Trigeminal Neuralgia

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Abbey Wright, Admin, Scott Buxton, Joao Costa, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Claire Knott, Laura Ritchie, Naomi O'Reilly and Vanessa Rhule

Introduction[edit | edit source]

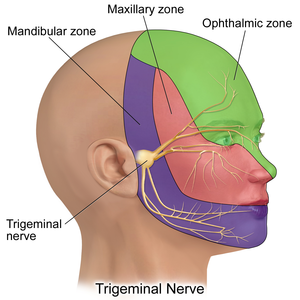

Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN) is a facial pain syndrome. It is typically characterised by short term, unilateral facial pain following the sensory distribution of cranial nerve V, the Trigeminal Nerve. Most commonly the pain radiates to the mandibular or maxillary regions. In some cases, it is accompanied by a brief facial spasm or tic.[1] Trigeminal neuralgia also called tic douloureux; transports sensation from the face to the brain.[2] It's an intermittent pain of high intensity that is raised by light touch.[3]

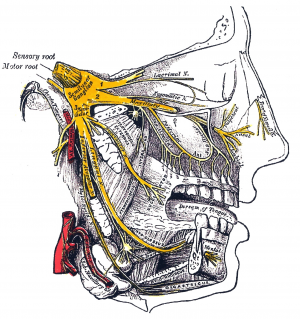

The Trigeminal nerve, the fifth cranial nerve, is the nerve responsible for sensation in the face, and control of motor functions such as biting and chewing.

"Trigeminal" = tri, and "-geminus" or twin, or thrice twinned derives from the fact that it has three major branches:

- Ophthalmic nerve (V1) 1st branch - sensory

- Maxillary nerve (V2) 2nd branch - sensory

- Mandibular nerve (V3) 3rd branch - sensory and motor. Controlling the muscles of mastication: Temporalis and Masseter.

Other Names of TN[edit | edit source]

Trigeminal Neuralgia is also known by the following names:[4]

- Tic Douloureux

- Prosopalgia

- Fothergill's Disease

- Suicide Disease

Aetiology/ Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

The exact aetiology of TN has not been clearly explained.[5] The compression of the trigeminal nerve root, either at the dorsal root entry or by a blood vessel is one of the biggest causes or contributing factors.[6] Symptoms of pain are usually caused by compression of the Trigeminal nerve route in 80-90% of cases.[1] Which is located within the Central Nervous System. The ignition theory or hypothesis suggests that TN is a consequence of abnormalities in the afferent neurones of the trigeminal root or ganglion.[7] Any damage to the axons makes them hyperexcitable and therefore generates this chronic and progressive painful condition.[5] Furthermore, the episodes of pain go beyond the original point of stimulus and regulate themselves their duration.[8]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Trigeminal Neuralgia is first of all due to the demyelinating disorder.[9][10] Common causes of compression can be tumours or their associated blood vessels however in many cases the cause can be unknown.[1]

Other causes may include:

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): approximately 1-2% of patients with MS develop TN.[11][12]

- A tumor

- Physical damage to the nerve

- Family history of blood vessel formation[13]

- Craniovertebral junction abnormalities such as Chiari Malformations

- Bony disorders like Paget's disease

- Osteogenesis imperfecta[14]

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

The pain in TN is usually localized in one side of the face and is felt in contact of a light touch or a sound. It's usually triggered by the following activities:[15]

- brushing teeth

- shaving

- rubbing

- touching the painful area of the face

- putting on makeup

- eating or drinking

- speaking

- being exposed to the wind

- pain in the cheek, jaw, teeth, gums, and lips

- pain in one side of the face

- tingling or numbness in the face before starting to feel pain[13]

Studies suggest that trigger zones, or areas of increased sensitivity, are present in one half of patients and often lie near the nose or mouth

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Recent estimates suggest the prevalence is approximately 4.5 cases per 100,000 population, with an incidence of approximately 15,000 cases per year.[16]

The worldwide prevalence ranges between 10 and 300/100 000. [5] In 90% of patients, the disease begins after age 40 years, generally between 60-70 years. Women are more affected than men.[17]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

TN presents as a sharp, stabbing unilateral facial pain that is normally episodic in nature. [18]

Area of pain[edit | edit source]

60% of patients with TN present with lancinating pain shooting from the corner of the mouth to the angle of the jaw

30% experience jolts of pain from the upper lip or canine teeth to the eye and eyebrow, sparing the orbit itself—

this distribution falls between the division of the first and second portions of the nerve.

According to Patten[19], fewer than 5% of patients experience ophthalmic branch involvement.

Characteristic Descriptors of pain[edit | edit source]

The pain quality is severe, paroxysmal, and lancinating.

It usually starts with a sensation of electrical shocks, then quickly increases in less than 20 seconds to an excruciating pain felt deep in the face, often contorting the patient's expression. The pain then begins to fade within seconds, only to give way to a burning ache lasting seconds to minutes. During attacks, patients may grimace, wince, or make an aversive head movement, as if trying to escape the pain, thus producing an obvious movement or tic; hence the term "tic douloureux."

Frequency of pain[edit | edit source]

The number of attacks may vary from less than 1 per day to hundreds per day.

Outbursts fully abate between attacks, even when they are severe and frequent.

Diagnosis and Classification[edit | edit source]

The International Headache Society (IHS) has published strict criteria[20] for TN:

A - Paroxysmal attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes, affecting 1 or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve and fulfilling criteria B and C

B - Pain has at least 1 of the following characteristics: (1) intense, sharp, superficial or stabbing; or (2) precipitated from trigger areas or by trigger factors

C - Attacks stereotyped in the individual patient

D - No clinically evident neurologic deficit

E - Not attributed to another disorder

No laboratory, electrophysiologic, or radiologic testing is routinely indicated for the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia (TN), as patients with characteristic history and normal neurologic examination may be treated without further investigation.

The diagnosis of TN is almost entirely based on the patient's history and in most cases no specific laboratory tests are needed.

MRI scanning is often indicated simply to exclude other causes of the pain, such as pressure on the trigeminal nerve from Acoustic Neuroma.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

- McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

- Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

- Brief Pain Inventory - Facial (BPI-F)

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

A range of anti-epileptic drugs has proved to be useful in the management of TN, with carbamazepine in particular having a large number of studies demonstrating efficacy[21]. Non anti-epileptic drugs can also be prescribed, often in conjunction with carbamazepine[22].[23]

Other medications include muscle relaxants and tricyclic antidepressants.[15]

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Studies suggest that approximately 25% of TN patients go on to require surgery as their condition worsens over years, and drug management becomes less effective[24]. Microvascular decompression and radiofrequency thermorhizotomy are the most common surgical procedures employed in these cases.

The other common surgical procedures include:

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery

- Gamma-knife Radiosurgery

- Glycerol injections

- Radiofrequency Thermal Lesioning[15]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy promotes, maintains, and restores the physical, psychological, and social wellbeing of an individual by the use of different techniques.[25] The physiotherapy treatment of TN focusses on the patient's goals and needs.

According to Reeta et.al in their study done in 2016[26], the physiotherapy treatment of TN patients is efficient and includes:

- Electrical Stimulation (TENS) as the most effective and most often used technique

- Interferential Therapy (IFT)

- Ultrasound

Physiotherapy Management will also aim at reducing pain and improve the ability to carry on with the activities of daily living (ADLs) by using:[27]

- Acupuncture to relieve facial pain and pressure

- Isometric neck exercises

- Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises

- Cardiovascular exercises to improve health and fitness levels

- Functional Activities for problems associated with ADLs

- Patient's education on diet, management of sleep, and rest

- Advice on how to avoid using cold water for drinking and washing their face but also chewing with the non affected side.

Physiotherapy can alternatively play different roles in the management of TN in educating, advising, and motivating patients. [28] Although physiotherapy treatment is effective in the Management of TN, there is a need for awareness of its role among the general public.[26]

Complementary Approaches[edit | edit source]

People with TN have been using some useful complementary approaches along with the medical treatment to medical management usually used to relieve pain and improve their health.[29] These techniques include:

- Low-impact yoga

- Aromatherapy

- Meditation

- Acupuncture

- Upper Cervical Chiropractic

- Vitamin Therapy

- Nutritional Therapy

- Injections of botulinum toxin

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The main differential diagnoses for TN are:

- Atypical facial pain - this common facial pain is less intense than TN, described as a dull or throbbing ache which lasts for minutes to hours

TN should also be differentiated from other causes of orofacial pain and headaches such as:[5]

- Headache disorders such as Migraine and Cluster headaches

- Dental pain

- Temporo-mandibular Joint disorders

- Other neuralgias

- Tumor

- Sinusitis

- Postherpetic neuralgia

Risks Factors[edit | edit source]

According to [5], the following have been identified as important risk factors for TN:

- Increased age

- Stroke

- Hypertension in women

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

- Tumors in the trigeminal nerve region

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. Bmj. 2014 Feb 17;348:g474

- ↑ What is Trigeminal Neuralgia? Available from:https://fpa-support.org/learn/ (accessed 29 September, 2020)

- ↑ Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. Bmj. 2014 Feb 17;348:g474

- ↑ Trigeminal Neuralgia. Available from: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/neurosurgery/services/conditions/trigeminal-neuralgia.aspx ( Accessed 2 September 2020)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Vasappa CK, Kapur S, Krovvidi H. Trigeminal neuralgia. Bja Education. 2016 Oct 1;16(10):353-6.

- ↑ Zhang J, Yang M, Zhou M, He L, Chen N, Zakrzewska JM. Non‐antiepileptic drugs for trigeminal neuralgia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(12).

- ↑ Devor M, Amir R, Rappaport ZH. Pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia: the ignition hypothesis. The Clinical journal of pain. 2002 Jan 1;18(1):4-13.

- ↑ Taltia AA. Trigeminal neuralgia. International Journal of Orofacial Biology. 2017 Jul 1;1(2):48.

- ↑ Burchiel KJ. Abnormal impulse generation in focally demyelinated trigeminal roots. Journal of neurosurgery. 1980;53(5):674-83.

- ↑ Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 2001 Dec 1;124(12):2347-60.

- ↑ Rushton JG, Olafson RA. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclerosis: report of 35 cases. Archives of neurology. 1965;13(4):383-6.

- ↑ Jensen TS, Rasmussen P, Reske‐Nielsen E. Association of trigeminal neuralgia with multiple sclerosis: clinical and pathological features. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1982;65(3):182-9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 What to know about Trigeminal neuralgia? Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/160252#causes ( Accessed 30 September 2020)

- ↑ Duransoy YK, Mete M, Akçay E, Selçuki M. Differences in individual susceptibility affect the development of trigeminal neuralgia. Neural regeneration research. 2013 May 15;8(14):1337

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Trigeminal Neuralgia. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/trigeminal-neuralgia#symptoms (Accessed 29 September 2020)

- ↑ Katusic S, Williams DB, Beard M, Bergstralh EJ, Kurland LT. Epidemiology and clinical features of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia: similarities and differences, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Neuroepidemiology. 1991;10(5-6):276-81.

- ↑ Manzoni GC, Torelli P. Epidemiology of typical and atypical craniofacial neuralgias. Neurological Sciences. 2005 May 1;26(2):s65-7.

- ↑ Eller JL, Raslan AM, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia: definition and classification. Neurosurgical focus. 2005 May 1;18(5):1-3.

- ↑ Patten J. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Neurological Differential Diagnosis. 2nd ed. London: Springer;1996:373-5.

- ↑ The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 Suppl 1:9-160

- ↑ Rockliff BW, Davis EH. Controlled sequential trials of carbamazepine in trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol.1966;15(2):129-36

- ↑ He L, Wu B, Zhou M. Non-antiepileptic drugs for trigeminal neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004029

- ↑ Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, Argoff C, Brainin M, Burchiel K, et al. AAN‐EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. European journal of neurology. 2008;15(10):1013-28.

- ↑ Dalessio DJ. Trigeminal neuralgia. A practical approach to treatment. Drugs.1982;24(3):248-55

- ↑ Physiotherapy/Physical Therapy. Available from: Physiotherapy / Physical Therapy( Accessed 2nd October, 2020)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Reeta, Kumar U, Kumar V, Alam M, Islami D, Lal W et al. A Survey to Observe the Commonly Used Treatment Protocol for Trigeminal Neuralgia by Physiotherapist. International Journal of Physiotherapy. 2016;3(5):643-646

- ↑ Trigeminal neuralgia. Available from: https://www.physio.co.uk/what-we-treat/chronic-pain-fatigue/trigeminal-neuralgia.php (Accessed on 2nd October, 2020)

- ↑ Khanal D, Khatri SM, Anap D. Is there Any Role of Physiotherapy in Fothergill's Disease?. Journal of Yoga & Physical Therapy. 2014 Apr 1;4(2):1.

- ↑ Trigeminal Neuralgia Fact Sheet. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/patient-caregiver-education/fact-sheets/trigeminal-neuralgia-fact-sheet (Accessed 30 September 2020)

- ↑ John Hopkins Medicine. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Frequently Asked Questions. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDaMsJz8Rp4 [last accessed 03/10/2020]