Pregnancy Related Pelvic Pain

Original Editors - Marlies Verbruggen

Top Contributors - Marlies Verbruggen, Nicole Hills, Rotimi Alao, Andeela Hafeez, Lara Lagrange, Vanwymeersch Celine, Kim Jackson, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Evan Thomas and Fasuba Ayobami

[See also Chronic Pelvic Pain]

Description[edit | edit source]

According to the European guidelines of Vleeming and colleagues,[1] “Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ). The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis.”[1]

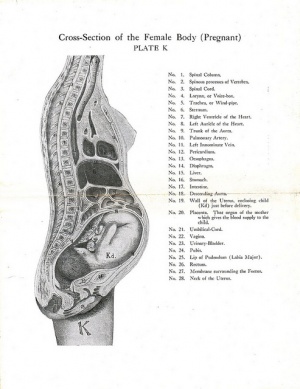

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The pelvis is composed of the sacrum, ilium, ischium and pubis. The pelvic bone consists the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint.

Sacroiliac Joints

The sacroiliac joints allow for the transfer of forces between the spine and the lower extremity.[2] To read more about the function of the sacroiliac joints review: Force and Form Closure

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles have two primary functions in females:[3]

- supports the abdominal viscera (bladder, intestines, uterus) and the rectum

- the mechanism for continence for the urethral, anal and vaginal orifices[3]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Pelvic girdle pain may begin around the 18th week of pregnancy and appears to peak between the 24th and 36th week.[4] Pelvic pain is common during with approximately 50% of women experiencing this pain during pregnancy.[5] 25% of the women who experience pelvic girdle pain report having severe pain and 8% report pain that causes severe disability. and disability.[6]

The etiology of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain has not been established in the literature[7] however, the cause of this pain is believed to be multi-factorial and may be related to hormonal, biomechanical, traumatic, metabolic, genetic and degenerative factors.[8] [9] [10]

Hormonal[edit | edit source]

Women produce increased quantities of the hormone relaxin during their pregnancy. Relaxin increases ligament laxity in the pelvic girdle (and in other parts of the body) in preparation for the labour process. Increased ligament laxity may cause a small increase in the range of motion at the pelvis. If this increase in motion is not complimented by a change in neuromotor control (e.g., muscles around the pelvis act to improve stability), it is possible that pain may occur.[1] However, the link between relaxin and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy has not been well established in the literature.[9][10] Research to date also does not support the idea that an increase in the range of motion at the pelvis causes pain.[1][11] [12]

Biomechanical[edit | edit source]

As pregnancy progresses the gravid uterus increases load on the spine and pelvis. To accommodate for the growth of the uterus the pubic symphysis must soften and the laxity of the ligaments of the pelvis increases. The uterus shifts forward which changes the maternal centre of gravity and the orientation of pelvis.[13] This change in centre of gravity may cause stress or a change in load on the lower back and pelvic girdle.[9][14][10] This change in load can result in compensatory postural changes (e.g., an increase in lumbar lordosis).[9][14][10]

There is also a significant reductions in the strength of the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, pelvic floor, lumbar multifidus and an inadequate coordination of the lumbopelvic muscles is often observed by pregnant women with PGP. When PGP arises in the 2nd and 3rd trimester of pregnancy, abdominal stretching and a shift of body gravity center can possibly cause this muscle impairment. The reduced force closure can lead to neuromuscular compensatory strategies. There are two common compensating strategies, namely the butt-gripping and the chest-gripping strategy. In the butt-gripping strategy,there is an overuse of the posterior gluteal muscles. In the chest-gripping strategy, the external oblique is in overdrive, which means that the external oblique is going to work/contract harder and faster to compensate for the underuse of the transversus abdominis. This leads to an incorrect load transfer between the thorax and the pelvis, which can cause hypertrophy of the external oblique. These strategies, the butt-gripping and chest-gripping strategies, may increase sheared forces in the SIJ, which might cause pain. In response to the pain there are two maladaptive forms of behavior: pain avoidance and pain provocation behavior, this can increase pain and disability.[15][16]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

The risk factors for the development of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain are:

- a previous history of low back pain or pelvic girdle pain.[17][10]

- a previous trauma to the pelvis or back.[17][10]

- physical demanding work (e.g., twisting and bending the back several times per hour per day).[1][5][18][15][19]

- multiparity[20]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The clinical presentation of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain is characterized by a wide variation of symptoms.

Pain

Often, the onset of pain occurs around the 18th week and reaches peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy. The pain can spontaneously disappear within 3 months, but 7-8% of the patients have a persisting, chronic pain.[5][16] Improvement of persistent PGP levels off around 6 months postpartum.[18] More women experience PGP 18 months after delivery as breastfeeding decreased.[21]

Localisation

Pain is often localized deep in the sacral/gluteal region.[1][5] Following the guidelines the pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, mostly surrounding the sacroiliac joints.[18] The localization of pain is deep and can be divided in five groups as mentioned above under ‘etiology and epidemiology’. It is even possible that localization of the pain changes over time.

Nature of pain

Pelvic girdle pain has been described as “stabbing’’ , pain in the lower back as a “dull ache’’ and the pain in the thoracic spine is rather “burning’’. Other pain-descriptions are: shooting pain, feeling of oppression and a sharp twinge.[16]

Intensity of pain: The intensity of pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS) is usually around 50-60 mm.[22][5] The pain may be mild or quite bearable in about half of the cases and very serious in about 25%.[1][5][16]

Changes in the perception and execution of movements

Several women reported a “catching” sensation in their upper leg when they were walking. Patients with PGP also experienced a feeling of paralysis in their legs while they were lifting their leg in extension.[5]

Changes in movement coordination: Women with postpartum PGP have a stronger coupling between pelvic and thoracic rotations during gait. This may be a strategy chosen by the nervous system to cope with motor problems.[5]

Patients, who suffer from pelvic girdle pain, have difficulty during:

- Walking (quickly): Alternated gait pattern (slower walking velocity, waddling type of gait)[1][22][5]

- Sexual intercourse[22][5]

- During sleep: Turning in bed[5][23]

- Housework[5][23]

- Activities with children[5]

- Sitting[23]

- Standing for 30 minutes or longer[23]

- Climbing stairs[23]

- Running (postnatal)[23]

- Individual and socio-economic consequences[18]

- Impaired mother-child interactions[18]

- Weight bearing activities[14]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Women with anterior and posterior pain location have the worst pro.gnosis meanwhile an isolated anterior pain predicts a good prognosis.[18] Breastfeeding is associated with small beneficial effect on the recovery process of the pelvic girdle pain in women with BMI >25 kg/m² (low level of evidence)[24] The recovery rates decreased with increasing levels of pain severity at pregnancy week 30. Women who experienced emotional distress during pregnancy are more likely to report PGP after delivery.[18] [14] Poorer prognosis if women have PGP and low back pain.[18]

Women who exercise regularly (high impact exercise) have low risk to develop[25] PGP.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of pelvic pain in women can be challenging because many symptoms and signs are insensitive and nonspecific. As the first priority, urgent life-threatening conditions (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, ruptured ovarian cyst, ovarian vein thrombosis, placental abruption) , fertility-threatening conditions (e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, endometritis), painful visceral pathologies of the pelvis (urogenital and gastrointestinal), lower-back pain syndromes (e.g. lumbar disc-lesion, rheumatism or sciatica) , bone or soft tissue infections, urinary tract infections, femoral vein thrombosis, rupture of symphysis pubis and bone or soft tissue tumors must be considered.[22][26]

The most common urgent causes of pelvic pain are pelvic inflammatory disease, ruptured ovarian cyst, and appendicitis; however, many other diagnoses in the differential may mimic these conditions, and imaging is often needed. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be the initial imaging test because of its sensitivities across most etiologies and its lack of radiation exposure. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for pelvic inflammatory disease when other etiologies are ruled out, because the presentation is variable and the prevalence is high. Multiple studies have shown that 20 to 50 percent of women presenting with pelvic pain have pelvic inflammatory disease. Adolescents, pregnant and postpartum women require unique considerations.[27]

The differential diagnoses of low back pain and pelvic girdle pain is very similar. PGP is mostly located between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold near the sacroiliac joints, it has possible symphysis dysfunction. Pain is intermittent and may be provoked by daily activities such as walking, sitting or standing. A careful medical history focusing on pain characteristics is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis. The patient should be asked about the location, intensity, radiation, timing, duration, and exacerbating and mitigating factors of the pain. Review of systems, gynecologic, sexual, and social history, in addition to physical examination and an appropriate laboratory test, helps to narrow the differential diagnosis.[15]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

To diagnose a pregnant woman with pelvic pain, symptoms must be distinguished from lumbar pain first. Tests for the sacroiliac joint show good reliability to distinguish low back pain from sacroiliac joint pain. A precise pain location of the provoked pain must be obtained for the test to have enough specificity.[28] Further diagnosis can be reached from signs and symptoms experienced and described by the pregnant women. Common symptoms related to pregnancy-related pelvic pain include:[29][28]

- Difficulty walking (waddling gait)

- Pain on weight bearing on one leg e.g. climbing stairs, dressing

- Pain and/or difficulty in straddle movements e.g. getting in and out of bath; turning in bed

- Clicking or grinding in pelvic area – may be audible or palpable

- Limited and painful hip abduction (though some women have normal or only partly limited abduction)

- Difficulty lying in some positions e.g. supine, side-lying

- Pain during normal activities of daily life

- Pain and difficulty during sexual intercourse

- Difficulty walking (waddling gait), with a diminished endurance capacity for standing, walking and sitting

- Pain: Distribution varies between individuals and includes:

- Lower back

- SPJ

- SIJ(s)

- Groin

- Anterior and posterior thigh

- Posterior lower leg

- Hip/trochanteric region

- Pelvic floor/perineum

If pain is evident in the sacroiliac joint, a combination of tests can be done to further exclude lumbar pain and other syndromes from the SIJ. A combination of the sacral sulcus tenderness test (or palpation of the long dorsal ligaments) and the pointing to the spina iliaca posterior superior (SIPS) test (or pointing to the joint test) have the best predictive value for pelvic pain. Two more sensitive tests are palpation of the symphysis and painful femoral compression, these two tests are also called posterior pelvic pain provocation test. The posterior pelvic pain (PRPP) provocation test and Patrick’s/Faber Test (flexion, abduction and external rotation) show high sensitivity if pain is evident in the SIJ.[28][30][31]

Other diagnostic tests and imaging for PRPP:

- Urinalysis, midstream specimen of urine (MSU).

- High vaginal swab (HVS) for bacteria and endocervical swab.[1]

- Pregnancy test.

- MRI (most suggested imaging modality to evaluate PGP)[15]

- Ultrasonography[15]

- FBC/A full blood count: this is a very common blood test and is used to check a person's general health as well as screening for specific conditions. The number of red cells, white cells and platelets in the blood are checked.

- Urgent ultrasound (if miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy is suspected).

- Laparoscopy[24]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)[32]

Timed up and go test (Fast pace)[33]

10 m timed walk test (Fast pace)[33]

Oswestry Disability Index[18]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The description with what the patient feels is important to know. Like a “catching feeling when walking” is often a sign of posterior pelvic pain, but further test need to be performed to see if it is really a posterior pelvic pain.[34] It is also very important to ask the patient about his pain history. The use of a pain location diagram is strongly recommended, so that we can be sure that the pain is localized in the pelvic area. The patient may also point out the pain location on his or her body.[1][26]

The following tests are recommended for the clinical examination, to make the diagnosis of pelvic girdle pain:

For SIJ pain:

- Posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4)[1][22][35] [36] This is a pain provocation test used to determine the presence of sacroiliac dysfunction. It is used to distinguish between pregnancy-related pelvic pain (PRPP) and low back pain

- Patrick ‘s Faber test [1][22]

- Palpation of the long dorsal SIJ ligament [1][22][35][36]

- Gaenslen’s test [1][22]

- See also SIJ Special Test Cluster

Symphysis :

- Palpation of symphysis[1][22][35]

- Modified trendelenburg’s test of the pelvic girdle [1][22][35]

Functional pelvic test:

- Active straight leg raise test (ASLR test) [1][22][35][36]

Joint examination:[28]

- Spine

- Pelvic girdle

- Hip

- Assessment of the nerves supplying the muscles[28]

- Assessment of functional abilities[28]

Radiological investigations also have an essential role in the evaluation of PGP. Standard anteroposterior, inlet and outlet pelvic films are used to measure the degree of symphyseal separation. PGP syndrome leads to the separation of the symphysis pubis in pregnant women, which result in a higher degree. The use of flamingo can be useful in quantifying the degree of pelvic girdle instability.[22]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Medical therapy for pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy[edit | edit source]

- Intra-articular SIJ injections (under imaging guidance) for ankylosing spondylitis can be recommended. But high quality studies are required for SIJ therapeutic injection therapy.[1]

- Taking simple analgesia (paracetamol)[28]

- Low potency opiates like codeïne and dihydrocodeine[28]

- Avoiding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) during pregnancy[28]

- The use of a pelvic belt has shown to relieve the pain in many patients. Coxal and femur compression deactivated some dorsal hip muscles, reduced vertical SIJ shear forces and increased SIJ compression. This enhanced SIJ stability.[37]

- Acetaminophen in oral or rectal form in cases of mild pelvic pain[15]

- Low-dose aspirin is considered safe during pregnancy[15]

- Cyclobenzaprine, a muscle relaxant[15]

- Opioids may be used on short-term and small dose for severe pain[15]

- Surgery can be performed during pregnancy if the pain is having a disabling, paralysing effect or if neurologic compromise is highly probable, although surgery is considered to have a limited role in PGP.[15]

Medical therapy for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy[edit | edit source]

- Different guiding techniques for intra-articular injections in the SIJ were used either under fluoroscopy or with CT or MRI guidance, this showed immediate pain relief with decreasing effects over time.[1]

- The use of a pelvic belt may reduce mobility/laxity of the SIJ. Effective load transfer through the pelvis, has been improved by the application of a pelvic belt. It has a positive effect on pain and daily activities. A pelvic belt may also be fitted to test for symptomatic relief, but should only be applied for short periods.[1][37]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy for pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy[edit | edit source]

According to the European guidelines of Vleeming et al., exercises are recommended during pregnancy. These exercises should focus on adequate advice concerning activities of daily living and avoid maladaptive movement patterns.[1] It is important to follow an individualized program, focusing specifically on stabilizing exercises for a greater control.

There are not a lot of studies who examined the effects of exercises on pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. These interventions are different with regard to duration and type of the exercises as well as performing individually or in groups. There should be more research for new therapies in the future.[1][38]

Physical therapy for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy[edit | edit source]

After pregnancy, it is also important to focus on specific stabilizing exercises. It has been proven that this type of exercises have a positive effect on pain, functional status and health-related quality of life.[1][15]

The treatment program actually includes several important factors like [35] :

- Advice and education: Informing the patient about body awareness. The purpose of information is mainly to reduce fear and to encourage patients to take an active part in their treatment and/or rehabilitation. General information on PGP needs to be presented (anatomy, biomechanics, motor control) and the patients need to be reassured that their problems are not dangerous to them or their child and that they will probably improve/recover. Ergonomic advice in real life situations can also be helpful, these situations can be really specific like carrying or lifting a child. The patient needs to be encouraged to enjoy physical activity and manage and combine this with periods of rest in order to recuperate.[1]

- Joint mobilization, massage, relaxation and stretching can be executed when indicated. Manipulation or joint mobilization may be used to test for symptomatic relief, but should only be applied for a few treatments. Adjusting asymmetrical motion of the SIJs prior to exercising with joint mobilization may influence optimal form closure and enhance the possibility to exercise without pain. Massage might be helpful, but it must be given as part of a multifactorial individualized treatment program.[20] Manual therapy could be applied even though the evidence is conflicting.[28][39]

- Exercises to retrain motor control and strength of abdominal, spinal, pelvic girdle, hip and pelvic floor muscles.[28] Giving the patients specific stabilizing exercises can reduce pain intensity, lower disability and higher quality of life.[40]

- Pain control: Exercise in water can help.[28] Conflicting evidence shows that acupuncture could relieve pain.[41] Massage and osteo manipulative therapy can also help to reduce pain during pregnancy but further research is required.[42][43] Craniosacral therapy has small pain-relieving effects. If it’s used in combination with standard treatment it diminishes morning pain and gives less deteriorated function. But it’s not recommended for pregnant women since the effect are clinically very small.[44] TENS is a safe way to help patients with pain relief.[45]

The program, for exercise and training, consists of:[15]

- Specific training of the abdominal muscles, which are transversely oriented. This must be performed with co-activation of the lumbar multifidus at the lumbosacral region.

- The following muscles will be trained: Gluteus maximus, latissimus dorsi, blique abdominal muscles, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum and the hip adductors and abductors.

In the initial stage, the treatment program focuses on the training of specific contractions of the deep muscle system, independently from the superficial muscle. The deep muscle system consists of transversus abdominis, obliquus internus, multifidus, pelvic floor and the diaphragm. During all exercises and daily activities they emphasize the importance of activating these muscles before adding the superficial muscles. Depending on clinical findings this focus was combined with information, ergonomic advice, body awareness training, relaxation of global muscles and mobilization.[15][40] Exercises for the superficial muscles were gradually added to the program, when low force contractions of the transversely oriented abdominal muscles were achieved.[40]

The Therapy Master, which is an exercise device, can be utilized to facilitate the exercise progression for most of the exercises.[15][40] In literature, the patients performed these exercises 30 to 60 minutes, 3 days a week, and this for 18 to 20 weeks. They also started with three series of ten repetitions of each exercise.[15] The quality of the execution of the exercise determined the number of exercises and number of repetitions. Each patient received specific stabilizing exercises out of a fixed menu (see photo). The patients may have muscle soreness, but the exercises may not provoke pain at any time. It’s also very important that the patient maintains lumbopelvic control during the performance of these exercises.[15][40] The exercises for enhancing the lumbopelvic control and stability should involve the entire spinal musculature. Focusing on only global muscles seems insufficient.[20]

Patients often have a flare-up of pain when exercising, but this is likely from progressing the exercise load too quickly. This study used an exercise diary so the patient could describe her progression, and seemed to be effective in avoiding flare-ups.[15] It is well documented that exercise supervision is critical for improving quality of exercise performance.[15][40]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Diana Lee, Linda-Joy Lee. The Pelvic Girdle. An integration of Clinical Expertise and Research. 2011(4)

Resources[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)

http://www.womenshealthapta.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pelvic-Girdle-Questionnaire.pdf

http://www.womenshealthapta.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pelvic-Girdle-Questionnaire.pdf

Sacroiliac Joint Special Test Cluster

Long dorsal sacroiliac ligament (LDL) test

Symphysis pain palpation test

FABER Test

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

We can conclude that pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain often is caused by instability of the pelvis or sacroiliac joint. Biomechanical (the wedge shape of the sacrum, the additional compression forces which are generated by the muscles, fascia and ligaments) and hormonal (relaxin, progesterone) factors have an impact on the dynamic stability. These factors can cause an increased motion of the pelvic joints which leads to a stabbing pain deep in the sacral/gluteal region. Patients who suffer from pelvic girdle pain, have difficulty during walking, running, climbing stairs, sexual intercourse and also during sitting and sleeping.

To make the diagnosis of pelvic girdle pain the following tests are recommended for the clinical examination: posterior pelvic pain provocation test , Patrick ‘s Faber test, palpation of the long dorsal SIJ ligament , Gaenslen’s test, palpation of symphysis, modified Trendelenburg’s of the pelvic girdle and the active straight leg raise test (ASLR test). It’s also very important to ask the patient about his pain history.

During and after pregnancy it is important to follow an individualized program, in which stabilization exercises are very important. During this program it is important to focus on adequate advice concerning activities of daily living and to avoid maladaptive movement patterns. The following muscles need to be trained during the exercise program: the abdominal muscles, M. gluteus maximus, M. latissimus dorsi, M. oblique abdominal muscles, M. erector spinae, M. quadrates lumborum end the hip adductors and abductors.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 Vleeming A, Albert HB, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Jun 2008; 17(6) : 794-819.

- ↑ Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec 1;221(6):537-67.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Raizada V, Mittal RK. Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2008 Sep 1;37(3):493-509.

- ↑ Bergstrom et al., Pregnancy-related low back pain and pelvic girdle pain approximately 14 months after pregnancy – pain status, self-rated health and family situation, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 201414:48, DOI: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-48

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JMA, Van Dieën JH, Wuisman PIJM, Östgaard HC. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I : Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. European Spine Journal Nov 2004; 13(7) : 575-589.

- ↑ Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy‐related pelvic pain. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2001 Jun 1;80(6):505-10.

- ↑ Aldabe D, Milosavljevic S, Bussey MD. Is pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain associated with altered kinematic, kinetic and motor control of the pelvis? A systematic review. European Spine Journal. 2012 Sep 1;21(9):1777-87.

- ↑ Homer C, Oats J. Clinical practice guidelines: Pregnancy care. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2018; p. 355–57

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bhardwaj A, Nagandla K. Musculoskeletal symptoms and orthopaedic complications in pregnancy: Pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches and modern management. Postgrad Med J

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: An update. BMC Med 2011;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-15.

- ↑ Damen L, Buyruk HM, Güler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. Pelvic pain during pregnancy is associated with asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2001 Jan 1;80(11):1019-24.

- ↑ Sturesson B, Selvik G, UdÉn A. Movements of the sacroiliac joints. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Spine. 1989 Feb;14(2):162-5.

- ↑ Ritchie JR. Orthopedic considerations during pregnancy. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jun 1;46(2):456-66.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Robinson H.S., Clinical course of pelvic girdle pain postpartum - impact of clinic findings in late pregnancy, Manual therapy 19 (2014) 190-196

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 15.17 Danielle Casagrande et al., Low Back Pain and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy, J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;00:1-11

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 E.H. Verstraete, G. Vanderstraeten, W. Parewijck. Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal: a systematic review. Pubmed 2013; 5(1); 33-43

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Pierce H, Homer CS, Dahlen HG, King J. Pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: listening to Australian women. Nursing research and practice. 2012;2012.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 Elden H., Predictors and consequences of long-term pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: a longitudinal follow-up study,BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016; 17: 276.doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1154-0

- ↑ Ostgaard HC, Andersson GB. Postpartum low-back pain. Spine. 1992 Jan;17(1):53-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Bjelland EK. et al., Hormonal contraception and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy: a population study of 91.721 pregnancies in the norwegian mother and child cohort, Human reproduction. vol 0, No.0 pp1-7, 2013

- ↑ BJELLAND EK et al., Breastfeeding and pelvic girdle pain: a follow up study of 10.603 women 18 months after delivery, BJOG an international journal of obstretics & gyneacology, October 2014, DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.13118 (: 2B)

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: un update. BMC Medicine Feb 2011; 9: 1-15.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Nielsen LL. Clinical findings, pain descriptions and physical complaints reported by women with post-natal pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica 2010: 89; 1187-1191.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Bjelland EK et al., The effect of emotional distress on persistent pelvic girdle pain after delivery: a longitudinal population study, BJOG 2012, DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.12029

- ↑ Owe K.M. et al. How does pre-pregnancy exercise influence the risk of pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy? 2015 Oslo university Hospital.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Morgen, IM. et al; Low Back Pain and Pelvic Pain During Pregnancy: Prevalence and Risk Factors; Spine; 2005 April; pp 983-991

- ↑ Morino M, Pellegrino L, Castagna E, Farinella E, Mao P. Acute nonspecific abdominal pain: A randomized, controlled trial comparing early laparoscopy versus clinical observation. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):881–888. (: 2A)

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 Pelvic Obstretic & Gyneacological Physiotherapy. Guidance for health professionals, pregnancy- related pelvic girdle pain.

- ↑ O’Sullivan PB et al., Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework, Man Ther. 2007 May;12(2):86-97. (Level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Stuber KJ. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2007;51:30-41.

- ↑ Hanne Albert et al., Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain, Eur Spine J (2000) 9 : 161–166.

- ↑ Stuge. B., The pelvic girdle questionnaire: a condition-specific instrument for assessing activity limitations and symptoms in people with pelvic girdle pain. phys ther 2011; 91:1096-1108

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Evensen M.N. et al. Art1: Reliability of the timed up and go test and ten-metre timed walk test in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain, , Physiotherapy Research International 20(3), December 2014, DOI: 10.1002./pri.1609

- ↑ Sturesson et al; Pain pattern in pregnancy and" catching" of the leg in pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain; Spine; 1997; PP 1880-1883

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vollestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Spine Feb 2004 : 29(4) ; 351-359.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Vollestad NK, Stuge B. Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal Feb 2009: 18; 718-726.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Pel J.J et al., Biomechanical model study of pelvic belt influence on muscle and ligament forces, J Biomech. 2008;41(9):1878-84.

- ↑ Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N. Physical therapy for pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2003: 82; 983-990.

- ↑ Hall H. et al., The effectiveness of complementary manual therapies for pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Sep; 95(38): e4723.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 Mens JM, Pool- Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ. Mobility of the pelvic joints in pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain : a systematic review. Obstetrical Gynecological Survey Mar 2009; 64(3) : 200-208. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Kaj Wedenberg et al; A prospective randomized study comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy for low‐back and pelvic pain in pregnancy; AOGS; 2000 May; 331-335

- ↑ Helen Hall et al., The effectiveness of complementary manual therapies for pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain, Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Sep; 95(38): e4723.

- ↑ Pennick V. et al., Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy (Review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 1;(8):CD001139.

- ↑ Elden H. et al., Effects of craniosacral therapy as adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: a multicenter, single blind, randomized controlled trial, ELDEN H. et al., Januari 2013 AOGS, DOI: 10.1111/aogs.12096

- ↑ Qiuttan M. et al.,Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve stimulation (TENS) in patients with pregnancy- induced low back pain and/ or pelvic girdle pain, phys. med rehab kuror 2016:26: 91-95. ISSN 0940-6689