HIV-related Neuropathy

Top Contributors - Melissa Coetsee, Kim Jackson and Pacifique Dusabeyezu

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that causes progressive failure of the immune system in humans. Despite the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), neuropathies are still a common complication of HIV. The most common type of neuropathy found in PLWH (distal sensory polyneuropathy) is the leading cause of chronic pain in PLWH and is associated with significant morbidity and negatively impacts quality of life.[1][2][3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of HIV-associated neuropathy varies from 1.73% tot 69.4% among people living with HIV (PLWH).[4] This variability could be attributed to the introduction of antiretroviral treatment (ART), with its benefits and varying adverse effects with evolving drug-combinations. Diagnostic criteria and geographical region also influence the prevalence of HIV-associated neuropathy.[5] The estimated pooled frequency of distal sensory polyneuropathy (DSPN) in Africa, prior to ART, was 27%. This increased to 52% in the post-ART era, and was mainly attributed to the widespread use of Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) - like Stavudine.[5] In a large ongoing study, it has been discovered that 57% of individuals with HIV have distal symmetrical sensory neuropathy, while 38% experience neuropathic pain.[6]

It is however important to note that although the frequency appears to have increased since the introduction of ART, some studies indicate a significant reduction in pain associated with neuropathy - i.e. although patients test positive for neuropathy (based on signs), it is often asymptomatic.[5]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

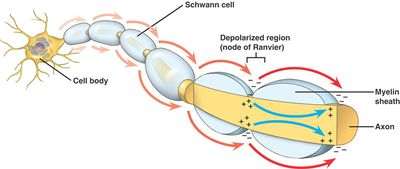

Although other mechanisms may be at play for the less common types of neuropathy (discussed below), HIV-related neuropathy is usually as a result of two distinct pathological processes that lead to distal axonal degeneration, neuronal loss in the dorsal root ganglia and reduced epidermal nerve fibre density[1]:

- Neurotoxic effect of HIV: Indirect neurotoxicity as a result of viral proteins and an inflammatory response to HIV[1]

- Neurotoxic effects of ART: Some ART drugs (NRTIs) associated with an increased incidence of peripheral neuropathy. These include Didanosine, Zalcitabine, Stavudine.[7]Mitochondrial dysfunction is the likely mechanism responsible for this.[8] ART related neuropathy typically develops 5-6 months after initiating ART.[5]

Despite these two distinct pathological processes, the signs and symptoms of each process are not clinically distinguishable.[1]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical presentation varies depending on the type of neuropathy (discussed below), but may include:

- Numbness

- Burning pain

- Altered sensation, including numbness and/or hypersensitivity

- Loss of balance as a result of impaired proprioception

- Diminished or absent lower limb reflexes

- Muscle weakness and muscle wasting (if motor nerves are affected)

Patients may present with functional limitations and chronic painful symptoms. When poorly managed, this can contribute to anxiety, depression and loss of independence.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is based on medical history and clinical examination. A confirmed diagnosis of HIV infection is required, as well as a history regarding NRTI exposure. Signs and symptoms indicative of neuropathy need to be present, with specific patterns and findings guiding the differential diagnosis. If upper motor neuron signs are present (eg. increased tendon reflexes) other conditions need to be considered.

Additional tests (mostly to rule out other conditions) may include:

- Laboratory tests - CD4 count and viral load; vitamin B levels; diabetic screening

- Nerve conduction studies - Not routinely indicated[1]

- Quantitative Sensory Testing - Will reveal abnormalities in cases of peripheral and central nerve disorders

For Distal Sensory Polyneuropathy (DSPN), a clinical diagnostic tool called HIV-associated Neuropathy Tool (CHANT) has been validated for use in Africa, and include the following assessment areas:[9]

- Bilateral feet pain

- Bilateral feet numbness

- Bilateral ankle reflex - Diminished

- Bilateral big toe vibration detection - Diminished

- The following minimum combinations are required to diagnose a patient with PNS: Bilateral feet pain/ reduced great toe vibrations AND Bilateral feet numbness/ reduced ankle reflex

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Also see Neurological Complications of HIV and Neuropathies

- Myelopathy - Including Vacuolar Myelopathy and Pott's Disease

- Opportunistic infections affecting the CNS - TB Meningitis, Neurosyphilis, Toxoplasmosis Encephalitis, Cryptococcal Meningitis

- Other CNS conditions - Stroke, Lymphoma, Aseptic Meningitis

- Vitamin B deficiency - Especially vitamin B12 and B6

- Alcoholic neuropathy

- Diabetic Neuropathy

- Neuropathy related to isolated nerve damage (eg. surgery, compression, traction injury)

- Claudication associated with Peripheral Vascular Disease

- Pain and weakness caused by Central Sensitisation

- Schwannoma

- Morton's Neuroma

- Thyroid dysfunction

- Myopathy or polymyositis

B-Vitamins and HIV[edit | edit source]

B-vitamin deficiencies are prevalent in PLWH and are associated with poor health outcomes. HIV itself causes vitamin-B deficiencies through various mechanisms mostly related to poor absorption.[10]Since vitamin-B6 and B12 have important immune support functions (eg. synthesis of CD4 cells), sufficient amounts of these vitamins could play a protective role in HIV progression.[10] Insufficient vitamin B levels could increase the risk of HIV-related neuropathy as Vitamin B12 is also involved in myelin production.

Isoniazid, a drug used in the treatment of Tuberculosis (TB), can also cause a vitamin B6 deficiency. Since TB is prevalent among PLWH in Africa, this is another mechanisms that could affect vitamin B levels.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Neuropathic pain measures: DN4; LANSS; PainDETECT

- Pain intensity: VAS

- Brief Neuropathy Screening Tool (BPNS): can be used as a screening tool and includes symptom reporting and physical assessment

- Quality of life: WHOQOL-BREF, EQ-5D

- Quantitative Sensory Testing

- Fall Risk Assessment Tool

Types of Neuropathy[edit | edit source]

Neuropathy can occur at all stages of HIV, and various types of neuropathies have been documented. The neuropathies present in PLWH include[5]:

- Distal sensory polyneuropathy (DSPN)

- Inflammatory neuropathies

- Radiculopathies

- Mononeuropathies

1. Distal Sensory Polyneuropathy (DSPN)[edit | edit source]

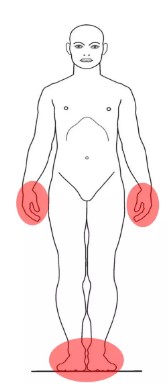

DSPN is the most common type of neuropathy in PLWH.[5]It affects the distal extremities (more commonly the feet, symmetrically) and is caused by axonal damage secondary to dorsal root inflammation. Some patients with DSPN (about 25%) do not experiences any sensory symptoms (asymptomatic DSPN), but for most PLWH it is associated with neuropathic pain .[5][3]

Signs and symptoms include[5][1]:

- Distal symmetric sensory symptoms: burning, stabbing pain and numbness in the soles of the feet/palms of the hands - this ascends symmetrically (stocking-glove distribution)

- Allodynia and Hyperalgesia: sensitivity is most pronounced one the soles and palms

- Reduced or absent ankle reflexes

- Impaired pin prick and vibration sensation

- Impaired proprioception of the affected region

- Weakness and atrophy are rare as only sensory nerves are involved

Risk factors for developing DSPN[5][1]:

- Advanced immunosuppression

- Lower CD4 count and high viral load

- A history of prior TB or alcohol abuse

- ART regime that includes Dideoxynucleoside revers transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), especially Stavudine

- Height and ethnicity may play a role[1]

- Diabetes may exacerbate the risk of neuropathy in PLWH[1]

- Psychosocial factors: depression seems to be associated with greater pain intensity[3]

2. Inflammatory Neuropathies[edit | edit source]

Although uncommon, two forms of autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (IDP) can occur in PLWH[1]:

- Acute IDP (Guillan-Barré syndrome) - Rapidly progressive symptoms, with symmetrical limb weakness and areflexia. Can occur with intact immunity or at seroconversion.[5]

- Chronic IDP - Slower progression, often with a relapsing-remitting pattern; symmetrical limb weakness with areflexia and sensory symptoms. Usually associated with moderately advanced HIV disease.[5]

Both forms are characterised by ascending muscle weakness and areflexia with paraesthesia[1]

3. Radiculopathy[edit | edit source]

Radiculopathy in less common and when present usually affects the lumbosacral nerve roots, mostly caused by Tuberculosis, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) or lymphoma.[1][5]This results in flaccid paraplegia with areflexia and urinary incontinence without upper limb involvement.[5]

4. Mononeuropathy[edit | edit source]

PLWH are at increased risk of mononeuropathies. The most common mononeuropathies are[5]:

- Facial nerve palsy (Bell's palsy): Usually occurs during the early, asymptomatic stages of HIV (at seroconversion). It may present as part of an acute inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy, but this is less common.

- Herpes zoster reactivation: One of the earliest signs of HIV, and affects the thoracic and trigeminal nerve. Complications include myelitis and post herpetic neuralgia.

- Median neuropathy: Leading to carpal tunnel syndrome

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

- HIV infection control - Early diagnosis and treatment with ART

- Drug regime alteration if associated with ART - Avoiding NRTIs; discontinuing Stavudine if symptomatic DSPN develops[1]

- Pain control

- Neuropathic medication (amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin)[5]- Although these medications have proven effectiveness in other neuropathic conditions, they seem to be less effective in HIV-related neuropathy, with studies showing no superiority to placebo in PLWH.[1][8]

- Topical capsaicin patches have shown promise in reducing neuropathic pain in PLWH.[1]

- Complete resolution of pain is not common, but reduction is possible.[1]

- See the page on Neuropathic Pain and Pain in PLWH

- Education - On possible other causes of neuropathy (alcohol, diabetes and vitamin B deficiency)[5]

- Optimisation of contributing factors - Medical management of diabetes, alcohol abuse and vitamin deficiencies (especially vitamin B supplementation)[1][10]

- Treatment of other infections/disorders - in the case of Herpes reactivation, treatment with acyclovir is indicated.[5]Autoimmune inflammatory neuropathies require immunomodulation (acute type) or steroid treatment (chronic type)[5].

Role of Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

- Fall prevention: Even mild forms of neuropathy can result in altered gait and balance which increases the risk of falls.[11]Gait and balance training may reduce fall risk and assistive devices can be prescribed to ensure improved, safer mobilisation. See Falls and Exercise

- Pain management: Neuropathies are often accompanied by neuropathic pain. A recent systematic review recommended exercise (resistance and aerobic) as a potentially effective treatment to reduce neuropathic pain in PLWH[12]. HIV-associated neuropathic pain does however appear to be more refractory to treatment than other neuropathic pain conditions[8]. See Neuropathic Pain

- Resistance and Aerobic Exercises: A recent systematic review concluded that there is sufficient evidence that progressive resistance training and aerobic exercise improves balance, gait, and quality of life in PLWH on ART. [3]See Exercise for PLWH.

- Most of the studies focused on DSPN

- Studies were conducted in a wide range of settings, including African settings (Rwanda and Zimbabwe).[11][13][14]

- Strengthening exercises should focus on lower limb muscle groups (quadriceps, tibialis anterior, hamstrings and gastrocnemius).[13]

- Aerobic exercise should be of moderate intensity and can include brisk walking and cycling.

- The optimal duration of exercise programs appear to be 12 weeks, 2-3 times per week.[3]

- Although exercise has many proven benefits on symptoms and function, it does not seem to alter neuropathy signs in the short term (absent reflexes and vibration sense)[14] - this seems to suggest that exercise works by affecting pain modulation and compensatory strategies, rather than altering pathology. It is still however unsure whether long term results may indicate different findings.

- Neural mobility exercises: Sliding and tensioning techniques may enhance nerve gliding and improve neural mobility. This could translate into reduced pain and improved function by allowing more range of movement[14].

- Psychosocial factors: Assessing and exploring psychosocial factors that contribute to pain and/or non-adherence to medication/interventions

- Foot care: Education on proper footwear, foot hygiene and fall prevention. Since sensation in the feet are altered, daily foot evaluation for skin damage is important.

Summary[edit | edit source]

HIV-associated neuropathy is common among PLWH, despite the introduction of ART. It will likely continue to be a challenge as ART contributes to sensory neuropathies. The lack of effective treatment strategies means that neuropathy continues to have a negative impact on the function and quality of life of PLWH. Screening of neuropathy and thorough assessment of contributing factors should be part of HIV care. Psychosocial factors and medical co-morbidities need to be considered. The research favours non-pharmaceutical interventions and therefore indicates the need for more involvement of rehabilitation team members (physiotherapist, occupational therapists and psychologists) in routine HIV care.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Schütz SG, Robinson-Papp J. HIV-related neuropathy: current perspectives. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care. 2013 Sep 11:243-51.

- ↑ Biraguma J, Rhoda A. Peripheral neuropathy and quality of life of adults living with HIV/AIDS in the Rulindo district of Rwanda. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2012;9(2):88-94.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Amaniti A, Sardeli C, Fyntanidou V, Papakonstantinou P, Dalakakis I, Mylonas A, Sapalidis K, Kosmidis C, Katsaounis A, Giannakidis D, Koulouris C. Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions for HIV-neuropathy pain. A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Medicina. 2019 Nov 28;55(12):762.

- ↑ Yakasai AM, Maharaj S, Danazumi MS. Strength exercise for balance and gait in HIV-associated distal symmetrical polyneuropathy: A randomised controlled trial. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2021;22(1).

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 Howlett WP. Neurological disorders in HIV in Africa: a review. African health sciences. 2019 Aug 20;19(2):1953-77.

- ↑ Gabbai AA, Castelo A, Oliveira AS. HIV peripheral neuropathy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;115:515-29.

- ↑ Hogan C, Wilkins E. Neurological complications in HIV. Clinical Medicine.2011 Dec;11(6):571.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Winias S, Radithia D, Savitri Ernawati D. Neuropathy complication of antiretroviral therapy in HIV/AIDS patients. Oral Diseases. 2020 Sep;26:149-52.

- ↑ Woldeamanuel YW, Kamerman PR, Veliotes DG, Phillips TJ, Asboe D, Boffito M, Rice AS. Development, validation, and field-testing of an instrument for clinical assessment of HIV-associated neuropathy and neuropathic pain in resource-restricted and large population study settings. PLoS One. 2016 Oct 20;11(10):e0164994.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Layden AJ, Finkelstein JL. B-vitamins and HIV/AIDS. Nutrition and HIV: Epidemiological Evidence to Public Health. 2018 May 15:27-87.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Yakasai AM, Maharaj S, Danazumi MS. Strength exercise for balance and gait in HIV-associated distal symmetrical polyneuropathy: A randomised controlled trial. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2021;22(1).

- ↑ Zhang YH, Hu HY, Xiong YC, Peng C, Hu L, Kong YZ, Wang YL, Guo JB, Bi S, Li TS, Ao LJ. Exercise for neuropathic pain: a systematic review and expert consensus. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021 Nov 24;8:756940.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mkandla K, Myezwa H, Musenge E. The effects of progressive-resisted exercises on muscle strength and health-related quality of life in persons with HIV-related poly-neuropathy in Zimbabwe. AIDS care. 2016 May 3;28(5):639-43.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Stewart A, Tumusiime DK, Musenge E, Venter FW. The effects of a physiotherapist-led exercise intervention on peripheral neuropathy among people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in Kigali, Rwanda. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;75(1):1-9.