Pelvis

Description[edit | edit source]

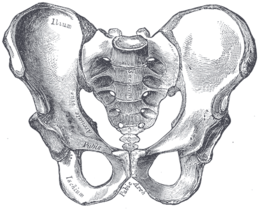

The pelvis consists of the sacrum, the coccyx, the ischium, the ilium, and the pubis.[1][2] The structure of the pelvis supports the contents of the abdomen while also helping to transfer the weight from the spine to the lower limbs.[3] During gait, the joints within the pelvis work together to decrease the amount of force transferred from the ground and lower extremities to the spine and upper extremities.[3]

Bony Pelvis[edit | edit source]

Until puberty, each hip bone consists of three separate bones yet to be fused: ilium, ischium and pubis connected by the tri-radiate cartilage.

The two hip bones are joined anteriorly at the pubic symphysis and posteriorly to the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint. The hip bones incorporate the acetabulum, which articulates with the proximal femur at the hip joint[4].

- In addition to carrying upper body weight, this multi-surfaced pelvic ring can transfer upper body weight to the lower limbs and act as attachment points for lower limb and trunk muscles.

- Furthermore, the bony pelvis protects the pelvic and abdomino-pelvic viscera[5].

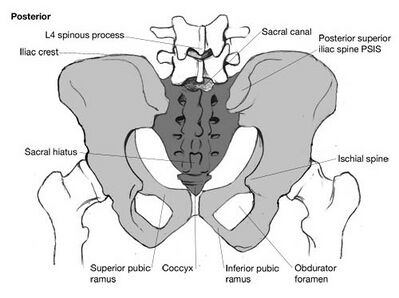

Joint Articulations[edit | edit source]

The pelvic bones make 4 pelvic joints.

- One sacrococcygeal joint posteriorly, a hinge joint between the sacrum and the coccyx.

- 2 sacroiliac joints with the sacrum, the strongest joints in the body.

- 1 symphysis pubis anteriorly, a cartilaginous joint with cartilage in between.

Other articulation: The pelvis and femur articulate via the acetabulum, at the hip joint.[1]

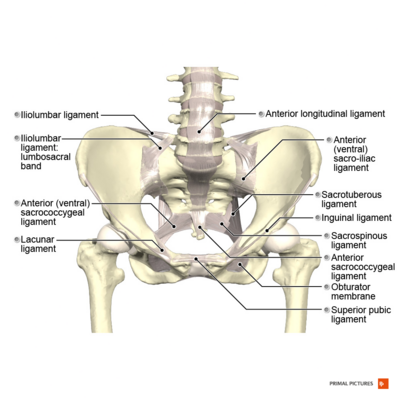

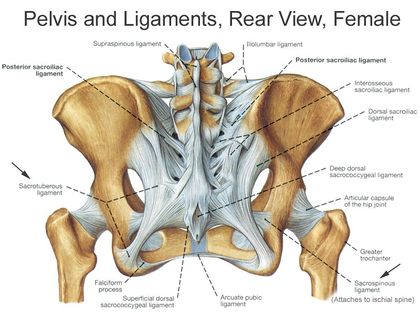

Ligaments of the Pelvis[edit | edit source]

The bony pelvis is held together with the support of the 3 vertebro-pelvic ligaments.

Other ligaments attached to bony pelvis include the sacrococcygeal ligaments, pubic symphysis ligaments, and endopelvic fascia ligament.

Additional ligaments may be found in the female pelvis. These ligaments of the female reproductive system support the internal female genitalia in the female pelvis. See The Uterine And Cervical Ligaments

Muscles[edit | edit source]

There are 36 muscles that attach to the sacrum or hip bone (innominates). The purpose of these muscles is primarily to provide stability to the joint not to produce movement.[6]

Muscles that attach to the sacrum or innominates are:

The Pelvic Cavity[edit | edit source]

The space inside the pelvic bones is called the pelvic cavity.

- Superiorly, the pelvic cavity is continuous with the abdominal cavity.

- Inferiorly, the pelvic cavity is bounded by the Pelvic floor.

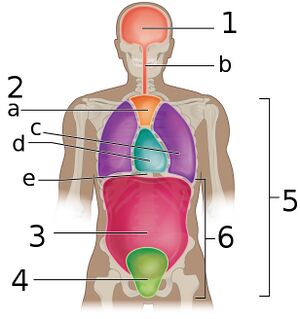

Image: The various cavities of the human body as seen in a frontal projection, with the pelvic cavity labeled 4.

The pelvic cavity is divided into two parts:

- The greater pelvis is part of the abdomen, so it is also referred to as the false pelvis.

- The lesser pelvis is part of the pelvis, so it is also called the true pelvis.

The pelvic cavity functions as housing space for the urinary bladder, the pelvic colon, internal reproductive organs, and rectum. The pelvic cavity additionally houses other internal structures and tissues including muscles, arteries, veins, nerves, and the pelvic connective tissue.[5]

Pelvic Floor[edit | edit source]

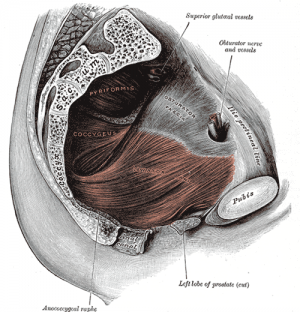

The pelvic floor is the inferior muscular layer of the true pelvic cavity. It separates the pelvic cavity superiorly from the perineum which lies inferior to the pelvic floor. It functions as a boundary of the pelvis and abdominal cavity while supporting the weight of the visceral organs[5].

Image: The pelvic floor.

Sex-specific differences[edit | edit source]

The female pelvis consists of a wider sacrum and a wider subpubic angle when compared to males. The female pelvis’ ischial spines are also less prominent than the male’s ischial spines.[7][8][9] The male pelvis’ sacrum is generally longer and more curved with a narrower sub-pubic arch.[9] In females a wider pelvic aperture is needed as it functions as the birth canal during labour.[7][8][10][11][12]

Associated Conditions[edit | edit source]

The pelvis is of great clinical significance as many issues or disorders can occur[5] eg

- Pelvic fracture

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Pelvic congestion syndrome

- Pelvic endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial tissue starts growing exterior to the uterus within the pelvis.

- The coccyx may give rise to different painful conditions in humans. eg Coccydynia is an inflammatory condition of the coccyx. Traumatic events such as sudden falls and childbirth pressure may cause subluxation or fracturing of the sacrococcygeal joint leading to Coccydynia.

- Pelvic floor dysfunction and muscle weakness may lead to the many conditions see Pelvic Floor Disorders

- Ischial Bursitis

- Pubic Symphysis dysfunction

- Hip Osteoarthritis

- Piriformis Syndrome

- Spondyloarthritis

- Pregnancy related pelvic pain

- Sacroiliitis

Viewing[edit | edit source]

This 13 minute video is on the bony pelvis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 White TD, Black MT, Folkens PA. Human osteology. Academic press; 2011.

- ↑ Lewis CL, Laudicina NM, Khuu A, Loverro KL. The human pelvis: Variation in structure and function during gait. The Anatomical Record 2017;300(4):633-42.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- ↑ Radiopedia Pelvis Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/pelvis-1(accessed 6.11.2021)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Chaudhry SR, Hulaibi FA, Nahian A, Chaudhry K. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pelvis. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 May 24.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482258/(accessed 6.11.2021)

- ↑ Calvillo O, Skaribas I, Turnipseed J. Anatomy and pathophysiology of the sacroiliac joint. Current review of pain 2000;4(5):356-61.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kurki HK. Pelvic dimorphism in relation to body size and body size dimorphism in humans. Journal of Human Evolution 2011;61(6):631-43.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Meindl RS, Lovejoy CO, Mensforth RP, Carlos LD. Accuracy and direction of error in the sexing of the skeleton: implications for paleodemography. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 1985;68(1):79-85.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tague RG. Sexual dimorphism in the human bony pelvis, with a consideration of the Neandertal pelvis from Kebara Cave, Israel. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 1992;88(1):1-21.

- ↑ Rosenberg KR. The evolution of modern human childbirth. American Journal of Physical Anthropology.1992;35(S15):89-124.

- ↑ Lovejoy CO. The natural history of human gait and posture: part 2. Hip and thigh. Gait & posture 2005;21(1):113-24.

- ↑ Abitbol MM. The shapes of the female pelvis. Contributing factors. The Journal of reproductive medicine 1996;41(4):242-50.

- ↑ Anatomy Zone. Bones of the Pelvis. Available from: https://youtu.be/3v5AsAESg1Q [last accessed 27/01/2020]