Multiple System Atrophy

Original Editors - Emily Nicklies from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Emily Nicklies, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, Dave Pariser, Wendy Walker, Elaine Lonnemann, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop and Amrita Patro

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) is defined as a sporadic, fatal, progressive, neurodegenerative adult-onset disorder. It is the second most common neurodegenerative movement disorder with an average annual incidence rate of 3 per 100000 person-years after Parkinson’s disease (PD)[1]. It can affect the

- Autonomic system causing autonomic failure, causing eg.fainting spells and problems with heart rate, erectile dysfunction, and bladder control.

- Basal ganglia causing parkinsonism, causing eg tremor, rigidity, and/or loss of muscle coordination as well as difficulties with speech and gait.

- Cerebellum causing ataxia [2]

The symptoms reflect the progressive loss of function and death of different types of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

Some of these features are similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease, and early in the disease course it often may be difficult to distinguish these disorders. The 2 minute video below gives a good introduction to MSA

Neuropathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Neuropathologically, MSA is characterized by putaminal, pontine and cerebellar atrophy.

The complexity of the neuropathological pattern correlates with the spectrum of the clinical phenotypes (several overlaps can be observed between MSA-P and MSA-C, each subtype is characterized by specific neuropathological features)

Subtypes

- MSA-P: denoted by severe striatonigral degeneration (part of the Basal Ganglia, see image to R).The dorsolateral caudal putamen and the caudate nucleus are severely affected, with a selective involvement of GABAergic medium spiny neurons . Substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons are also remarkably involved in the degenerative process and a trans-synaptic degeneration of striatonigral fibers has been proposed. Globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus are also implicated.

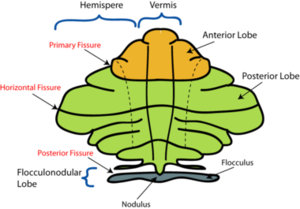

- MSA-C: this subtype is more severely characterized by the involvement of cerebellar vermis and hemispheres, dentate nucleus, inferior olive nuclei, pontine basis and cerebellopontine fibers. see image to R: Cerebellum

Both MSA-P and MSA-C are characterized by the involvement of other regions of the nervous system, including intermediolateral column of the spinal cord, dorsal nucleus of vagus and Onuf’s nucleus[4]. Motor and supplementary motor cortices are also implicated.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes of MSA are unknown; however, as for other neurodegenerative diseases, a complex interaction of genetic and environmental mechanisms seems likely.[5]

Research has suggested that MSA is characterized by a progressive loss of neuronal and oligodendroglial cells (myelin producing cells in CNS) in numerous sites in the CNS (basal ganglia, cerebellum). This damage is said to occur from the formation of glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCI’s).[6]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

MSA is an orphan disease with an incidence of up to 2.4 cases per 100 000 persons per year, while the prevalence may reach up to 7.8 patients per 100 000 population over the age of 40. The MSA‐P variant seems to be more common in the western hemisphere, whereas MSA‐C appears to be more frequent in Asia[7] .

There is about 1 living case of MSA in the population for every 40 cases of Parkinson’s disease, but because survival in MSA is shorter than for PD, about 1 new MSA case presents every year for about every 20 who present with PD.[7]

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

The symptoms reflect the progressive loss of function and death of different types of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. The initial symptoms of MSA are often difficult to distinguish from the initial symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and include: slowness of movement, tremor, or rigidity (stiffness); clumsiness or incoordination; impaired speech, a croaky, quivering voice; fainting or lightheadedness due to orthostatic hypotension; bladder control problems, such as a sudden urge to urinate or difficulty emptying the bladder[7].

Classification[edit | edit source]

MSA is classified by the most dominant symptom exhibited by the patient.

MSA-A:

- Autonomic dysfunction, primarily orthostatic hypotension, is present in approximately 75% of people with MSA.[8]

- Autonomic dysfunction commonly appears as postural/orthostatic hypotension associated with impaired or absent reflex tachycardia upon standing, bowel and bladder incontinence, thermoregulatory dysfunction, impotence, and hypohydrosis.[9],[6]

Figure 3: Autonomic Nervous System

MSA-P:

- When a parkinson-like movement dysfunction is the prominent feature, the disease is categorized as MSA-P. Parkinsonism has been identified as the initial feature in 46% of patients with MSA, but eventually over 80% of patients with MSA will develop parkinsonian features.[8]

- Characteristics of parkinsonism include bilateral involvement, bradykinesia, impaired writing, slurred speech, rigidity,[9]postural and rest tremor disequilibrium, and gait unsteadiness.[6]

MSA-C:

- When cerebellar dysfunction is more prominent, the disease is labeled as MSA-C. Over 50% of individuals with MSA will present with cerebellar dysfunction.[8]

- Cerebellar features that are characteristic of MSA initially manifest in the trunk and lower extremities, leading to disturbances in gait.[9]. These patients also display limb kinetic ataxia and scanning dysarthria, as well as cerebella ataxia.[9]

Associated Co-morbidities/Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

- Level of cognition and mental health[10]: Cognitive deficits occur in all cognitive domains. The impaired cognitive domains had a significant correlation with atrophy of frontotemporal cortical areas, insula, caudate, thalamus, and cerebellum. Impaired cognition is due to the pathology in both cortical and subcortical structures[1]; Emotional instability may occur later in the progression of the disease[8]; Depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and suicidal ideation may present in MSA; Cognitive impairment, particularly seen in executive function, may occur in up to 75% of patients

- Patients with MSA can have great difficulty switching attention from one stimulus to another,[9] with a decrease in goal-oriented cognitive ability.

2. Bowel and Bladder Dysfunction: Genitourinary dysfunctions are common symptoms (may include frequency, urgency, incontinence, and retention); Men may experience erectile difficulties early in the course of the disease; Constipation a common problem.[9]

3. Symptoms Occurring as the Disease Progresses: Dysphagia and dysarthria are symptoms late in the disease and should be treated by speech therapy.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

At this time, there are no specific symptoms, blood tests or imaging studies that distinguish MSA. Instead, doctors rely on a combination of symptom history, physical examination, and laboratory tests to evaluate the motor system, coordination, and autonomic function to arrive at a probable diagnosis[10].

The Mini-Mental State Examination, or MMSE, yielded 3% of participants showing signs of cognitive decline while a test called the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) categorized 41% of participants as being cognitively impaired[11]. The FAB is a cognitive test that incorporates several clinical assessments to screen for frontotemporal dementia (FTD),

Diagnostic Challenge[edit | edit source]

There is no “typical” presentation for this disorder, and MSA can often be masked by other diagnoses.

- Patients with MSA are most commonly misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. About 1/3 of people with MSA die while still misdiagnosed.[2]

- Only 25% of patients with MSA are correctly diagnosed at their first neurological visit. The correct diagnosis is usually established on an average of 4 to 5 years after the disease onset.[12]

- The distinction between MSA and parkinsonism is made by exclusion. If no autonomic or cerebellar signs are present, then the patient most likely has pure parkinsonism.[2]

- 90% of patients with MSA-P treated with Levodopa (L-Dopa) fail to show a sustained, long-term response.[12] This is a sign that this patient does not have pure parkinsonism, as L-Dopa is not effective.[2]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

MSA must be diagnosed on the basis of probability from the clinical presentation.[13]

To date there are no causative or disease-modifying treatments available and symptomatic therapies are limited. There is a strong need to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms in MSA in order to develop new therapeutic strategies options[5].

- Levodopa responsiveness has been reported initially in 83% of MSA-P patients, but the effect is usually transient, and only 31% showed a response for a period of 3.5 years. In some patients, motor fluctuations with wearing-off phenomena or off-bound dystonia were observed.

- Deep brain stimulation could not be recommended for MSA

- Active immunization against αS and combination with anti-inflammatory treatment may be promising therapeutic strategies. New strategies targeting αS are in progress, based on completed or ongoing interventional trials by the MSA Coalition.

Clinical presentation is not only important for diagnosis of MSA, but is also helpful in treatment. Since MSA is a variable condition, the most effective medical management is symptomatic treatment.[13] Current medical management includes pharmacological treatment. Medication is prescribed according to the subtype of MSA and the symptoms that are present.

Since MSA is a variable disorder and can present in many different ways. Therefore, treatment is symptomatic.

Pharmacological Treatment:

MSA-A

To manage autonomic symptoms, patients may consider options such as increasing salt intake or taking steroid hormones or other drugs that raise blood pressure. Sleep apnea devices known as CPAP (continuous, positive airway pressure) machines can help with breathing difficulties.[10]

- To treat orthostatic hypotension: (is defined as a fall in BP on standing of more than 20mmHg in SBP or 10 mmHg in DBP)[13] Drugs can be prescribed to enhance vasoconstriction and increase the blood volume, which will increase the blood pressure (Fludrocortisone and Midodrine).[2]

- To treat constipation stool softener medications are effective.[13]

- To treat urinary dysfunction pharmacological intervention do not adequately reduce post-void residual volume in patients with MSA, but anticholinergic agents like Oxybutynin can improve symptoms of hyper-reflexia.[12]

- To treat impotence: Sildenafil (25 to 75mg) may be successful in treating erectile failure.[12]

MSA-C

- There are no currently established pharmacological treatment strategies for cerebellar ataxia and pyramidal dysfunction.[12]

MSA-P

- Drugs used for Parkinson's disease may provide relief of muscle rigidity, slowness, and other motor symptoms for some MSA patients, though only in the earlier stages and with less effectiveness than for Parkinson's patients. Parkinson's drugs also can lower blood pressure and may worsen NOH symptoms, dizziness, and fainting episodes.[10]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapies offer drug-free tools for keeping muscles strong and flexible, helping prevent falls and other incidents that hasten disability. Encouraging mobility also lowers the risk of pulmonary embolism which can be fatal[10].

There is very little published literature on physical therapy or exercise intervention for patients with MSA.[8]

There is the most evidence concerning patients with MSA-A.[8]

Since majority of patients with MSA-A seem to experience orthostatic hypotension (OH), this is a main focus during a treatment session.[9][2] For effective strategies for OH see link.

Bowel and Bladder Treatment:

- Begin a urinary incontinence program if appropriate. Introducing exercises for the pelvic floor musculature in order to gain control/suppress urge, etc.

Gait/Mobility Training:

- Fit the patient for the most appropriate assistive device in order to gain independent mobility. This will depend upon the patient’s level of function and safety.

- If a wheelchair is most appropriate, ensure the chair is one that will best benefit their posture and mobility based upon the function of patient.

- As a PT, the need to promote independent functional mobility and optimal posture with safety in mind is most important.

Therapeutic Exercise/Activities:

- According to a study by Wedge, et al., gait training, transfer training, balance activities, and conditioning are necessary in reaching the goal of minimizing fatigue and risk for falling (safe transfers, etc.)[8]

- Resistance training has been proven to be effective in patients with MSA.

• Knee extensors and flexors, hip abductors and adductors, and ankle plantarflexors were targeted for resistance training. These muscle groups are chosen because of their importance to balance.[8]

• Following resistance training interventions, marked improvements are noted in the patient's gait pattern (increased consistency in maintaining good step height and length even when fatigued). Reduces festinating gait and other functional changes achieved. The patients improve transfer technique and posture (ie good head and trunk alignment in both sitting and standing). Also less frequency of falling.[8]

Additional Physical Therapy Advice:

Research reinforces the fact that since MSA is a variable disorder. Each patient with MSA will present differently, so it is difficult to give clear PT advice.

- Based upon a patient’s level of mobility and function, PT's should use their skills and knowledge to promote a safe and optimal environment for the patient.

- As a PT, maintaining strength and physiologic fitness as long as possible will be most valuable to the patient.[2]

- Education of the patient and family on benefits of PT is important for patient/family knowledge and compliance.

- Make PT goals realistic. Base the goals upon current function and take into consideration the activities most important to the patient.

- Since this is a progressive disorder, PT's must make sure to re-evaluate goals often to make sure they are appropriate.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

MSA often presents as the following disorders:

- Pure Parkinsonism[8],[9],[12],[13]

- Pure Autonomic Failure (PAF)[8],[9],[13],[12]

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy[14]

- Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration[15]

Prognosis and Outlook[edit | edit source]

Prognosis is currently guarded, with most MSA patients passing away from the disease or its complications within 6-10 years after the onset of symptoms. Nonetheless, there is reason for hope for MSA research goes on. Since the biology of MSA may be related to other neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's disease, it is possible that therapies designed for other conditions will also prove helpful for patients with MSA.[10]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

Wedge F. The Impact of Resistance Training on Balance and Functional Ability of a Patient with Multiple System Atrophy. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 2008;31:79-83.

The following case report documents the impact of a resistance-training program on a 68 year-old-female patient with a 2-year history of MSA.

Hemingway J, Franco K, Chmelik E. Shy-Drager Syndrome: Multisystem Atrophy With Comorbid Depression. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:73-6.

The following case report discusses the some of the struggles in the diagnostic process of a 48 year old man with MSA.

Mashidori T, Yamanishi T, Yoshida K, Sakakibara R ,Sakurai K, Hirata K. Continuous Urinary Incontinence Presenting as the Initial Symptoms Demonstrating Acontractile Detrusor and Intrinsic Sphincter Deficiency in Multiple System Atrophy. International Journal of Urology. 2007;14:972-74.

The following case report demonstrates how urinary incontinence can be the first symptoms of MSA in a 66-year-old female.

Goto K, Ueki A, Shimode H, Shinjo H, Miwa C, Morita, Y. Depression in Multiple System Atrophy: A Case Report. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2000;54:507-11. The following case report demonstrates how depression can be the first symptoms of MSA in a 56-year-old female.

Resources[edit | edit source]

SDS/MSA Support Group

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dash S, Mahale R, Netravathi M, Kamble NL, Holla V, Yadav R, Pal PK. Cognition in Patients With Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) and Its Neuroimaging Correlation: A Prospective Case-Control Study. Cureus. 2022 Jan 29;14(1). Available:https://www.cureus.com/articles/83909-cognition-in-patients-with-multiple-system-atrophy-msa-and-its-neuroimaging-correlation-a-prospective-case-control-study (accessed 14.3.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Lundy-Eckman, L. Neuroscience: Fundamentals for Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2002.

- ↑ MSA coalition. What is MSA available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVqiCgaLSf4&app=desktop (last accessed 17.1.2020)

- ↑ Compagnoni GM, Di Fonzo A. Understanding the pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy: state of the art and future perspectives. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2019 Dec;7(1):113. AVAILABLE FROM: https://actaneurocomms.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40478-019-0730-6 (last accessed 16.1.2020)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jellinger KA. Multiple system atrophy: an oligodendroglioneural synucleinopathy. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2018 Jan 1;62(3):1141-79 Available from.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5870010/ (last accessed 16.1.2020)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Diedrich A, Robertson D. Multiple System Atrophy. Vanderbilt University School of Medicine 2009. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1154583-overview (accessed on 24 Jan 2010).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Virtual strategy Multiple System Atrophy Epidemiology Forecast to 2030 Available: https://virtual-strategy.com/2020/07/16/multiple-system-atrophy-epidemiology-forecast-to-2030/ (accessed 14.3.2022)

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Wedge F. The Impact of Resistance Training on Balance and Functional Ability of a Patient with Multiple System Atrophy. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 2008;31:79-83.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Swan L, Dupont J. Multiple System Atrophy. Journal of Physical Therapy 1999;79:488-94.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 MSA Coalition. MSA what you need to know 4.4.2019. Available from: https://www.multiplesystematrophy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/What-You-Need-to-Know-9.4.19-DSC-AM-NV-Edits2.pdf (last accessed 17.1.2020)

- ↑ MAS coalition Depression and Cognitive Impairment in MSA Available:https://www.multiplesystematrophy.org/about-msa/depression-cognitive-impairment/ (accessed 14.3.2022)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Wenning GK, Braune S. Multiple System Atrophy: Pathophysiology and Management. CNS Drugs 2001;15:839-48.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Hardy, Joanne. Multiple System Atrophy: Pathophysiology, Treatment and Nursing Care. Nursing Standard 2008;22:50-6.

- ↑ O'Sullivan SS, Massey LA, Williams DR, Silveira-moriyama L, Kempster PA, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees, AJ. Clinical Outcomes of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Multiple System Atrophy. Brain. 2008;131:1362-72

- ↑ Hain TC. Multiple System Atrophy. 2010. http://www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/central/movement/msa.html (accessed on 5 april 2010).