Sternal Pain - Different Causes

Original Editor - Sofie Van Cutsem

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Sofie Van Cutsem, Lucinda hampton, Evan Thomas, Blessed Denzel Vhudzijena, Oyemi Sillo and Joao Costa

PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS PAGE IS CURRENTLY UNDERGOING UPDATES

Definition/ description[edit | edit source]

Sternal pain is an acute or chronic pain or discomfort felt in the region of sternum and the associated structures.(Dr. C.A. Jenner MB BS, FRCA, Sternal Pain, Nov 2006.)1 Ayloo et al (2013) report that 1-3% of annual visits to a primary care provider in the United States is related to chest pain.[1]

Clinical relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

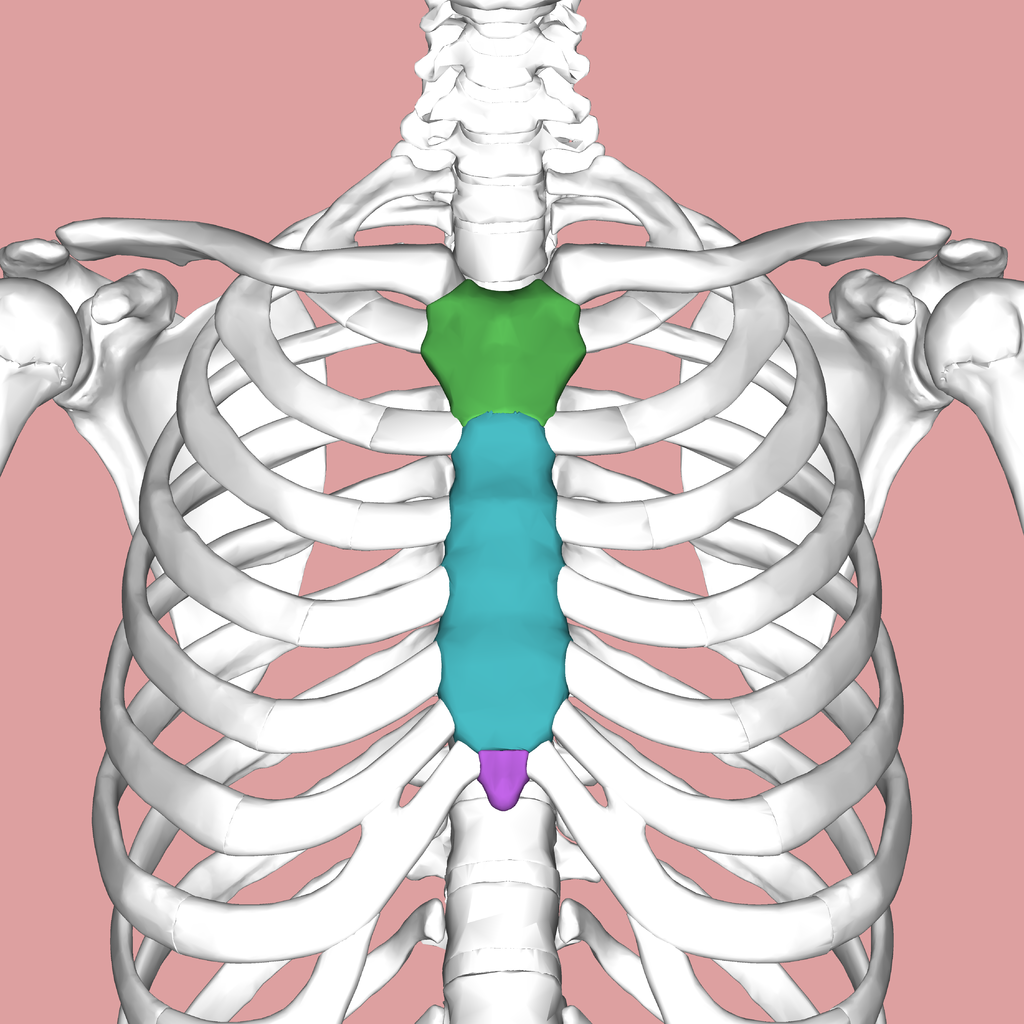

The sternum is a flat bone, located in the center of the anterior thoracic wall. It consists of three segments; the manubrium (uppermost part), the body (middle part) and the xiphoid process (lowest part).(Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, fig. 115 – anterior surface of sternum and costa cartilages.,A. Iqbal, Human anatomy, sternum, 2001) 2,7 The manubrium articulates with the right and left clavicles, the right and left first rib and the upper part of the second costal cartilage.(A. Iqbal, Human anatomy, sternum, 2001)7 The manubrium is quadrangular and lies at the level of the 3rd and 4th thoracic vertebrae. The jugular notch is the thickest part of the bone and is convex anteriorly and concave posteriorly. (A. Iqbal, Human anatomy, sternum, 2001)7 The body of the sternum is longer and thinner. Its margins articulate with the first seven costal cartilages.(Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, fig. 115 – anterior surface of sternum and costa cartilages.,A. Iqbal, Human anatomy, sternum, 2001)2,7 The xiphoid process is the lowest and smallest part of the sternum. It does not articulate with ribs.(A. Iqbal, Human anatomy, sternum, 2001)7 The xiphoid process anchors several important muscles such as rectus abdominus, transversus thoracis and the abdominal diaphragm, a muscle necessary for normal breathing. [2]

Causes of Sternal Pain[edit | edit source]

Cardiovascular causes[edit | edit source]

- Heart valve disease

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Coronary artery disease

- Myocarditis

- Pericarditis

- Aortic dissection

- Amyloidosis

Respiratory causes[edit | edit source]

- Asthma

- Bronchitis

- Bronchiectasis

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Bronchiectasis

- Tracheitis

- Tuberculosis

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pleurisy

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary sarcoidosis

Abdominal and gastrointestinal causes[edit | edit source]

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Pancreatitis

- Peptic ulcers

- Referred pain from the esophagus[1]

Musculoskeletal causes[edit | edit source]

- Sternal fractures

- Clavicular fractures account for 5 to 10 % of all fractures and are most common in children and young adults. (S. Mozes, Family practice notebook, LLC, 2011. [3] [4] The typical mechanism is a fall on the lateral shoulder and upper arm during contact sport. This type of fracture can also occur during a fall on an outstretched arm or elbow or by direct trauma to the clavicle. (S. Mozes, Family practice notebook, LLC, 2011.) 8

- Traumatic rib fractures[1]

- Stress fractures of the rib[1] (https://journals.lww.com/nuclearmed/Abstract/2004/10000/Rib_Stress_Fractures.2.aspx)

- Sternoclavicular joint disorders

- Costochondritis:[1] an inflammatory condition affecting costochondral junctions or chondrosternal joints. In 90% of patients, more than one area is affected and the most commonly affected areas are the second to fifth junctions. [5] Those affected are typically over the age of 40.[5] Clinical signs include localized pain on palpation which may radiate on the chest wall. No swelling occurs with this condition.[5] Recent illness involving coughing and recent strenuous exercise or upper extremity usage can cause this type of inflammation.

- Tietze syndrome:[1] a rare inflammatory condition affecting a single costal cartilage (usually the second or third).[5] Those affected are typically under the age of 40. Localized pain and swelling are found with this condition. It can be caused by infection (particularly from chest wall trauma), neoplasms or rheumatological conditions.[5]

- Inflammatory joint disease (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis) of the sternoclavicular, sternomanubrial or shoulder joints[5][6]

- Fibromyalgia:[1] a rheumatological condition that can cause persistent and widespread pain including symmetrical tender points at the second costochondral junction as well as the neck, back hip and extremities.[5]

- General myalgia related to a history of chest trauma or recent onset of strenuous exercise to upper body (e.g. rowing). It may be bilateral and affecting multiple costochondral areas. Local muscle groups may also be tender to palpation.[5]

- Xiphodynia (or painful/hypersensitive xiphoid syndrome): a condition involving referral of pain to the chest, abdomen, throat, arms and head from an irritated xiphoid process.[1][7] While xiphodynia is usually insidious in nature, trauma may precipitate the syndrome. Acceleration/deceleration injuries, blunt trauma to the chest, unaccustomed heavy lifting and aerobics have been known to lead to the condition.[7] This is a diagnosis of exclusion and typically managed using pain medication.[1] In more persistent cases, corticosteroids or lidocaine may be injected and in the most severe cases, the xiphoid cartilage may be surgically excised.[1]

- Pectoral muscle ruptures: a relative uncommon injury that mostly occurs in male athletes between 20 and 40 years of age.[8] Strenuous athletic activity (e.g. football, water-skiing, wrestling) and weight-lifting (particularly the bench press) are the most common activities associated with this injury.[8] **Forced abduction against resistance, involuntary contraction, and severe traction on the arm. move from maximal eccentric contraction to concentric contraction. steroid use may make the muscle more susceptible to rupture.

- Injuries to other muscles such as the intercostals, serratus anterior, internal oblique, external oblique.[1] Typically these strains occur acutely in response to trauma or overuse.[1]

- Precordial catch syndrome (Texidor’s Twinge)[1]: an uncommon paediatric condition featuring episodes of sharp stabbing pain usually in the region of the left parasternal region or the cardiac apex.[1][9] The pain is typically provoked in slouched positions and is worsened by deep breathing.[1] The condition is thought to be related to spasm of the intercostal muscle(s) but no tenderness is noted on palpation.[1]

- Slipping rib syndrome[1]: a relatively rare paediatric condition in which hypermobility of a rib causes recurrent focal and unilateral chest pain.[5] [10] A recurrent 'popping' sensation may also be reported.[10] Laxity in the sternocostal, costochondral, costovertebral and/or costotransverse ligaments allow for increased mobility and susceptibility to trauma.[10] In classic SRS, the 8th to 10th ribs are most commonly affected but a rarer variant affects the sternocostal cartilage of one of the 1st to 7th ribs.[10] Pain is reproduced with movement that stresses the affected area as well as palpation and a "hooking" manoeuvre of the affected rib (hooking the fingers under the rib and pulling it anteriorly).[1][10] Surgical excision is reported to be a curative treatment.[10] Non-invasive approaches for less severe presentations include reassurance, analgesics, strapping and avoidance of provocative movements.[1] This condition is rare in adults but may be seen in athletes who perform repetitive trunk movements.[1]

- Post-surgical****

- Osteomyelitis; an inflammation due to infection of the bone or bone marrow (Management of sternal osteomyelitis and mediastinal infection following median sternotomy.)

Referred Pain[edit | edit source]

From the;[1]

- Shoulders

- Cervical spine

- Thoracic spine including thoracic disc herniation[1]

- Structures below the diaphragm

Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Breast cancer

- Lung cancer

- Lymphoma

- Bone cancer

- Skin cancer[1]

Other[edit | edit source]

- Anxiety and depression - found to be correlated with atypical chest pain but it is unknown whether mental health issues are a cause or a consequence[6] ***

- Vitamin D deficiency, possibly due to defective bone mineralization[1]

- Herpes zoster[1]

- SAPHO Syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis)[1]

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

The presentation of a patient with sternal pain depends on the specific cause of the pain. All patients presenting with chest pain should be screened for potential cardiac sources.

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

A patient who is older than 35 years of age, has a history or risk of coronary artery disease or presents with cardio-pulmonary symptoms should have electrocardiography and possibly a chest x-ray.[5] Cardiac stress testing may also be required to fully rule in or rule out a cardiac dysfunction.[1]

A patient with fever, cough, chest wall swelling or other respiratory findings on history or examination should also have a chest x-ray.[5] Chest x-rays are also used to rule in/out rib fractures.[1] CT scans should only be done when neoplasms are strongly suspected.[5] Nuclear scintigraphy (organ scanning) may be positive with costochondritis but the test is not specific to that condition.[5] Blood testing for rheumatoid factor and C-reactive protein (CRP) may be indicated if a rheumatological condition is suspected.[6] MR imaging and/or ultrasound can help to assess the extent of a muscle rupture and if surgical repair is indicated.[1][8]

It is important that once a diagnosis of acute cardiopulmonary disease is ruled out, patients that presented in hospital with atypical chest pain are followed up with by health care professionals. Persistent pain, poor quality of life and inability to return to work are common in this cohort yet in a study published in 2003, the authors found that musculoskeletal diagnoses are most common when patients are reassessed one year following discharge without a diagnosis for their atypical chest pain.[6][13] Similarly, Ayloo et al (2013) report that in patients presenting with chest pain to a primary care practitioner in the United States, 21-49% of diagnoses are musculoskeletal in nature.[1] Further assessment and management are therefore important with these types of cases. Reassurance that life-threatening illness such as myocardial infarction has been ruled out is important to reduce the risk of persistent anxiety related to the chest pain.[13]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Cardiopulmonary - observation, breathing rate, heart rate, blood pressure

Chest pain persisting longer than 12 hours and tenderness on palpation of the anterior chest wall are strong clinical indicators of a musculoskeletal cause of sternal pain.[6] Active movements such as deep breathing (to expand the thorax) and elevation of the upper extremities may reinforce a musculoskeletal diagnosis.[5][8] Pain during inspiration would be expected in the presence of a rib fracture, along with painful chest and upper extremity movements and pain on palpation and/or gentle percussion.[1]

Resisted testing may pick up true muscular weakness or neurogenic weakness.[1][8] Altered sensory testing and peripheral reflexes in addition to neurogenic weakness may be indicative of thoracic or lower cervical nerve root involvement. Asymmetry, swelling and bruising (either on the chest or into the axilla and arm) may be observed in the presence of severe muscle injuries such as a pectoralis major rupture and the patient may have felt a 'pop' at the moment of onset.[8] For more minor strains, the following information can help to differentiate between structures;[1]

| Muscle | Mechanism | Presentation & Examination | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercostal(s) | Excessive exertion of untrained muscles in activities such as coughing, chopping wood or overhead painting and in sports with a lot of upper body exertion such as rowing. | Pain/tenderness on palpation of intercostal(s).

Pain with deep inspiration and coughing. |

|

| Pectoralis major and/or minor | Direct blow.

Indirect trauma e.g. forceful eccentric contraction when muscle is already under full tension (more common in sports such as weight lifting and rugby), or forced abduction with external rotation or extension (such as in a fall or recreational weight-lifting). |

Sudden arm or shoulder pain reported, possibly with a 'pop.'

+/- Swelling and bruising. +/- Loss of axillary fold, asymmetry, palpable defect in muscle belly. +/- Loss of arm adduction |

|

| Internal and External Oblique | Muscle lengthening followed by sudden eccentric contraction.

Uncommon injury but when present, typically associated with swimming, javelin throwing, rowing and ice hockey. It is also seen in the non-bowling arm of a cricket fast bowler. |

Pain on palpation of lower four costal cartilages.

Increased pain with resisted trunk side bend towards the injured side. |

|

| Serratus Anterior | Overuse in activities such as weight lifting and rowing | Pain reproduced on resisted scapular protraction |

Questions regarding morning stiffness and other areas of pain or dysfunction as well as general observation of joints may raise the index of suspicion of a rheumatological cause.[5]

Medical management[edit | edit source]

The management of a patient with sternal pain depends on the specific cause of the pain. In the presence of diagnosed joint inflammation, acetaminophen, NSAIDs, local steroid injections or topical analgesics may be indicated.[5][6][13] Systemic arthropathies such as rheumatoid arthritis may require medications such as methotrexate while anti-depressants and pain medication such as gabapentin may be indicated for a diagnosis of fibromyalgia.[5][6]

Rib fracture - Pain management (e.g. analgesics) and relative rest for the first three weeks post-injury followed by gradual return to activity (particularly overhead activities). further investigation to rule out injury to underlying organs may be indicated, particularly in the presence of multiple rib fractures or single fractures to the 1st to 4th or 11th and 12th ribs.[1] In cases of paediatric rib fractures, child abuse should be suspected because typical traumas that children undergo do not lead to this type of injury, thus appropriate referrals/notifications should be made.[1]

Psychological management such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is indicated in the presence of anxiety and/or depression that may be magnifying pain and disability.[6]

Surgical repair is recommended for complete tears of pectoralis major unless a patient is older and/or sedentary such that a repaired muscle is not necessary for function of normal ADLs.[8] Surgery is not typically indicated for proximal tears at the sternoclavicular origin or for partial tears.[8] Repairs have been documented as long as 13 years following rupture with outcomes comparable to early repairs.[8]

Post-surgical Rehabilitation[8][edit | edit source]

- Sling for 4-6 weeks with particular avoidance of active flexion, abduction and external rotation

- Passive pendulum exercises started immediately following surgery

- Passive flexion to 130° allowed immediately following surgery

- At 6 weeks, gentle PROM is started in all directions and gradually progressed until full range is regained

- Gentle peri-scapular strengthening is also initiated at 6 weeks

- Isometric strengthening is also started at 6 weeks with the exception of shoulder adduction, internal rotation and horizontal adduction

- At 3 months, straight plane strengthening of shoulder adduction, internal rotation, and horizontal adduction using pulleys and bands is initiated. Rotator cuff and peri-scapular strengthening is progressed as tolerated

- At 6 months, push-ups and dumbbell bench presses are initiated at low loads but with high repetitions

- Between 9 and 12 months, return to full activities occurs but high low bench press is discouraged indefinitely

Physical therapy management[edit | edit source]

Rib fracture - pain management, deep breathing exercises to maintain appropriate lung function and health, relative rest for the first three weeks post-injury followed by gradual return to activity (particularly overhead activities).[1]

Relative rest for acute myalgia[5]

FM - graded exercise[5]

Muscle strain - reassurance, pain control (e.g. analgesics, heat), avoidance of aggravating activities. A progressive strengthening program and gradual return to activitiy Consider referral for injections of lidocaine or corticosteroids in persistent cases that do not respond to conservative treatment.[1]

Pectoralis major rupture - initial sling (for comfort), analgesics and rest. Early shoulder mobilization and gentle stretching. Once pain improves and mobility is back to normal (typically around six to eight weeks), strengthening. Education on weight lifting technique to reduce further stress on pectoralis major (e.g. lower weight to no more than 4-6cm above chest wall, narrower grip no more than 1.5 times the biacromial width).[8]

Slipping rib Rest, physiotherapy, intercostal nerve blocks; or, if chronic and severe: surgical removal of hypermobile cartilage segment[5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 Ayloo A, Cvengros T, Marella S. Evaluation and treatment of musculoskeletal chest pain. Prim Care. 2013 Dec;40(4):863-87.

- ↑ Broyles R. The location and purpose of the Xiphoid process [Internet]. Troy: Bright Hub Inc; 2009 [updated 7 March 2017; cited 24 January 2018]. Available from:http://www.brighthub.com/science/medical/articles/57775.aspx

- ↑ Stanley D, Norris SH, Recovery fractures of clavicle treated conservatively. Injury. 1988;19(3):162-4.

- ↑ Pecci M, Kreher J. Clavicle fractures. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):65-70.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 Proulx AM, Zryd TW. Costochondritis; diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(6):617-20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 How J, Volz G, Doe S, Heycock C, Hamilton J, Kelly C. The causes of musculoskeletal chest pain in patients admitted to hospital with suspected myocardial infarction. Eur J Intern Med. 2005;16(6):432-6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Simpson JK, Hawken E. Xiphodynia: A diagnostic conundrum. Chiropr Osteopat. 2007, 15:13.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Petilon J, Carr DR, Sekiya JK, Unger DV. Pectoralis major muscle injuries: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):59-68.

- ↑ Gumbiner CH. Precordial catch syndrome. South Med J. 2003;96(1):38-41.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Bonasso PC, Petrus SN, Smith SD, Jackson RJ. Sternocostal slipping rib syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017 Dec 6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4221-1. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Trevor Minor. Hooking Maneuver - Test for Slipping Rib Syndrome. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j38Sfn_1syU[last accessed 27/01/18]

- ↑ Healthy Fit. What causes pain in the sternum? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g54IcjCq4LA[last accessed 26/01/18]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Spalding L, Reay E, Kelly C. Cause and outcome of atypical chest pain in patients admitted to hospital. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):122-5.