Kwashiorkor

Original Editors - Kevin Boothe from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kevin Boothe, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

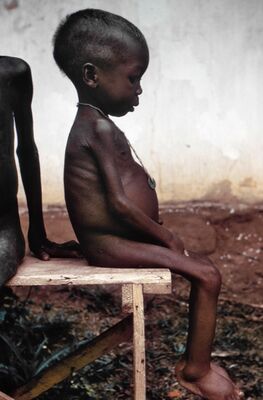

Kwashiorkor is a disease marked by severe protein malnutrition and bilateral extremity swelling. It usually affects infants and children, most often around the age of weaning through age. The disease is seen in very severe cases of starvation and poverty-stricken regions worldwide.

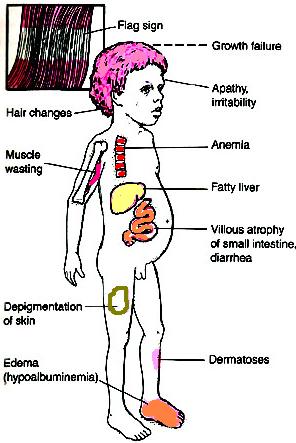

Kwashiorkor is one of two major classifications of severe acute malnutrition. While marasmus is characterised by low weight-for-height, kwashiorkor is diagnosed by bipedal pitting oedema. Other associated signs include pale and brittle hair, skin lesions, lethargy and a fatty liver as well as numerous metabolic anomalies.[1]

In the 1950s, it was recognized as a public health crisis by the World Health Organization. However, there was a delay in its recognition, because most cases of childhood death were reported as being from diseases of the digestive system or infectious etiology. Since then, various relief efforts were aimed at eradicating it[2].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of kwashiorkor is largely unknown, but diets based mainly on maize, cassava, or rice are frequently associated with the disease. It was previously believed to be due to protein deficiency and low levels of antioxidants and aflatoxins. Evidence for these associations exists; however, efforts targeted to replete diets with high-protein and antioxidants have not been successful. Aflatoxin, previously thought to be the etiology of kwashiorkor, is not always associated with the disease in certain populations. Some factors that are consistently associated with the disease include recent weaning, recent infection (particularly measles), and disruptions in childhood (parental death, temporary home environment, poverty).[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Worldwide, the most affected regions include Southeast Asia, Central America, Congo, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, South Africa, and Uganda. Prevalence can vary, but it is seen mostly during times of famine. Rural and farming communities are often affected the hardest. Kwashiorkor is rare in the United States.[1]

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Following symptoms indicate the presence of Kwashiorkor:

- Change in skin and hair colour and texture

- Loss of weight

- Swelling (oedema) of the ankles, feet, and belly

- Irritation

- Compromised immune system

- Failure to gain muscle mass

- Fatigue

- Diarrhoea

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Involves:

- Testing for an enlarged liver or swelling.

- measuring level of sugar and protein (simple blood and urine test).

- Other tests to measure the signs of malnutrition and protein deficiency include:

- Complete blood count

- Urinalysis

- Arterial blood gas

- Potassium blood levels

- Creatinine blood levels[3]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Some complications of kwashiorkor include:

- Hepatomegaly (from the fatty liver)

- Cardiovascular system collapse/hypovolemic shock

- Urinary tract infections

- Abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract eg atrophy of the pancreas with subsequent glucose intolerance, atrophy of the mucosa of the small intestine, lactase deficiency, ileus, bacterial overgrowth (can lead to bacterial septicemia and death).

- Loss of immune function, antioxidant function, subsequent infections, septic shock, and death.

- Endocrinopathies where insulin levels are decreased; growth hormone is increased, but insulin-like growth factor levels are reduced. This leads to insulin intolerance

- Metabolic disturbances and hypothermia

- Impaired cellular functions, including endothelial dysfunction

- Electrolyte abnormalities are commonplace[2]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

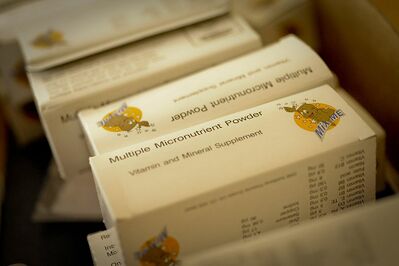

Many pathophysiological steps are involved in the development of protein malnutrition from starvation[1]. Food with more proteins and more calories can treat Kwashiorkor.

- Long term vitamin and mineral supplements are advised by the doctors.

- Calories need to be increased slowly because the patient’s diet lacked any significant nutrition for a long period.

- If there is a delay in the treatment, the child might stay with permanent physical and mental disabilities.

- If the condition is not treated, it might turn fatal[3].

The child's diet must be introduced slowly to limit potential problems associated with the change in cellular and organ function due to inadequate diet. Problems are associated with excessive amounts of fat in the diet leading to bowel and intestinal dysfunction[4] [5]. The main component for medical management, and ensuring that the diet is both cost and resource efficient, is utilizing locally grown products that are cheap, tasteful, easily preserved, and can be incorporated into a variety of food options to provide adequate, additional, and essential nutrients.[6]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

In kwashiorkor, mortality decreases as the age of onset of the disease increases.

- Children may not grow or develop abnormally and may remain stunted.

- There can be serious complications when treatment is not started earlier in the disease course eg shock, coma, and permanent physical and mental disabilities.

- Kwashiorkor can be life-threatening if left untreated[2].

Good Food as Good Medicine[edit | edit source]

Changes in traditional eating patterns have brought about new health threats on the African continent eg an increase in non-communicable diseases. Food is a key component in fighting kwashiorkor. Image: Fried pigeon peas.

- Many indigenous crops are underutilised; these include bambara nuts, pigeon peas, cowpeas, sorghum, finger millets, cocoyam, amaranth, and sweet potato. And people are increasingly relying on new types of food products such as fast foods, processed food and genetically modified products.

- The nutrient density of these crops, as well as algae and edible insects, can be used to diversify diets and to address micro-nutrient deficiencies in poor rural communities.

- Promoting these foods in rural areas could also create opportunities for rural economic development through the development of new value chains. China, Malaysia, India and Vietnam are good examples of countries that derive socio-economic benefits from investment in their traditional food and medical practices.[7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The primary medical intervention is to treat kwashiorkors with an adequate diet. It is more likely for Physical Therapy to play a crucial role in the nursing home setting. Once the patient's diet has been balanced and they are receiving the adequate amount of calories and nutrients, then physical therapy intervention can be applied. If the patient's diet is not adequately met, then the physical therapy intervention will add an increase in energy demands that is not being met, and the intervention will be detrimential instead of beneficial. Physical Therapy intervention should include a general strength and aerobic conditioning program to minimize signs and symptoms associated with kwashiorkor (muscle atrophy and fatigue).

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Protein-energy malnutrition describes a spectrum of diseases that are a result of inadequate nutrients that often affect children living in poor communities of developing countries.[8] Marasmus is the differential diagnosis of kwashiorkor. Marasmus involves inadequate intake of protein and calories, without the presences of edema[9]. The crucial diagnostic features include the percentage of weight loss based on aged norms, and if there is a presence of edema. Using Harvard weight standards, children 60-80% of expected weight for their age are diagnosed with kwashiorkor is edema is present. Children below 60% of expected weight for their age are classified with a diagnosis of marasmic kwashiorkor is edema is present or marasmus if edema is absent.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Fitzpatrick M, Gonzales GB, Rutishauser-Perera A, Briend A. Kwashiorkor–reflections on the ‘revisiting the evidence’series. Field Exchange 65. 2021 May 20:11.Available: https://www.ennonline.net/fex/65/kwashiorkorworkinggroup (accessed 1.9.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Benjamin O, Lappin SL. Kwashiorkor. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 19. Available: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/23961/ (accessed 1.9.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Byjus Kwashiokor Available:https://byjus.com/biology/kwashiorkor/ (accessed 1.9.2021)

- ↑ Kaneshiro NK, Zieve D. Kwashiorkor. Pub Med Health. 2010. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002571. Accessed February 22, 2011.

- ↑ Kaneshiro NK, Zieve D. Kwashiorkor: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Medline Plus. 2010. Available at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001604.htm. Accessed February 22, 2011.

- ↑ Dean RFA. Advances in the treatment of kwashiorkor. British Medical Journal. 1952: 798-801. EBSCOhost. Accessed on March 30, 2011.

- ↑ The Conversation May 2021 African countries must embrace the concept of good food as good medicine Available:https://theconversation.com/african-countries-must-embrace-the-concept-of-good-food-as-good-medicine-156587 (accessed 2.9.2021)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Coward WA, Lunn PG. The biochemistry and physiology of kwashiorkor and marasmus. Medical Bullentin. 1981; 37 (1): 19-24. EBSCOhost. Accessed on March 9, 2011.

- ↑ Shashidhar HR, Grigsby DG. Malnutrition. eMedicine. 2009. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/985140-overview. Accessed March 9th, 2011.