Ataxia

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Ataxia refers to impaired coordination of voluntary muscle movement[1]. It refers to a physical finding and not a disease, and the underlying etiology should be investigated.

- Ataxia is usually caused by cerebellar dysfunction or impaired vestibular or proprioceptive afferent input to the cerebellum[1].

- Ataxia can have an insidious onset with a chronic and slowly progressive clinical course (eg, spinocerebellar ataxias of genetic origin) or have an acute onset, especially those ataxias resulting from cerebellar infarction, hemorrhage, or infection, which can have a rapid progression with catastrophic effects.[1]

- Ataxia manifests by a wide-based unsteady gait, errors of extremity trajectory or placement, errors in motor sequence or rhythm and/or by dysarthria. Tone is usually decreased and stretch reflexes may be “pendular.” Nystagmus, skew deviation, disconjugate saccades, and altered ocular pursuit can be present. Truncal instability and tremor of the body or head may occur, especially with cerebellar midline disorders.[2] More symptoms are discussed below.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Ataxia is usually caused by cerebellar dysfunction or impaired vestibular or proprioceptive afferent input to the cerebellum.

Any of the following can be implicated in pathology: Cerebellum, spinal cord, brain stem, vestibular nuclei, basal ganglia, thalamic nuclei, cerebral white matter, cortex (especially frontal), and peripheral sensory nerves. [2]

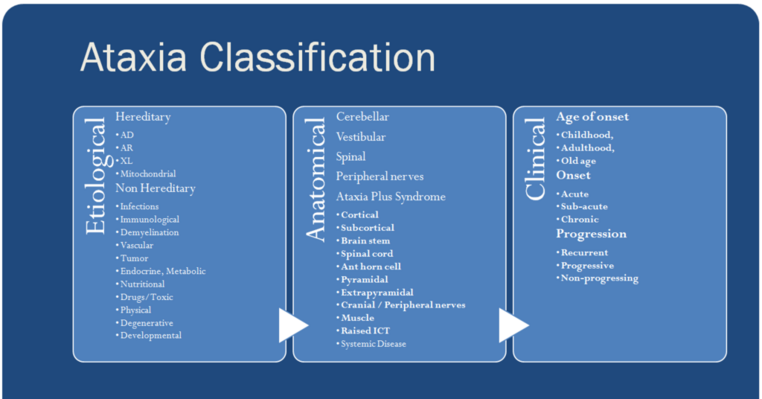

Classification of Disorders Causing Ataxia[edit | edit source]

Ataxia can be a manifestation of a variety of disease processes.

- Pure ataxia is rare in acquired ataxia disorders, and associated symptoms and signs almost always exist to suggest an underlying cause[1].

- The spectrum of hereditary degenerative ataxias is expanding[1]

- Attention should be addressed to those treatable and reversible etiologies, especially potentially life-threatening causes.

Mass Lesions[edit | edit source]

eg medulloblastoma, cystic astrocytoma, hemangioblastomas, and metastatic processes.

Vascular Disorders[edit | edit source]

Eg., Hemorrhage or infarction of cerebellum. A study found that ataxia severity is associated with the severity of the inferior cerebellar peduncle (ICP) injury in patients with cerebral infarct, suggesting that evaluation of the ICP using diffusion tensor tractography (DTT) as a useful tool for patients with ataxia after cerebral infarct[4].

Infectious and Post-infectious Processes[edit | edit source]

Eg Bacterial cerebellitis can occur with meningitis, penetrating trauma or extension of an epidural process, most commonly from temporal bone; Prion-associated encephalopathies include sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD); Acute cerebellitis (acute cerebellar ataxia) is a para-infectious disorder; Fisher syndrome, a Guillain-Barré variant, involves the peripheral and central nervous system.

Trauma[edit | edit source]

Gait instability may persist following cerebellar, vestibule, brain stem, or frontal lobe injury or with interruption of the frontopontocerebellar tract[2]. In acute trauma, or progressive post-traumatic ataxia, an expanding cyst or extra-axial hematoma should be considered.

Demyelinating Disorders[edit | edit source]

Ataxia is common in early and late multiple sclerosis, and intermittent ataxia may be the initial manifestation of MS in young children.[5]

Congenital Disorders[edit | edit source]

eg. Machado-Joseph Disease (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3), Dandy Walker Syndrome; Joubert syndrome; Ataxia can also occur with perinatal cerebral infarction and with congenital CNS infection.

Hereditary and Idiopathic Degenerative Processes[edit | edit source]

Hereditary ataxias are classified by the causative gene (when known) and their pattern of inheritance. eg spinocerebellar ataxias; Huntington Disease; Friedreich's ataxia; Fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome; Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a sporadic disorder that initially manifests after age 50 by ataxia (MSAc); Parkinsonism; Mitochondrial disorders are also associated with progressive ataxia.

Paroxysmal Disorders Associated with Ataxia[edit | edit source]

Intermittent ataxia has been associated with epilepsy, migraine, and high systemic fever in otherwise healthy children. Intermittent ataxia can also be associated with abnormalities in membrane calcium or potassium channel function, or with altered synaptic glutamate transport.

Spinal Cord and Peripheral Nerve-Related Ataxia[edit | edit source]

Spinal cord and/or nerve root disorders can produce ataxia.

Nutritional Deficiency, Toxins and Drugs[edit | edit source]

Solvent abuse or toxic exposure to solvents, methyl-mercury poisoning (Minamata disease), metronidazole (Flagyl)-induced cerebellar toxicity, central pontine myelinolysis (osmotic demyelination syndrome), leukoencephalopathy relating to the inhalation of heroin vapors, vitamin E deficiency, Alcoholism, Wernicke encephalopathy, and reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy can each be associated with the acute or chronic presentation of ataxia.[2]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Ataxia is usually caused by cerebellar dysfunction or impaired vestibular or proprioceptive afferent input to the cerebellum.

- Ataxia can have an insidious onset with a chronic and slowly progressive clinical course (eg, spinocerebellar ataxias of genetic origin)

- Ataxia can have an acute onset, especially those ataxias resulting from cerebellar infarction, haemorrhage, or infection, which can have a rapid progression with catastrophic effects.

- Ataxia can also have a subacute onset, as from infectious or immunologic disorders, which may have a limited window of therapeutic opportunities[1]

Symptoms and signs are often related to the location of the lesions in the cerebellum.

- Lateralized cerebellar lesions cause ipsilateral symptoms and signs, whereas diffuse cerebellar lesions give rise to more generalized symmetric symptoms. Lesions in the cerebellar hemisphere produce limb (appendicular) ataxia.

- Lesions of the vermis cause truncal and gait ataxia with limbs relatively spared.

- Vestibulocerebellar lesions cause disequilibrium, vertigo, and gait ataxia.

- Acute pathology in the cerebellum may initially produce severe abnormalities; this may recover remarkably with time and can become asymptomatic even when imaging shows persistent dramatic structural changes in the cerebellum.

- Chronic progressive ataxia is not only due to neurodegenerative or inherited cerebellar diseases but also neoplasms and chronic infections.

Common Symptoms of Ataxia include:

- Lack of coordination

- Slurred speech

- Trouble eating and swallowing

- Deterioration of fine motor skills

- Impaired motor learning[6]

- Eye movement abnormalities

- Tremors

- Heart problems

- Gait abnormalities - ataxia is evident by: [7][8] [9][10]

- shortened length of steps

- high step pattern

- decreased propulsion

- veering

- stumbling

- widened base of support

- irregular, variable foot placement

- deficits in multi-joint coordination

Terms Describing Ataxia[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists should be familiar with the specific ataxia terms and use them appropriately in documentation and communication with colleagues. It is important to understand the nomenclature because it often implies a certain ataxic disorder.

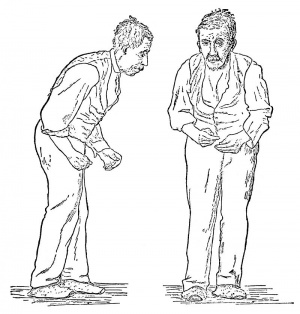

Stance. An impaired stance in the absence of motor weakness or gross involuntary movements is suggestive of cerebellar ataxia or sensory ataxia.

Gait ataxia. Gait ataxia results from incoordination of the lower extremities due to cerebellar pathology or loss of proprioceptive input. Patients often feel insecure and have to hold onto the wall or furniture and walk with feet apart. An increased gait disturbance when visual cues are removed (walking with eyes closed or in the dark) suggests a sensory or vestibular component to the ataxia. With cerebellar causes, the gait ataxia remains the same regardless of visual cues.

Sensory ataxia. Sensory ataxia is mainly reflected by gait disturbance. Subjects with sensory ataxia will have a positive Romberg sign. Subjects may walk with a high-stepping gait (due to associated motor weakness) or feet-slapping gait (to assist with sound-induced sensory feedback).

Truncal ataxia. Patients may present with truncal instability in the form of oscillation of the body while sitting (worse with arms stretched out in front) or standing (titubation).

Limb ataxia. Limb ataxia is often used to describe ataxia of the upper limbs resulting from incoordination and tremor and can be better described by functional impairment, such as clumsiness with writing,buttoning clothes, or picking up small objects. The patient has to slow down the movement to be accurate in reaching things. Limb ataxia can be lateralized with ipsilateral cerebellar lesions.

Dysdiadochokinesia/dysrhythmokinesis. Dysdiadochokinesia/dysrhythmokinesis is tested by rapidly alternating hand movements or tapping the index finger on the thumb crease. Impairment can be seen with irregularity of the rhythm and amplitude.

Intention tremor. Intention tremor results from instability of the proximal portion of the limb and is manifested by increasing amplitude of oscillation at the end of a voluntary movement. It is often tested by finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin maneuvers.

Dysmetria. The patient misses the targeted object either due to overshoot (hypermetria) or undershoot (hypometria). Dysmetria is often tested by a finger-chasing test and can be quantified by the distance (cm) that is missed.

Dysarthria/scanning speech. Often described by the patient or relatives as slurred speech. The patient’s speech is irregular and slow with unnecessary hesitation. Words are often broken into separate syllables

Nystagmus. Often occurs in cerebellar disease. Lateral gaze-evoked nystagmus is seen by slow drift toward midline followed by a fast phase of saccades to the eccentric position. Upbeat and downbeat nystagmus are defined by the rapid phase in the up or down direction.

Saccades. Saccade speed is typically normal in cerebellar disease but often an overshoot or undershoot (ocular dysmetria) is present, and is often followed by a corrective saccade in the appropriate direction.[1]

ASSESSMENT[edit | edit source]

HISTORY[edit | edit source]

History taking needs following consideration –

- Duration (Acute, subacute, chronic)

- Symmetry

- Rate of progression (static, episodic, progressive)

- Associated features (headache, vomiting, dystonia/chorea, proprioceptive dysfunction, visual deficits, auditory involvement)

- Medical history (infection, medications/intoxications, environmental exposures)

- Family history (suggest genetic disorder – autosomal recessive transmission/ autosomal dominant inheritance)

OBSERVATION[edit | edit source]

- Posture: widened base of support, may be trunk flexed and hands apart to maintain balance

- Gait: ataxic gait, High stepping gait, feet slapping gait

- Involuntary movement: Tremor

- Location(distal limb/truncal/head)

- Type(kinetic/postural)

- Duration(constant/intermittent)

- Intensity(fast/slow)

- Aggravating factor(movement/antigravity posture)

- Relieving factors: (rest/inactivity)

EXAMINATION[edit | edit source]

- HIGHER CENTRES: (consciousness, orientation, attention memory, cognition speech)

- CRANIAL NERVES : vestibular nerve for D/D

- SENSORY ASSESSMENT: superficial & deep sensation impaired/absent in sensory ataxia

- MOTOR ASSESSMENT

- TONE: hypotonia

- REFLEXES: hypo/areflexia

- ROM

- MUSCLE POWER: reduced strength

- CO-ORDINATION (EQUILIBRIUM, NON-EQUILIBRIUM): in co-ordination

- BALANCE (BBS & Rhomberg test): impaired balance

- GAIT (OBSERVATIONAL GAIT ANALYSIS-SPEED, SYMMETRY, LEVEL OF INDEPENDENCE)

- CARDIOVASCULAR (SUBMAXIMAL GRADED EXERCISE TESTING)

- FATIGUE : generalized fatigue/ asthenia

- FUNCTION AND DISABILITY (FIM, BARTHEL INDEX)

- SPECIFIC SCALES (INTERNATIONAL COOPERATIVE ATAXIA RATING SCALE, SCALE FOR ASSESSMENT AND RATING OF ATAXIA)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Ataxia is diagnosed using a combination of strategies that may include medical history, family history, and a complete neurological evaluation. Various blood tests may be performed to rule out other disorders. Genetic blood tests are available for many types of hereditary Ataxia.[11]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

A systematic review established that there was consistent evidence that physiotherapy improves, mobility, ataxia, improves function, and balance in patients with ataxia[12]. This can manifest in enhanced postural stability and less need for walking aids[13][14]. There is generally a consensus among specialists that early rehabilitation is helpful for patients with ataxia[15].

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

NB This describes the broad approach. look to individual conditions in physiopedia links for expansion (see above under causes)

Rehabilitation for people with ataxia may adopt a compensatory or restorative approach.

- Compensatory approach - includes Introduction to Orthotics and devices, movement retraining, reducing the degrees of freedom and optimising the environment. Valuable for teaching people practical, everyday strategies and ways of managing the condition. It may be particularly important for those with severe upper limb tremor.

- Restorative approaches aim to improve function by improving the underlying impairment. Despite cerebellar damage, some improvement in symptoms can occur with practice in people with chronic and progressive conditions.

Physiotherapists will employ a combination of restorative and compensatory approaches guided by the patient’s clinical presentation and context.

Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy can improve gait, balance and trunk control for people with ataxia, and can reduce activity limitations and support increased participation.

- The prevention of falls is important to consider in patients with progressive ataxia given their high frequency and fall-related injuries being common. In one study (n=13), 84% of patients fell at least once over a year[16].

- Careful assessment is required to avoid falls.

- For people with cerebellar dysfunction, dynamic task practice that challenges stability, explores stability limits and aims to reduce upper-limb weight bearing seems an important intervention to improve gait and balance.

- Strength and flexibility training may be indicated.

- Therapeutic equipment is often provided to support function.

- Intensity of training seems to be important as studies have shown that higher training intensities are associated with greater improvements in clinical outcome.[17]

- There is some evidence to suggest that improvement is greater in people with less severe ataxia and it is also related to the ability to learn the task.[17]

- Targeted coordination and gait training over a four-week period resulted in improvements in people with cerebellar ataxia as measured by the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA ) that was sustained after one year. Daily training improved outcome. This particular training showed a more sustained improvement in people with cerebellar dysfunction compared to people with afferent ataxias such as Friedreich’s ataxia and sensory ataxic neuropathy.[17]

- Balance training exercises undertaken in front of standardised moving visual images resulted in improvements in balance scores in some patients with SCA6 (a pure cerebellar ataxia) in a pilot trial but results were mixed.[17]

Specific Interventions for Balance and Gait[edit | edit source]

I. Video-game based coordinative training

eg Intensive coordination training using whole-body controlled videogames can be an effective and motivational therapy for children with progressive ataxia

II. Treadmill training

Treadmill training can be an effective intervention for people with ataxia due to brain injury. Intensity and duration of training seem to be significant factors. Consistent intensive training over many months combined with over-ground training may be required. This intervention has not been tested in people with progressive ataxias.

III. Visually guided stepping

Oculomotor and locomotor control systems interact during visually guided stepping in that the locomotor system depends on information from the oculomotor system during functional mobility for accurate foot placement. Marked improvements in oculomotor and locomotor performance have been seen following eye movement rehearsal in a small study in patients with mild cerebellar degeneration. Rehearsal of intended steps through eye movement alone, i.e. looking at foot target placement for each step, before negotiating a cluttered room, might improve performance and safety. This simple strategy, although task specific and short lived in nature, is promising and relatively quick and easy to apply in a functional setting.[17]

IV. Balance and mobility aids

- No studies have specifically evaluated the role of balance and mobility aids for people with ataxia. Clinical experience suggests walking aids should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

- In terms of postural control, somatosensory cues from the fingertips – using light touch contact or a walking aid as a means of balance – can provide a powerful reference orientation even when contact force levels are inadequate to provide physical support for the body. Some individuals with ataxia find light touch contact more useful as a strategy than a conventional walking aid.

- Walking aids also have the potential to compromise the ability to respond to balance disturbances through impeding lateral compensatory stepping and can thus affect safety, hence ensure the appropriate walking aid is recommended for each patient.[17]

Specific Interventions for Spasticity[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy has a vital role to play in educating patients and carers in correct posture, muscle use and the avoidance of spasticity triggers such as pain and infection.

- Muscle lengthening to maintain and improve range of movement and prevent the formation of contractures. eg physical exercises which antagonize the overactive spastic muscle and also improve muscle strength; passive stretching by the therapist or carer; or physical positioning techniques. Active exercise is generally more effective than passive exercise if the patient is able; increased fitness can also reduce fatigue and permit further exercises.

- Positioning eg splinting, casting, orthoses, standing or the use of weights, resistive devices, wedges, cushions or T-rolls. More prolonged splinting can involve firm materials such as metal or plastic, or softer supportive materials such as foam or sheepskin. Orthoses should be of good quality, well-fitted and prepared by a specialist.[17]

Exercises[edit | edit source]

In general, people with ataxia should be encouraged to exercise as part of health promotion (as long as risk factors and health and safety considerations have been assessed). Exercise should be tailored towards what appeals most to participants and may involve exploring several different options as well as building motivation and sustainability into the exercise prescription. eg hydrotherapy, general fitness training.[17]

Some important points for exercises:

- The positioning should be comfortable.

- Dosage of exercises are generally decided according to the severity of each case because it can vary from patient to patient.

- Generally, the number of sessions are two times a day.

- Two-three sets of exercises with an interval of 5-6 minutes in between the sets, in a controlled manner is appreciated.

- Progression can be like, starting with 2-3 exercises per session with repetition of 8-10, and when the task became easy one can increase the repetition to 12-15 or can add few more exercises to the program.

- A 2014 study recommended exercises for balance training, as they found it improved walking ability in patients with ataxia.[18]

Following are the few exercises that can be added to one's treatment plan:

- Lying bent knee rotation: this exercise is focuses on segmental movement of lower limb and will help in bed movement and transfers. It can be done by lying face up with both the knees bent, hip width apart and feet flat, arms can be positioned out wide away from the body. Now slowly begin to let both the knees rotate from one side of the body to the other side.(trying keep upper body and back flat).

- Kneeling press up: this can be start in upright kneeling position with knees under hip and with arms at the sides, slow movement from high kneeling position to hip straight body upright, to a low kneeling position hip movement down to rest on heels.

- Quadruped weight shifting: start positioned with hand under kneeling and knees under hips and the spine is neutral. slowly reach an arm forward to shoulder height, then begin to extend the opposite-side leg backward to hip height. balance for a moment before lowering both the arm and leg to the ground.

- Vestibular ball: vestibular ball can be used for balance exercises, the external support of therapist or the person helping to exercise, sitting upright on an exercise ball with feets apart,the legs are then locked by the therapist in order to avoid any fall as the patient is have balancing problems. smoothly begins to move the upper body to the right and then to the left,allow the weight of the trunk to shift from one side to another.

- Standing heel to toe balance: standing upright position one foot in front of the other so heel of the front foot is touching the toes of the back foot, as if standing on the tightrope.

Wheelchair Seating[edit | edit source]

Wheelchairs rank among the most important therapeutic devices used in rehabilitation. Despite a lack of research studies, clinical observation suggests that powered wheelchair mobility with appropriate postural support is an option to provide people with ataxia with a means of independent mobility.[17]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Ashizawa T, Xia G. Ataxia. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2016 Aug;22(4 Movement Disorders):1208. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5567218/ (last accessed 8.2.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Brunberg JA. Ataxia. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2008 Aug 1;29(7):1420-2. Available from:http://www.ajnr.org/content/29/7/1420 (last accessed 8.2.2020)

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Medicine. What is ataxia? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DTfJXPFLOA0 [last accessed 30/09/2022]

- ↑ Jang SH, Do Lee H. Relationship between ataxia and inferior cerebellar peduncle injury in patients with cerebral infarct. Medicine. 2020 Feb 1;99(9):e19344.

- ↑ Pavone P, Praticò AD, Pavone V, Lubrano R, Falsaperla R, Rizzo R, Ruggieri M. Ataxia in children: early recognition and clinical evaluation. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2017 Dec;43:1-9. [1]

- ↑ Morton SM, Bastian AJ. Cerebellar contributions to locomotor adaptations during splitbelt treadmill walking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006 Sep 6;26(36):9107-16.

- ↑ Bastian AJ. Moving, sensing and learning with cerebellar damage. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2011 Aug 1;21(4):596-601.

- ↑ Crowdy KA, Hollands MA, Ferguson IT, Marple-Horvat DE. Evidence for interactive locomotor and oculomotor deficits in cerebellar patients during visually guided stepping. Experimental brain research. 2000 Dec;135:437-54.

- ↑ Mark H, Steve GM. Physiologic studies of dysmetria in patients with cerebellar deficits. Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 1993 May;20(S3):S83-92.

- ↑ Palliyath S, Hallett M, Thomas SL, Lebiedowska MK. Gait in patients with cerebellar ataxia. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 1998 Nov;13(6):958-64.

- ↑ NAF What is ataxia Available from:https://ataxia.org/what-is-ataxia/ (last accessed 9.2.2020)

- ↑ Milne SC, Corben LA, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Delatycki MB, Yiu EM. Rehabilitation for individuals with genetic degenerative ataxia: a systematic review. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2017 Jul;31(7):609-22.

- ↑ Gill-Body KM, Popat RA, Parker SW, Krebs DE. Rehabilitation of balance in two patients with cerebellar dysfunction. Physical Therapy. 1997 May 1;77(5):534-52.

- ↑ Balliet R, Harbst KB, Kim D, Stewart RV. Retraining of functional gait through the reduction of upper extremity weight-bearing in chronic cerebellar ataxia. International rehabilitation medicine. 1986 Jan 1;8(4):148-53.

- ↑ Chien HF, Zonta MB, Chen J, Diaferia G, Viana CF, Teive HAG, Pedroso JL, Barsottini OGP. Rehabilitation in patients with cerebellar ataxias. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022 Mar;80(3):306-315. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X-ANP-2021-0065. PMID: 35239817; PMCID: PMC9648943.

- ↑ Fonteyn EM, Schmitz-Hübsch T, Verstappen CC, Baliko L, Bloem BR, Boesch S, Bunn L, Giunti P, Globas C, Klockgether T, Melegh B. Prospective analysis of falls in dominant ataxias. European neurology. 2013 Nov 7;69(1):53-7.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 Ataxia org. Ataxia- for physiotherapists Available from:https://www.ataxia.org.uk/news/physiotherapy (last accessed 9.2.2020)

- ↑ Keller JL, Bastian AJ. A home balance exercise program improves walking in people with cerebellar ataxia. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014 Oct;28(8):770-8. doi: 10.1177/1545968314522350. Epub 2014 Feb 13. PMID: 24526707; PMCID: PMC4133325.