Clavicular Fracture

Original Editor - Sofie Van Cutsem

Top Contributors - Elvira Muhic, Sofie Van Cutsem, Manisha Shrestha, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Nupur Smit Shah, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Tony Lowe, Naomi O'Reilly and Karen Wilson

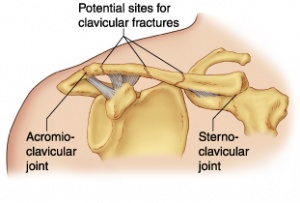

Clinical Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The clavicle is located subcutaneously between the sternum and the scapula, and it connects the arm to the body.[1]

The clavicle is the first bone in the human body to begin intramembranous ossification directly from mesenchyme during the fifth week of fetal life. Similar to all long bones, the clavicle has both a medial and lateral epiphysis but it lacks a well-defined medullary cavity. The growth plates of the medial and lateral clavicular epiphyses do not fuse until the age of 25 years. Peculiar among long bones is the clavicle’s S-shaped double curve, which is convex medially and concave laterally. This contouring allows the clavicle to serve as a strut for the upper extremity, while also protecting and allowing the passage of the axillary vessels and brachial plexus medially.[2]

Clavicle Fracture[edit | edit source]

A clavicle fracture is also known as a broken collarbone.[1] Clavicle fractures are very common injuries in adults (2–5%) and children (10–15%) and represent the 44–66% of all shoulder fractures. It is the most common fracture of childhood. A fall onto the lateral shoulder most frequently causes a clavicle fracture. Radiographs confirm the diagnosis and aid in further evaluation and treatment. While most clavicle fractures are treated conservatively, severely displaced or comminuted fractures may require surgical fixation[3].

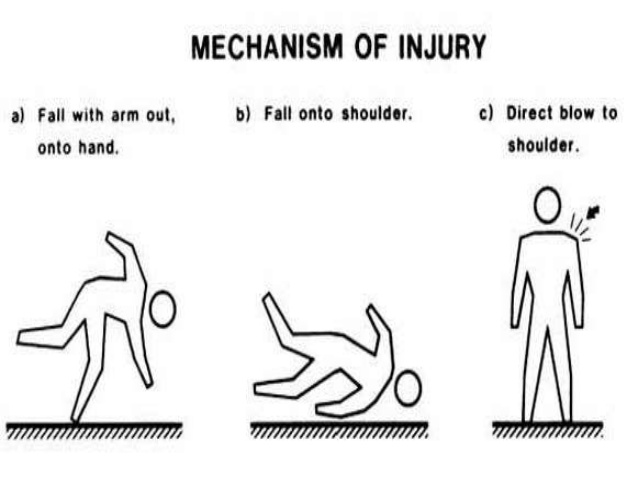

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Younger individuals often sustain these injuries by way of moderate to high-energy mechanisms such as motor vehicle accidents or sports injuries, whereas elderly individuals are more likely to sustain injuries because of the sequela of a low-energy fall.

Although a fall onto an outstretched hand was traditionally considered the common mechanism, it has been found that the clavicle most often fails in direct compression from a force applied directly to the shoulder.[2] About 87% of reported cases, a clavicle fracture results from a fall directly onto the lateral shoulder.[3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Clavicle fractures represent 2% to 10% of all fractures. Clavicle fractures[3]

- Affect 1 in 1000 people per year

- Are the most common fractures during childhood

- Approximately two-thirds of all clavicle fractures occurring in males.

- There is a bimodal distribution of clavicle fractures, with the 2 peaks being men younger than 25 (sports injuries) and patients older than 55 years of age (falls).

- The middle third of the clavicle is fractured in 69% of cases following the distal third in 28% of cases, and the proximal third in 3% of cases.[3]

- Comprise up to 10% of all sport-related fractures and have the third-longest return time to sport with as many as 20% of athletes with such injuries failing to return to sport.[4]

The clavicle is the only osseous link between the upper extremity and the trunk. Due to its superficial subcutaneous location and the numerous ligamentous and muscular forces applied to it, the clavicle is easily fractured. Because the midshaft of the clavicle is the thinnest segment and does not contain ligamentous attachments, it is the most easily fractured location.[3]

Classification[edit | edit source]

Fractures of the clavicle is typically described using the Allman classification system, dividing the clavicle into 3 groups based on location which was later revised by Neer(in which Group II was further classified into 3 types).[3]

Group I: Fractures of the middle third or midshaft fractures (the most common site),

Group II: Fractures of the distal or lateral third. A common site for non-union.

Group III: Fractures of the proximal or medial third.

Robinson’s classification was more specific for different fracture patterns in the middle third, while Craig’s classification was more specific for fractures of the lateral third.[5]

History and Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

The patient may appear with the following signs and symptoms:

- A patient may cradle the injured extremity with the uninjured arm.

- A patient may report a snapping or cracking sound when the injury occurs.

- The shoulder may appear shortened relative to the opposite side and may droop.

- Swelling, ecchymosis, and tenderness may be noted over the clavicle.

- Abrasion over the clavicle may be noted, suggesting that the fracture was from a direct mechanism.

- Crepitus from the fracture ends rubbing against each other may be noted with gentle manipulation.

- Difficulty breathing or diminished breath sounds on the affected side may indicate a pulmonary injury, such as a pneumothorax.

- Palpation of the scapula and ribs may reveal a concomitant injury.

- Tenting and blanching of the skin at the fracture site may indicate an impending open fracture, which most often requires surgical stabilization.

- Nonuse of the arm on the affected side is a neonatal presentation.

- Associated distal nerve dysfunction indicates a brachial plexus injury.

- Decreased pulses may indicate a subclavian artery injury.

- Venous stasis, discoloration, and swelling indicate a subclavian venous injury.[6]

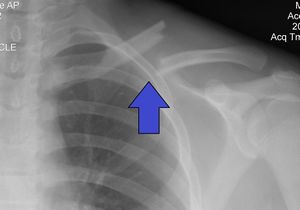

Diagnostic Procedures and Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnose can often be made by a client's history and physical examination.[7]

The differential diagnosis of a clavicle fracture includes acromioclavicular joint injury, rib fracture, scapular fracture, shoulder dislocation, rotator cuff injury, and sternoclavicular joint injury.

Possible complications of clavicle fractures must also be fully evaluated, including pneumothorax, brachial plexus injury, and subclavian vessel injury.[3]

Laboratory studies are ordered in clavicle fractures according to the severity of trauma. With a suspected vascular injury, obtain a complete blood count (CBC) to check the hemoglobin and hematocrit values. If a pulmonary injury is suspected or identified, perform an arterial blood gas (ABG) test and obtain an expiration posteroanterior (PA) chest film. Other imaging studies that can be used in the assessment of a clavicle fracture include the following:

- Radiography of the clavicle and shoulder

- Computed tomography (CT) scanning with 3-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction

- Arteriography

- Ultrasonography[6]

Management[edit | edit source]

Clavicle fracture is management either surgically or conservatively based upon various factors including the location (mid-shaft, distal, proximal), nature (displaced, undisplaced, comminuted) of the fracture, open VS closed injury, age, and neurovascular compromises.[4]

Historically, the management of clavicle fractures has been through conservative management with sling immobilization and subsequent rehabilitation. This continues to provide satisfactory results for undisplaced fractures but conservative management of displaced mid-shaft clavicle fractures results in increased rates of re-injury, increased return times to sport and suboptimal shoulder function, secondary to clavicular mal-union and shortening, with resultant thoracoscapular dyskinesia. Similarly, conservative management of displaced lateral fractures in the athletic patient has been shown to result in high rates of non-union and subsequent impairment of shoulder function.

So for the athletic individual, operative intervention is routinely performed for displaced lateral fractures and is recommended for mid-shaft fractures that are completely displaced, shortened >2 cm or comminuted.[4]

Surgical Treatment[edit | edit source]

The chief goal of this treatment is to achieve a healed clavicular strut in a normal anatomical position as possible.

Indications for operative treatment of clavicular fractures are;[8]

- Severe displacement caused by comminution with resultant angulation and tenting of the skin severe enough to threaten its integrity and that fails to respond to closed reduction.

- Symptomatic non-union like shoulder girdle dysfunction neurovascular compromise.

- Neurovascular injury or compromise that is progressive or that fails to revere after the closed reduction of the fracture.

- Open fracture.

- Type II distal clavicular fracture (displaced).

- Multiple traumas, when mobility of the patients is desirable and closed methods of immobilization are impractical or possible.

- Floating shoulder.

- Inability to tolerate closed immobilization such as neurological problems of Parkinsonism, seizure disorders.

- Cosmetic reasons.

- Relative indications include shortening of more than 15 to 20mm and displacement more than the width of the clavicle.

Surgical procedure includes:[9]

- Internal fixation with plates and screws.( most common)

- Intramedullary fixation.

Rehabilitation:[edit | edit source]

Helps to improve and restore the function of the shoulder for activities of daily living, vocational, and sports activities.

Rehabilitation After Postoperative treatment of clavicle fracture.[edit | edit source]

Primary open reduction and internal fixation with plate ( locking compression plate) and screws of middle third clavicle fractures provides a more rigid fixation and allow immediate post-surgical mobilzation.[8]

Rehabilitation protocol: Day one to one week: Limb is immobilized in a sling with shoulder held in adduction and internal rotation. Elbow is maintained at 90° of flexion with no range of motion at shoulder.

- i. At two weeks: After suture removal gentle pendulum exercises to the shoulder in the sling as pain permits is allowed.

- ii. At four to six weeks: At the end of 6 weeks gentle active range of motion of the shoulder is allowed. Abduction is limited to 80°.

- At six to eight weeks: Active to active – assistive range of motion in all planes is allowed.

At eight to 12 weeks: Isometric and isotonic exercises are prescribed to the shoulder girdle muscles.

Rehabilitation for conservative management of clavicle fracture.[edit | edit source]

Patients are immobilized in a sling or figure-of-eight brace until the clinical union is achieved. This typically occurs by 6 to 12 weeks in adults and 3 to 6 weeks in children. Patients should perform a range of motion and strengthen exercises under the care of a physical therapist once immobilization is no longer necessary. Patients typically may resume full daily activity approximately 6 weeks after injury. Requiring 2 to 4 months of rehabilitation, return to full contact sports requires the athlete should demonstrate radiographic evidence of bony healing, no tenderness to palpation, a full range of motion, and normal shoulder strength.[3] This 13-minute video is good viewing

Advice for a New Injury and 0-3 Weeks Post-Injury[edit | edit source]

- Cold packs: A cold pack (ice pack or frozen peas wrapped in a damp towel) can provide short term pain relief. Apply this to the sore area for up to 15 minutes, every few hours ensuring the ice is never in direct contact with the skin.

- Rest: Try to rest your shoulder for the first 24-72 hours. However, it is important to maintain movement. Gently move your shoulder following the exercises shown. These should not cause too much pain. This will ensure your shoulder does not become stiff and it will help the healing process.

- Wear the sling during the day, except for exercises and personal hygiene. Clients choice to wear at night or not.

- Client starts Finger and wrist flexion and extension, Elbow Bend to Straighten, Forearm Rotations and Postural awareness instructions and training given

- Do not lift your elbow above shoulder height as this may be painful.

Therapy/Advice 3-6 Weeks Post-Injury[edit | edit source]

- Try not to use the sling.

- Begin normal light activities with the arm and shoulder.

- Increase movement: Active assisted Shoulder flexion 4 to 5 times daily, Active assisted External rotation 4 to 5 times daily.

- Avoid heavy lifting for the full 6 weeks.

Therapy/Advice 6 Weeks Post-Injury[edit | edit source]

- Start active range of movement shoulder exercises ie Forward flexion, abduction and external rotation

- Perform these exercises 10 times each.

- Only go as far as you can naturally, without doing any trick movements to try and get any further.

- The movement should increase over time and should not be forced.[11]

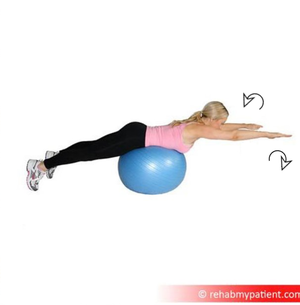

For people returning to sports or heavy work

Weeks 12 And Beyond[edit | edit source]

- Start a more aggressive strengthening program as tolerated.

- Increase the intensity of strength and functional training for gradual return to activities and sports.

- Return to specific sports is determined by the physical therapist through functional testing specific to the patient’s demands

- completion of Sports Test for specific initial return to sports and progressive sport-specific training[12]

Return to Sports[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Patients with clavicular fractures are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, emergency department physician, primary care provider, nurse practitioner and a physical therapist. The majority of clavicle fractures are managed with conservative care. This includes physiotherapy.

Immediate orthopedic consultation should be obtained for patients with neurovascular compromise, open fractures, tenting of the skin, or any break in the skin near the fracture.

The healing of the fracture may take 8-12 weeks and most patients have a good outcome. However, a few patients may have chronic pain and limited range of motion of the shoulder.[3]

An early mobilization rehab protocol can be safely recommended for both types of conditions (acute and non-union post-operative cases).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Clavicle Fracture (Broken Collarbone). www.orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00072

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Paladini, P et al. “Treatment of Clavicle Fractures.” Translational Medicine @ UniSa 2 (2012)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Bentley TP, Journey JD. Clavicle Fractures. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 May 6. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507892/ (last accessed 22.12.2019)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Robertson GA, Wood AM. Return to sport following clavicle fractures: a systematic review. British medical bulletin. 2016 Sep 1;119(1).

- ↑ O’Neill BJ, Hirpara KM, O’Briain D, McGarr C, Kaar TK. Clavicle fractures: a comparison of five classification systems and their relationship to treatment outcomes. International orthopaedics. 2011 Jun 1;35(6):909-14.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Medscape. Kleinhenz BP, Young CC, Clavicle Fractures. www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/92429-overview#showall

- ↑ M. Pecci, J. Kreher, MD, Boston university, Clavicle fractures, jan. 2008. Level of evidence: 1 Grade of recommendation: B

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Reddy YT, Reddy SS, Reddy V, Vadlamani KV, Suresh M. Operative treatment of clavicular fractures: a prospective study. JOURNAL OF EVOLUTION OF MEDICAL AND DENTAL SCIENCES-JEMDS. 2015 Sep 24;4(77):13394-410.

- ↑ Fanter NJ, Kenny RM, Baker III CL, Baker Jr CL. Surgical treatment of clavicle fractures in the adolescent athlete. Sports health. 2015 Mar;7(2):137-41.

- ↑ Bob and Brad Clavicle fracture Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uUT2Ozin5o&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 22.12.2019)

- ↑ Virtual fracture clinic. Clavicle Fracture. Available from: https://www.fracturecare.co.uk/care-plans/shoulder/mid-shaft-clavicle-fracture/clavicle-with-fu-6-52/ (last accessed 22.12.2019)

- ↑ Stone clinic Broken collar bone Available from: https://www.stoneclinic.com/broken-collarbone-rehab-protocol (last accessed 22.12.2019)