Axillary Nerve Injury

Original Editor - Kimberley Anlauf

Top Contributors - Kimberley Anlauf, Vidya Acharya, Kim Jackson, Amanda Ager, Garima Gedamkar, Samuel Adedigba, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Bianca Camacho, Evan Thomas, 127.0.0.1, Admin, WikiSysop, Leana Louw, Tony Lowe, Michael Gillespie, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Johnathan Fahrner, Claire Knott, Abbey Wright, Jose Antonio Cadena, Peter Zatezalo, Jeremy Brady, Wendy Walker and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

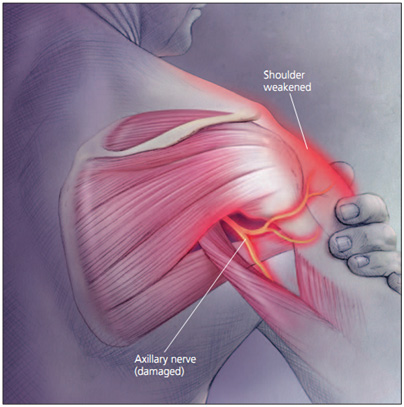

The Axillary nerve (circumflex nerve), is an upper extremity nerve, which is part of the posterior cord (C5-C6), and provides motor innervation to the deltoid and teres minor muscles.

An axillary nerve injury is characterized by trauma to the axillary nerve: from either a compressive force, a traction injury following anterior dislocation of the shoulder,[1][2][3][4] or a forced Abduction movement of the shoulder joint.

An axillary nerve injury can cause signs and symptoms of a localized neuropathy. Signs and symptoms may include:

- Pain to the area of the deltoid and anterior shoulder

- Loss of movement and/or lack of sensation in the shoulder area

- Reported or observed weakness to the deltoid and teres minor muscles (Abduction and external rotation).

A true axillary nerve injury (mononeuropathy -involving a single nerve), should not present with any changes to the local reflexes.

Epidemiology / Etiology[edit | edit source]

- Of all brachial plexus injuries, axillary nerve palsy is quite rare, represents only 3% to 6% of all brachial plexus pathologies.

- Anterior shoulder dislocation is the most common occurring dislocation at the shoulder,[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] which can cause direct trauma (compression or traction) to the axillary nerve.

Statistics associated with an axillary nerve injury:

- Men and women 3:1[5]

- 9-65% of shoulder injuries involve an axillary nerve injury[2][7][8][9][10]

- The incidence of brachial plexus and axillary nerve injuries, increases dramatically following shoulder dislocation in patients ≥50 years of age, if a fracture is associated with the dislocation, as well as if the duration of the dislocation lasts >12 hours[7][8][11][12][13]

- The incidence of nerve injury doubles with the presence of an associated fracture of the humeral head[11]

Mechanism of Injury (MOI)[edit | edit source]

- Anterior or inferior dislocation of humeral head

- Fracture of surgical neck or the humerus

- Forced Abduction of the shoulder

- Falling on outstretched hand (FOOSH injury)

Propagated tension due to overstretching of the axillary nerve over the humeral head during shoulder dislocations may cause elongation of the free portion of the axillary nerve and the increased tension may even result in axillary nerve avulsions from the posterior cord of brachial plexus.[2][8]

The axillary nerve is susceptible to injury at several sites, including the origin of the nerve from the posterior cord, the anterior inferior aspect of the subscapularis muscle and shoulder capsule, the quadrilateral space, and within the subfascial surface of the deltoid muscle.[8]

Nerve Injury Overview[edit | edit source]

As a reminder, nerve regeneration takes place at a rate of an estimated ~1 millimetre (mm) per day. Therefore the recovery can be long and discouraging for the patient at times. Help manage expectations as a clinician with this type of injury.

Neuropraxia[edit | edit source]

- The axon and all 3 connective tissue layers (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) remain intact with a decrease in conduction.

- Comparable to a 1st-degree nerve injury (Sunderland's Classification of Nerve Injury)

Axonotmesis[edit | edit source]

- Axonal damage is present with preservation of the endoneurium.

- The endoneurium acts as a guide for axonal regeneration.

- Comparable to a 2nd degree degree nerve injury .

Neurotmesis[edit | edit source]

- Axonal damage is present.

- Connective sheath damage ranges from partial disruption of the endoneurium to complete disruption of the involved nerve.

- 3rd degree nerve injury= axon and endoneurium are damaged with preservation of the perineurium.

- 4th degree nerve injury= axon, endoneurium, and perineurium are damaged with preservation of the epineurium.

- 5th degree nerve injury= complete disruption of the nerve.

==Characteristics / Clinical Presentation

It is important to note that the clinical presentation of axillary nerve dysfunction is variable and can easily go undetected, as the dislocation or fracture may mask the symptoms.[1][8] Nerve injuries should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis process when a patient reports pain, weakness, or paresthesias.[14]

Subjective Examination

- Generalized mild, dull, and achy pain to the deep or lateral or anterior shoulder, with occasional radiation to the proximal arm. [4][6][15][16]

- Numbness and tingling of the lateral arm and/or posterior aspect of the shoulder (C5-C6 nerve root territory) [4][6][14][8][13][16] in some cases, persisting 2-4 weeks post-injury.

- Feeling of instability of the shoulder .[16]

- Weakness, especially with flexion, abduction, and external rotation. [6][8][15][16]

- Fatigue, especially with overhead activities, heavy lifting, and/or throwing. [14][13][15]

- May/or may not reveal a history of trauma to the shoulder region. [4][6]

- History of dislocation with soreness persisting ~1week post-injury. [16]

- Easing factors include: rest (arm supported), ice, analgesics, and anti-inflammatory medications. [6][14][17]

Many athletes with an axillary nerve injury may be asymptomatic with incomplete or complete lesions, with the only complaints of weakness and early-onset fatigue with exercise. [4][13]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

An axillary nerve injury with a shoulder dislocation (usually anterior or inferior) can present similarly to or concomitantly with the following conditions: [8][12][15]

1. Unhappy Triad[edit | edit source]

The “Unhappy Triad” consists of a shoulder dislocation that results in both a rotator cuff tear and axillary nerve injury.

- Occurs in 9-18% of anterior shoulder dislocations.[7]

- Risk of an “unhappy triad” with anterior shoulder dislocation increases after the age of 40.[7]

2. Quadrilateral Space Syndrome (QSS)[edit | edit source]

QSS is an uncommon condition which involves the compression of the posterior humeral circumflex artery and the axillary nerve within the quadrilateral space, secondary to an acute trauma or from overuse, especially with overhead sports like throwing and swimming.[17]

- Cardinal Features[17]

- Generalized shoulder pain

- Paresthesias in a nondermatomal pattern

- Point tenderness to the quadrilateral space

- (+) arteriogram findings with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation

- Symptoms are typically present with the arm in an overhead position, especially in late cocking or the early acceleration phases of throwing[17]

3. Posterior cord of the brachial plexus injury[edit | edit source]

4. Cervical Radiculopathy (C5-C6)[edit | edit source]

5. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS)[edit | edit source]

PTS is an uncommon, idiopathic condition, characterized by an acute onset of intense pain, without a mechanism of injury, that subsides within days-weeks, leaving behind residual weakness/paralysis in upper extremity muscles.[18]

- Symptoms are NOT related to cervical movements.

- Aka: Acute brachial neuritis

6. Other possible peripheral nerve involvement (signs / symptoms):[edit | edit source]

Spinal accessory nerve (Inability to ABDuct arm beyond 90 degrees. Pain with shoulder ABDuction)

Long thoracic nerve (Pain on flexing fully extended arm. Inability to flex fully extended arm. Scapular winging starts at 90 degrees of forward flexion)

Suprascapular nerve (Increased pain with forward flexion. Shoulder weakness with partial loss of humeral head control. Pain increases with scapular ABDuction and / or contralateral cervical rotation)

Musculocutaneous nerve (Weak elbow flexion with forearm supinated)

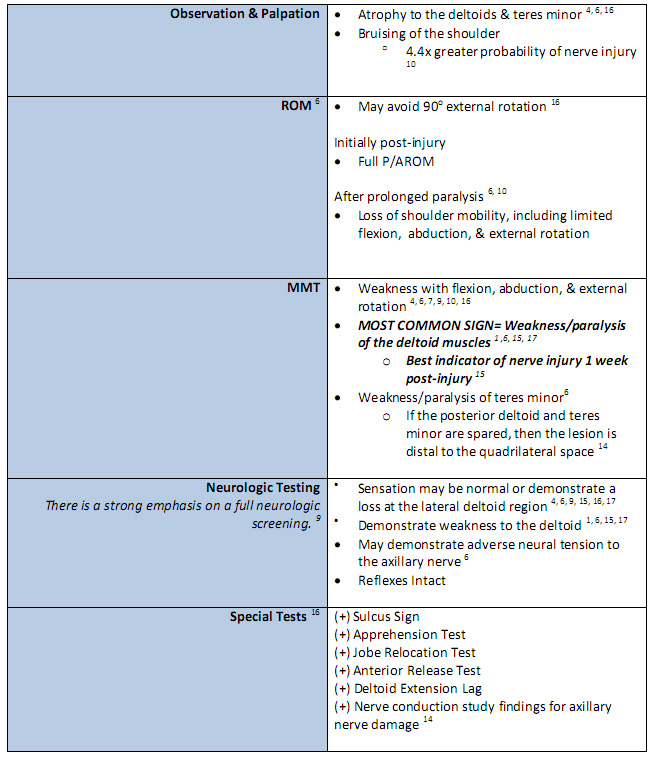

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical examination should begin with a cervical spine screening of all upper extremity dermatomes, myotomes and reflexes.[8][16]

If the patient presents with a recent shoulder dislocation, presence of a radial pulse and sensation and movement of the digits should also be assessed as part of the initial screening.[14]

Table 1: Clinical Evaluation[1][4][6][14][8][11][13][15][16][17]

| [19] | [20] |

It is important to note that the physical examination findings are dependent on the extent of the axillary nerve damage. Furthermore, there is a lack of consensus regarding the ability of a patient to retain normal range of motion and function when presenting with an axillary nerve injury. [8]

Accurate Manual Muscle Testing (MMT) is necessary, as 60% of athletes may be able to elevate the affected arm by compensating with, and recruiting the pectoralis major and supraspinatus muscle groups, and prevent subluxation by utilizing the supraspinatus and long head of the biceps muscles. [4][8][13]

The sensory examination of the axillary nerve has been calculated to have a poor sensitivity (7%), when detecting the presence of axillary nerve injury, emphasizing the need for electrodiagnostic evaluation (nerve conduction test) for a patient with persistent weakness and decreased shoulder function following shoulder dislocation. [7][11]

The duration of recovery from axillary nerve injury can be lengthy, lasting as long as 35 weeks.[11][14]

Clinical Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The best means to confirm a concomitant axillary nerve injury with a shoulder dislocation includes a detailed subjective and objective clinical examinations, along a electromyogram (EMG) study or nerve conduction test.[6]

Diagnostic Imaging[edit | edit source]

EMG[edit | edit source]

The diagnostic test of choice to identify nerve conduction loss is an EMG; However, significant nerve damage may not be identified until 2-3 weeks post-injury.[2][6][8] EMG can distinguish between atrophy secondary to pain or that of a nerve injury.[4] EMG studies also serve as means to track the patient’s progression or regression, throughout the recovery phase; ultimately indicating whether a surgical or conservative treatment approach is needed.

- Neuropraxias (1st degree) nerve injury: [4]

Full recovery occurs 85% to 100% of the time with conservative management within 6 to 12 months.[13][15] Muscle weakness due to the axillary nerve lesion may recover spontaneously as the tissues from the shoulder dislocation heal.[11]

- Axonotmesis (2nd degree) nerve injury:

The recovery rate is near 80%, secondary to the short distance between the site of injury and the muscle endplates. [4][8] Recovery should be evident between 3-4 months post-injury. [4] EMG re-evaluations should be preformed at monthly intervals for signs of regeneration. By 6 months post-injury, if there are no signs of functional return, surgical exploration and possible nerve grafting are recommended. [4]

- Neurotmesis (3rd-5th degree) nerve injury:

Without surgical intervention, there is typically no recovery. [8]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)[edit | edit source]

MRI is rarely used for an initial evaluation of a typical nerve injury. It may be useful if the diagnosis is unclear or if there is evidence of abnormal recovery. An MRI may be useful for a differential diagnosis of the shoulder (muscle tears, tendinopathies, acromio-clavicular separation, labral tears, ligament sprains etc.). It is important to note that a normal MRI result does not rule out a nerve injury.[4]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

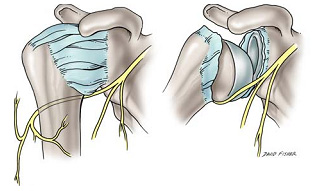

There is uncertainty among clinicians as to the appropriate time for surgical exploration following an isolated axillary nerve injury, with some authors recommending exploration at 3 months post-injury while others recommend at 6 to 12 months post-injury.[8][17] The site of the axillary nerve injury is variable, making both anterior and/or posterior surgical approaches appropriate.[4] If the axillary nerve cannot be repaired without tension, cable grafts are required. Indications for surgery are rare but must be understood by clinicians in order to maximize outcomes and minimize complications.[14]

Indications for surgery:[edit | edit source]

- Suspicion of osteophyte formation or compression in the quadrilateral space.[6]

- No axillary nerve recovery observed by 3 to 4 months following injury.[8]

- No improvements were seen after 3 to 6 months of conservative treatment.[15]

- No EMG/NCV evidence of recovery by 3 to 6 months after injury.[13]

Surgery for shoulder instability in young active patients reduces the likelihood of recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations, therefore reducing the possibility of axillary nerve compromise.[21]

In the rare occasion that surgery is indicated, there are several types of surgeries which can be considered by the patient and his surgeon.[14][13]There is a better prognosis if the surgery is performed within 6 months of the injury but functional improvements can be expected with surgical intervention up to 12 months year after the injury.[13][15] The clinician should be aware of these prognostic correlations between time of injury and time of surgery to maximize the patient's outcome. Overall, the prognosis for a surgical intervention for an axillary nerve injury is very good in 90% of patients. [4]

Surgical Procedures:[edit | edit source]

- Neurolysis -The application of physical or chemical agents to a nerve in order to cause a temporary degeneration of targeted nerve fibers. When the nerve fibers degenerate, it causes an interruption in the transmission of nerve signals.

- Neurorrhaphy -The surgical suturing of a divided nerve.

- Nerve grafting - The sural nerve is commonly used during nerve grafting, not only of the axillary nerve, but in other peripheral nerves injuries as well. Prognosis for the axillary nerve with graft repair is better than other peripheral nerve repairs secondary to its short length. [7][8]

- Neurotization - Also known as nerve transfer. A healthy, but less valuable nerve, or its proximal stump is transferred in order to reinnervate a more important sensory or motor territory that has lost its innervation through irreparable damage to the nerve.

Nonsurgical Reduction[edit | edit source]

Reduction eliminates the need for surgical intervention, and is followed by immobilization and physical therapy management.[22]

- Immobilization for young adult males 4-6 weeks [21][22]

- Immobilization for older patients 7-10 days [11]

- Precaution should be taken during manipulative reduction of a dislocation, in which traction together with rotation or abduction are applied simultaneously, creating extra distraction and increasing the risk of axillary nerve damage. [11]

- Other treatments include: NSAIDS, rest, ice [6][14][17][21]

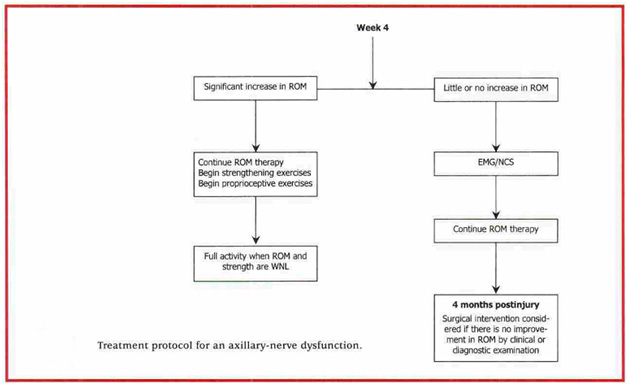

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Current research encompassing treatment and intervention of axillary nerve injuries following shoulder dislocation is limited. The research suggests that the management of the axillary nerve damage following shoulder dislocation is treated in the same manner as treating an isolated dislocation, with an emphasis on strengthening and stimulation of the deltoids and teres minor muscles.[4][12] There should be a great amount of importance placed on allowing ligamentous, capsular, and nervous tissues time to heal while preventing joint stiffness, which could ultimately hinder function greater in the long run.[14][11][12]

Non-Surgical Physical Therapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

0-2 weeks[4][11][12][16][22][23][edit | edit source]

- Shoulder immobilization via sling after reduction. There is insufficient evidence to support whether physical therapy should be initiated during or after immobilization. [5]

- Isometric Strengthening; Dosing: 10 seconds X 6 repetitions X 2 day within limits of pain.

- Joint Mobility:

- Passive Range of Motion (PROM): Flexion, Extension, Abduction, Adduction, Internal Rotation.

- Active Range of Motion (AROM) of all shoulder movements (except external rotation), when pain is maintained at 3/10 or less; Dosing 10 repetitions X 2 day

- Elbow (Flexion, Extension,Pronation, Supination)

- Wrist (Flexion, Extension, Radial/Ulnar deviation)

- Hand (Opening/Closing Fist)

2-4 weeks[edit | edit source]

- Joint Mobility

- Passive/Active Assisted Range of Motion (PROM/AAROM); Dosing 10 repetitions X 2 day: Shoulder (Flexion, Internal Rotation, Adduction)

Avoid end-range ER/ABD until later stages of treatment!

- Active Range of Motion (AROM); Dosing 10 repetitions X 2 day:

- Elbow(Flexion, Extension ,Pronation, Supination);

- Wrist (Flexion, Extension, Radial/Ulnar deviation);

- Hand (Opening/Closing Fist)

- Pendulum Exercises 3 sets x 30 seconds for the glenohumeral joint[12]

- Strengthening of Target Muscles[12]:

- Deltoid: “Neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the deltoid muscle can also be helpful to decrease the extent of deltoid muscle atrophy.” [1][8]Rhomboid Major/Minor

- Serratus Anterior

- Upper/Middle/Lower Trapezius

PRECAUTION: against shoulder ABDuction & flexion beyond 90 degrees, and ER beyond neutral in the first 3 weeks.[12]

Older individuals have lower rates of re-occurrence of shoulder dislocation and an increase in incidence of joint stiffness. Therefore, progressive strengthening and proprioceptive training should be initiated sooner than in younger individuals, who usually begin around week 6. [6][12]

4-6 weeks[edit | edit source]

- D/C sling

- Strengthening Program light resistive exercises [22]

Target muscles: Deltoids, Rotator Cuff muscles, Postural muscles

- Closed Chained Activities:

- Wall push-ups -->Table-->Floor

- Weight Shifts

6 weeks-Discharge [3][21][24][25][edit | edit source]

- Continue ROM, glenohumeral and scapulothoracic stabilization/strengthening exercises, proprioception, and joint mobility, while maintaining optimal conditions for tissue healing

- Begin to initiate sport/job specific activities, progressing to full return as patient’s functional status allows. There is no consensus of when return to sport/work is appropriate following an axillary nerve injury. In general, improvement on the EMG and at least 80% return of deltoid muscle strength is recommended. [3][21]. It has been suggested that return to activity for shoulder dislocation is approximately 12 weeks, and 16 weeks for competitive sports. [24][25]

- Conservative physical therapy treatment can last between 3 to 6 months. It is essential that the physical therapist continuously monitor the progression of axillary nerve reinnervation during treatment and contact the patient’s physician if there are no signs of improvement between 3 to 4 months.[14][8] Note: Progression of these interventions with increased weight or resistance should be based on each individual patient and their level of pain and perceived joint stability throughout a controlled movement.[12]

For examples of therapeutic exercises, see Examples of Therapeutic Exercises in Axillary Nerve Injury Rehabilitation.

Post-Surgical Physical Therapy[edit | edit source]

There is a lack of research to support how long a patient should be immobilized after a surgical repair of the axillary nerve. Current recommendations report that the shoulder should be immobilized for 4 to 6 weeks, after which rehabilitation should focus on increasing shoulder range of motion and strengthening. [17]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

A standardized treatment is not yet known for patients with axillary nerve injury, secondary to a shoulder dislocation. However, immobilization based on age, treatments focused on ROM, strength, neuromuscular re-education, and function all seem to be a recurring theme. With early detection, prognosis for the injured axillary nerve is good due to the short amount of time needed to regenerate and recover.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Allen J, Dean K. Recognizing, managing, and testing an axillary- nerve dysfunction. Athletic Therapy Today. 2002;7(2):28-29.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Apaydin N, Tubbs S, Loukas M, Duparc F. Review of the surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve and the anatomic basis of its iatrogenic and traumatic injury. Springer. 2010;32:193-201.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cutts S, Prempeh M, Drew S. Anterior shoulder dislocation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009:91:2-7.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 Duralde X. Neurologic injuries in the athlete’s shoulder. Journal of Athletic Training. 2000;35(3):316-328.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Handoll HHG, Hanchard NCA, Goodchild LM, Feary J. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic ; anterior dislocation of the shoulder (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. 2006;1:1-26.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Miller T. Peripheral nerve injuries at the shoulder. The Journal of Manipulative Therapy. 1998;6(4)170-183.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Payne M, Doherty T, Sequeira K, Miller T. Peripheral nerve injury associated with shoulder trauma: a retrospective study and review of literature. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2002; 4(1): 1-6.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 Perlmutter G, Apruzzese W. Axillary nerve injuries in contact sports: recommendations for treatment and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1998;26(5): 351-360.

- ↑ Cox C, Kuhn J. Operatice versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocation in the athlete. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2008;7(5): 263-268.

- ↑ McFarland E, Caicedo J, Kim T, Banchasuek P. Axillary nerve injury in anterior shoulder reconstructions: use of a subscapularis muscle- splitting technique and a review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:601-606.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 11.9 Visser C, Coene L, Brand R, Tavy D. The incidence of nerve injury in anterior dislocation of the shoulder and its influence on functional recovery a prospective clinical and emg study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume. 1999; 81-B(4). 679-685.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 Kazemi M. Acute traumatic anterior glenohumeral dislocation complicated by axillary nerve damage: a case report. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 1998;42(3):150-155.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 Safran M. Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, Part 1: Suprascapular nerve and axillary nerve. Am J Sports Med . 2004;32(3):803-819.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 Neal S, Fields K. Peripheral nerve entrapment and injury in the upper extremity. American Family Physician. 2010; 81(2): 147-155.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Vitanzo P, Kenneally B. Diagnosis of isolated axillary neuropathy in athletes:case studies. The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2009; 26:307-311.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 16.9 Miller T. Axillary neuropathy following traumatic dislocation of the shoulder: a case study. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 1998;6(4):184-185.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Manske R, Sumler A, Runge J. Quadrilateral space syndrome. Humen Kinetics-ATTI.2009;14(2):45-47.

- ↑ Mamula C, Erhard R, Piva S. Cervical radiculopathy or parsonage-turner syndrome: differential diagnosis of a patient with neck and upper extremity symptoms. Journal of Orthopaedic Sports Physical Therapy. 2005; 55(10): 659-664.

- ↑ Chernchujit, B. Sulcus Sign Shoulder Dislocation Instability Examination [Video]. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cTDoZo3HPz4. Published May 18, 2008. Accessed November 28, 2010

- ↑ Apprehension Test [Video]. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gLBX8vUnCo0. Published June 2, 2007. Accessed November 28, 2010.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Handoll HHG, Al-Maiyah MA. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for acute anterior shoulder dislocation.Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. 2004;1:1-37.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Deyle G, Nagel K. Prolonged immobilization in abduction and neutral rotation for a first-episode anterior shoulder dislocation. Journal of orthopedic sports physical therapy. 2007; 37(4): 192-198.

- ↑ Gibson K, Growse A, Korda L, Wray E, MacDermid J. The effectiveness of rehabilitation for nonoperative management of shoulder instability: a systematic review. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2004; 17(2): 229-242

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Robinson M, Howes J, Murdoch H, Will E. Graham C. After primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in young patients. The Journal of Bone Surgery. 2006;88(11): 2326-2336.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Mahaffey B, Smith P. Shoulder instability in young athletes. American Family Physician. 1999;59(10): 2773-2782.