Preeclampsia

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane and Ayodeji Mark-Adewunmi

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pre-eclampsia is a pregnancy-specific multi-system disorder, marked by high blood pressure and often a significant presence of protein in the urine. It typically starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Severe cases may lead to red blood cell breakdown, a low blood platelet count, impaired liver function, kidney dysfunction, swelling, shortness of breath from fluid in the lungs, or visual disturbances. Pre-eclampsia can lead to harmful outcomes for both mother and fetus, including preterm labor. Untreated, it can escalate to seizures, a condition known as eclampsia.

Risk factors for pre-eclampsia include obesity, prior hypertension, advanced age, and diabetes mellitus. It is more common in a woman's first pregnancy or when carrying twins. The condition involves complex mechanisms, including abnormal blood vessel formation in the placenta. Most cases are diagnosed before delivery and can be categorized by the gestational week. Pre-eclampsia often continues into the post-delivery period, known as postpartum pre-eclampsia. Occasionally, it may start after delivery. Traditionally, diagnosis required high blood pressure and protein in the urine, but some definitions now include hypertension with any organ dysfunction.

High blood pressure is defined as greater than 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic on two separate occasions, more than four hours apart, in a woman after twenty weeks of pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia is routinely screened for during prenatal care.

Preeclampsia is one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, causing difficulties in 2-8% of all pregnancies worldwide. Left untreated, women with preeclampsia are at lasrge risk risk for seizures (eclampsia), pulmonary edema, stroke, liver and kidney failure, and death. [1]

- Preeclampsia is a life-threatening cardiovascular disorder associated with pregnancy. Preeclampsia is marked by hypertension and proteinuria at 20 weeks of gestation. The underlying cause is not precisely known but likely heterogenous. Ample research suggests that for some women with preeclampsia, both maternal and placental vascular impairment plays a role in its' evolution and may carry on into the postpartum period.

- Preeclampsia is one of three conditions that constitute the syndrome of ischaemic placental disease, a group of pathologies that also includes placental abruption and intrauterine growth restriction.[2].[3]

Note: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Hypertension in pregnancy should be defined as a hospital systolic blood pressure (SBP) ⩾ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ⩾ 90 mmHg, based on the average of at least two measurements, taken at least 15 min apart, using the same arm. To see Physiopedia's comprehensive page on Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy see here

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Preeclampsia and eclampsia contribute to over 50,000 maternal deaths annually worldwide. The incidence of preeclampsia is linked to ethnicity and race, with the highest prevalence among African-American and Hispanic individuals, accounting for approximately 26% of maternal deaths in these groups.

Numerous risk factors and predeterminants for preeclampsia exist, including having no previous births, pregnancies with multiple gestations, maternal age over 35, use of in-vitro fertilization or other assisted reproductive technologies, and maternal comorbidities such as chronic hypertension, kidney disease, diabetes, thrombophilia, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity with a pre-pregnancy BMI over 30. A family history of the condition, previous experiences of placental abruption or preeclampsia, and intrauterine fetal growth restriction also contribute to the risk.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The exact cause of pre-eclampsia is not definitively known, but it is believed to be linked to various factors. These include abnormal placentation (formation and development of the placenta), immunologic factors, and existing maternal conditions such as hypertension, obesity, or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, especially in those with a history of pre-eclampsia. Dietary factors, like low calcium intake, and environmental factors, such as air pollution, also play a role. Individuals with long-term high blood pressure are 7 to 8 times more at risk.

Physiologically, pre-eclampsia has been associated with changes such as altered interactions between the maternal immune system and the placenta, placental and endothelial cell injury, altered vascular reactivity, oxidative stress, an imbalance of vasoactive substances, reduced intravascular volume, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Evidence suggests that a major predisposing factor for pre-eclampsia in susceptible women is an abnormally implanted placenta, leading to poor uterine and placental perfusion, hypoxia, increased oxidative stress, and the release of anti-angiogenic proteins and inflammatory mediators into the maternal bloodstream. This can result in widespread endothelial dysfunction, which causes hypertension and other symptoms and complications of pre-eclampsia. The abnormal implantation is thought to arise from the maternal immune system's response to the placenta, particularly a lack of established immunological tolerance in pregnancy. Endothelial dysfunction is a key factor in the development of hypertension and the various other symptoms and complications linked to pre-eclampsia.

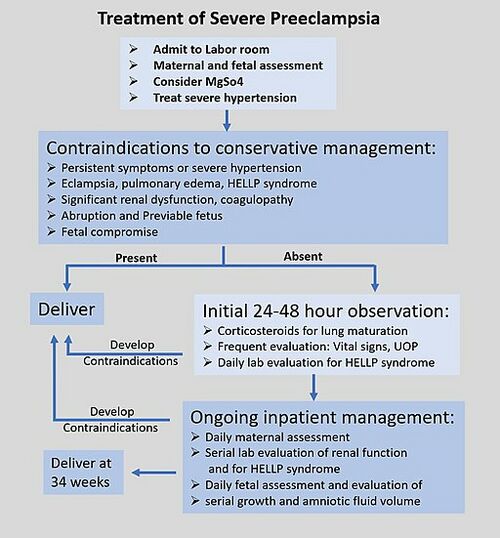

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Preeclampsia may happen at any time during the second half of pregnancy or the first few days after the birth. The signs of preeclampsia are high blood pressure, protein in urine and sudden excessive swelling of the face, hands and feet. Sudden blurred vision is also a symptom. It is also possible to have preeclampsia without having any symptoms at all.

Women seen as high-risk individuals for developing preeclampsia should have administration of low-dose aspirin on a daily basis from early pregnancy as this is currently the most effective way to prevent preeclampsia. For preeclamptic females, specific information and counseling should be provided and appointments with a specialist made. In pregnancies complicated with preeclampsia, closer monitoring and antepartum surveillance ( eg.Doppler ultrasound blood flow study, biophysical profile, non-stress test, and oxytocin challenge test). Early intervention and aggressive therapy should be considered if tests indicate this action. [4]

Maternal Consquences[edit | edit source]

Preeclampsia is associated with:

- An increased relative risk for the development of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in the mother.

- Research shows that women with a history of preeclampsia are 60% more likely to experience ischemic stroke and also have an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke and venous thromboembolism[5].

- Women with a history of preeclampsia have increased an increased risk of cerebral small vessel disease that is highly associated with stroke and dementia. [6]

Neonatal Consequences[edit | edit source]

The neonatal outcomes of preeclampsia identified are:

- Preterm birth, stillbirth, low birth weight (LBW), low Apgar score, intrauterine growth reduction (IUGR), neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.[7]

- Other differences include delayed child physical development and sensorimotor reflex maturation( see Stages of Cognitive Development) , increased body mass index, changes in neuroanatomy and reductions in cognitive function, and hormonal changes.[5]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Women with higher levels of physical activity(PA) during pregnancy seem to have a lower risk of preeclampsia, conversely women with increased levels of sedentary activity were at increased risk. Promotion of PA during pregnancy may be a promising approach for reducing the risk of the disease. However, additional research is needed to confirm the protective effect of PA on preeclampsia risk.[1]

In 2012 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend exercise therapy during pregnancy for women at risk of certain gestational complications, such as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Research suggests that exercise therapy has deleterious effects on uteroplacental perfusion in at-risk pregnancies. Although several studies observed a beneficial effect of exercise therapy on preeclampsia risk, they were not randomized studies and the mechanisms involved in these effects are unknown.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Spracklen CN, Ryckman KK, Triche EW, Saftlas AF. Physical activity during pregnancy and subsequent risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: a case control study. Maternal and child health journal. 2016 Jun;20:1193-202.

- ↑ Parker SE, Werler MM, Gissler M, Tikkanen M, Ananth CV. Placental Abruption and Subsequent Risk of Pre‐eclampsia: A Population‐Based Case–Control Study. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2015 May;29(3):211-9.

- ↑ Opichka MA, Rappelt MW, Gutterman DD, Grobe JL, McIntosh JJ. Vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia. Cells. 2021 Nov 6;10(11):3055.

- ↑ Chang KJ, Seow KM, Chen KH. Preeclampsia: recent advances in predicting, preventing, and managing the maternal and fetal life-threatening condition. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2023 Feb 8;20(4):2994.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Turbeville HR, Sasser JM. Preeclampsia beyond pregnancy: long-term consequences for mother and child. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2020 Jun 1;318(6):F1315-26.

- ↑ Miller EC. Preeclampsia and cerebrovascular disease: the maternal brain at risk. Hypertension. 2019 Jul;74(1):5-13.Available:https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11513 (accessed 5.3.2024)

- ↑ Atamamen TF, Naing NN, Oyetunji JA, Wan-Arfah N. Systematic literature review on the neonatal outcome of preeclampsia. Pan African Medical Journal. 2022 Jan 31;41(1).

- ↑ Genest DS, Falcao S, Gutkowska J, Lavoie JL. Impact of exercise training on preeclampsia: potential preventive mechanisms. Hypertension. 2012 Nov;60(5):1104-9.Available:https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194050 (accessed 6.3.2024)