Sacroiliitis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

* Although not always obvious, inspection can reveal pelvic asymmetry. | |||

* Measurement of the limbs can rule out a leg-length discrepancy. Inspect the spine for any abnormal curvatures or rotational abnormalities. | |||

* Typically the range of motion, neurologic, and strength testing are unremarkable although the patient may experience pain during some of these tests. | |||

Special provocative tests can be very helpful in reproducing the patient’s pain: | |||

“Fortin finger sign”- reproduction of pain after applying a deep palpation with the four-hand fingers posteriorly at the patient's SI joint(s). | |||

[[FABER Test|FABER]] test- reproduction of pain after flexing the hip while also abducting and externally rotating the hip. | |||

Sacral distraction test- reproduction of pain after applying pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine. | |||

Iliac compression test- reproduction of pain after applying pressure downward on the superior aspect of the iliac crest. | |||

[[ | [[Gaenslen Test|Gaenslen]] test- reproduction of pain after having the patient flex the hip on the unaffected side and then dangle the affected leg off the examining table. Pressure is then directed downward on the leg to extend further the hip, which causes stress on the SI joint. | ||

Thigh thrust test- reproduction of pain after flexing the hip and applying a posterior shearing force to the SI joint. | |||

Sacral thrust test- reproduction of pain with the patient prone and then applying an anterior pressure through the sacrum. | |||

The likelihood of SI joint mediated pain increases as the number of positive-provocative tests increase. | |||

# | |||

The sacroiliac joint can be examined by [[Sacroiliac joint|Special tests]]. | The sacroiliac joint can be examined by [[Sacroiliac joint|Special tests]]. | ||

Revision as of 07:58, 13 June 2020

Original Editors - Charlotte Fastenaekels

Top Contributors - Annelies Noppe, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Stéphanie Dartevelle, Charlotte Fastenaekels, Matthias Bossche, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Sally Ngo, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Nicole Hills, Shreya Pavaskar, Rachael Lowe, Kai A. Sigel, Claire Knott and Wanda van Niekerk Template:Matthias Van den Bossche

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

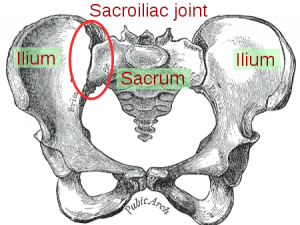

Sacroiliitis is an inflammation of the sacroiliac joint (SI), usually resulting in pain. The sacroiliac joint (SI) is one of the largest joints in the body and is a common source of the buttock and lower back pain. It connects the bones of the ilium to the sacrum.

Sacroiliitis

- Often it is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Can be particularly difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are similar to many other common sources of back pain.

- Often is overlooked as a source of back or buttock pain.

- Pain from this condition often is due to chronic degenerative causes yet relatively uncommon.

- Can be secondary to rheumatic, infectious, drug-related, or oncologic sources.

Some specific examples of non-degenerative conditions that can lead to sacroiliitis are ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthropathy, Behcet's disease, hyperparathyroidism, and various pyogenic sources.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The sacrum articulates with the ilium, which helps to distribute body weight to the pelvis.

The SI joint capsule is relatively thin and often develops defects that enable fluid, such as joint effusion or pus, to leak out onto the surrounding structures[1].

The Sacroiliac Joint

- True diarthrodial joint, the articular surfaces are separated by a joint space containing synovial fluid and enveloped by a fibrous capsule.

- Has unique characteristics not typically found in other diarthrodial joints.

- Consists of fibrocartilage in addition to hyaline cartilage and is characterized by discontinuity of the posterior capsule, with ridges and depressions that minimize movement and enhance stability.

- Well provided with nociceptor and proprioceptors. Receives its innervation from the ventral rami of L4 and L5, the superior gluteal nerve, and the dorsal rami of L5, S1 and S2 or that it is almost exclusively derived from the sacral dorsal rami.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Various conditions result in the inflammation of the SI joint, leading to significant pain.

- Osteoarthritis can cause degeneration of the joint resulting in pathologic articulation and motion leading to this condition.

- Spondyloarthropathies can cause significant inflammation of the joint itself eg Ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, arthritis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease

- Pregnancy is another cause of the inflammation due to the hormone relaxin leading to the relaxation, stretching, and possible widening of the SI joint(s). The increased weight of pregnancy also causes extra mechanical stress on the joint, leading to further wear and tear.

- Trauma can cause direct or indirect stress and damage to the SI joint.

- Pyogenic sacroiliitis is the most frequently reported cause of acute sacroiliitis.

- Pain can originate from the synovial joint but can also originate from the posterior sacral ligaments[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Reports on the prevalence of sacroiliac pain vary widely.

- Some studies report the prevalence as 10% to 25% of those with lower back pain.

- In those with a confirmed diagnosis, the presentation of pain was ipsilateral buttock (94% cases) and midline lower lumbar area (74%).

- Up to 50% of cases have radiation to the lower extremity: 6% to the upper lumbar area, 4% percent to the groin, and 2% percent to the lower abdomen[1]

- Symmetrical sacroiliitis is found in more than 90% of ankylosing spondylitis and 2/3 in reactive arthritis and psoriatic arthritis.

- It is less severe and more likely to be unilateral and asymmetrical in reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, arthritis of chronic inflammatory bowel disease and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy.[3][4]

- The hospital prevalence of sacroiliac diseases is 0,55%, the female sex predominates( 82,35%) and the mean age of 25,58 years. Gyneco-obstetric events are the predominant risk factors (47,05%). The etiologie found are bacterial arthritis (82,3%) mainly pyogenic (70,58%), osteoarthritis(11,7%) and ankylosing spondylitis (5,9%) .

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Sacroiliitis commonly presents as lower back pain.

Patients may report

- Pain in one or both buttocks, hip pain, thigh pain, or even pain more distal.

- Pain is worse after sitting for prolonged periods or with rotational movements.

- Intolerance with lying or sitting and increasing pain while climbing stairs or hills.

- Poor sleep habits and unilateral giving way or buckling.

- Pain with position changes or transitional motions (i.e., sit to stand, supine to sit). [5]

- Pain (varies widely) and is commonly described as sharp and stabbing but can also be described as dull and achy.

Important to ascertain more than just the timing and descriptions of the pain. Ask about a history of inflammatory disorders.

- Obtain a thorough review of systems to evaluate for systemic symptoms such as fevers, chills, night sweats, and weight loss. These symptoms are indicative of a more serious process indicating likely systemic illness.Patients report low back pain (below L5), pain in the buttocks and/or pelvis and postero-lateral on the thigh, which may extend down to one or both legs[1].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of acute sacroiliitis is often challenging because of both the relative rarity of this presentation and diverse character of acute sacroiliac pain, frequently mimicking other, more prevalent disorders.

New-onset intense pain is a major clinical manifestation of acute sacroiliitis, pointing to the diagnosis. The diagnosis of acute sacroiliitis is frequently overlooked at presentation. [6] [7]

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Hip tendonitis/fracture

- Piriformis syndrome

- Sacroiliac joint infection

- Trochanteric bursitis[1]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Various inflammatory conditions may cause or contribute to SI joint pain.

- If an inflammatory condition is suspected, consider ordering complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibody, human leukocyte antigen (HLA-B27), and rheumatoid factor. Although cancer is a far less common cause of sacroiliitis, if a cancerous process is suspected, consider ordering labs to assess for malignancy[1].

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

- Conventional radiography remains the first line of imaging despite its poor sensitivity and specificity in early disease. Specific sacroiliac joint views are helpful in the evaluation and comparing both sides of sacroiliac joints.

- Radiograph findings include: sclerosis of the endplates particularly on the iliac side; irregular joint end plates; widening of joint spaces

CT

- CT examinations offer greater sensitivity, accuracy and detailed information compared to plain radiography. However, due to higher radiation exposure, it is not advisable to use CT for diagnosis or follow-up purposes.

Nuclear medicine

- Bone scans demonstrate increased radioisotope activity of the joints and helpful in localising the source of the pain. It is also valuable in excluding stress fractures and other bone pathologies.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) is most effective for persistent, severe disability, while the Roland-Morris is more appropriate for mild to moderate disability.[9] The Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (link) and The Assessment of Pain and Occupational Performance may also be appropriate.

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Although not always obvious, inspection can reveal pelvic asymmetry.

- Measurement of the limbs can rule out a leg-length discrepancy. Inspect the spine for any abnormal curvatures or rotational abnormalities.

- Typically the range of motion, neurologic, and strength testing are unremarkable although the patient may experience pain during some of these tests.

Special provocative tests can be very helpful in reproducing the patient’s pain:

“Fortin finger sign”- reproduction of pain after applying a deep palpation with the four-hand fingers posteriorly at the patient's SI joint(s).

FABER test- reproduction of pain after flexing the hip while also abducting and externally rotating the hip.

Sacral distraction test- reproduction of pain after applying pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine.

Iliac compression test- reproduction of pain after applying pressure downward on the superior aspect of the iliac crest.

Gaenslen test- reproduction of pain after having the patient flex the hip on the unaffected side and then dangle the affected leg off the examining table. Pressure is then directed downward on the leg to extend further the hip, which causes stress on the SI joint.

Thigh thrust test- reproduction of pain after flexing the hip and applying a posterior shearing force to the SI joint.

Sacral thrust test- reproduction of pain with the patient prone and then applying an anterior pressure through the sacrum.

The likelihood of SI joint mediated pain increases as the number of positive-provocative tests increase.

The sacroiliac joint can be examined by Special tests.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy can be very helpful if the pain is due to hypermobility. Therapy can help to stabilize and strengthen lumbopelvic musculature. If the pain is due to immobility, then physical therapy can help increase mobilization of the SI joint.

The patient must be referred to a physiotherapist. Suggest 3 to 4 days bed rest for severe acute cases. For persistent cases (2 to 4 weeks) with severe pain, a sacroiliac joint injection may be recommended to confirm the sacroiliac joint as the source of the pain and to introduce the anti-inflammatory medication directly into the joint. Advise 3 to 4 days of bed rest after the injection. Next it is recommended to continue with the restrictions and begin with flexion strengthening exercises after the pain and inflammation have been controlled. These exercises include side-bends, knee chest pulls and pelvic rocks.[10]

NSAIDs and muscle relaxants can be prescribed during the acute phase of presentations. These are less effective as cases become more chronic.

Real-time image-guided intra-articular anesthetic/steroid injections can be performed for diagnostic and therapeutic effect. If the condition persists (6 to 8 weeks) with no improvement of at least 50 percent, repeat corticosteroid injections. Subsequently begin strengthening exercises including sit-ups and weighted side bends. Start with general conditioning of the back and increase slowly to low-impact walking or swimming. Take up normal activities with proper care of the back.[11]

If the previous treatments do not provide adequate relief, then some providers will consider radiofrequency ablation.

Usually, surgery is reserved as a last resort for patients with chronic pain.

In such cases, one can consider SI joint fusion with SI screws[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Reducing inflammation in the SI-joint and increasing the flexibility of the lumbosacral spine and SI areas are the main goals of treatment. Give advice on proper lifting techniques involving the knees. The patient should also avoid movements such as tilting, twisting and extremes of bending. Maintaining correct posture is necessary, therefore a lumbar support for the office chair and vehicle is advised.[12]

In the early treatment stages heat, cold or alternating cold with heat are effective in reducing pain.[13] Cryotherapy can be used to control the inflammation and pain. This form of treatment can be applied by ice massage or the application of ice packs. Cryotherapy should be applied for no more than 20 minutes, with at least one hour between applications. Ice massages will usually require a shorter treatment time. Thermotherapy can also be used by applying hot packs for a maximum of 20 minutes. This form of therapy is used to control pain, increase circulation and to increase soft tissue extensibility. With the aim of reducing pain, conventional TENS (Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) can also be applied.[14] [15][16]

In the early stage, we can also use a pelvic belt or girdle during exercise and activities of daily living. These SI belts provide compression and reduce SI mobility in hypermobile patients. The belt should be positioned posteriorly across the sacral base and anteriorly below the superior anterior iliac spines. This belt may also be used when this condition becomes chronic (10-12 weeks).[17] [18][19]

Once the acute symptoms are under control, the patient can start with flexibility exercises and specific stabilizing exercises. To maintain SI and lower back flexibility, stretching exercises are principal. These exercises include side-bends, knee chest pulls, and pelvic-rocks with the aim of stretching the paraspinal muscles, the gluteus muscles and the SI joint. After hyperacute symptoms have resolved these kinds of exercises should be started. Each stretch is performed in sets of 20. These exercises should never surpass the patient’s level of mild discomfort.[20]

Specific pelvic stabilizing exercises, postural education and training muscles of the trunk and lower extremities, can be useful in patients with sacroiliac joint dysfunctions. The transversus abdominis, lumbar multifidi muscles and pelvic floor are the muscles that will need most training. Training of transversus abdominis independently of other abdominal muscles is effective to provide more stabilization of the sacroiliac joints and prevent laxity, which can cause low back pain. Therefore it is necessary to teach the patient how to contract the transversus abdominis and multifidus. During this learning process it is necessary to give the patient feedback. Also the specific co-contraction of the transversus abdominus and the multifidus should be included in the revalidation program. The best position to teach the patient to co-contract these muscles is in four point kneeling. When the patient can properly perform this exercise, it is time to increase the intensity by changing the starting position,…

Other examples of exercises may include: modified sit-ups, weighted side-bends and gentle extension exercises.

Strengthening of the pelvic floor muscles is also important because they oppose lateral movements of the coxal bones, which stabilizes the position of the sacrum. Activation of the transversus abdominis and pelvic floor muscles will reduce the vertical sacroiliac joint shear forces and increase the stability of the sacroiliac joint.

After rehabilitation, low-impact aerobic exercises such as light jogging and water aerobics are designated to prevent recurrence.[21] [22][23][24][25]

If the patient has a leg length discrepancy or an altered gait mechanism, the most reliable treatment would be to correct the underlying defect. Sacroiliitis is also a feature of spondyloarthropathies. In this case, this condition should also be treated.[26][27][28][29][30]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Buchanan BK, Varacallo M. Sacroiliitis. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Feb 15. StatPearls Publishing. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448141/ (last accessed 13.6.2020)

- ↑ Stacy L. Forst, PA-C, Michael T. Wheeler, DO, Joseph D. Fortin, DO, and Joel A. Vilensky, PhD, A Focused Review The Sacroiliac Joint: fckLRAnatomy, Physiology and Clinical Significance, Pain Physician. 2006;9:61-68, ISSN 1533-3159

- ↑ J. Braun, J. Sieper and M. Bollow, Review Article Imaging of Sacroiliitis, Section of Rheumatology, Department of Nephrology and Endocrinology, UK Benjamin Franklin, Free University, Berlin; Department of Radiology, UK Charite´ , Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany,©2000 Clinical Rheumatology (A1)

- ↑ Peter Huijbregts, PT, MSc, MHSc, DPT, OCS, MTC, FAAOMPT, FCAMT fckLRSacroiliac joint dysfunction: Evidence-based diagnosis,fckLRAssistant Online Professor, University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, St. Augustine, FL, USA, Consultant, Shelbourne Physiotherapy Clinic, Victoria, BC, Canada,Rehabilitacja Medyczna (Vol. 8, No. 1, 2004)(C)

- ↑ Szadek et al. - Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. The Journal of Pain. 2009: 10:354-‐368.fckLRfckLR== Differential Diagnosis ==fckLRfckLRSeronegative spondyloarthopathies with sacroiliitis vs osteitis condensans ilii<sup><ref>Olivieri I., Gemignani G., Camerini E., Semeria R., Christou C., Giustarini S., Pasero G. Differential diagnosis between osteitis condensans ilii and sacroiliitis. J. Rheumatol. 1990; 17(11): 1504-12.

- ↑ 40. Slipman CW, Whyte WS 2nd, Chow DW, Chou L, Lenrow D, Ellen M (2001) Sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Physician 4(2):143–52

- ↑ Berthelot JM, Labat JJ, Le Goff B, Gouin F, Maugars Y (2006) Provocative sacroiliac joint maneuvers and sacroiliac joint block are unreliable for diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Joint Bone Spine 73(1):17–23

- ↑ Radiopedia Sacroiliitis Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/sacroiliitis (last accessed 13.6.2020)

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ N.A. Dunn et al., Quantitative sacroiliac scintiscanning : a sensitive and objective method for assessing efficacy of nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with sacroiliitis, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 1984, 157-159

- ↑ Kapura et al. - Cooled radiofrequency system for the treatment of chronic pain from sacroiliitis: the first case-series.

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger, Symptomatic efficacy of stabilizing treatment versus laser therapy for sub-acute low back pain with positive tests for sacroiliac dysfunction: a randomized clinical controlled trial with 1 year follow-up, North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network*, EUR MED PHYS 2004

- ↑ Prather H.; Sacroiliac joint pain: practical management; Clin J Sport Med.; 2003;13(4):252-255.

- ↑ Cusi MF; Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfuntion.; J Bodyw Mov Ther.; 2010;14(2):152-161.

- ↑ Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger, Symptomatic efficacy of stabilizing treatment versus laser therapy for sub-acute low back pain with positive tests for sacroiliac dysfunction: a randomized clinical controlled trial with 1 year follow-up, North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network*, EUR MED PHYS 2004

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ Cusi MF; Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfuntion.; J Bodyw Mov Ther.; 2010;14(2):152-161.

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger, Symptomatic efficacy of stabilizing treatment versus laser therapy for sub-acute low back pain with positive tests for sacroiliac dysfunction: a randomized clinical controlled trial with 1 year follow-up, North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network*, EUR MED PHYS 2004

- ↑ Carolyn A. Richardson, Chris J. Snijders, Julie A. Hides, Le´onie Damen, Martijn S. Pas, and Joop Storm. The Relation Between the Transversus Abdominis Muscles, Sacroiliac Joint Mechanics, and Low Back Pain. SPINE 2002; Vol. 27, No.4, p 399–405

- ↑ Davies, Claire C.1; Nitz, Arthur J. Psychometric properties of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire compared to the Oswestry Disability Index: a systematic review. Physical Therapy Reviews, Volume 14, Number 6, December 2009 , pp. 399-408(10)

- ↑ C.A. Richardson; Muscle control-pain control. What would you prescribe?; Manual therapy;1995;2-10

- ↑ J.J.M. Pel; Biomechanical Analysis of Reducing Sacroiliac Joint Shear Load by Optimization of Pelvic Muscle and Ligament Forces; Annals of biomedical engineering; 2008; 36(3): 415–424.

- ↑ J. J. M. PEL, C. W. SPOOR, A. L. POOL-GOUDZWAARD, G. A. HOEK VAN DIJKE, and C. J. SNIJDERS, Biomechanical Analysis of Reducing Sacroiliac Joint Shear Load by Optimization of Pelvic Muscle and Ligament Forces, Department of Biomedical Physics and Technology, Erasmus MC, PO Box 2040, Rotterdam 3000 CA, The Netherlands, Annals of Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 36, No. 3, March 2008 (© 2008) pp. 415–424

- ↑ Steven P. Cohen, REVIEW ARTICLE Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment, MD, Pain Management Divisions, Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD and Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC, ©2005 by the International Anesthesia Research Society

- ↑ Cusi, M.F., Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfunction, Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies (2010), doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2009.12.004fckLR©2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- ↑ Stacy L. Forst, PA-C, Michael T. Wheeler, DO, Joseph D. Fortin, DO, and Joel A. Vilensky, PhD, A Focused Review The Sacroiliac Joint: fckLRAnatomy, Physiology and Clinical Significance, Pain Physician. 2006;9:61-68, ISSN 1533-3159

- ↑ Stuart Porter; Tidy’s physiotherapy; Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 14th edition; 2008; p513-530 (BOOK)