Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! 21/11/2020

Original Editors - Wouter Claesen

Top Contributors - Abbey Wright, Heleen Van Cleynenbreugel, Beverly Klinger, Kim Jackson, Darrell Blommaert, Admin, Wouter Claesen, Michelle Lee, Daphne Jackson, Leana Louw, 127.0.0.1, Fasuba Ayobami, Celine De Wolf, Wanda van Niekerk, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas and Naomi O'Reilly

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

An injury to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee can be caused by varus stress, lateral rotation of the knee when weight-bearing or by repeated varus stress . An injury of the lateral collateral ligament most often occurs from a varus force or by twisting the knee. Such an injury occurs in sports with a lot of quick changes in direction or with violent collisions. Examples are soccer, basketball, skiing, football or hockey.

The LCL can be sprained (grade I), partially ruptured (grade II) or completely ruptured (grade III) .[1]

Additional damage of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and medial knee structures is possible when the lateral knee structures are injured [1][2].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

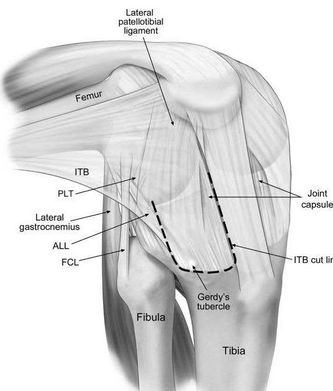

The LCL is a structure of the arcuate ligament complex, together with the biceps femoris tendon, popliteus muscle and tendon, popliteal meniscal and popliteal fibular ligaments, oblique popliteal, arcuate and fabellofibular ligaments and lateral gastrocnemius muscle[2][3].

The LCL is a strong connection between the lateral epicondyle of the femur and the head of the fibula, with the function to resist varus stress on the knee and tibial external rotation and thus a stabilizer of the knee. When the knee is flexed to more than 30°, the LCL is loose. The ligament is strained when the knee is in extension.[1]

See LCL anatomy for more detailed anatomy.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Injuries to the lateral and medial collateral ligaments are common, however, MCL injuries occur more often than the LCL injuries.

25% of patients in the United States with an acute knee injury in emergency rooms have a collateral ligament injury. Adults aged between 20-34 and 55-65 years old have the highest incidence.

LCL (and MCL) injuries occur equally for men and women.

These injuries are normally successfully treated with conservative methods.

Surgery can be necessary in extreme cases, however, there is a good prognosis.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acute[1][edit | edit source]

- Knee swelling

- Pain

- Lateral joint line pain

- Pain with varus stress test

- Increased varus movement with varus stress testing

- Reduced ROM

- Difficulty to fully weight bear

- Weakness of the quadriceps and inability to straight leg raise.

- Instability and giving way

Sub-Acute[edit | edit source]

- Lateral knee pain

- Stiffness end of range flexion or extension

- Weakness of effected leg

- Possible further giving way

Persistent/Chronic[3][edit | edit source]

- Unspecific knee pain

- Significant weakness in whole of kinetic chain

- Potential giving way

- Mal-adaptive movement patterns

Differential Diagnosis[2][edit | edit source]

- Injury at the posterolateral corner

- PCL tear

- ACL tear

- Meniscus tear/ injuries

- Popliteus avulsion

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome

- Distal hamstring tendinopathy

The LCL is not connected with the lateral meniscus, so it is not automatically associated with a meniscal tear.

LCL injuries often occur along with other ligament injuries, including ACL, PCL, and MCL, and is frequently seen along with knee dislocations.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis can usually be made following the subjective assessment depending on the mechanism of injury. LCL injury is normally accompanied by ACL or posterolateral corner injury so ensure screening of these are completed see ACL screening.[4]

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

- Observation

- Palpation

- Active range of movement (ROM)

- Muscle testing

- Gait analysis

- Special tests including ligament laxity testing: varus, valgus, anterior/posterior draw, lachmanns

Varus Stress Test video provided by Clinically Relevant

7. Neurological exam (if required)

In objective assessment it may be useful to grade the level of sprain:

Grade I:[edit | edit source]

- Mild tenderness and pain over the lateral collateral ligament

- Usually no swelling

- The varus test in 30° is painful but doesn’t show any laxity (< 5 mm laxity)

Grade II:[edit | edit source]

- Significant tenderness and pain on the lateral collateral ligament and on lateral side of the knee

- Swelling in the area of the ligament

- The varus test is painful and there is laxity in the joint with a clear endpoint. (5 -10mm laxity)

Grade III:[edit | edit source]

- The pain can vary and can be less than in grade II

- Tenderness and pain at the lateral side of the knee and at the injury

- The varus test shows a significant joint laxity (>10mm laxity)

- Subjective instability

- Significant swelling

The peroneal nerve can also be injured which can be identified by a foot drop. of the patient while he is walking or when the patient feels a numbness or weakness in the foot. [5]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management of LCL injuries can be considered in grade I or II sprains.[6]

This approach mainly consists of physiotherapy which is discussed in the following paragraph.

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Grade III sprains are more severe, the anterior cruciate, posterior cruciate ligaments or posterolateral corner may also have become damaged. In this case surgery can be needed to prevent further instability of the knee joint.[7]

The goal of surgical management is to achieve a stable, well-aligned knee with normal biomechanics[8].

Surgical management of LCL injuries normally involves reconstruction of the LCL sometimes using ITB.[9]

Post Operative Rehab[edit | edit source]

Post operative rehabilitation can involve an altered weight-bearing status for the first six weeks. This is likely to be partial weight-bearing but when extensive additional surgery has been undertaken it could be non-weight bearing[6].

A knee immobiliser may also be used to limit valgus/varus stresses on the knee as well as stop the knee flexing during gait.

Early ROM exercises should be encouraged in a non-weight bearing position.

After the initial post-operative phase, normal rehab can start as detailed in the physiotherapy management. It is useful to note that if a meniscal repair is also done deep squats should be avoided for the initial four months.[6]

Physiotherapy Management [edit | edit source]

For general management see: Ligament injury management

As with other ligament injuries such as ACL repairs or ruptures a milestone-based approach can be undertaken, however, normal soft tissue healing timescales should be kept in mind when designing rehab programs[6].

Acute Management[6][edit | edit source]

- POLICE or RICE

- Analgesia

- Oedema (swelling) management

- Bracing in a knee immobiliser or adjustable brace which allows limited flexion but full extension.

- Offloading of the knee as required with crutches

- Early mobilisation of the knee should be encouraged

- Quadriceps activation exercises

- Ensure straight leg raise with no lag

- Electrical stimulation can also prevent the muscles wasting due to immobilisation. [10]

Sub-Acute Management[edit | edit source]

- Full weight-bearing - gait re-education

- Full AROM of knee

- Progression of strength exercises of quadriceps, glutes, gastrocnemius and hamstrings.

- Closed chain strength work

Long-Term Management[edit | edit source]

- Proprioception work

- Plyometric exercises - with focus on reducing excessive varus or external tibial rotation[11].

- High-level strengthening and loading of the whole kinetic chain

- Aerobic conditioning

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

An injury to the lateral collateral ligament of the knee can be caused by varus stress, lateral rotation or by degeneration. Additional damage to the ACL, PCL, posterio-lateral corner and lateral knee structures is possible with an LCL injury. In case of a grade III sprain, surgery may be needed to prevent further instability of the knee joint. Conservative management should always be the initial treatment choice.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ, Godges JJ. Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2010 Apr;40(4):A1-37.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Recondo JA, Salvador E, Villanúa JA, Barrera MC, Gervás C, Alústiza JM. Lateral stabilizing structures of the knee: functional anatomy and injuries assessed with MR imaging. Radiographics. 2000 Oct;20(suppl_1):S91-102.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ricchetti ET, Sennett BJ, Huffman GR. Acute and chronic management of posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. Orthopedics. 2008 May 1;31(5).

- ↑ Hirschmann MT, Zimmermann N, Rychen T, Candrian C, Hudetz D, Lorez LG, Amsler F, Müller W, Friederich NF. Clinical and radiological outcomes after management of traumatic knee dislocation by open single stage complete reconstruction/repair. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2010 Dec 1;11(1):102.

- ↑ Baima J, Krivickas L. Evaluation and treatment of peroneal neuropathy. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Jun 1;1(2):147-53.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Lunden JB, BzDUSEK PJ, Monson JK, Malcomson KW, Laprade RF. Current concepts in the recognition and treatment of posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2010 Aug;40(8):502-16.

- ↑ Pekka Kannus, MD Nonoperative treatment of Grade II and III sprains of the lateral ligament compartment of the knee , Am J Sports Med January 1989 vol. 17 no. 1 83-88

- ↑ Cooper JM, McAndrews PT, LaPrade RF. Posterolateral corner injuries of the knee: anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2006 Dec 1;14(4):213-20.

- ↑ Wang CJ, Chen HS, Huang TW, Yuan LJ. Outcome of surgical reconstruction for posterior cruciate and posterolateral instabilities of the knee. Injury. 2002 Nov 1;33(9):815-21.

- ↑ Dr Pekka Kannus, Markku Järvinen, Nonoperative Treatment of Acute Knee Ligament Injuries, sports medicine, 1990, Volume 9, p244-260 (level of evidence: 3a)

- ↑ Mohamed O, Perry J, Hislop H. Synergy of medial and lateral hamstrings at three positions of tibial rotation during maximum isometric knee flexion. The Knee. 2003 Sep 1;10(3):277-81.