Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Donald John Auson, Astrid Lahousse, Stefanie Van De Vijver, Roxane Roosens, Kim Jackson, Pauline Bouten, George Prudden, Laure Lievens, Manisha Shrestha, Rosie Swift, Mariam Hashem, Lucinda hampton, Sai Kripa, Shreya Pavaskar and Ahmed M Diab

Search Strategy

[edit | edit source]

Databases Searched: Pubmed, Web of Knowledge, PEDro, Web of Science

Keywords: Low back pain, Spinal Stenosis, LSS, lumbar spinal stenosis, degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a degenerative condition in which there is diminished space available for the neural and vascular elements in the lumbar spine secondary to degenerative changes in the spinal canal.[41] This compression can also cause radiating pain and numbness to the buttock, thigh, or leg particularly during walking or standing for a long time. The pain reduces usually when a patient is in resting, sits down or bends forward. Spinal stenosis is related to aging, affecting mostly individuals over the age of 60 years. [12] Not all patients with spinal narrowing develop symptoms, so the term "spinal stenosis" refers to the symptoms of pain and not to the narrowing itself. [5]

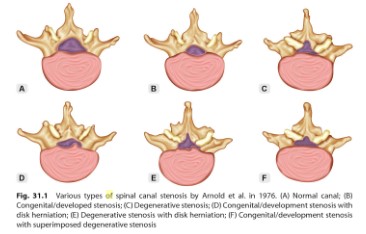

There are various types of spinal canal stenosis (Fig 1).

Fig. 1: Various types of spinal canal stenosis [51]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spinal stenosis refers to an anatomic and pathologic condition that includes the narrowing of the lower spinal canal (central stenosis) or one or more lumbar vertebral foramina (foraminal/lateral stenosis).

There are 33 spinal cord nerve segments in a human spinal cord, and 5 lumbar segments that form 5 pairs of lumbar nerves. [8]

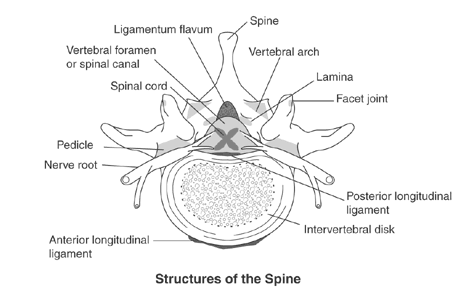

Following structures of the spine are most involved in lumbar spinal stenosis:

- Disci intervertebrales (intervertebral discs): There is one disc between each pair of vertebrae, except for the first cervical segment, the atlas. The center is called the nucleus pulposus. This nucleus is surrounded by the annulus fibrosus, which contains several layers of fibrocartilage. the intervertebral disc acts as shock absorbers.

- Facet joints: Synovial joints located on the back of the main part of the vertebra. They are formed by the superior articular process of the underlying vertebra and the inferior articular process of the vertebra lying above it. They connect the vertebrae to each other and permit backward motion. Facet joints

- Foramen intervertebrale (intervertebral foramen): An opening between vertebrae through which nerves leave the spine and extend to other parts of the body.

- Ligaments: Fibrous bands of connective tissue that connect two or more bones together and help stabilize joints They support the spine by preventing the vertebrae from slipping out of line as the spine moves. A large ligament often involved in spinal stenosis is the ligamentum flavum, which runs as a continuous band from lamina to lamina in the spine.

- Medulla spinalis (Spinal cord/nerve roots): Throughout the entire spine there is a central spinal canal which contains the spinal cord. It is a long, thin, tubular bundle of nervous tissue which is surrounded by the vertebrae. The spinal cord is part of the central nervous system providing a means of communication between the brain and the rest of the body.

- Cauda equina: A sack of nerve roots that continues from the lumbar region, where the spinal cord ends, and continues down to provide neurologic function to the lower part of the body. [4]

Fig. 2: Anatomy of the spine [6]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of relative and absolute LSS increased respectively from 16.0% to 38.8% and from 4.0% to 14.3% between age <40 years and 60+ years. If we take a closer look at the 60-69 year-old group, the prevalence of acquired stenosis increases with age to relative 47.2% and absolute 19.4%. [32], [49]

It is an extensive problem in the elderly, presenting with pain, disability, fall risk and depression. [44] (level of evidence 2A)

Some people are born with a small spinal canal. This is called "congenital stenosis”. However, spinal canal narrowing is most often due to age-related changes that take place over time. This condition is called "acquired spinal stenosis." Spinal stenosis is most common in people over 50 years of age. [14]

Acquired forms of LSS are further classified as degenerative, spondylolisthetic, iatrogenic (postsurgical), posttraumatic, or combined. [14]

Lumbar spinal stenosis can be caused by:

- osteoarthritis

- inflammatory spondyloarthritis

- bulging of the disc

- thickening of the vertebral ligament

- tumor

- infection

- various metabolic bone disorders that cause bone growth, such as Paget's disease [1,12,14]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The symptom most commonly attributed to LSS is neurogenic claudication, also referred to as pseudo-claudication. [42]

Symptoms of spinal stenosis often start slowly and get worse over time. Pain in the legs may become so severe that walking, even short distances, is unbearable. Frequently, patients must sit or lean forward to temporarily ease pain. [1,12,15]

Neurogenic claudication refers to leg symptoms encompassing the buttock, groin and anterior thigh, as well as radiation down the posterior part of the leg to the feet. In addition to pain, leg symptoms can include fatigue, heaviness, weakness and/or paraesthesia. Patients with LSS also can report nocturnal leg cramps and neurogenic bladder symptoms. Symptoms can be unilateral or more commonly bilateral and symmetrical. A key feature of neurogenic claudication is its relationship to the patient’s posture where lumbar extension increases and flexion decreases pain. Symptoms progressively worsen when standing or walking and are relieved by sitting.

Relief with sitting in LSS contrasts with most nonspecific low back pain, which is commonly exacerbated by prolonged sitting. Patients with neurogenic claudication report that laying flat is often associated with less relief while lying on the side (permitting lumbar flexion) is more comfortable.[42]

Some patients may report symptoms that are difficult to definitively attribute to LSS. For example, they may only report low back pain (without leg symptoms), which are typical of neurogenic claudication (e.g., characteristic positional nature of symptoms).[42]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Pathologies/diseases that mimic lumbar spinal stenosis are:

- disc herniation

- spinal cord primary or secondary tumor

- peripheral neuropathy

- osteoarthritis of hips or knees

- osteoporotic/lumbar compression fracture

- myofascial pain

- rheumatoid arthritis

- lumbar degenerative disk disease

- lumbar facet arthropathy

- lumbar spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis and spondylodiscitis

- mechanical low back pain

- cauda equina syndrome = red flag

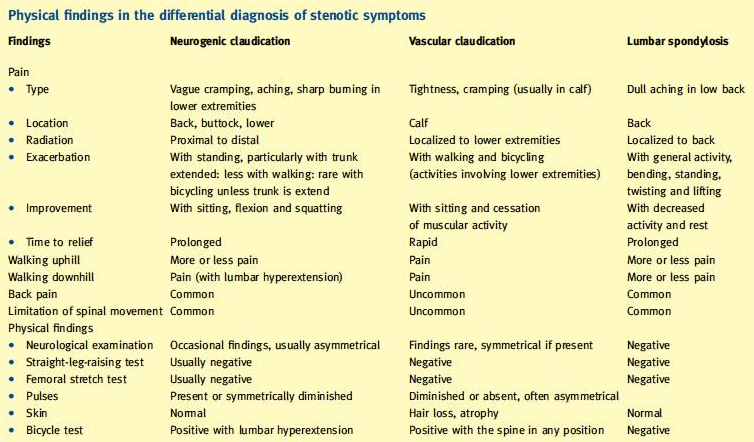

A difference must be made between neurogenic claudication caused by LSS, lumbar spondylosis, or vascular claudication. You can find all the differences between Lumbar spondylosis, neurogenic and vascular claudication in table 1.

Table 1: Physical finding in the differential diagnosis of stenotic symptoms [42]

Older patients (>60-65 years) with back or leg pain, diagnostic possibilities differ from younger patients: non-mechanical causes of back pain, such as malignancy, infection or abdominal aortic aneurysm are common in elderly patients. [8]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

First the clinical diagnosis of LSS, and exclusion of other competing diagnoses: the history and medical history of the patient should be questioned. Ask for a description of symptoms and for any injury, condition, or general health problem that might be causing the symptoms.

The therapist checks for pain or symptoms when the patient hyper-extends the spine (bends backwards), and checks for normal neurologic function (for instance, sensation, muscle strength, and reflexes) in the arms and legs.

Furthermore, a variety of measurements can be used to assess treatment of patients with LSS. The underlying cause of LSS is identified by imaging techniques such as [32] (level of evidence 1A):

- Radiography is usually the first step to identify a degenerative process (disc degeneration, osteophytes, facet hypertrophy).

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) (T2 weighted) is used for determining the degree of stenosis and the thickness of Ligamentum Flavum.

o Diameter of 10 mm of the spinal canal equals absolute stenosis;

o Diameter of 12 mm indicates severe stenosis.

- By means of a CT scan a cross-section of the spinal canal may reveal the effects of disk pathology, facet hypertrophy and buckled Ligamentum Flavum. Nonetheless a CT scan has poor soft-tissue contrast, which is why a myelography is usually conducted simultaneously.

- Triple sequence [44] (level of evidence 2A)

- Ultrasound (US) [44] (level of evidence 2A)

- Myelography [44] (level of evidence 2A)

To date, we are unaware of an identified association between patient report of symptoms, functional outcomes (Oswestry), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and anatomical impairment in patients with LSS . [44] (level of evidence 2A)

The severity of the structural pathology has a poor correlate with the severity of symptoms and limitation. [14]

In fact, examination of asymptomatic subjects showed that >30% had canal narrowing that would be classified as consistent with LSS. Imaging therefore cannot be considered a gold-standard in diagnosis of LSS, and must only be considered as an adjunct to a thorough physical examination. [44] (level of evidence 2A)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- The Modified Oswestry Disability Index (MOSW). [13, 17, 50]

- The Satisfaction Subscale of the Spinal Stenosis Scale (SSS); this is a test for psychological well-being.

- A numerical Pain Rating Scale (NRPS) for average thigh/leg pain [10]

- The Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire [13]

- The Oxford Spinal Stenosis Score [13]

- Visual analogue scale [50,17]

- Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire [50]

- A self-administered, self-reported history questionnaire (SSHQ) [43]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination for patients with LSS is usually normal or demonstrates nonspecific findings. Patients with stenosis often have lumbar, paraspinal, or gluteal tenderness, which is usually related to underlying degenerative changes, muscle spasms, and poor posture.

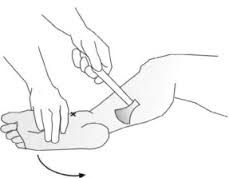

The neurologic examination is usually normal or reveals only subtle abnormalities such as mild weakness, sensory changes, and reflex abnormalities. The achilles tendon reflexes (Fig. 4) are often diminished, while abnormal knee reflexes are less common. The straight leg-raise test and other neural tension signs are usually negative unless there is accompanying disc herniation. Hamstring tightness is often present and may produce a false-positive straight leg-raise test. [9] (level of evidence 3B) ,[12](level of evidence 3B)

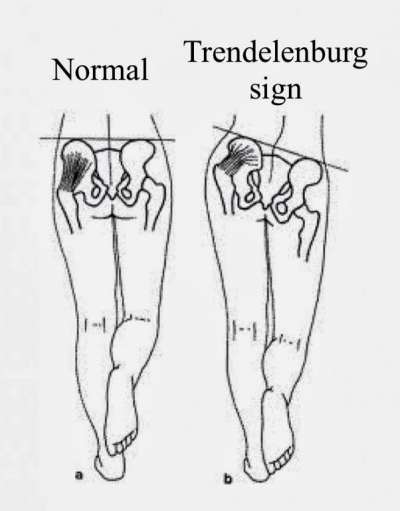

A careful motor examination should be performed. Leg weakness is generally mild and in the distribution of the L4, L5, or S1 nerve roots. Weakness of the muscles innervated by L5 is the most common finding. If the physiotherapist wants to demonstrate the spinal level truly responsible for the symptoms of LSS, it is recommended to use the gait-loading test which is a provocation test (level of evidence 3B). The lumbar extension-loading test (Fig. 5) is useful for assessment of lumbar spinal stenosis pathology and is capable of accurately determining the involved spinal level. In this test, you have to maintain the lumbar region in moderate (angle of 10°-30°)extension while standing as long as you can. After the patient has performed this test, changes in subjective symptoms and objective neurological findings can be evaluated [33](level of evidence 3B). The examiner should test for weakness of great toe extensors and hip abductors as well. The Trendelenburg test (Fig. 6) is used to observe for hip abductor weakness. Difficulty with walking on the toes suggests S1 root involvement. Difficulty with heel walking suggests L4 or L5 nerve dysfunction. [12] (level of evidence 3B)

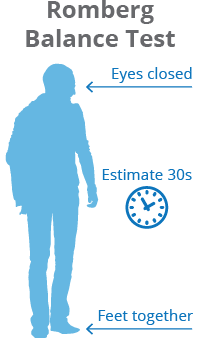

Katz et al report physical examination findings most strongly associated with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) include wide-based gait, abnormal Romberg test, (Fig. 7) thigh pain following 30 seconds of lumbar extension, and neuromuscular abnormalities [46] ; however, Fritz et al state physical examination findings do not seem helpful in determining the presence or absence of LSS. [47]

The classic presentation of LSS is radiating leg pain associated with walking that is relieved by rest (neurogenic claudication). When patients bend forward, the pain diminishes.

Physical examination findings are frequently normal in patients with LSS. Nevertheless, review of the literature suggests diminished lumbar extension appears most consistently, varies less, and constitutes the most significant finding in LSS. Other positive findings include loss of lumbar lordosis and forward-flexed gait. [7]

Fig. 4: Achilles tendon reflexes [2]

Fig. 5: Lumbar extension loading test [3]

Fig. 6: Trendelenbrug sign [3] Fig. 7: Romberg balance test [3]

Bewaren

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Surgery

If non-operative treatment has failed, surgical treatment may be considered. The key in deciding whether or not to have surgery is the degree of physical disability and disabling pain. In most cases of advanced claudication (spinal or vascular), a decompression surgery is required to alleviate the symptoms of spinal stenosis. [18]

Decompressive posterior laminectomy is the most common type of surgery to treat spinal stenosis. The goal of this surgery is to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or spinal nerve roots. If instability is present, autogenous intertransverse bone grafting is recommended. In some cases, spinal fusion (arthrodesis) may be done at the same time to help stabilize sections of the spine treated with decompressive laminectomy.[19,20] The most common surgical complication is dural tear. [8]

Steroid injections

Nerve roots may become irritated and swollen at the area where they are pinched. Injecting a corticosteroid into the space around the compression can help reduce the inflammation and relieve some of the pressure. It is suggested that epidural steroid injections help to control severe radicular symptoms in patients with spinal stenosis. However, repeated steroid injections can weaken nearby bones and connective tissue.[12]

Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Medications

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are commonly prescribed for patients with LSS, and often help relieve pain associated with spinal stenosis. By reducing inflammation, these medications can relieve some of the pressure on compressed nerves. [21]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

LSS patients frequently receive early surgical treatment, although conservative treatment can be a viable option. Not only because of the complications that can arise from surgery, but also because mild symptoms of radicular pain often can be lightened with physical therapy. [39] (Lumbar Radiculopathy) However, in patients with severe LSS, surgery overall seems to be a better option than conservative interventions such as injections and rehabilitation. Still, its specific content and effectiveness relative to other nonsurgical strategies has not been clarified yet. [38] Postoperative care after spinal surgery is variable, with major differences reported between surgeons in the type and intensity of rehabilitation provided and in restrictions imposed and advice offered to participants. Postoperative management may include education, rehabilitation, exercise, behavioral graded training, neuromuscular training and stabilization training. [40]

Numerous physical therapy interventions have been recommended for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, suggesting a role for general conditioning using body weight–supported treadmill walking or stationary cycling, strengthening exercises for the trunk and lower extremities, and manual therapy for the spine and hips. [38]

There is low quality evidence that treadmill walking exercise with body-weight support (corset) is as effective as cycling at short notice. Low quality evidence suggests an improvement in walking ability wearing a lumbar corset in comparison with an elastic woolen corset or no corset. [37] It can be worn during daily activities that require walking, but only worn for only a limited number of hours each day, otherwise the paraspinal muscles can atrophy [32]. Furthermore, low quality evidence indicates that modalities such as ultrasound, TENS, heat packs and manual therapy in addition to an exercise program, do not upgrade the active exercises. [37]

In general, two recent level 1A reviews on literature [38][37] concluded that there was no consistent evidence for the effectiveness of physical exercise therapy. The specific elements of physical therapy that may benefit should further be examined, as well as the optimal dosage.

Nevertheless, exercise that promotes physical fitness, can improve pain and overall well- being and controls overweight. It is known that obesity affects chronic back pain, including pain related to spinal stenosis, due to mechanical forces (weight load) in addition to chronic circulating inflammatory chemicals from active adipose tissue. Additionally, obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 30) is an independent risk factor for lower back pain. [32] Cycling and other exercises performed during flexion of the spine, are usually better tolerated than walking. [15]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Julie M Fritz, et al., A Nonsurgical Treatment Approach for Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 1997

Resources

[edit | edit source]

[1] http://www.rheumatology.org/Practice/Clinical/Patients/Diseases_And_Conditions/Spinal_Stenosis/

[2] http://hjd.med.nyu.edu/spine/patient-education/spine-problems/back-and-leg-pain/lumbar-spinal-stenosis

[3] https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=uh1931

[4] David G. Borenstein, James S. Panagis, Peter C. Gerszten, and James N. Weinstein, Questions and answers about spinal stenosis, National institute of health http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Spinal_Stenosis/#spine_c (level of evidence: 5)

[5] Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire: http://www.scientificspine.com/spine-scores/swiss-spinal-stenosis-questionnaire.html

[6] http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457481.html

[23] http://www.apparelyzed.com/cauda-equina-syndrome.html [24] http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/spinal-stenosis/basics/causes/con-2003610)5

[29] Barley Lake, Spinal cord injuries, http://www.sci-recovery.org/sci.htm (level of evidence: 5)

[33] http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/259

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a condition where the spinal canal (central stenosis) or one or more of the lumbar vertebral foramina (foraminal/lateral stenosis) becomes narrowed. If the narrowing is substantial, it can cause compression of the spinal cord or spinal nerves. Symptoms of spinal stenosis include low back pain, buttock pain, leg pain and numbness. These symptoms are typically aggravated by walking and relieved by resting. Interventions that may help relieve symptoms of spinal stenosis and prevent progression of the condition include: education, strenghtening, stretching, mobilization, pelvic tilts and lower back stabilization. If non-operative treatment does not relieve symptoms, surgical treatment may be appropriate. Decompressive posterior laminectomy is the most common type of surgery.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Lee CH, et al., Decompression Only Versus Fusion Surgery for Lumbar Stenosis in Elderly Patients Over 75 Years Old: Which is Reasonable, 2013

Kang MH, et al., The effects of lumbo-pelvic postural taping on gait parameters in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, 2013

Andreisek G, et al., A systematic review of semiquantitative and qualitative radiologic criteria for the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis, 2013

Syrimpeis V, et al., Lumbar vertebral hemangioma mimicking lateral spinal canal stenosis: Case report and review of literature.

References[edit | edit source]

[7] Cohen et al., The anatomy of the cauda equina on CT scans and MRI, University of California, San Diego (level of evidence: 3B)

[8] James N. Weinstein, et al., Surgical versus Nonsurgical Therapy for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 2008, The new england journal of medicine (level of evidence: 2B)

[9] Jeffrey N. Katz, et al., Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Diagnostic Value of the History and Physical Examination, 1995, American College of Rheumatology (level of evidence: 3B)

[10] Whitman JM, Flynn TW, Childs JD et al. A Comparison Between Two Physical Therapy Treatment Programs for Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. SPINE. 2006; 31(22): 2541-49, Department of Physical Therapy, Regis University (level of evidence: 1B)

[11] Levent Ediz et al., Comparison of the efficacies of two different Physical Therapy Treatment Programs in Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 2011, Sakarya Medical Journal (level of evidence: 1B)

[12] Daniel J. Mazanec, et al., Lumbar canal stenosis: Start with nonsurgical therapy, 2013 (level of evidence: 3A)

[13] Pratt, The Reliability of the Shuttle Walking Test, the Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire, the Oxford Spinal Stenosis Score, and the Oswestry Disability Index in the Assessment of Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 2002 (level of evidence: 2B)

[14] Julie M Fritz, et al., A Nonsurgical Treatment Approach for Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 1997, Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association

(level of evidence: 3B)

[15] Katz JN and Harris MB. Clinical Practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008; 358(8): 818-825. (level of evidence: 2B)

[16] Naylor A. Factors in the development of the spinal stenosis syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg

Br 1979;61(3):306–9. (level of evidence: 5)

[17] SANNA SINIKALLIO, Lumbar spinal stenosis patients are satisfied with short-term results of surgery – younger age, symptom severity, disability and depression decrease satisfaction, 2007, Disability and Rehabilitation (level of evidence: 2B)

[18] Hilibrand et al., Degenerative lumbar stenosis: diagnosis and management, 1999, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (level of evidence: 2B)

[21] Weinstein et al., Surgical versus Nonsurgical Therapy for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 2008, The New England Journal of Medicine (level of evidence: 2B)

[22] Stephane Genevay, Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 2010, Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology

(level of evidence: 5)

[25] Atlas SJ, Delitto A. Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 443:198. (level of evidence: 5)

[26] McGregor AH, et al., Rehabilitation following surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis, Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2013. (level of evidence: 1A)

[27] Daniel J. Mazanec, et al., Lumbar canal stenosis: Start with nonsurgical therapy, 2013 (level of evidence: 3A)

[28] Cohen et al., The anatomy of the cauda equina on CT scans and MRI, University of California, San Diego (level of evidence: 3B)

[29] S. Genevay and S.J. Atlas, Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, Best Practice Research Clinical Rheumatology, 2010; 24(2):253-265 (level of evidence: 1B)

[30] J. N. Katz, et al., Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, The New Engeland Journal of Medicine, 2008; 358:818-25 (level of evidence: 3B)

[31] D. K. Binder et al., Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, Seminars in Neurology, 2002; Volume 22, number 2 (level of evidence: 3B)

[32] Costandi et al. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Therapeutic Options Review. Pain practice: World Institute of Pain. 2014 (level of evidence: 1A)

[34] Eui-Ryong Kim. Effects of a Home Exercise Program on the Self-report Disability Index and Gait Parameters in Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (level of evidence: 2B)

[35]. Krakow et al., Guidelines for the prenatal diagnosis of fetal skeletal dysplasias, Genet med. 2009; 11(2):127-133 (level of evidence: )

[36] L.Kalichman et al., Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: The Framingham Study, Spine Journal. 2009 July; 9(7): 545-550 (level of evidence: )

[37] Macedo, L. et al. Physical Therapy Interventions for Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy, 2014, 93(12), 1646-1660. (Level of Evidence 1A )

[38] May, S. & Comer, C. Is surgery more effective than non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis, and which non-surgical treatment is more effective? A systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2013, 99(1), 12-20. (Level of Evidence 1A)

[39] Minamide, A. et al. The natural clinical course of lumbar spinal stenosis: a longitudinal cohort study over a minimum of 10 years. J Orthop Sci (2013) 18:693–698. (Level of evidence 2)

[40] Mc Gregor et al. Rehabilitation Following Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. A Cochrane Review. Spine (2014) 39(13): 1044 – 1054. (Level of Evidence 1)