Bell's Palsy

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors = Wendy Walker, Lilian Ashraf, Kim Jackson, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Lucinda hampton, Khloud Shreif, Rishika Babburu, Redisha Jakibanjar, Claire Knott, Shwe Shwe U Marma, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

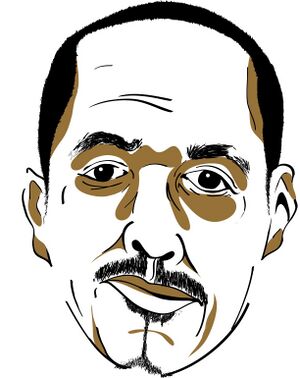

Bell's Palsy, or Bell Palsy, is facial paralysis which is caused by dysfunction of Cranial Nerve VII, the Facial Nerve.

Also known as Idiopathic Peripheral Facial Palsy, it is named after Sir Charles Bell [1774 to 1842], who was a Scottish surgeon, neurologist and anatomist.

It results in inability or reduced ability, to move the muscles on the affected side of the face ie. Facial Palsy.

Bell's Palsy is an idiopathic condition, i.e. no specific cause has been conclusively established. It is a diagnosis of exclusion: once other causes of facial palsy have been eliminated, the patient is said to have Bell's Palsy[1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Population studies show an average incidence of 11 to 40 cases per 100,00 population[2][3].

It is the most common cause of acute unilateral facial paralysis, thought to cause between 60 and 75% of all unilateral facial palsy cases[1].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

The facial nerve is damaged by inflammation within the nerve causing it to become enlarged[3], at the point where the nerve exits the skull through the stylomastoid foramen.

Ischemia occurs as the nerve swells in its bony canal, blocking neural blood supply.

Having said that Bell's Palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion and that we are not certain what causes the nerve inflammation[4], there is evidence to suggest that in the majority of cases it is likely to be linked to Herpes Simplex infection[5][6].

For more information on the course of Cranial Nerve VII, please see the Facial Nerve page.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Loss of control of the muscles on one side of the face is the main physical presentation.

Some patients also report general malaise in the first few days of onset, as well as some pain in the region of the ipsilateral mastoid (known as otalgia), but many patients have no otalgia or malaise.

At onset, the paralysis may be complete, or partial (paresis) and although it frequently affects all branches of the facial nerve on the affected side, resulting in loss of control of that side of the mouth and the ipsilateral eye, in a few cases only one or two branches of the facial nerve are affected.

For a more detailed description of the clinical presentation, please see the Facial Palsy page.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Bell's Palsy is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, so once other causes of facial palsy have been eliminated, we call an isolated facial palsy Bell's Palsy, or Idiopathic Facial Palsy[1][7][8].

MRI scanning can be used to exclude other causes of facial nerve dysfunction[9], such as Facial Schwannoma or Acoustic Neuroma.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Corticosteroid medication is generally considered to be the 1st line treatment for Bell's Palsy, providing the best results when treatment starts within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms[1][11][3]. There are a number of studies showing benefit for steroids given within this time-frame[12][13][14][15].

Although some patients are also prescribed antivirals, many studies do not demonstrate any advantage of using antiviral medication combined with corticosteroids over corticosteroids alone.

- In 2012 the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology published a review Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy, looking specifically at studies published since 2000. This consisted of 9 studies, 2 of which were rated Class 1 (high methodological quality).

The conclusions & recommendations were: For patients with new-onset Bell's palsy, steroids are highly likely to be effective and should be offered to increase the probability of recovery of facial nerve function [this conclusion was based on 2 Class 1 studies, Level A, & the risk difference was 12.8%-15%]. They concluded that for new-onset Bell's Palsy, antiviral agents in combination with steroids do not increase the probability of facial functional recovery by >7%, but "because of the possibility of a modest increase in recovery, patients might be offered antivirals (in addition to steroids" [Level C evidence]. They also remark "patients offered antivirals should be counselled that a benefit from antivirals has not been established, and, if there is a benefit, it is likely that it is modest at best".

- The Cochrane review "Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy"[16] Idiopathic facial paralysis concludes:"Moderate-quality evidence from randomised controlled trials showed no additional benefit from the combination of antivirals with corticosteroids compared to corticosteroids alone for the treatment of Bell's palsy of various degrees of severity. Moderate-quality evidence showed a small but just significant benefit of combination therapy compared with corticosteroids alone in severe Bell's palsy."

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Approximately 70% of patients who have Bell's Palsy will have complete recovery within approximately 8 weeks.[18][19][20]

The remaining 30% will suffer long term sequelae ranging from mild to severe, which can include facial weakness, synkinesis, involuntary movements, and persistent lachrymation.[1][21][22]

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

For physiotherapy interventions please see Facial Palsy page.

It is also important to provide information on care of the eye in order to prevent formation of corneal ulcer: see advice page on Dry Eye. Referral to an opthalmologist should be considered.

A number of people with Bell's Palsy suffer from Xerostomia, or Dry Mouth. This occurs because two of the three main salivary glands receive their parasympathetic nerve supply from the facial nerve: the sublingual and glossopharyngeal glands. (The parotid gland is not innervated by the facial nerve, so is unaffected.) See the advice page on Dry Mouth.

Bell's Palsy patients with long term facial paralysis may also start to experience dental problems: see advice page on Dental Issues in Facial Palsy.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following conditions also result in facial palsy:

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome - caused by Herpes Zoster infection (AKA Shingles)[9][9], generally the patient will have vesicles and involvement of other cranial nerves

- Acoustic Neuroma - MRI scan should be used to exclude this[9]

- Facial Schwannoma - caused by a tumour of the facial nerve; MRI scanning (with contrast) will show this

- Neurological (consider Multiple Sclerosis, and Guillain-Barre Syndrome )

- Infections[9], such as acute otitis media, Lyme Disease, cholesteatoma, viral infections including Epstein-Barr Virus

- Neoplasm, particularly parotid malignancy, but also a number of brain tumours can (rarely) cause facial palsy, including meningioma

- Upper Motor Neurone [UMN] facial palsy, generally caused by Stroke - note, in many UMN causes the forehead does not suffer from paralysis

Resources[edit | edit source]

The charity Facial Palsy UK has a page on Bell's Palsy.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Eviston TJ, Croxson GR, Kennedy PGE, et al Bell's palsy: aetiology, clinical features and multidisciplinary care Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2015;86:1356-1361

- ↑ Katusic SK; Beard CM; Wiederholt WC; Bergstralh EJ; Kurland LT Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell's palsy, Rochester, Minnesota, 1968-1982. Ann Neurol. 1986; 20(5):622-7

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Somasundara, D., & Sullivan, F. (2017). Management of Bell's palsy. Australian prescriber, 40(3), 94–97. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2017.030

- ↑ Peitersen,E. Bell's Palsy; the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. Supplementum 2002;549:4-30

- ↑ Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell's Palsy. BMJ 2004; 329(7465):553-7

- ↑ Murakami, S. et al. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann. Intern. Med. 124, 27–30 (1996).

- ↑ Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405

- ↑ Zhao H, Zhang X, Tang Y, Zhu J, Wang X, Li S: Bell's Palsy: Clinical Analysis of 372 Cases and Review of Related Literature. Eur Neurol 2017;77:168-172. doi: 10.1159/000455073

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Zimmermann, J., Jesse, S., Kassubek, J. et al. Differential diagnosis of peripheral facial nerve palsy: a retrospective clinical, MRI and CSF-based study. J Neurol 266, 2488–2494 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09387-w

- ↑ Osmosis. Bell's Palsy - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ic1hKbk4CKc[last accessed 23/4/2020]

- ↑ Hato N, Murakami S, Gyo K. Steroid and antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy. Lancet 2008; 371: 1818–20

- ↑ Engstrom M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Axelsson S, Pitkaranta A, Hultcrantz M, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;(11):993-1000

- ↑ Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1598-607

- ↑ Axelsson S, Berg T, Jonsson L, Engström M, Kanerva M, Stjernquist-Desatnik A. Bell's palsy - the effect of prednisolone and/or valaciclovir versus placebo in relation to baseline severity in a randomised controlled trial. Clin Otolaryngol. 2012;37(4):283-90

- ↑ Berg T, Bylund N, Marsk E, Jonsson L, Kanerva M, Hultcrantz M, et al. The effect of prednisolone on sequelae in Bell's palsy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012; 138(5):445-9

- ↑ Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD001869.

- ↑ FacialPalsyUK. What is the treatment for Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vIVCg6lHFcg [last accessed 23/4/2020]

- ↑ Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;(549):4-30. PMID: 12482166.[1]

- ↑ Morgenlander JC, Massey EW. Bell's Palsy. Ensuring the best possible outcome. Postgraduate Medicine 1990;88(5):157‐61, 164.

- ↑ Baugh, R.F., Basura, G.J., Ishii, L.E., et al. (2013) Clinical practice guideline: Bell's palsy. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 149(3 Suppl), S1-S27

- ↑ Schirm J, Mulkens PS. Bell's palsy and herpes simplex virus. APMIS. 1997 Nov; 105(11):815-23

- ↑ Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: Steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell's palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 Apr 10; 56(7):830-6.