Quadriceps Muscle Strain: Difference between revisions

Rucha Gadgil (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

== Mechanism of injury: == | == Mechanism of injury: == | ||

There are generally three mechanisms for quadriceps strain. <br>1. Sudden deceleration of the leg (e.g. kicking), <br>2. violent contraction of the quadriceps (sprinting) and <br>3. rapid deceleration of an overstretched muscle (by quickly change of direction). | There are generally three mechanisms for quadriceps strain. <br>1. Sudden deceleration of the leg (e.g. kicking), <br>2. violent contraction of the quadriceps (sprinting) and <br>3. rapid deceleration of an overstretched muscle (by quickly change of direction). | ||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

| Line 202: | Line 202: | ||

== References<br> == | == References<br> == | ||

<br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br>(24) Hurley, Michael V., Joanne Rees, and Di J. Newham. "Quadriceps function, proprioceptive acuity and functional performance in healthy young, middle-aged and elderly subjects." Age and ageing 27.1 (1998): 55-62. (Level 3A)<br>(25) Marks, M. C., and H. G. Chambers. "Clinical utility of the Duncan‐Ely test for rectus femoris dysfunction during the swing phase of gait." Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 45.11 (2003): 763-768. (Level 1A)<br>(26) Kalimo H, Rantanen J, Järvinen M. Muscle injuries in sports. Baillieres Clin Orthop. 1997;2: 1-24 (Level 2C)<br>(27) Hamilton, Bruce. "Hamstring muscle strain injuries: what can we learn from history?." British journal of sports medicine 46.13 (2012): 900-903. (Level 5)<br>(28) The early management of muscle strains in the elite athlete: best practice in a world with a limited evidence basis. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:158–9. (Level 1B)<br>(29) Natsis, Konstantinos, et al. "Bilateral rectus femoris intramuscular haematoma following simultaneous quadriceps strain in an athlete: a case report." Journal of medical case reports 4.1 (2010): 56. (level 4 : case report (series)<br>(30) Taylor, Clare, Rathan Yarlagadda, and Jonathan Keenan. "Repair of rectus femoris rupture with LARS ligament." BMJ case reports 2012 (2012): bcr0620114359. (level 4: case series)<br>(31) (Machotka, Zuzana, et al. "Anterior cruciate ligament repair with LARS (ligament advanced reinforcement system): a systematic review." Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology 2.1 (2010): 1.) (level 1A) | |||

[[Category:Injury]] [[Category:Knee_Injuries]] [[Category:Knee]] [[Category:Muscles]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category:Sports_Injuries]] | [[Category:Injury]] [[Category:Knee_Injuries]] [[Category:Knee]] [[Category:Muscles]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category:Sports_Injuries]] | ||

Revision as of 08:12, 25 July 2018

Original Editors - Maxime Tuerlinckx

Top Contributors - Mandeepa Kumawat, Maxime Tuerlinckx, Carlos Areia, Lucinda hampton, Shanna Blyckaerts, Admin, Shaimaa Eldib, Wanda van Niekerk, Jelle Van Hemelryck, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Frederik Töpke, Joao Costa, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1, Rucha Gadgil, Evan Thomas, Scott Buxton, Naomi O'Reilly, Daphne Jackson and Fasuba Ayobami

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

A quadriceps muscle strain is an acute tearing injury of the quadriceps. This injury is usually due to an acute stretch of the muscle often at the same time of a forceful contraction or repetitive functional overloading. The quadriceps which consists of four parts, can be overloaded by repeated eccentric muscle contractions of the knee extensor mechanism. [1]

Acute strain injuries of the quadriceps commonly occur in athletic competitions such as soccer, rugby, and football. These sports regularly require sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the quadriceps during regulation of knee flexion and hip extension. Higher forces across the muscle–tendon units with eccentric contraction can lead to strain injury. Excessive passive stretching or activation of a maximally stretched muscle can also cause strains. Of the quadriceps muscles, the rectus femoris is most frequently strained. Several factors predispose this muscle and others to more frequent strain injury. These include muscles crossing two joints, those with a high percentage of Type II fibers, and muscles with complex musculotendinous architecture. Muscle fatigue has also been shown to play a role in acute muscle injury.[1]

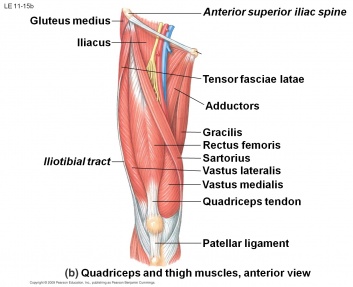

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Quadriceps femoris is a hip flexor and a knee extensor. It is located in the anterior compartment of the thigh. This muscle is composed of 4 sub components:

The Rectus femoris is the only part of the muscle participating in both flexion of the hip and extension of the knee. The other 3 parts are only involved in the extension of the knee. The rectus femoris is the most superficial part of the quadriceps and it crosses both the hip and knee joints. So it is more susceptible to stretch-induced strain injuries. [2] The most common sites of strains are the muscle tendon junction just above the knee (both distal and proximal but most frequently at the distal muscle-tendon) and in the muscle itself.

Epidemiology/ Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are 4 types of skeletal muscle injuries: muscle strain, muscle contusion, muscle cramp and muscle soreness.

Literature study does not reveal great consensus when it comes to classifying muscle injuries, despite their clinical importance. However, the most differentiating factor is the trauma mechanism. Muscle injuries can therefore be broadly classified as either traumatic (acute) or overuse (chronic) injuries.

Acute injuries are usually the result of a single traumatic event and cause a macro-trauma to the muscle. There is an obvious link between the cause and noticeable symptoms. They mostly occur in contact sports such as rugby, soccer and basketball because of their dynamic and high collision nature.[3][4]

Overuse, chronic or exercise-induced injuries are subtler and usually occur over a longer period of time. They result from repetitive micro-trauma to the muscle. Diagnosing is more challenging since there is a less obvious link between the cause of the injury and the symptoms.[3]

Mechanism of injury:[edit | edit source]

There are generally three mechanisms for quadriceps strain.

1. Sudden deceleration of the leg (e.g. kicking),

2. violent contraction of the quadriceps (sprinting) and

3. rapid deceleration of an overstretched muscle (by quickly change of direction).

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Grades of quadriceps strain :[edit | edit source]

Strains are graded 1 to 3 depending on how bad the injury is with a grade 1 being mild and a grade 3 involving a complete or near complete tear of the muscle.

Grade 1 symptoms

Symptoms of a grade 1 quadriceps strain are not always serious enough to stop training at the time of injury. A twinge may be felt in the thigh and a general feeling of tightness. The athlete may feel mild discomfort on walking and running might be difficult. There is unlikely to be swelling. A lump or area of spasm at the site of injury may be felt.

Grade 2 symptoms

The athlete may feel a sudden sharp pain when running, jumping or kicking and be unable to play on. Pain will make walking difficult and swelling or mild bruising would be noticed. The pain would be felt when pressing in on the suspected location of the quad muscle tear. Straightening the knee against resistance is likely to cause pain and the injured athlete will be unable to fully bend the knee.

Grade 3 symptoms

Symptoms consist of a severe, sudden pain in the front of the thigh. The patient will be unable to walk without the aid of crutches. Bad swelling will appear immediately and significant bruising within 24 hours. A static muscle contraction will be painful and is likely to produce a bulge in the muscle. The patient can expect to be out of competition for 6 to 12 weeks.[5]

Observation and palpation[edit | edit source]

The therapist will have a close look at the injured area, observing for swelling and bruising in particular. They should also observe the patient in standing and walking, looking for postural abnormalities.Palpation of the quadriceps muscle should occur along the entire length of the muscles and the aponeuroses. This is required to identify swelling, thickening, tenderness, defects and masses if present.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Contusion

- Jumper's Knee

- Femoral Neck Stress Fracture

- Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis[6]

- Previous injury seems not to constitute a risk factor [7]

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

Most acute injuries in the quadriceps muscles can be found easily by the therapist by just letting the patient tell how the injury occurred and doing a quick examination of the quadriceps muscles afterwards. But when the therapist isn’t too sure, he can always consider medical imaging to give a definite answer. Medical imaging tells us for example the exact type and location of the muscle strain.[8]

After obtaining a thorough history, a careful examination should ensue including observation, palpation, strength testing, and evaluation of motion. Strain injuries of the quadriceps may present with an obvious deformity such as a bulge or defect in the muscle belly. Ecchymosis may not develop until 24 hours after the injury. Palpation of the anterior thigh should include the length of the injured muscle, locating the area of maximal tenderness and feeling for any defect in the muscle. Strength testing of the quadriceps should include resistance of knee extension and hip flexion. Adequate strength testing of the rectus femoris must include resisted knee extension with the hip flexed and extended. Practically, this is best accomplished by evaluating the patient in both a sitting and prone-lying position. The prone-lying position also allows for optimum assessment of quadriceps motion and flexibility. Pain is typically felt by the patient with resisted muscle activation, passive stretching, and direct palpation over the muscle strain. Assessing tenderness, any palpable defect, and strength at the onset of muscle injury will determine grading of the injury and provide direction for further diagnostic testing and treatment.

There are several types of medical imaging which can be used for muscle strains:

- Radiographs: a positive point about radiographs is that they are good to differentiate the etiology of the pain in the quadriceps muscles. Etiologies can be muscular (muscle strain etc.) or bony (stress fracture etc.).

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound is very often used because it is relatively inexpensive. But it also has a quite big disadvantage, namely the fact that it’s highly operator dependent and requires a skilled and experienced clinician. Another advantage of US is the fact that it has the ability to image the muscles dynamically and to asses for bleedings and hematoma formation via Doppler.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI is a good way to give detailed images of the muscle injury. If it’s not clear whether it’s a contusion or a strain, the therapist must rely on the story the patient told him about how the injury occurred. And then he can deduce whether it’s the one or the other.[9]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

- Voluntary activation by superimposing percutaneous electrical stimulation on to an isometric quadriceps. When the muscle is fully activated, the electrical stimulation does not generate additional force above the voluntary contraction.

- Muscle test: quadriceps force and ROM. There are 5 grades of manual testing: Grade 0 is the lowest grade where the patient isn’t able to do anything . Grade 5 is the highest grade where the patient can move his leg against a maximum resistance given by the therapist. [10]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Ely’s test :The Ely’s test (or Duncan-Ely test) is used to assess rectus femoris spasticity or tightness.

Technique[edit | edit source]

The patient lies prone in a relaxed state. The therapist is standing next to the patient, at the side of the leg that will be tested. One hand should be on the lower back, the other holding the leg at the heel. Passively flex the knee in a rapid fashion. The heel should touch the buttocks. Test both sides for comparison. The test is positive when the heel cannot touch the buttocks, the hip of the tested side rises up from the table, the patient feels pain or tingling in the back or legs.

Other evaluation methods are:

• Hamstrings/Quadriceps ratio (H vs. Q) - A calculation in which the strength (peak torque) of the hamstring muscles in eccentric motion is divided by the strength of the quadriceps in a concentric motion: Asymmetries/dysbalances in the functional H/Q ratio was shown to significantly impact injury incidence .

• Range of motion decrease (ROM)

• Muscle strength loss

• Skin temperature

• Pain (under pressure)

• Bruises (ecchymosis)

• Sore end-feel

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

The use of NSAID's ( nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) is still contorversial, their benefit, cost and potential adverse effects may be taken into consideration. If used, it should be during the inflamatory period (48h-72h) [2]

Surgical Intervention may be necessary if there is a complete quadriceps muscle rupture.

There has been an experimental study (1998) about the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The therapy should be applied during the early phase of the repair of the injured muscle.This therapy could accelerate the repair of the injured muscle.But we should be careful to extend these findings to clinical practice, because there haven’t been any clinical studies to show the beneficial effects of this therapy in the treatment of muscle or other types of soft tissue injuries in athletes yet.[11][9]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

One should exercise extreme caution in considering surgical intervention in the treatment of muscle injuries, as a properly executed nonoperative treatment results in a good outcome in virtually all cases. In fact, the phrase muscle injuries do heal conservatively could be used as a guiding principle in the treatment of muscle traumas.

Having said that, there are certain highly specific indications in which surgical intervention might actually be beneficial.

Indications[edit | edit source]

- large intramuscular hematoma(s),

- a complete (III degree) strain or

- tear of a muscle with few or no agonist muscles, or

- a partial (II degree) strain if more than half of the muscle belly is torn.

- surgical intervention should be considered if a patient complains of persisting extension pain (duration, >4-6 months) in a previously injured muscle, particularly if the pain is accompanied by a clear extension deficit. In this particular case, one has to suspect the formation of scar adhesions restricting the movement of the muscle at the site of the injury, a phenomenon that often requires surgical deliberation of the adhesions.

If surgery is indeed warranted in the treatment of an acute skeletal muscle injury, the following general principles are recommended:

Principles[edit | edit source]

- The entire hematoma and all necrotic tissue should be carefully removed from the injured area.

- One should not attempt to reattach the ruptured stumps of the muscle to each other via sutures unless the sutures can be placed through a fascia overlying the muscle.Sutures placed solely through myofibers possess virtually no strength and will only pierce through the muscle tissue.

- Loop-type sutures should be placed very loosely through the fascia, as attempts to overtighten them will only cause them to pierce through the myofibers beneath the fascia, resulting in additional damage to the injured muscle. It needs to be emphasized here that sutures might not always provide the required strength to reappose all ruptured muscle fibers, and accordingly, the formation of empty gaps between the ruptured muscle stumps cannot always be completely prevented.

- As a general rule of thumb, the surgical repair of the injured skeletal muscle is usually easier if the injury has taken place close to the MTJ, rather than in the middle of the muscle belly, because the fascia overlying the muscle is stronger at the proximity of the MTJ, enabling more exact anatomical reconstruction.

- In treating muscle injuries with 2 or more overlying compartments, such as the muscle quadriceps femoris, one should attempt to repair the fascias of the different compartments separately, beginning with the deep fascia and then finishing with the repair of the superficial fascia.

- After surgical repair, the operated skeletal muscle should be supported with an elastic bandage wrapped around the extremity to provide some compression (relative immobility, no complete immobilization, eg, in cast, is needed).

- Despite the fact that experimental studies suggest that immobilization in the lengthened position substantially reduces the atrophy of the myofibers and the deposition of connective tissue within the skeletal muscle in comparison to immobilization in the shortened position, the lengthened position has an obvious draw-back of placing the antagonist muscles in the shortened position and, thus, subjecting them to the deleterious effects of immobility.

After a careful consideration of all the above-noted information, we have adopted the following postoperative treatment regimen for operated muscle injuries.

Post operative treatment[edit | edit source]

- The operated muscle is immobilized in a neutral position with an orthosis that prevents one from loading the injured extremity.

- The duration of immobilization naturally depends on the severity of the trauma, but patients with a complete rupture of the m. quadriceps femoris or gastrocnemius are instructed not to bear any weight for 4 weeks,

- Although one is allowed to cautiously stretch the operated muscle within the limits of pain at 2 weeks postoperatively.

- Four weeks after operation, bearing weight and mobilization of the extremity are gradually initiated until approximately 6 weeks after the surgery, after which there is no need to restrict the weightbearing at all.

Experimental studies have suggested that in the most severe muscle injury cases, operative treatment may provide benefits. If the gap between the ruptured stumps is exceptionally long, the denervated part of the muscle may become permanently denervated and atrophied. Under such circumstances, the chance for the reinnervation of the denervated stump is improved, and the development of large scar tissue within the muscle tissue can possibly be at least partly prevented by bringing the retracted muscle stumps closer together through (micro) surgical means. However, in the context of experimental studies, it should be noted that the suturation of the fascia does not prevent contraction of the ruptured muscle fibers or subsequent formation of large hematoma in the deep parts of the muscle belly.

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

When a quadriceps muscle strain occurs during a competition or training, it is important to react immediately. In the 10 minutes following the trauma one needs to put the knee of the affected leg immediately in 120° of flexion.[2][12] This avoids potential muscle spasms, reduces the hemorrhage and minimizes the risk of developing myositis ossificans[12]

If the knee is left in extension the healing process will be slower and more painful because the quadriceps will start to heal in a shortened position.[12] The rest of the therapy during the healing process is based on the RICE therapy. This includes:

- Rest,

- Ice treatment for 20 minutes every 2-3 hours,

- Compression with an ACE bandage

- Elevation.[12]

Rest prevents worsening of the initial injury. Ice or cold application is thought to lower intra-muscular temperature and decrease blood flow to the injured area. Compression may help decrease blood flow and accompanied by elevation will serve to decrease both blood flow and excess interstitial fluid accumulation. The goal is to prevent hematoma formation and interstitial edema, thus decreasing tissue ischemia. However, if the immobilization phase is prolonged, it will be detrimental for muscle regeneration.[13]

By placing the injured extremity to rest the first 3-7 days after the trauma, we can prevent further retraction of the ruptured muscle stumps (the formation of a large gap within the muscle), reduce the size of the hematoma, and subsequently, the size of the connective tissue scar.[9] The elevation of an injured extremity above the level of heart results in a decrease in hydrostatic pressure, and subsequently, reduces the accumulation of interstitial fluid, so there is less swelling at the place of injury. But it needs to be stressed that there is not a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the RICE-principle in the treatment of soft tissue injury.

Regarding the use of cold on injured skeletal muscle, it has been shown that early use of cryotherapy is associated with a significantly smaller hematoma between the ruptured myofiber stumps, less inflammation and tissue necrosis, and somewhat accelerated early regeneration.[13][14] But according to the most recent data on topic (2007), icing of the injured skeletal muscle should continue for an extended period of time (6 hours) to obtain substantial effect on limiting the hemorrhaging and tissue necrosis at the site of the injury.[15]

During the first few days after the injury, a short period of immobilization accelerates the formation of granulation tissue at the site of injury, but it should be noted that the duration of reduced activity (immobilization) ought to be limited only until the scar reaches sufficient strength to bear the muscle-contraction induced pulling forces without re-rupture. At this point, gradual mobilization should be started followed by a progressively intensified exercise program to optimize the healing by restoring the strength of the injured muscle, preventing the muscle atrophy, the loss of strength and the extensibility, all of which can follow prolonged immobilization.[16]

This hasn’t been proved in scientific literature, but it is commonly used by physiotherapists and doctors. Before a patient turn back to normal activities, he or she should do some exercises and stretching to reinforce the quadriceps and hamstrings- muscle. The exercises can be isometric, isotonic, isokinetic and in a later stage of the revalidation sport- or ADL-specific.[2] An overview of the types of exercises:

- Isometric: muscle contraction without change in muscle length (mostly against a fixed object).

- Isotonic: muscle contraction against a constant resistance with a shortening/lengthening of the muscle.

- Isokinetic: muscle contraction by a specific movement (e.g. flexion-extension of the knee).

All of these exercises should be done in a range of motion that is pain-free. These strengthening exercises will also help in preventing from a new strain injury.[2]

Key research[edit | edit source]

Kary, Joel M. "Diagnosis and management of quadriceps strains and contusions." Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine 3.1-4 (2010): 26-31. (level 2C)

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Techniques for Assessing a Suspected Quadriceps Strain:

- Quadriceps exercises:

Clinical bottom line[edit | edit source]

Acute strain injuries of the quadriceps commonly occur in athletic competitions such as soccer, rugby, and football. These sports regularly require sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the quadriceps during regulation of knee flexion and hip extension. Higher forces across the muscle–tendon units with eccentric contraction can lead to strain injury. Excessive passive stretching or activation of a maximally stretched muscle can also cause strains. Of the quadriceps muscles, the rectus femoris is most frequently strained. Several factors predispose this muscle and others to more frequent strain injury. These include muscles crossing two joints, those with a high percentage of Type II fibers, and muscles with complex musculotendinous architecture. Muscle fatigue has also been shown to play a role in acute muscle injury.

Therapy is bases on 3 principles:

1. RICE

2. knee mobilisation

3. Training of the quadriceps functions

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

-The Effectiveness of Injury Prevention Programs to Modify Risk Factors for Non-Contact Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Hamstring Injuries in Uninjured Team Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review.(2015)

- http://www.physio-pedia.com/Muscle_Strain

References

[edit | edit source]

(24) Hurley, Michael V., Joanne Rees, and Di J. Newham. "Quadriceps function, proprioceptive acuity and functional performance in healthy young, middle-aged and elderly subjects." Age and ageing 27.1 (1998): 55-62. (Level 3A)

(25) Marks, M. C., and H. G. Chambers. "Clinical utility of the Duncan‐Ely test for rectus femoris dysfunction during the swing phase of gait." Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 45.11 (2003): 763-768. (Level 1A)

(26) Kalimo H, Rantanen J, Järvinen M. Muscle injuries in sports. Baillieres Clin Orthop. 1997;2: 1-24 (Level 2C)

(27) Hamilton, Bruce. "Hamstring muscle strain injuries: what can we learn from history?." British journal of sports medicine 46.13 (2012): 900-903. (Level 5)

(28) The early management of muscle strains in the elite athlete: best practice in a world with a limited evidence basis. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:158–9. (Level 1B)

(29) Natsis, Konstantinos, et al. "Bilateral rectus femoris intramuscular haematoma following simultaneous quadriceps strain in an athlete: a case report." Journal of medical case reports 4.1 (2010): 56. (level 4 : case report (series)

(30) Taylor, Clare, Rathan Yarlagadda, and Jonathan Keenan. "Repair of rectus femoris rupture with LARS ligament." BMJ case reports 2012 (2012): bcr0620114359. (level 4: case series)

(31) (Machotka, Zuzana, et al. "Anterior cruciate ligament repair with LARS (ligament advanced reinforcement system): a systematic review." Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology 2.1 (2010): 1.) (level 1A)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kary JM. Diagnosis and management of quadriceps strains and contusions. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2010 Oct 1;3(1-4):26-31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Almekinders LC. Anti-inflammatory treatment of muscular injuries in sport. An update of recent studies. Sports Med. Dec 1999;28(6):383-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Best TM. Soft-tissue injuries and muscle tears. Clinics in sports medicine. 1997 Jul 1;16(3):419-34.

- ↑ Beiner JM, Jokl P. Muscle contusion injuries: current treatment options. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2001 Jul 1;9(4):227-37.

- ↑ Thigh Strain http://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/sport-injuries/thigh-pain/quadriceps-strain (Last accessed 22 july 2018)

- ↑ Medscape. Drugs And Diseases: Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/91596-overview (accessed November 23, 2014)

- ↑ Fousekis K, Tsepis E, Poulmedis P, Athanasopoulos S, Vagenas G. Intrinsic risk factors of non-contact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. British journal of sports medicine. 2010 Nov 1:bjsports77560.

- ↑ Tero AH Järvinen, Markku Järvinen, Hannu Kalimo; Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury; Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 2013; 3 (4): 337-345 (2A)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Järvinen TAH, Järvinen TLN, Kääriäinen M, Kalimo H, Järvinen M. Muscle Injuries Biology and Treatment. The American Journal of Sports Medicine Vol. 33, No. 5, 2005 745-764 (2A)

- ↑ Hurley MV, Rees J, Newham DJ. Quadriceps function, proprioceptive acuity and functional performance in healthy young, middle-aged and elderly subjects. Age and ageing. 1998 Jan 1;27(1):55-62.

- ↑ Best TM, Loitz-Ramage B, Corr DT, Vanderby R. Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of acute muscle stretch injuries: results in an animal model. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:367-372.) (2A)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Michael A Herbenick, MD; Michael S Omori, MD; Paul Fenton, MD. Contusions, 2009 (A)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hurme T, Rantanen J, Kalimo H. Effects of early cryotherapy in experimental skeletal muscle injury. Scand J Med & Sci Sports 1993;3:46-51. (2B)

- ↑ Deal DN, Tipton J, Rosencrance E, Curl WW, Smith TL. Ice reduces edema. A study of microvascular permeability in rats. J Bone & Joint Surg 2002;84-A:1573-1578. (2A)

- ↑ Schaser K-D et al., Prolonged superficial local cryotherapy attenuates microcirculatory impairment, regional inflammation, and muscle necrosis following closed soft tissue injury in rats. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:93-102. (2B)

- ↑ Delos D., et al. Muscle Injuries in Athletes: Enhancing Recovery Through Scientific Understanding and Novel Therapies. Sports Health 2013; 5(4): 346-352. (1A)

- ↑ Techniques for Assessing a Suspected Quadriceps Strain. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lv_uRBi_ZS0 [last accessed 22 july 2108]

- ↑ Quadriceps exercises . Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPvgiRjsEIs [last accessed 22 july 2018]