Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Down Syndrome (DS) is a genetic, chromosomal condition.[1] Chromosomes are structures found in every cell of the body that contain genetic material and are responsible for determining anything ranging from eye colour to height.[2] Typically, each cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes.[2] However, in individuals with Down syndrome, there is a full or partial extra copy of chromosome 21 in some, or all, cells.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

DS is the most commonly occurring chromosomal variance noted worldwide, with 1 in 1000 births resulting in a child with DS.[1] [3][4] In the UK alone, there are approximately 40,000 people living with Down Syndrome, and 750 are born each year with DS [3]. Birth rates are expected to stay the same, but the total population of persons with DS is expected to rise in the coming years. This is mainly due to medical advancements which have increased life expectancy from age 9 in 1929,[5] to 60 years of age today.[6] With this increase in the number and age of this population, there will be a larger demand on health services, such as physiotherapy, and increased challenges for families to overcome.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Though there are many similarities across the DS population, there is great variation in the syndrome. There are three types of DS: Trisomy 21 (95%), Translocation (3%-4%) and Mosaicism (1%).[7] Whichever the type, persons with DS typically have poorer overall health at a young age and exhibit a greater loss of health, mobility, and increased secondary complications as they age compared to their non-DS counterparts.[8][9] As a result, persons with DS and their families frequently access a range of health services, including physiotherapy.

Physical Characteristics[edit | edit source]

- Growth failure

- Hypotonia

- Ligamentous laxity

- Flat posterior aspect of the head

- Broad flat face

- Slanting eyes

- Epicanthic eyefold

- Short nose

- Small and arched palate

- Big wrinkled tongue

- Dental anomalies

- Short and broad hands

- Special skin ridge patterns

- Unilateral/bilateral absence of one rib

- Congenital heart disease

- Intestinal blockage

- Enlarged colon

- Umbilical hernia

- Pelvis anomalies

- Diminished muscle tone

- Big toes widely spread

Medical conditions[edit | edit source]

DS is not a medical condition, but a common variation in the human form. There are, however, many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include:

- learning difficulties

- poor cardiac health

- thyroid dysfunction

- diabetes

- obesity

- digestive problems

- low bone density

- hearing and vision loss

- dementia and Alzheimer's Disease

- depression

- leukaemia

Developmental Milestones and Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

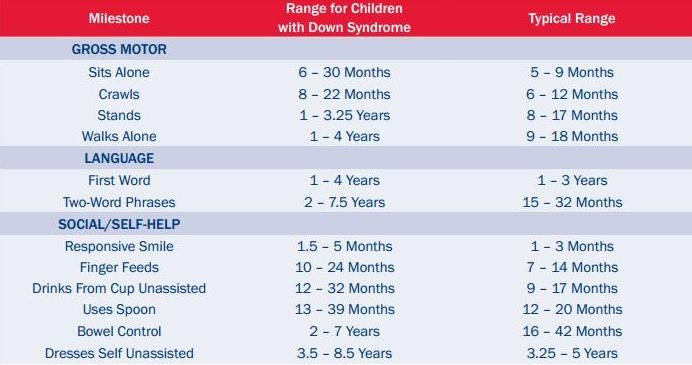

Children with Down Syndrome (DS) will generally achieve the same basic motor skills necessary for everyday living and personal independence. However, it may be at a later age and with less refinement compared to those without DS.[10] Some adjusted milestones for DS are listed in the table below:

It is common for children with DS to be delayed in reaching common milestones such as sitting independently, standing and walking. One of the contributing factors to the delay of these specific milestones is poor balance. Balance challenges often follow a child into their teen years and sometimes into adulthood.[11] Impaired balance may also impact the development of other motor abilities and cognitive development. Being able to maintain balance allows for exploration, social interaction and overall freedom.[12]

Some causes of balance difficulties are:

- ligament laxity

- low muscle tone

- slow reaction times/speed of movement

- differences in brain size: a smaller cerebellum impacts function, limits balance reflexes, and causes blurry vision when completing tasks at high speed. Other parts of the brain can also smaller, creating issues with voluntary activities, walking technique and coordination.

- poor postural control[12][13][14]

Another contributing factor to delayed milestones and a common challenge for individuals with DS is decreased strength.

During childhood, children with DS do not experience the same amount of muscle growth or strength increase as their peers without DS.[15] Individuals with DS typically have 40-50% less strength.[16] Decreased strength can impact activities of daily living, such as walking upstairs, getting out of a seat etc, but it can also lead to:

- increased wear and tear on joints

- higher risk of falls

- elevated level of fatigue

- delayed developmental milestones

- increased risk of osteoporosis[17]

It can also contribute to reduced balance due to weakness of the stability muscles.[17]

Optionally, learn more about Down Syndrome Developmental Milestones and Physical Activity on this page.

Sensation[edit | edit source]

In addition to the other challenges facing people with DS, they can also experience sensory issues.[18] Being unable to process sensory information from the environment (i.e. sensory integration) can be both frustrating and challenging, and often leads to inappropriate behaviour as a response.[19] When sensory feedback is limited, it can impact progress in other areas such as motor development.[18] Sensory difficulties can impact a child’s behaviour and the way they interact with people and objects around them.[19]

Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing[edit | edit source]

It is not uncommon for individuals with DS to experience challenges with emotional behaviours and mental health. Children with DS may have difficulties with communication skills, problem-solving abilities, inattentiveness and hyperactive behaviours. Adolescents may be susceptible to social withdrawal, reduced coping skills, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviours and sleep difficulties. Adults with DS may have similar experiences as adolescents, with further complications of dementia and Alzheimer's later in life [21].

Physiotherapy Management and the Role of the Multidisciplinary Team[edit | edit source]

All members of the multidisciplinary team can play a major role in supporting individuals with DS by adopting a holistic approach to their diverse needs.[22]

Physiotherapists provide tailored interventions to improve physical abilities, strength, and balance, while occupational therapists focus on enhancing daily living skills, fine motor control, and sensory processing. Speech and language therapists help individuals with DS develop effective communication skills and address feeding and swallowing challenges. Psychologists support emotional and cognitive well-being, helping individuals and their families cope with challenges and develop strategies for long-term success.

Effective physiotherapy management of DS typically involves a combination of sensory integration therapy, neurodevelopment treatment, perceptual-motor therapy and traditional strength and conditioning programmes.[23] Physiotherapists educate individuals and their families and provide input on health promotion and long-term condition management.[24] Interventions are based on the individual’s physical and intellectual needs, as well as his or her personal strengths and limitations.[25] Below are some examples of interventions for children with Down syndrome.

- Tummy time

- Neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT)

- Sensory integration therapy (SIT)

- Perceptual-motor therapy (PMT)

- Two-wheeled bicycle training

- Therapeutic horseback riding (hippotherapy)

- Treadmill training

- Balance training

- Strength training

- Physical activity

As many treatments often require on-going maintenance, the team should encourage family members to support and implement home treatment plans in an attempt to encourage self-management.[26] By fostering strong communication among the team members and families, the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team can make a lasting impact on the lives of individuals with DS, helping them achieve their full potential and lead more independent lives.

Resources[edit | edit source]

The following “Ted Talk” presented by Karen Gaffney, a person with Down Syndrome, explores numerous contemporary thoughts surrounding DS and challenges society's preconceptions of people with DS.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 National Down Syndrome Society. What is down syndrome. London: NDSS. https://www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/ (accessed 09 March 2022).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Human Genome Research Institute. Chromosome. Available from https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Chromosome (accessed 9 March 2022).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Learning Disability Today. Spotlight on: Down Syndrome. Available from https://www.learningdisabilitytoday.co.uk/spotlight-on-downs-syndrome (accessed 09 March 2022).

- ↑ Windsperger K, Hoehl S. Development of Down Syndrome Research Over the Last Decades–What Healthcare and Education Professionals Need to Know. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021 Dec 14;12:749046.

- ↑ Carr J, Collins S. 50 years with Down syndrome: A longitudinal study. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018 Sep;31(5):743-750.

- ↑ Zhu J, Hasle H, Correa A, Schendel D, Friedmant J, Olsen J, Ramussen S. Survival among people with down syndrome. Genetics in Medicine 2013;15:64-69. https://www.nature.com/articles/gim201293 (accessed 12 March 2018).

- ↑ Pueschel SM, editor. A parent's guide to Down syndrome: Toward a brighter future. Brookes Pub; 2001.

- ↑ British Institute of Learning Disabilities. Supporting older people with learning disabilities. https://www.ndti.org.uk/uploads/files/9354_Supporting_Older_People_ST3.pdf (accessed 18 March 2018).

- ↑ Cruzado D, Vargas, A. Improving adherence physical activity with a smartphone application based on adults with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1173. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1173 (accessed 11 March 2018).

- ↑ Kim H, Kim S, Kim J, Jeon H, Jung D. Motor and cognitive developmental profiles in children with down syndrome. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 2017;41:97-103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5344833/ (accessed 21 March 2018).

- ↑ Georgescu M, Cernea M, Balan V. Postural control in down syndrome subjects. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. www.futureacademy.org.uk/files/images/upload/ICPESK%202015%2035_333.pdf (accessed 17 March 2018).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Malak R, Kostiukow A, Wasielewska A, Mojs E, Samborski W. Delays in motor development in children with down syndrome. Medical Science Monitor 2015;21:1904-1910. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4500597/ (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Costa A. An assessment of optokinetic nystagmus in persons with down syndrome. Experimental Brain Research 2011;8:110-121. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/08/110824142850.htm (accessed17 March 2018).

- ↑ Saied B, Hassan D, Reza B. Postural stability in children with down syndrome. Medicina Sportiva 2014;1:2299-2304. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1510494760/fulltextPDF/6606B032D8C04A9EPQ/1?accountid=12269 (accessed19 March 2018).

- ↑ Cowley P, Ploutz-Snyder L, Baynard T, Heffernan K, Jae S, Hsu S. Physical fitness predicts functional tasks in individuals with Down syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2010;42:388-393.

- ↑ Mercer V, Stemmons V, Cynthia L. Hip abductor and knee extensor muscle strength of children with and without Down’s syndrome. Phys Ther 2001;1318-26.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Merrick J, Ezra E, Josef B, Endel D, Steinberg D, Wientroub S. Musculoskeletal problems in Down syndrome. Israeli J Pediatr Orthop 2000;9:185-192.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 BruniI M.. Fine motor skills for children with Down syndrome. 2nd ed. Bethesda: Woodbine House Inc., 2006.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lashno M. Sensory integration: observations of children with Down syndrome and Autistic spectrum disorders. Disability Solutions 1999;3:31-35.

- ↑ Scott R. Do you know me. 2015. [Picture]. https://psychprofessionals.com.au/sensory-processing-problem/ (accessed 12 April 2018).

- ↑ Van Germeren-Oosterom H, Fekkes M, Buitendijk S, Mohangoo A, Bruil J, Van Wouwe J. Development, problem behaviour, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. Plos One 2011;6:7.

- ↑ CSP. What is physiotherapy. 2018. www.csp.org.uk/your-health/what-physiotherapy (accessed 14 April 2018).

- ↑ Down Syndrome Association. For Families and Carers. https://www.downs-syndrome.org.uk/for-families-and-carers/ (accessed 6 April 2018).

- ↑ CSP. Learning disabilities physiotherapy. Associated of Chartered Physiotherapists for People with Learning Disabilities. www.acppld.csp.org.uk/learning-disabilities-physiotherapy (accessed13 March 2018).

- ↑ National Human Genome Research Institute. Learning about Down syndrome. https://www.genome.gov/19517824/learning-about-down-syndrome/ (accessed 16 March 2018).

- ↑ Middleton J, Kitchen S. Factors affecting the involvement of day centre staff in the delivery of physiotherapy to adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2008:21:227-235. www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00396.x/epdf (accessed 11 March 2018).

![[20]](/images/c/c6/Elizabeth_Stick_Men.jpg)