the risk for development of pregnancy–related pelvic girdle pain like :

- The use of contraceptive pills [1] [2] [5] [6]

- Time interval since last pregnancy [1] [2] [5] [6]

- Height [1] [5]

- Weight [1] [5]

- Smoking [1] [2] [5]

- Age [1] [2] [5] [6]

- Epidural / spinal anesthetic [2] [5]

- Analgesic techniques [5]

- Bone density [2] [3]

- Foetal weight [2]

- Number of previous pregnancies [2]

- Maternal ethnicity [2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The clinical presentation of pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain is characterized by a wide variation of symptoms.

Pain

Timeline: Often, the onset of pain occurs around the 18th week and reaches peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy. The pain can spontaneously disappear within 3 months, but 7-8% of the patients have a persisting, chronic pain. [3] [18]

Localisation: Pain is often localized deep in the sacral/gluteal region. [1] [3] The localization of pain is deep and can be divided in five groups as mentioned above under ‘etiology and epidemiology’. It’s even possible that localization of the pain changes over time.

Nature of pain: Pelvic girdle pain has been described as “stabbing’’ , pain in the lower back as a “dull ache’’ and the pain in the thoracic spine is rather “burning’’. Other pain-descriptions are: shooting pain, feeling of oppression and a sharp twinge. [18]

Intensity of pain: The intensity of pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS) is usually around 50-60 mm. [2] [3] %The pain may be mild or quite bearable in about half of the cases and very serious in about 25%. [1][3][18]

Changes in the perception and execution of movements

Changes in the perception of movement: Several women reported a “catching” sensation in their upper leg when they were walking. Patients with PPP also experienced a feeling of paralysis in their legs while they were lifting their leg in extension. [3]

Changes in movement coordination: Women with postpartum PGP have a stronger coupling between pelvic and thoracic rotations during gait. This may be a strategy chosen by the nervous system to cope with motor problems. [3]

Patients, who suffer from pelvic girdle pain, have difficulty during:

- Walking (quickly): alternated gait pattern (slower walking velocity, waddling type of gait) [1] [2] [3]

- Sexual intercourse [2] [3]

- During sleep : Turning in bed [3] [4]

- Housework [3] [4]

- Activities with children [3] [8]

- Sitting [4]

- Standing for 30 minutes or longer [4]

- Climbing stairs [4]

- Running (postnatal) [4]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of pelvic pain in women can be challenging because many symptoms and signs are insensitive and nonspecific. As the first priority, urgent life-threatening conditions (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, ruptured ovarian cyst, ovarian vein thrombosis, placental abruption) , fertility-threatening conditions (e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, endometritis), painful visceral pathologies of the pelvis (urogenital and gastrointestinal), lower-back pain syndromes (e.g. lumbar disc-lesion, rheumatism or sciatica) , bone or soft tissue infections, urinary tract infections, femoral vein thrombosis, rupture of symphysis pubis and bone or soft tissue tumors must be considered. [2]

The most common urgent causes of pelvic pain are pelvic inflammatory disease, ruptured ovarian cyst, and appendicitis; however, many other diagnoses in the differential may mimic these conditions, and imaging is often needed. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be the initial imaging test because of its sensitivities across most etiologies and its lack of radiation exposure. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for pelvic inflammatory disease when other etiologies are ruled out, because the presentation is variable and the prevalence is high. Multiple studies have shown that 20 to 50 percent of women presenting with pelvic pain have pelvic inflammatory disease. Adolescents, pregnant and postpartum women require unique considerations.[12]

A careful medical history focusing on pain characteristics is necessary, the patient should be asked about the location, intensity, radiation, timing, duration, and exacerbating and mitigating factors of the pain. Review of systems, gynecologic, sexual, and social history, in addition to physical examination and an appropriate laboratory test, helps to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Urinalysis, midstream specimen of urine (MSU).

- High vaginal swab (HVS) for bacteria and endocervical swab.[1]

- Pregnancy test.

- FBC/A full blood count: this is a very common blood test and is used to check a person's general health as well as screening for specific conditions. The number of red cells, white cells and platelets in the blood are checked. [25]

- Urgent ultrasound (if miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy is suspected).

- Laparoscopy[7]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)

Examination[edit | edit source]

The following tests are recommended for the clinical examination, to make the diagnosis of pelvic girdle pain:

For SIJ pain :

- Posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4) [1][2][8] [9][10][11]

- Patrick ‘s Faber test [1][2] [10]

- Palpation of the long dorsal SIJ ligament [1][2][8][10][11]

- Gaenslen’s test [1][2][9][10]

- See also SIJ Special Test Cluster

Symphysis :

- Palpation of symphysis[1][2][8][10]

- Modified trendelenburg’s test of the pelvic girdle [1][2][8][10]

Functional pelvic test :

- Active straight leg raise test (ASLR test) [1][2][8][11]

It’s also very important to ask the patient about his pain history. The use of a pain location diagram is strongly recommended, so that we can be sure that the pain is localized in the pelvic area. The patient may also point out the pain location on his or her body. [1]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

a) Physical therapy for pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy (Evidence level C)

According to the European guidelines of Vleeming et al., exercises are recommended during pregnancy. These exercises should focus on adequate advice concerning activities of daily living and to avoid maladaptive movement patterns. [1] (Evidence: C) There are not a lot of studies who examined the effects of exercises on pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. These interventions are different with regard to duration and type of the exercises as well as performing individually or in groups. There should be more research for new therapies in the future. [1] [12]

b) Physical therapy for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy (Evidence level C)

A very important aspect of the therapy for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy is the focus on specific stabilizing exercises. It has been proven that this type of exercises have a positive effect on pain, functional status and health-related quality of life. [1][13][8][14]

The treatment program actually includes several important factors like [8] :

- Informing the patient about body awareness as well as ergonomic advice in real life situations. These situations can be really specific like carrying or lifting a child.

- Joint mobilization, massage, relaxation and stretching can be executed when indicated.

- However the accent has to remain on exercise and training.

The program, for exercise and training, consists of [8]:

- Specific training of the abdominal muscles, which are transversely oriented. This must be performed with co-activation of the lumbar multifidus at the lumbosacral region.

- The following muscles will be trained : M. gluteus maximus, M. latissimus dorsi, M. oblique abdominal muscles, M. erector spinae, M. quadrates lumborum end the hip adductors and abductors.

In the initial stage, the treatment program focuses on the training of specific contractions of the deep muscle system, independently from the superficial muscle. The deep muscle system consists of m. transversus abdominis (TrA), obliquus internus, multifidus, pelvic floor and the diaphragm. During all exercises and daily activities they emphasize the importance of activating these muscles before adding the superficial muscles. Depending on clinical findings this focus was combined with information, ergonomic advice, body awareness training, relaxation of global muscles and mobilization. [8][14]

Exercises for the superficial muscles were gradually added to the program, when low force contractions of the transversely oriented abdominal muscles were achieved. [14]

Summary of the exercises [8]

File:Clip image002.gif

Legend: CG = Control Group, SSEG = Specific Stabilizing Exercise Group.

The Therapy Master, which is an exercise device, can be utilized to facilitate the exercise progression for most of the exercises. [8][14]

In literature [8] the patients performed these exercises 30 to 60 minutes, 3 days a week, and this for 18 to 20 weeks. They also started with three series of ten repetitions of each exercise. [8]

The quality of the execution of the exercise determined the number of exercises and number of repetitions. Each patient received specific stabilizing exercises out of a fixed menu (see photo). The patients may have muscle soreness, but the exercises may not provoke pain at any time. It’s also very important that the patient maintains lumbopelvic control during the performance of these exercises. [8][14]

Patients often have a flare-up of pain when exercising, but this is likely from progressing the exercise load too quickly. This study[8] used an exercise diary so the patient could describe her progression, and seemed to be effective in avoiding flare-ups. [8]

It’s well documented that exercise supervision is critical for improving quality of exercise performance. [8][14]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

[Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1TkPOxkdaxtpnrlazfSVvEYv7UEU-hEcI5FQZdo-kB-Bksi9kl!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Jun 2008; 17(6) : 794-819.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: un update. BMC Medicine Feb 2011; 9: 1-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JMA, Van Dieën JH, Wuisman PIJM, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I : Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal Nov 2004; 13(7) : 575-589.

- ↑ Nielsen LL. Clinical findings, pain descriptions and physical complaints reported by women with post-natal pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica 2010: 89; 1187-1191.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedVERM - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Albert HB, Godskesen M, Korsholm L, Westergaard JG. Risk factors in developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica 2006; 85 : 539-544.

- ↑ http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/pelvic-pain#ref-1

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vollestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Spine Feb 2004 : 29(4) ; 351-359.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGUTK - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedOLSE - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Vollestad NK, Stuge B. Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Feb 2009: 18; 718-726.

- ↑ Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N. Physical therapy for pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2003: 82; 983-990.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSTUG - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Stuge B,Holm I, Vollestad N. To treat or not to treat postpartum pelvic girdle pain with stabilizing exercises? Manual therapy 2006: 11; 337-343.