Guillain-Barre Syndrome

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Surinder Singh, Garima Gedamkar, Redisha Jakibanjar, Jonathan Wong, Andeela Hafeez, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Wendy Walker, Rachael Lowe, Nitisha Sethi, Admin, Eugenie Lamprecht, Evan Thomas, Chelsea Mclene, Claire Knott, Alex Kin Ming NG, WikiSysop, Wout Van Hees, Sai Kripa, Oyemi Sillo, Naomi O'Reilly and Mason Trauger

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a condition characterised by the autoimmune destruction of the peripheral sensory system[1]. It can involve sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves. There occurs temporary inflammation and demyelination of peripheral nerve myelin sheaths resulting in axonal degeneration. It is the most common cause of quickly progressive flaccid paralysis. It is believed to be one of a number of related conditions, all sharing a similar underlying autoimmune abnormality, as a group known as anti-GQ1b IgG antibody syndrome.

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is considered the chronic counterpart to Guillain-Barré syndrome.[2]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Most cases of GBS are preceded by upper respiratory tract infections or diarrhoea one to three weeks prior to their onset. The most common infections causing GBS include Campylobacter jejuni, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Cytomegalovirus[4]. Campylobacter jejuni is responsible for about a third of GBS cases, and the ensuing GBS is usually more severe than that due to other causes[4]. Recent infection with Campylobacter jejuni is strongly associated with developing AIDP or AMAN[5]. Molecular imitation by the bacterial agents is thought to cause the autoimmunity with the development of anti-GQ1b IgG antibodies. GBS often presents (70% of patients) within 1-6 weeks of prior illness[6].

Alternative predisposing factors include recent surgery, lymphoma, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Incidence: The annual incidence of GBS in the USA is 1.2-3 per 100,000 inhabitants[7]; GBS has been reported throughout the world. Most studies show annual incidence figures similar to those in the United States[8].

- Age: The annual mean rate of hospitalizations in the United States related to GBS increases with age, being 1.5 cases per 100,000 population in children under 15 years of age, and peaking at 8.6 cases per 100,000 population in 70-79 year olds[9]

- Men are more likely to develop Guillain–Barré syndrome than women; the relative risk for men is 1.78 compared to women[10].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of GBS is complex. GBS is considered to be an autoimmune disease triggered by a preceding bacterial or viral infection. Campylobacter jejuni, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are commonly identified antecedent pathogens.

The body's immune system begins to attack the body itself,[11] The immune response causes a cross-reaction with the neural tissue. When myelin is destroyed, destruction is accompanied by inflammation. These acute inflammatory lesions are present within several days of the onset of symptoms. Nerve conduction is slowed and may be blocked completely. Even though the Schwann cells that produce myelin in the peripheral nervous system are destroyed, the axons are left intact in all but the most severe cases. After 2-3 weeks of demyelination, the Schwann cells begin to proliferate, inflammation subsides, and re-myelination begins.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typically, GBS symptoms present 2-4 weeks after a relatively benign gastrointestinal or respiratory illness. The first neurological sign of GBS is usually paresthesias of the toes, followed by a sudden onset (hours to days) of symmetrical, progressive bilateral weakness and sensory loss distal to proximal throughout the body. This dysfunction may impact the muscles of respiration, and even cranial nerves cranial nerves. In most forms of GBS, there is a greater loss of motor function than sensory function. [12]

Pain is an often under-recognised symptom of GBS[13]. In a study following 55 patients with GBS, 89% reported pain, with 47% grading it as severe[14]. Pain was described as deep and achy in the lower back and legs, and patients also described dysesthesia in their extremities[14]. The pain improved with time, but the dysesthesia remained in a small group of patients[14]. Another study suggested that pain may last up to 2 years for some patients[15].

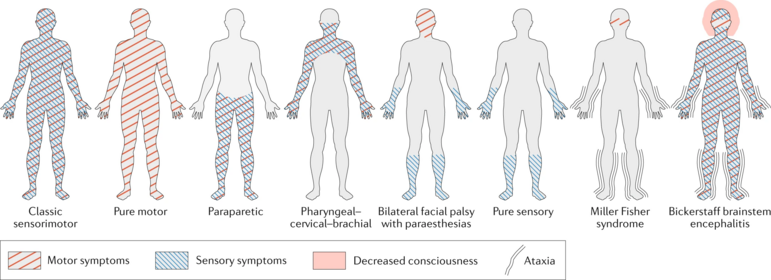

GBS can be split up into two types according to electrophysiologic and pathologic features: the demyelinating type, and the axonal type[16]. Subtypes in line with these include:

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP): most common form (60-90%)

- Axonal subtypes: acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) (historically Chinese paralytic syndrome); acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN)

- Regional GBS syndromes: Miller Fisher variant (MFS/MFV), characterised by ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and areflexia without weakness, anti-GQ1b antibodies are present in most cases; polyneuritis cranialis.[7]

Symptoms Progression[edit | edit source]

Antecedent Illness: Upper respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses are the most commonly reported conditions[17]. Symptoms generally have resolved by the time the patient presents with the neurological condition.

GBS Symptom progression: The mean time to the peak of symptoms is 12 days (from 1st neurological symptoms), with 98% of patients reaching a peak by 4 weeks. A plateau phase of persistent, unchanging symptoms then ensues, followed days later by gradual symptom improvement[18]. Recovery usually begins 2-4 weeks after the progression ceases[19]. The mean time to clinical recovery is 200 days.

Overall, most patients with GBS do well, with 85% of patients recovering independent ambulation; however, 20% of patients continue with morbidity[1]. More than 80% of patients achieve independent ambulation within six months[20].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acute peripheral neuropathies

- Toxic: thallium, arsenic, lead, n-hexane, organophosphate

- Drugs: amiodarone, perhexiline, gold

- Alcohol

- Porphyria

- Systemic vasculitis

- Poliomyelitis

- Diphtheria

- Tick paralysis

- Critical illness polyneuropathy

- Disorders of Neuromuscular Transmission

- Botulism

- Myasthenia gravis

- Central Nervous System Disorders

- Basilar artery occlusion

- Acute cervical transverse myelitis

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) is considered a clinical diagnosis and a diagnosis can be made at the bedside in most cases. For atypical cases or unusual subtypes, ancillary testing can be useful.

These include:

- Cerebrospinal fluid investigation: It will elevated at some stage of the illness but remains normal during the first 10 days. There may be lymphocytosis (> 50000000 cells/L).

- Electrophysiological studies: it includes nerve conduction studies and electromyography. They are normal in the early stages but show typical changes after a week or so with conduction block and multifocal motor slowing, sometimes most evident proximally as delayed F-waves.

The only way to classify a patient as having the axonal or nonaxonal type is electrodiagnostically. - Further investigative procedures can be undertaken to identify an underlying cause

For example:- Chest X-ray , stool culture and appropriate immunological tests to rule out the presence of cytomegalovirus or mycoplasma

- Antibodies to the ganglioside GQ1b for Miller Fisher Variant.

- MRI

- Lumbar Puncture: Most, but not all, patients with GBS have an elevated CSF protein level (>400 mg/L), with normal CSF cell counts. Elevated or rising protein levels on serial lumbar punctures and 10 or fewer mononuclear cells/mm3 strongly support the diagnosis.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Guillain-Barré syndrome can be a devastating disorder because of its sudden and unexpected onset. In addition, recovery is not necessarily quick. Typically, improvement occurs after a number of weeks to months, although there is significant mortality (3-10%).[2]

The majority of people recover completely or nearly completely[21]. However, some have mild residual effects such as foot drops or abnormal feeling in the feet and hands that persists for two years or more. Persistent fatigue and pain may present. Fewer than 15 percent have a substantial long-term disability severe enough to need a cane, walker or wheelchair.

Predictive factors for poor outcome for GBS include[22][23][24]:

- Older age

- Cranial nerve impairment

- Recent surgery

- Elevated level of liver enzymes

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure at admission

- Uroschesis

- Fever

- Ventilator support during hospitalization

- Disorder of consciousness

- Absence of preceding respiratory infection

Management[edit | edit source]

There is no known cure for Guillain-Barré syndrome, but therapies that lessen the severity of the illness and accelerate the recovery in most patients exist. GBS is primarily managed with Intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis along with supportive measures, which can hasten recovery.[2]

Further Medical Management Can Be Done According to the Symptoms and the Complications[edit | edit source]

- Supportive Care

- ICU monitoring

- Basic medical management often determines mortality and morbidity.

- Ventilatory Support

- Atelectasis leads to hypoxia.

- Hypercarbia later finding; arterial blood gases may be misleading.

- Vital capacity, tidal volume and negative inspiratory force are the best indicators of diaphragmatic function.

- Progressive decline of these functions indicates an impending need or ventilatory assistance. Mechanical ventilation usually required if VC drops below about 14 ml/kg; ultimate risk depends on age, the presence of accompanying lung disease, aspiration risk, and assessment of respiratory muscle fatigue.

- Atelectasis treated initially by incentive spirometry, frequent suctioning, and chest physiotherapy to mobilize secretions.

- Intubation may be necessary for patients with substantial oro-pharyngeal dysfunction to prevent aspiration.

- Tracheostomy may be needed in patients intubated for 2 weeks who do not show improvement.

- Autonomic Dysfunction

- Autonomic dysfunction may be self-limited; do not over-treat.

- Sustained hypertension managed by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or beta-blocking agent. Use short-acting intravenous medication for labile hypertension requiring immediate therapy.

- Postural hypotension treated with fluid bolus or positioning.

- Urinary difficulties may require intermittent catheterization.

- Nosocomial Infections Usually Involve Pulmonary and Urinary Tracts.

- Occasionally central venous catheters become infected.

- Antibiotic therapy should be reserved for those patients showing clinical infection rather than the colonization of fluid or sputum specimens.

- Venous Thrombosis Due to Immobilization Poses a Great Risk of Thromboembolism

- Prophylactic use of subcutaneous heparin and compression stockings.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown that exercise can positively influence outcomes such as mobility, fatigue levels and even mental function in GBS patients[25][26]. One study suggests that high-intensity exercise induces greater improvement in FIM motor scores, compared to lower intensity[27]. However, over-exercise for patients with GBS of partially denervated muscles can cause further damage, including a loss of functioning motor units[28], hence the need to closely monitor exercise intensity to avoid over-exercising partially denervated motor units[29][30].

Aims of physiotherapy management are:

- Regain the patient's independence with everyday tasks.

- Retrain normal movement patterns.

- Improve patient's posture.

- Improve the balance and coordination

- Maintain clear airways

- Prevent lung infection

- Support joint in functional position to minimize damage or deformity

- Prevention of pressure sores

- Maintain peripheral circulation

- Provide psychological support for the patient and relatives.

A tri-phasic approach was suggested for physical therapy management when comparing to disease progression:

- Acute/Ascending Phase (first 2-3 weeks): prevention of complications of immobilization (contracture, pressure injury, etc.), supporting pulmonary function, and pain management.

- Plateau Phase: increasing upright posturing, improving pulmonary function while avoiding fatigue/overexertion, gentle stretching and active-assisted and active range of motion as tolerated for gradual improvements in mobility.

- Recovery/Descending Phase (~2-4 weeks after the plateau phase): increased upright posturing and weight-bearing, encouraging a high-intensity rehabilitation approach utilizing active resistance training and neuromuscular facilitation techniques. [31]

Respiratory Care[edit | edit source]

The common respiratory complications in the rehabilitation setting include incomplete respiratory recovery including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, restrictive respiratory disease (pulmonary scarring, pneumonia), and tracheitis from chronic intubation and respiratory muscle insufficiency. Sleep hypercapnia and hypoxia, which worsens during sleep can be the result of a restrictive pulmonary function.[32][33]

Treatment methods are:

- Nighttime saturation records with a pulse oximeter and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) may be indicated for the patients.

- Physical therapy measures (chest percussion, breathing exercises, resistive inspiratory training) may be required to clear respiratory secretions to reduce the work of breathing.

- Special weaning protocol to prevent over-fatigue of respiratory muscles can be recommended for more severe patients with tracheostomy. Patients with cranial nerve involvement need extra monitoring as they are more prone to respiratory dysfunction.

- Patients should be encouraged to cease smoking.

- Posturally drain areas of lung tissues, 2-hourly turning into supine or side-lying positions.

- 2-4 litre anesthetic bag can be used to enhance chest expansion. Therefore, 2 people are necessary for this technique, one to squeeze the bag and another to apply chest manipulation.

- Rib springing to stimulate cough.

- After the removal of a ventilator and adequate expansion, effective coughing must be taught to the patient.

Maintain Normal Range of Movement[edit | edit source]

Gentle passive movements through full ROM at least three times a day especially at the hip, shoulder, wrist, ankle, and feet.

Orthoses[edit | edit source]

Use of light splints (eg. using PLASTAZOTE) may be required for the following purpose listed below:

- Support the peripheral joints in a comfortable and functional position during flaccid paralysis.

- To prevent abnormal movements.

- To stabilize patients using sandbags, and pillows.

Prevention of Pressure Sores[edit | edit source]

Change in patient's position from supine to side-lying after every 2 hours. If the sores have developed then UVR or ice cube massage to enhance healing.

Maintenance of Circulation[edit | edit source]

- Passive movements

- Effleurage massage to lower limbs.

Relief of Pain[edit | edit source]

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

- Massage with passive ROM

- The patient can demonstrate increased sensitivity to light touch, a cradle can be used to keep the bedsheet away from the skin. Low-pressure wrapping or snug-fitting garments can provide a way to avoid light touch.

- Reassurance and explanation of what to expect can help in the alleviation of anxiety that could compound the pain.

Strength and Endurance training[edit | edit source]

Strengthening exercises can involve isometric, isotonic or isokinetic exercises, while endurance training involves progressively increasing the intensity and duration of functional activities such as walking or stair-climbing[34].

Functional training[edit | edit source]

Retraining of dressing, washing, bed mobility, transfers, and ambulation activities comprise a big part of the rehabilitation process. Balance and proprioception retraining in all these functional activities should also be included, while motor control can be achieved by doing Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) techniques[34].

Research shows that high-intensity relative to lower intensity exercise significantly reduced disability in patients with GBS, as measured with the FIM (p<0.005, r=0.71). Overall, various types of exercise programmes improve physical outcomes such as functional mobility, cardiopulmonary function, isokinetic muscle strength, and work rate and reduce fatigue in patients with GBS[35][36].

Assistive devices[edit | edit source]

Assistive devices such as wheelchairs, walking sticks and quadrupeds should be made available to individuals if required in order to facilitate safe and effective ambulation[34].

According to Bensman (1970), the following four guidelines are to be followed for the prescription of exercises:

- Use short periods of non-fatiguing exercises matched to the patients strength.

- Progression of the exercise should be done only if the patient improves or if there is no deterioration in status after a week.

- Return the patient to bed rest if a decrease in muscle strength or function occurs.

- The objective should be directed not only at improving function but also at improving strength.

*A study of 35 patients (27 with classic GBS and 8 with acute motor axonal neuropathy [AMAN]), reported GBS-related deficits included: neuropathic pain requiring medication therapy (28 patients) *foot drop necessitating ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) use (21 patients) *locomotion difficulties requiring assistive devices (30 patients) *At 1-year follow-up, the authors found continued foot drop in 12 of the AFO patients. However, significant overall functional recovery had occurred within the general cohort[37] (LoE 1B).

Nehal and Manisha (2015) suggest a functional goal-oriented multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for daily 1 hour sessions for 12 weeks.

Additional Read[edit | edit source]

Case Study: Guillain-Barre Syndrome (Sub-Acute)

Guillain-Barré Case Study: Marie

Guillain-Barré Case Study: David

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nguyen TP, Taylor RS. Guillain-Barre Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Radiopedia Guillain-Barré syndrome Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/guillain-barre-syndrome-2 (accessed 25.9.2022)

- ↑ Osmosis Guillain-Barre Syndrome - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYNAzJqJKd8

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Finsterer J. Triggers of Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Campylobacter jejuni Predominates. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Nov 17;23(22):14222. doi: 10.3390/ijms232214222. PMID: 36430700; PMCID: PMC9696744.

- ↑ Liu GF, Wu ZL, Wu HS, Wang QY, Zhao-Ri GT, Wang CY, Liang ZX, Cui SL, Zheng JD. A case-control study on children with Guillain-Barre syndrome in North China. Biomedical and environmental sciences: BES. 2003 Jun 1;16(2):105-11.

- ↑ Koga M, Yuki N, Hirata K. Antecedent symptoms in Guillain-Barré syndrome: an important indicator for clinical and serological subgroups. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001 May;103(5):278-87. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.103005278.x. PMID: 11328202.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alshekhlee A, Hussain Z, Sultan B, Katirji B. Guillain-Barré syndrome: incidence and mortality rates in US hospitals. Neurology. Apr 29 2008;70(18):1608-13

- ↑ Kushnir M, Klein C, Pollak L, Rabey JM. Evolving pattern of Guillain-Barre syndrome in a community hospital in Israel. Acta Neurol Scand. May 2008;117(5):347-50

- ↑ Prevots DR, Sutter RW. Assessment of Guillain-Barré syndrome mortality and morbidity in the United States: implications for acute flaccid paralysis surveillance. J Infect Dis. Feb 1997;175 Suppl 1:S151-5

- ↑ Sejvar JJ, Baughman AL, Wise M, Morgan OW. Population incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(2):123-33.

- ↑ http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/gbs/detail_gbs.htm

- ↑ Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants. Neurol Clin [Internet]. 2013;31(2):491–510.

- ↑ Umapathi T, Yuki N. Pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2011;11(3):335–9.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Moulin DE, Hagen N, Feasby TE, Amireh R, Hahn A. Pain in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurology. 1997 Feb;48(2):328-31.

- ↑ Forsberg A, Press R, Einarsson U, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Holmqvist LW, Network Members of the Swedish Epidemiological Study Group. Impairment in Guillain–Barré syndrome during the first 2 years after onset: a prospective study. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2004 Dec 15;227(1):131-8.

- ↑ Lv J, Zhaori G. Collaborative studies of U.S.-China neurologists on acute motor axonal neuropathy. Pediatr Investig. 2022 Mar 22;6(1):1-4. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12316. PMID: 35382424; PMCID: PMC8960912.

- ↑ Nelson L, Gormley R, Riddle MS, Tribble DR, Porter CK. The epidemiology of Guillain-Barré Syndrome in U.S. military personnel: a case-control study. BMC Res Notes. Aug 26 2009;2:171

- ↑ Hughes RA, Rees JH. Clinical and epidemiologic features of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. Dec 1997;176 Suppl 2:S92-8.

- ↑ El Mhandi L, Calmels P, Camdessanché JP, Gautheron V, Féasson L. Muscle strength recovery in treated Guillain-Barré syndrome: a prospective study for the first 18 months after onset. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Sep 2007;86(9):716-24

- ↑ van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain-Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014 Aug;10(8):469-82. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.121. Epub 2014 Jul 15. PMID: 25023340.

- ↑ Miller-Fisher Syndrome https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/miller-fisher-syndrome/

- ↑ Wen P, Wang L, Liu H, Gong L, Ji H, Wu H, Chu W. Risk factors for the severity of Guillain-Barré syndrome and predictors of short-term prognosis of severe Guillain-Barré syndrome. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 2;11(1):11578. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91132-3. PMID: 34079013; PMCID: PMC8172857.

- ↑ Seta T, Nagayama H, Katsura K, Hamamoto M, Araki T, Yokochi M, Utsumi K, Katayama Y. Factors influencing outcome in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: comparison of plasma adsorption against other treatments. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005 Oct;107(6):491-6. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.12.019. PMID: 16202823.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Wang Y. Prognostic factors of Guillain-Barré syndrome: a 111-case retrospective review. Chin Neurosurg J. 2018 Jun 18;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s41016-018-0122-y. PMID: 32922875; PMCID: PMC7398209.

- ↑ Bussmann JB, Garssen MP, van Doorn PA, Stam HJ. Analysing the favourable effects of physical exercise: relationships between physical fitness, fatigue and functioning in Guillain-Barré syndrome and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2007 Mar;39(2):121-5.

- ↑ Simatos Arsenault N, Vincent PO, Yu BH, Bastien R, Sweeney A. Influence of Exercise on Patients with Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Physiother Can. 2016;68(4):367-376. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2015-58. PMID: 27904236; PMCID: PMC5125499.

- ↑ Khan F, Pallant JF, Amatya B, Ng L, Gorelik A, Brand C. Outcomes of high-and low-intensity rehabilitation programme for persons in chronic phase after Guillain-Barré syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011 May 30;43(7):638-46.

- ↑ Herbison GJ, Jaweed MM, Ditunno Jr JF. Exercise therapies in peripheral neuropathies. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1983 May 1;64(5):201-5.

- ↑ Fisher TB, Stevens JE. Rehabilitation of a marathon runner with Guillain-Barre syndrome. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2008 Dec 1;32(4):203-9.

- ↑ Drory VE, Bronipolsky T, Bluvshtein V, Catz A, Korczyn AD. Occurrence of fatigue over 20 years after recovery from Guillain–Barré syndrome. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2012 May 15;316(1-2):72-5.

- ↑ Martin ST, Kessler M. Neurologic interventions for physical therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier - Health Sciences Division; 2020.

- ↑ Guillain‐Barré syndrome Management of respiratory failure Allan H. Ropper, MD and Susan M. Kehne, MD http://www.neurology.org/content/35/11/1662 (Level Of Evidence 4)

- ↑ Khan F, Amatya B. Rehabilitation interventions in patients with acute demyelinating inflammatory polyneuropathy: a systematic review. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2012 Sep;48(3):507-22.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Nehal S, Manisha S. Role of physiotherapy in Guillain Barre Syndrome: A narrative review. Int J Heal. Sci. & Research: 5 (9): 529. 2015;540.

- ↑ Simatos Arsenault N, Vincent PO, Yu BH, Bastien R, Sweeney A. Influence of exercise on patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. 2016;68(4):367-76.

- ↑ Khan F, Pallant JF, Amatya B, Ng L, Gorelik A, Brand BC, Brand C. Outcomes of high-and low-intensity rehabilitation programme for persons in chronic phase after Guillain-Barré syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011 Jun 5;43(7):638-46.

- ↑ Gupta A, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Murali T. Guillain-Barre Syndrome – rehabilitation outcome, residual deficits and requirement of lower limb orthosis for locomotion at 1-year follow-up. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(23):1897-902 (Level Of Evidence 1B)