Facial Palsy

Original Editor - Wendy Walker.

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Redisha Jakibanjar, Muhammad Umar, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Ahmed Essam, 127.0.0.1, Naomi O'Reilly, Tarina van der Stockt and Darine Mohieldeen

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Facial palsy is caused by damage to the facial nerve (i.e. cranial nerve VII) that supplies the muscles of the face. It can be categorised into two types based on the location of the casual pathology:

- Central facial palsy

- Due to damage above the facial nucleus

- Peripheral facial palsy

- Due to damage at or below the facial nucleus[1]

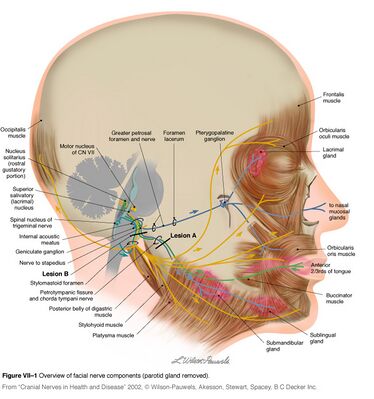

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

For more detail on the anatomy of the facial nerve, please see the Facial Nerve page.

The facial nerve has its nucleus in the pons. It takes a rather winding route before exiting the skull through the stylomastoid foramen. It then passes through the parotid gland, splitting into 5 branches:

- Temporal

- Zygomatic

- Buccal

- Mandibular

- Cervical

Please click here to see videos on the facial muscles.

Causes of Peripheral Facial Palsy[edit | edit source]

Upper motor neurone causes:[edit | edit source]

- Stroke

- Intracranial tumour

- Multiple sclerosis

- Syphilis

- HIV

- Vasculitides

- Haemorrhage [2]

Lower motor neurone causes[edit | edit source]

- Idiopathic or Bell's Palsy

This is the most common cause of facial paralysis. Its cause is not known,[3][4] but it is likely linked to Herpes Simplex infection.[5]

- Tumour

A tumour compressing the facial nerve can cause facial paralysis, but more commonly the facial nerve is damaged during surgical removal of a tumour. The most common tumour to cause facial palsy during surgical removal is the acoustic neuroma (also known as vestibular schwannoma).

Less common tumours to cause facial palsy (or the surgery to remove them) include cholesteatoma, hemangioma, facial schwannoma or parotid gland tumours.

- Infection

Ramsay Hunt syndrome - caused by Herpes Zoster infection. This is a syndromic occurrence of facial paralysis, herpetiform vesicular eruptions, and vestibulocochlear dysfunction. Patients presenting with Ramsay Hunt syndrome are generally at increased increased risk of hearing loss than patients with Bell's palsy, and the course of disease is frequently more painful. There is also a lower recovery rate from facial palsy in Ramsay Hunt syndrome patients[6][7]

Lyme disease - caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi via tick bites. Around 10 percent of patients affected with lyme disease develop facial paralysis - 25 percent of these patients present with bilateral facial palsy[8]

- Iatrogenic facial nerve damage

Occurs most commonly in temporomandibular joint replacement, mastoidectomy and parotidectomy[9]

Especially temporal and mastoid bone fractures[1]

- Congenital

A very small number of babies are born with congenital dysfunction of the facial nerve.

- Rare causes

These include:

- Neurosarcoidosis

- Otitis media

- Multiple sclerosis

- Moebius syndrome

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Millard-Gubler syndrome (AKA ventral pontine syndrome)

- An ipsilateral facial palsy with contralateral hemiplegia that involves the corticospinal tract and paralysis of lateral rectus on the ipsilateral side due to the involvement of the abducent nerve

- Foville Syndrome (AKA inferior medial pontine syndrome)

- An ipsilateral facial palsy, contralateral hemiplegia with ipsilateral conjugate gaze effects

- Eight-and-a-half syndrome

- Facial palsy with internuclear ophthalmoplegia and horizontal gaze palsy

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

- Diabetes[10]

- Pregnancy

- Potentially due to hypercoagulability, increased blood pressure and fluid load, viral infections and suppressed immunity[11]

- Ear infection

- Upper respiratory tract infection

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Paralysis of the muscles supplied by the facial nerve presents on the affected side of the face as follows:

Appearance and Range of Movement[edit | edit source]

- Inability to close the eye

- Inability to move the lips (e.g. into a smile, pucker)

- At rest, the affected side of the face may "droop"

- If, however, the person is in synkinesis, the affected side of the mouth may sit higher than the unaffected side. Facial synkinesis is defined as “abnormal facial movements that occur during volitional or spontaneous movement, for example, voluntary movement of the mouth may result in the closure of the eye”[12]

- Ectropion - i.e. the lower eyelid may droop and turn outward

Functional Effects[edit | edit source]

- Difficulty eating and drinking as the lack of lip seal makes it difficult to keep fluids and food in the oral cavity

- Reduced clarity of speech as the "labial consonants" (i.e. b, p, m, v, f) all require lip seal

- Dryness of the affected eye - more information on this is available here

Somatic Effects[edit | edit source]

The facial nerve supplies the lachrymal glands of the eye, the saliva glands, and to the muscle of the stirrup bone in the middle ear (the stapes). It also transmits taste from the anterior two thirds of the tongue.

Facial palsy often involves:

- Lack of tear production in the affected eye, causing a dry eye, and the risk of corneal ulceration

- There are two factors which contribute to dry eye in facial nerve palsy:

- The greater petrosal nerve, derived from the facial nerve, is affected - it supplies the parasympathetic autonomic component of the lacrimal gland, controlling the production of moisture / tearing in eyes

- The zygomatic branch of the facial nerve supplies orbicularis oculi, and the resulting paralysis leads to an inability (or reduced ability) to close the eye or blink. Thus, tears (or artificial lubrication in the form of drops, gel or ointment) are not spread across the cornea properly

- There are two factors which contribute to dry eye in facial nerve palsy:

- Hyperacusis - i.e. sensitivity to sudden loud noises

- Altered taste sensation

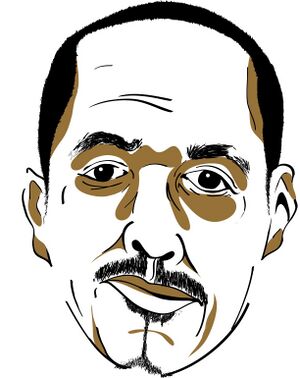

Appearance at rest of a flaccid facial palsy[edit | edit source]

In the early stages of peripheral facial palsy, whatever the cause, the following differences between the 2 sides of the face will often be apparent:

- Absence of horizontal lines on the forehead on the affected side

- Affected eye larger/more open than the unaffected one

- Lack of blink on the affected eye

- Altered position or absence of the naso-labial fold on the affected side

- Position of the affected corner of the mouth lower than the other side

The illustration here shows a left sided flaccid facial palsy:

Bell's Phenomenon[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Upper Motor Neuron versus Lower Motor Neuron[edit | edit source]

If the forehead is not affected (i.e. the patient is able to raise fully the eyebrow on the affected side) then the facial palsy is likely to be an upper motor neuron (UMN) lesion.[4] Paralysis which includes the forehead, such that the patient is unable to raise the affected eyebrow, is a lower motor neuron (LMN) lesion.

However, caution is advised in using preservation of forehead function to diagnose a central lesion. Patients may have sparing of forehead function with lesions in the pontine facial nerve nucleus, with selective lesions in the temporal bone, or with an injury to the nerve in its distribution in the face. It is worth remembering that a cortical lesion that produces a lower facial palsy / paresis is usually associated with a motor deficit of the tongue and weakness of the thumb, fingers, or hand on the ipsilateral side.[13]

Bell's Palsy versus Ramsey Hunt Syndrome[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Laboratory investigations include an audiogram, nerve conduction studies (ENoG), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography (EMG)[15][16]

- According to a 2013 clinical guideline by Baugh and colleagues, clinicians "should not obtain routine laboratory and imaging testing in patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy"[17][18]

Outcome Measures[19][edit | edit source]

- Sunnybrook facial grading system[20]

- Generally preferred by physiotherapists because of its sensitivity, and the section on synkinesis

- The result is expressed as a percentage (using the unaffected side of the face for comparison) so instinctively easy to understand

- The regions of the face are evaluated separately, with the use of five standard expressions:

- Eyebrow raise

- Eye closure

- Open mouth smile

- Lip pucker

- Snarl / show teeth

- House-Brackmann facial nerve grading scale

- Synkinesis assessment questionnaire

- Linear measurement index

- Facial disability index

- Lip-length (LL) and snout (S) indices

- Five-point scale

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Medical and surgical management depends on the cause of facial palsy.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The medical management of these conditions are discussed more in the linked pages, but Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome are treated with corticosteroids (prednisone), given within 72 hours of onset.[21][18][4] This can be accompanied by antiviral medication.[22][23][24]

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

As discussed in the linked pages, tumours such as acoustic neuromas and facial schwannomas are frequently resected surgically. Patients at high risk of a corneal ulcer may be offered oculoplastic surgery to protect the eye.

For patients with dense facial palsy and no nerve function, a number of surgical interventions may be used. These fall into the following categories:[25]

- Facial reanimation surgeries which involve nerve graft or anastomosis

- Facial reanimation surgeries which involve muscle transposition

- Static surgeries (i.e. plastic surgery) is used to improve symmetry at rest, but does not improve movement

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Early stages of Facial Palsy, onset to approx 5 months.

In the early stages of facial palsy, the most important thing to do is to check that patients are caring for their affected eye in an appropriate way. As the facial nerve is responsible for production of lubrication to the cornea, patients are highly likely to suffer from a dry eye in the early weeks and months of facial palsy. This puts them at risk of developing exposure keratitis/keratopathy AKA corneal ulcer, which can cause damage to vision in the affected eye[26]: management of the eye is crucial in preventing damage to the cornea and thus preventing loss of vision.

The therapist should educate the patient about dry eye management if this has not been done by other medical personnel. If the eye is looking red or the patient reports frequent episodes of redness, an urgent referral to opthalmology is required. Alternatively they should be advised to attend an eye hospital emergency department. For more information on dry eye including presentation, risk of corneal ulcer and management such as taping / use of artificial lubrication, please click here.

Other physiotherapy treatments include:

- Neuromuscular retraining (NMR) [27][28]

- For more information on this concept please see the Neuromuscular Reeducation in Facial Palsy page

- Electromyography (EMG) and mirror biofeedback[1][29]

- Trophic electrical stimulation (TES)[30]

- Proprioceptive neuro muscular facilitation (PNF) techniques[31]

- Kabat technique[32]

- Mime therapy[33]

- Includes treatments such as:[34]

- Self-massage

- Breathing and relaxation exercises

- Exercises to enhance coordination between both sides of the face and to reduce synkinesis

- Exercises to help with eye and lip closure

- Letter, word and facial expression exercises

- Includes treatments such as:[34]

Evidence for Physiotherapy Treatments[edit | edit source]

- According to clinical practice guidelines, physiotherapy is recommended ("weak recommendation") in Bell's palsy,[17][35] and neuromuscular re-education techniques have been found to be effective in increasing facial range of movement and symmetry, as well as reducing / minimising synkinesis[27][36][37][38][39]

- Mime therapy can improve functionality for patients with facial palsy

- The effect of electrical stimulation is controversial[1][40][41]

- One study found that PNF technique is more effective than conventional exercises[31]

- One study found PNF and the Kabat technique is more effective than no exercise[32]

Complications and Sequelae[edit | edit source]

Synkinesis (AKA aberrant regeneration) occurs after injury to the facial nerve. Synkinesis develops in cases of axonotmesis (i.e. damage to the facial nerve) and is, therefore, a normal sequelae to facial nerve damage.

Physiotherapy is extremely helpful in management of synkinesis, particularly neuromuscular retraining techniques and mirror feedback exercises; see the Synkinesis page for evidence.

Effects on Quality of Life[edit | edit source]

A large retrospective study of 920 patients from 2018 looked into the correlation between facial palsy severity and quality of life.[42] It concluded that: "A correlation between facial palsy severity and quality of life was found in a large cohort of patients comprising various etiologies. Additionally, novel factors that predict the quality of life in facial palsy were revealed".[42]

A 2011 study showed a group of 40 people photographs from people with facial palsy and also from people with no facial palsy, asking the viewers to rate the pictures in terms of attributing emotions to the person in the photo[43]. The results of this investigation were interesting: patients with facial palsy were consistently rated as having a "negative affect display" (ie. the viewers felt the photos showed negative emotions, such as sadness) the vast majority of the time. Indeed, patients with facial palsy are frequently all too aware that "I now look miserable even when I feel cheerful".

Resources[edit | edit source]

NHS information on Bell's Palsy

Facebook group for Facial Palsy UK

This link is to an introductory video about the effects of facial palsy

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Zhao Y, Feng G, Gao Z. Advances in diagnosis and non-surgical treatment of Bell's palsy. Journal of otology. 2015;10(1):7-12.

- ↑ Radiopedia Facial Palsy Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/facial-palsy (accessed 24.3.2022)

- ↑ Peitersen,E. Bell's Palsy; the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. Supplementum 2002;549:4-30.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Somasundara D, Sullivan F. Management of Bell's palsy. Australian prescriber.2017;40(3):94-7.

- ↑ Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell's Palsy. BMJ. 2004;329(7465):553-7.

- ↑ Hah YM, Kim SH, Jung J, Kim SS, Byun JY, Park MS et al. Prognostic value of the blink reflex test in Bell's palsy and Ramsay-Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(5):966-70.

- ↑ Cai Z1, Li H, Wang X, Niu X, Ni P, Zhang W et al. Prognostic factors of Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(2):e5898.

- ↑ Clark JR, Carlson RD, Sasaki CT, Pachner AR, Steere AC. Facial paralysis in Lyme disease. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(11):1341-5.

- ↑ Hohman MH, Bhama PK, Hadlock TA. Epidemiology of iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a decade of experience. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):260-5.

- ↑ Adour KK, Wingerd J, Doty HE. Prevalence of concurrent diabetes mellitus and idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy). Diabetes. 1975;24:449-51.

- ↑ Cohen Y, Lavie O, Granovsky-Grisaru S, Aboulafia Y, Diamant YZ. Bell palsy complicating pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55(3):184-8.

- ↑ van Landingham SW, Diels J, Lucarelli MJ. Physical therapy for facial nerve palsy: applications for the physician. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2018 Sep 1;29(5):469-75.

- ↑ Jenny AB, Saper CB. Organization of the facial nucleus and corticofacial projection in the monkey: a reconsideration of the upper motor neuron facial palsy. Neurology. 1987;37(6):930-9.

- ↑ MedEdPRO Facial Palsy Upper and Lower Motor Neuron Lesions - Dr MDM Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5T4G27xkckE

- ↑ Kumar A, Mafee MF, Mason T. Value of imaging in disorders of the facial nerve. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11(1):38-51.

- ↑ Zimmermann J, Jesse S, Kassubek J et al. Differential diagnosis of peripheral facial nerve palsy: a retrospective clinical, MRI and CSF-based study. J Neurol. 2019;266:2488–94.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, Schwartz SR, Drumheller CM, Burkholder R et al. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2013;149(3_suppl):S1-27.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kim SJ, Lee HY. Acute Peripheral Facial Palsy: Recent Guidelines and a Systematic Review of the Literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2020 Aug 3;35(30):e245. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e245. PMID: 32743989; PMCID: PMC7402921.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pereira LM, Obara K, Dias JM, Menacho MO, Lavado EL et al. Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2011;25(7):649-58.

- ↑ Jirawatnotai S, Jomkoh P, Voravitvet TY, Tirakotai W, Somboonsap N. Computerized Sunnybrook facial grading scale (SBface) application for facial paralysis evaluation. Arch Plast Surg. 2021;48(3):269-277.

- ↑ Gronseth GS, Paduga R. Evidence-based guideline update: Steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79 (22):2209-13.

- ↑ Butler DP, Grobbelaar AO. Facial palsy: what can the multidisciplinary team do? J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017; 10: 377-81.

- ↑ De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, Witterick IJ, Lin VY, Nedzelski JM, Chen JM. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2009;302(9):985-93.

- ↑ Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010(3).

- ↑ Mehta RP. Surgical treatment of facial paralysis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;2(1):1-5. doi:10.3342/ceo.2009.2.1.1

- ↑ Sohrab M, Abugo U, Grant M, Merbs S. Management of the eye in facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg. 2015 Apr;31(2):140-4. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1549292. Epub 2015 May 8. PMID: 25958900.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Manikandan N. Effect of facial neuromuscular re-education on facial symmetry in patients with Bell's palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(4):338-43.

- ↑ Van Swearingen JM, Brach JS. Changes in facial movement and synkinesis with facial neuromuscular reeducation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111:2370–2375.

- ↑ Bossi D, Buonocore M et al. Usefulness of BFB/EMG in facial palsy rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(14):809-15.

- ↑ Targan R S, Alon G, Kay SL. Effect of long-term electrical stimulation on motor recovery and improvement of clinical residuals in patients with unresolved facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 2000;122(2):246-52.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Tharani G, Rajalaxmi V, Yuvarani G, Kamatchi K. Comparison of PNF versus conventional exercises for facial symmetry and facial function in Bell's palsy. International Journal of Current Advanced Research. 2018;7(1):9347-50.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Monini S, Iacolucci CM, Di Traglia M, Lazzarino AI, Barbara M. Role of Kabat rehabilitation in facial nerve palsy: a randomised study on severe cases of Bell's palsy. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2016;36(4):282.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Beurskens CH, Heymans PG. Mime therapy improves facial symmetry in people with long-term facial nerve paresis: a randomised controlled trial. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006;52(3):177-83.

- ↑ Beurskens CH, Devriese PP, Van Heiningen I, Oostendorp RA. The use of mime therapy as a rehabilitation method for patients with facial nerve paresis. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2004;11(5):206-10.

- ↑ de Almeida JR, Guyatt GH, Sud S, Dorion J, Hill MD, Kolber MR et al. Management of Bell palsy: clinical practice guideline. Cmaj. 2014;186(12):917-22.

- ↑ Brach JS, Van Swearingen JM. Physical therapy for facial paralysis: a tailored treatment approach. Phys Ther. 1999;79:397-404.

- ↑ van Landingham SW, Diels J, Lucarelli MJ. Physical therapy for facial nerve palsy. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2018;29(5):469-75.

- ↑ Karp E, Waselchuk E, Landis C, Fahnhorst J, Lindgren B, Lyford-Pike S. Facial rehabilitation as noninvasive treatment for chronic facial nerve paralysis. Otology & Neurotology. 2019;40(2):241-5.

- ↑ 1. Khan AJ, Szczepura A, Palmer S, et al. Physical therapy for facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy): An updated and extended systematic review of the evidence for facial exercise therapy. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2022;36(11):1424-1449. doi:10.1177/02692155221110727

- ↑ Puls WC, Jarvis JC, Ruck A, Lehmann T, Guntinas-Lichius O, Volk GF. Surface electrical stimulation for facial paralysis is not harmful. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(3):347-53.

- ↑ Teixeira LJ, Valbuza JS, Prado GF. Physical therapy for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011(12).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Tavares-Brito J, van Veen MM, Dusseldorp JR, Bahmad F Jr, Hadlock TA. Facial palsy-specific quality of life in 920 patients: correlation with clinician-graded severity and predicting factors. Laryngoscope. 2018.

- ↑ Ishii LE, Godoy A, Encarnacion CO, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, Ishii M. What faces reveal: impaired affect display in facial paralysis. Laryngoscope. 2011 Jun;121(6):1138-43. doi: 10.1002/lary.21764. Epub 2011 May 9. PMID: 21557237.