Tendon Pathophysiology

Original Editor - Michelle Lee

Top Contributors - Admin, Michelle Lee, Kim Jackson, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Wanda van Niekerk, Lucinda hampton and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Overuse can occur in any tendon throughout the body and this usually occurs at the bony attachment, but can also occur in the mid-portion of the tendon, most commonly seen in the Achilles tendon. The cause of tendinopathy has been linked to the repetitive energy storage and release with excessive compression. The quantity, intensity and frequency of this load are unknown, as it can differ from person to person. Two components contribute to this, extrinsic and intrinsic factors (which can include a person's’ biomechanics, body composition, age, gender etc). Previous theories have thought that tendinopathy develops through inflammation via the collagen fibre separation and degeneration through repetitive overload causing microtrauma but studies have shown that in chronic Achilles tendon pain there is an absence of inflammation. The term tendinosis has also been given to patients who have tendon pain. This implies a disorganised healing response is occurring. It has been recommended that these terms should only be used after histopathological examination, which would not seem appropriate for all patient suffering from tendon pain. So this has led to further research and theories. [1]

Current Thinking [edit | edit source]

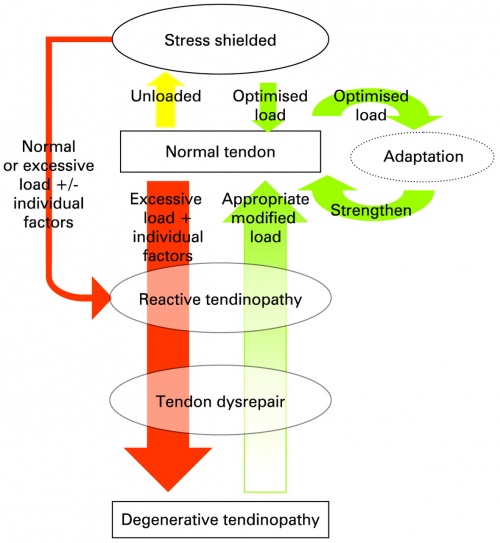

The current term that is recommended to describe this cohort of patients is ‘tendinopathy’. Cook and Purdum have proposed a new strategy when approaching tendon pain, and this is called the tendon continuum. They propose there are 3 stages to this continuum. Being

- Reactive tendinopathy

- Tendon disrepair

- Degenerative tendinopathy.

They suggest that the tendon can move up and down this continuum and this can be achieved through adding or removing load to the tendon especially in the early stages of tendinopathy. They suggest that by reducing the load it may allow the tendon to return to the previous stage on the continuum.[2] However, as Cook and colleagues note in a later study, the relationship between the structure, pain and function of tendons is still not fully understood and this partly contributes to the complexities of managing tendinopathy.[3]

Reactive Tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

A reactive tendon is the 1st stage on the tendon continuum and is a non-inflammatory proliferative response in the cell matrix. This is as a result of compressive or tensile overload. The cells change shape and have more cytoplasmic organelles for increased protein production (proteogycans and collagen). During this process, the collagen integrity is usually maintained although some elongation separation has been shown previously. This phase is a relatively short term adaptation, this process thickens the tendon to reduce stress and increases the stiffness. On imaging the tendon does appear to be thickened and swollen due to the changes in the proteogycans. This can occur after sudden increased stress or direct impact to the tendon. At this stage of tendon has the potential to revert back to the normal tendon.[4]

Tendon Dysrepair[edit | edit source]

The progression of the reactive tendinopathy can occur if the tendon is not offloaded and allowed to regress back to the normal state. During this phase, there is the continuation of increased protein production which has been shown to result in separation of the collagen and disorganisation within the cell matrix. This is the attempt of tendon healing as with the 1st phase but with greater involvement and breakdown physiologically. This is now visible on MRI and ultrasound scans. Also, there may be evidence of increased vascularity and neural ingrowth within the tendon. This phase has been said to be a difficult one to diagnose so history taking is essential, the most accurate method to diagnose this stage is through imaging. This phase of tendinopathy can be developed by frequently overloading the tendon in phase 1 of the continuum. This phase can be developed much more quickly in the older stiffer tendon as there is less flexibility and adaptivity readily available in the tissues. [4]

Degenerative Tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

This is the final stage on the continuum and is suggested that at this stage there is a poor prognosis for the tendon and changes are now irreversible. It has been documented that there areas of cell death, trauma and tenocyte exhaustion and general disorganisation of the cell matrix. On imaging, there are areas of this degeneration scattered throughout the tendon and interspersed with normal sections of tendon and parts of the tendon that are in the dysrepair phase. The tendon can be thickened and present with nodular sections on palpations. Clinically this tendon is present in the older individual who has had ongoing problems with tendinopathy, or the younger individual who has continued to overload the tendon.[4]

Risk Factors [edit | edit source]

From our recent tendinopathy course, the participants were asked to do a literature search to identify the risk factors linked with developing tendinopathy. Here are some of the risk factors they found with references:

- Hormone Replacement Therapy [5]

- Contraceptive medication [6]

- Diabetes [7]

- Obesity [8]

- High adiposity in lower limb tendinopthies [9]

- Use of Fluroquinolones [10][11]

- Lack of range of movement [12]

- Inflexibility[13][14]

- Strength imbalance[15][16]

- Poor vascularity [17]

- Blood Type O [18]

- Altered lower limb biomechanics [19]

- Low temperature training [20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Maffulli N, Sharma P, Luscombe KL. Achilles tendinopathy: aetiology and management. Journal of The Royal Society of medicine 2004;97:472–476

- ↑ Khan K 2007. New Laboratory Insights into the pathogenesis in tendinopathy

- ↑ Cook JL, Rio E, Purdam CR, Docking SI. Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: what is its merit in clinical practice and research? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50:1187-91.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009;43:409–416

- ↑ Holmes GB, Lin J. Etiological Facors Associated with Symptomatic Achilles Tendinopathy. Foot and Ankle International 2006; 27: 952-959

- ↑ Holmes GB, Lin J. Etiologic Factors Associated with Symptomatic Achilles Tendinopathy. Foot and Ankle International 2006. 27:952-959

- ↑ Miranda H, Viikari-Juntur E, Heistaro S, Heliovaara M, Riihimaki H. A population study on differences in the determinants of a specific shoulder disorder versus nonspecific shoulder pain without clinical findings. American Journal Epidemiology 2005; 161(9):847-55

- ↑ van der Worp H, van Ark M, Roerink S, Pepping GJ, van der Akker-Scheek I, Zwerver J. Risk Factors for Patella Tendinopathy: a systematic review of the litrature 2001; 45(5):446-52

- ↑ Gaida JE, Ashes MC, Bass SL, Cook JL. Is adiposity an under-recognized risk factor for tendinopathy? systematic review. Arthitis Care and Research 2009; 61(6): 840-849

- ↑ Van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MCJM, Herings RMC, Leufkens HGM, Stricker BHCh. Flouroquinolones and risk factors Achilles tendon disorders: case-control study. BMJ 2002; 324

- ↑ Kim GK. The Risk of Fluoroquinolone-induced Tendinopathy and Tendon Rupture - What Does the Clinician Need to Know? Journal of clinical Aesthetic Dermatology 2010; 3(4): 49-54

- ↑ Malliaras P, Cook JL, Kent P. Reduced ankle dorsiflexion range may increase the risk of patellar tendon injury among volleyball players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2006; 9(4): 304-9

- ↑ van der Worp H, van Ark M, Roerink S, Pepping GJ, van der Akker-Scheek I, Zwerver J. Risk Factors for Patella Tendinopathy: a systematic review of the litrature 2001; 45(5):446-52

- ↑ Malliaras P, Cook JL, Kent P. Reduced ankle dorsiflexion range may increase the risk of patellar tendon injury among volleyball players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2006; 9(4): 304-9

- ↑ Malliaras P, Cook JL, Kent P. Reduced ankle dorsiflexion range may increase the risk of patellar tendon injury among volleyball players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2006; 9(4): 304-9

- ↑ Hui L, William E, Garrett B, Claude T, Moorman B, Bing Y. Injury rate, mechanism and risk factors of hamstring strain injuries in sports: A review of the literature. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2012; 1(2): 92-101

- ↑ Kader D, Saxena A, Movin T, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2002; 36:239-249

- ↑ Lee DH, Lee HD, Yoon SH. Relationship of ABO Blood Type on Rotator Cuff Tears. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2015; 7(11): 1137-41

- ↑ van der Worp H, van Ark M, Roerink S, Pepping GJ, van den Akker-Scheek I, Zwerver J. Risk Factors for Patella Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review of the Literature. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011

- ↑ Milgrom C, Finestone A, Zin D, Mandel D, Novack V. Cold Weather Training: A risk factor for achilles paratendinitis among recruits. Foot and Ankle International 2003; 24(5): 398-401