Ramsay Hunt Syndrome

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Poonam Sepat, Kim Jackson, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Naomi O'Reilly and Wendy Snyders

Introduction[edit | edit source]

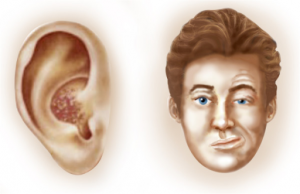

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome [RHS] is a peripheral facial palsy or cranial nerve (CN) VII and is caused by reactivation of of latent Varicella Zoster virus[1]. It is generally accompanied by herpes blisters in the neck and head areas, often in the ear and mouth acvity[1] however, occasionally there will be no rash visible. All the communicating nerves (cervical nerves C2, C3, and C4) and CNs V, VIII, IX, and X) can also be involved but cases of polyneuropathy including the many communicating nerves are rare[1]. About 12% of peripheral facial palsy cases are associated with RHS[2].

The syndrome is named after Dr J. Ramsey Hunt, the physician who first described the syndrome at a meeting of the American Neurological Association in 1906. He subsequently published his article on the subject in 2007[3].

When compared with Bell's Palsy, RHS has a higher incidence of incomplete recovery with longstanding sequelae[4][5].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

RHS is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) within the dorsal ganglion of the Facial Nerve, the 7th Cranial Nerve. As the 8th cranial nerve, known as the auditory nerve or the vestibulocochlear nerve, lies next to the sensory ganglion of the facial nerve within the facial canal, both nerves are usually involved[6].

Risk factors for the reactivation VZV include upper respiratory infections, smoking, diabetes, emotional stress, immunosuppresive therapy, cancer and chronic renal failure[2].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most common characteristics are acute facial palsy, otalgia (ear ache) and red vesicular rashes in the external auditory canal and pinna[2]. The otalgia may occur at the same time as the facial palsy, or the palsy may occur a few days after the onset of earaches. Other symptoms such as nystagmus, nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, hearing loss (sensorineural), vertigo and temporal headaches can also be present[2].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

RHS diagnosis is largely based on history, clinical findings, and neurological examination[7].Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and MRI (brain) has limited diagnostic value[7].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following conditions can present in with similar symptoms:

- Bell's Palsy - this is the most common cause of sudden onset, non-traumatic facial palsy, and can be differentiated from RHS by the absence of severe otalgia (only mild pain in the region of the mastoid usually occurs in Bell's Palsy) and the absence of vesicles and involvement of other cranial nerves.

- Postherpetic Neuralgia - not associated with facial palsy

- Acoustic Neuroma - MRI scan should be used to exclude this

- Temporomandibular Disorders - not associated with facial palsy

- Trigeminal Neuralgia - not associated with facial palsy

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Corticosteroids and antiviral medication are the 1st line treatment for RHS, providing the best results when treatment starts within 72 hours of t of symptoms[8][9][10]. Over 80% of patients who start antiviral medication within 72 hours have good recovery[1]. Antiviral agents such as acyclovir reduce acute pain, improve the herpes zoster lesions and prevent postherpetic neuralgia[7].

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy management of the facial paralysis or weakness is as detailed in the section on Facial Palsy.

It is also important to provide information on care of the eye in order to prevent the formation of corneal ulcer: see advice page on Dry Eye. Referral to an opthalmologist should be considered.

RHS patients with long term facial palsy may also start to experience dental problems: see advice page on Dental Issues in Facial Palsy.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kanerva M, Jones S, Pitkaranta A. Ramsay Hunt syndrome: characteristics and patient self-assessed long-term facial palsy outcome. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2020 Apr;277(4):1235-45.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Psillas G, Dova S, Ieridou F, Kyrgidis A, Constantinidis J. Ramsay Hunt syndrome: clinical presentation and prognostic factors. B-ENT. 2019 Jan 1;15(4):297-302.

- ↑ J. Ramsay Hunt, On Herpetic Inflammations of the Geniculate Ganglion. A New Syndrome and its Complications. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, February 1907, Volume 34, Issue 2, pp 73-96

- ↑ Cai Z1, Li H, Wang X, Niu X, Ni P, Zhang W, Shao B. Prognostic factors of Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jan;96(2):e5898.

- ↑ Hah YM, Kim SH, Jung J, Kim SS, Byun JY, Park MS, Yeo SG. Prognostic value of the blink reflex test in Bell's palsy and Ramsay-Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018 Oct;45(5):966-970. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2018.01.007. Epub 2018 Feb 3.

- ↑ C J Sweeney, D H Gilden. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:149-154

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Jeon Y, Lee H. Ramsay hunt syndrome. Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2018 Dec 1;18(6):333-7.

- ↑ Hato N, Murakami S, Gyo K. Steroid and antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy. Lancet 2008; 371: 1818–20

- ↑ Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, Honda N, Gyo K, Yanagihara N. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol 1997; 41: 353–7.

- ↑ Daniel P Butler and Adriaan O Grobbelaar. Facial palsy: what can the multidisciplinary team do? J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017; 10: 377–381. Published online 2017 Sep 25. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S125574